The first and most important lesson was cooperation between the army and navy. This was achieved by clearly stating the limits of responsibility of each party. Obviously, the Navy's part was to transport the Army safely to the landing place. The choice of the landing place was jointly made through consultation by both army and navy commanders. The Navy then landed the soldiers and its responsibility ended when the men were out of the boats.

Personal relationships could cause problems, but in all of our examples, cooperation was good. Major General Jeffrey Amherst and Admiral Boscawen cooperated fully at Louisbourg. Wolfe depended entirely upon Admiral Saunders to bring about his plans at Quebec. During the recapture of St. Johns, Lieutenant Colonial William Amherst (Jeffrey's youngest brother) was at great pains to foster good relations with Admiral Lord Colville, for his brother had written to him saying, "I must recommend that you preserve the greatest harmony with the Navy..." while similarly writing to Lord Colville as well.

The navy conferred great strategic and tactical flexibility on the army and supported it with great confidence. The Navy was prepared to convoy troops to Halifax even though at one point naval supremacy was not assured. Whilst giving minimum protection to the transports, the warships concentrated to prevent the movement of reinforcements to Louisbourg from France. Tactical flexibility was very important too. Bad weather at Louisbourg forced several changes of plan, all of which the Navy accommodated.

In the St. Lawrence, the Navy carried out several operations large and small. They landed Rangers on the isle of Orleans to scout the island before the main force landed. Later Wolfe was able to keep the French guessing as to where the main attack would come by strategems of ship movements. The movement up the St. Lawrence past Quebec and then immediately back at night to the landing place of the Anse de Foulon was entirely the responsibility of the Navy. Stores and equipment were kept on store-ships until needed thus protecting and preserving them. At St. Johns, this flexibility was exploited fully. The troops landed in light order north of the port and drove the French defenders back overland. Heavy equipment and stores came round by local boats called "shallops" to support the infantry. Amherst wrote of this, "Twenty-nine shallops are coming in with artillery, stores, camp equipage, provisions, etc. We land them as fast as they come in."

The crucial point in any amphibious operation was the actual landing of the troops on the beaches. This was a very risky business especially if the weather was bad or the beaches contested by the enemy. The risk had to be minimized by caref ul preparation and planning.

As much information was collected as possible. The British knew a great deal about Louisbourg and St. Johns from their previous occupations and quite a bit about Quebec. St. Johns was of course a British possession. This was supplemented by as many means as possible. Amherst and Brigadiers Lawrence and Wolfe made personal reconnaissances of the Louisbourg beaches in small boats and other boats were sent to provoke defensive fire to reveal the French positions, while William Amherst discovered the size of the French force at St. Johns by interrogating a deserter.

Once the plan had been decided an experienced naval officer was picked to organize the landing itself. At Quebec Captain James Chads was chosen for this role. It was the practice to issue detailed orders and to explain the operation to subordinates beforehand as Boscawen did at Louisbourg. The latter gave them strict charges to be diligent in the execution of these orders."

Before leaving Halifax the Louisbourg force, "Made an experiment [of] how many men could be landed conveniently at the same time from the transports." 2,957 men were landed and formed up in seven minutes from leaving the boats. Boscawen recorded two such exercises in his 'Journal'. This kind of practice was not at all common but shows the new approach to amphibious warfare adopted from 1758 onwards. An additional advantage was gained in that the Louisbourg force put its learned experience into effect the next year at Quebec.

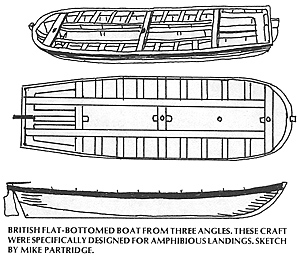

Another demonstration to the serious approach was the use of specially designed landing boats. They were called flat-bottomed boats or flats and were designed only for amphibious operations following the Rochefort failure. There were two sizes; 30 or 36 feet long, were fully capable of being carried on transport ships so that they could be lowered to sixty soldiers and rowed to shore by 16 to 20 sailors commanded by a petty officer or junior officer. The soldiers were seated in such a way that they could leave the boat over the bows and form up in ranks ashore as fast as possible.

BRITISH FLAT-BOTTOMED BOAT FROM THREE ANGLES. THESE CRAFT WERE SPECIFICALLY DESIGNED FOR AMPHIBIOUS LANDINGS. SKETCH BY MIKE PARTRIDGE.

BRITISH FLAT-BOTTOMED BOAT FROM THREE ANGLES. THESE CRAFT WERE SPECIFICALLY DESIGNED FOR AMPHIBIOUS LANDINGS. SKETCH BY MIKE PARTRIDGE.

Once the boats were loaded, they formed up by units resembling the Army's order of battle, first in echelon and then in lines within the echelon. Each boat was numbered and carried a flag to indicate the unit it carried. Sub-divisions of the attacking force had their own flag. At Louisbourg, Wolfe's boat had a red flag, Brigadier Whitmore's was white and Brigadier Lawrence's was blue. in fact, a complex system of signals was used to control operations at Louisbourg including flags, lights and cannon shots. This coupled with the position of the Brigadiers with the leading flat boats enabled control to be exercised so that several changes of plan could be accommodated. This flexibility turned the assault landing from being a defeat into a victory when the troops were directed to land at a spot sheltered from enemy fire. Even at Torbay near St. Johns, William Amherst directed the landing of a few hundred men with flags.

Getting soldiers onto the beach in enough numbers was vital and most commanders did not have enough flat-bottomed boats. For example, Wolfe complained of having only thirty in 1759. It was therefore usual to supplement the flats with as many other ships' boats as possible. At St. Johns local fishing boats (shallops) were used.

At Louisbourg, Quebec and St. Johns the assaults were made in the early hours of the morning. This is a measure of the confidence that the commanders had in the Navy's ability to organize complicated arrangements in the dark. Night assaults were rare in land operations.

Elite soldiers such as grenadiers or light troops were usually the first to land. At Louisbourg, Wolfe's assault consisted of Highlanders and Rangers. The supporting echelons had to be put on the beach as soon as possible. The failure to reinforce the first echelon to land was a reason for the failure of the Rochefort expedition of 1757. The boats landed their troops and then quickly returned to pick up more men from the transports who usually flew flags to indicate that they had troops still to be unloaded. In this way, all the force was landed at Louisbourg by 6 a.m., two hours after the attack had begun.

While the boats were assembling in formation, warships were "scowing" the beach defenses to suppress enemy fire. A bomb ketch and a frigate fired on the considerable French defenses at the Anse de la Cormandiere in Cabrus Bay west of Louisbourg. Other ships fired at other targets to create a diversion and confuse the French. This firing lasted fifteen minutes and does not seem to have made much impression on the defenses since later defensive fire was so fierce that the operation was nearly called off.

The landing succeeded only because another landing place was found. it was shielded from enemy view and enabled the troops to land and take the French in flank. Similar suppressing fire failed to help British grenadiers landing a year later near Quebec at Montmorency Falls (July 31, 1759). This landing was a bloody failure and demonstrated what could go wrong in a landing. A few months later the landing at the Anse de Foulon depended on surprise and a bombardment was out of the question except for a diversionary bombardment of Beauport by Admiral Saunders.

The soldiers sat in the boats with their loaded muskets between their knees in their pre-arranged ranks. Firing from the boats was forbidden and bayonets were only fixed after landing. For embarking and disembarking, muskets were slung muzzle uppermost and sometimes had their locks wrapped in cloth or leather to keep water out. It was considered very important that the boats should row straight to the landing beach in a determined manner ignoring enemy fire. The troops carried a fair amount of ammunition of 60-70 rounds plus basic rations. At Louisbourg, by Boscawen's orders they landed "...with bread and cheese in their pockets for two days."

In his advice and orders to his brother William, Major General Jeffrey Amherst had these interesting things to say on August 13, 1762. "You know my opinion of men being in their waistcoats for active service. A blanket rolled up is not an encumbrance, is all they want, and two or three day's provisions ready dress'd is a necessary precaution. 'Tis time enough when well posted, to send for tents, etc."

After Landing

As soon as the troops landed, they were to form up in their normal manner with the grenadiers and light infantry securing the flanks. In this way even small bodies of formed troops could beat off counterattacks as at Louisbourg and on a much larger scale on the Heights of Abraham the following year. Boscawen's orders of May 21, 1758 makes this clear. "As fast as the men get out of the boats, they must form and march directly forward to clear the beach and charge whatever is before them: they are not to pursue but will be ordered to take post, so as to effectually secure the rest of the Army."

William Amherst's own orders reflect the value of light infantry in these operations when he wrote, "The light infantry will immediately seize the most commanding ground, so as to cover the landing of the remaining troops, who will form as soon as they land... The light infantry... will arrive to get upon [the enemy's) flanks, will cut off their retreat if possible, in which they shall be supported by the [battalions), but the light infantry must not pursue out of the reach of the support from the battalions. Upon the march, the light infantry will cover the flanks of the line, seizing every commanding ground till the line has passed; wherever they may chance to fall in with the enemy they will stand their ground, and never retire to the battalions, which shall always march up and support them."

This is a classic description of the use of light infantry and shows how much the British Army had learned by 1762. Incidentally, the light infantry consisted of two companies of "recovered men" from the West Indian campaigns made up from seventeen separate regiments plus the light infantry of Hoar's Massachusetts provincials.

To support the infantry, artillery could be landed using the flat- bottomed boats. The guns were the usual lights pounder battalion guns in the three landings with which we are concerned. At Louisbourg, bad weather prevented landing artillery until three days after the assault. They were more use at the Heights of Abraham where two 6 pounders supported the line, They were not too important at St. Johns although two were positioned a day after the assault to defend the beach head and to support the advanced troops.

All three of the operations were meant to capture strongpoints. At Louisbourg and St. Johns the landings were followed by sieges; one lengthy - the other of three days. At Quebec, the pitched battle on the Heights of Abraham following the landing brought about capitulation of the city. All were part of the plan to seize French colonies in North America. With hindsight, this success seems inevitable although it was not really the case at the time. A failure before Louisbourg or Quebec would have had far-reaching consequences. Success was achieved largely due to the expertise and skill shown in the amphibious operations.

British Amphibious Operations in North America 1758-1762.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 2

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com