The Vickysburg campaign was conceived in the wake of the Relief of Frumpburg. The map moving system would be the same, the Charles Grant system, with extras, supply and naval movement, added. We adopted rules for reinforcements and the return of casualties. The tactical rules used were IRONCLAD by Tom Wham, and an otherwise unpublished set of ground tactical rules. The map was designed in a couple of evenings and was originally kept rolled up by one gamer. Later we mounted it on cardboard and took turns storing it so each player could benefit from studying it. Only one map was made, in contrast to the campaign to relieve Frumpburg where photocopies were made of the map.

As in the Relief of Frumpburg, the weather system was taken from SPI's game COBRA (see Table 1). Modifiers were put in to allow for seasonal adjustment. That the weather during the campaign was excreable was not the fault of the table, but rather the ability of one person to consistently generate bad weather with every die throw (this skill manifested itself in other campaign games, too; the inevitable result being that he was never again allowed to throw a weather die).

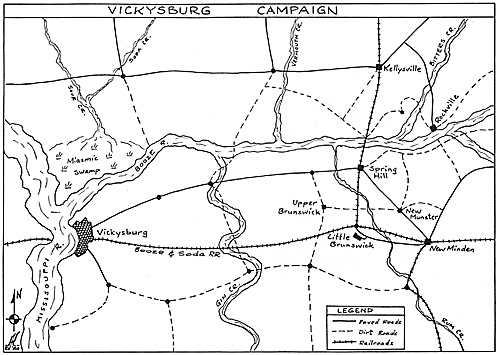

The forces involved were taken from BATTLES AND LEADERS OF THE CIVIL WAR, each side settling on an order of Battle from a specific engagement. The Confederate commander (General Shortstreet) took his from Antietam. The Union commander (General Charles Mopps) took his from Shiloh. A schedule of reinforcements amounting to an average of 20% per month was worked out, bases were designated, Vickysburg and Cincynooti, and advanced bases were occupied, the Confederates at New Minden and the Federals at Kellysville.

Players were asked to keep a log of orders issued, including orders received from far away War Departments. Regimental returns were prepared, and forwarded, with the Union player keeping track of'Present for Duty, Equipped'as a separate category from'Present for Duty', and the Confederate player simply listing 'Effectives'. in some cases regimental reports were prepared following actions, and the whole campaign was given a personal touch by adding letters from private soldiers, "articles" that appeared in future Battles and Leaders, and so forth. (Looking back, these extras, though they did not effect the campaign one whit, were worth the trouble. They made it seem like a real campaign, not a game with model soldiers.),

The supply rules governed the campaign across the Booze River. A single man was assumed, upon leaving base (and if it had railroad connections), with 8 days of hardtack and other rations. Both sides drove cattle along with the troops at a rate of 2 head per company per week. Supplies were scrounged from the countryside within 1" of the halting place for the night (marching in small, separate columns was a necessity as there was no food where food had been scounged - alternatively a unit could spend less time marching, and scrounge up to 1" more from the road for each turn they didn't move). Farm land could provide for 2,000 mouths (1 man = 1 mouth; 1 horse = 10 mouths; 1 head of cattle = 15 mouths; 1 mule = 8 mouths). A town or village could equal that. A wagon could carry 2,000 rations for men. A railroad could run 6 trains a day (a low assumption) on single-track, and a standard train of 20 cars carried 10 cars of food and 10 of ammunition. A railroad car carried 10 wagons of rations.

Simple as they were, these supply rules effectively tied us to the railroad except for short periods. Doing several calculations, it was determined that a division could spend 1 week away from the railroad before eating itself out, provided it did a reasonable amount of marching. If if took supply wagons with it, it would have to be more careful, the animals pulling the wagon eating, too. After a couple of trials it was found that it was better to let the animals eat up the countryside and carry rations for the men in the wagons. An army that stopped had to spread itself out for supply reasons. A prolonged siege of the fortifications of either Cincynooti or Vickysburg would require open communications for the attacking force in order to live, and even then the countryside would be eaten bare in short order.

The first clash of the campaign was a staged action at Kellysville. The reason for it, officially, was a reconnaissance in force by the Confederates. The other reason was to give the tactical rules a final check, it was a closely fought battle, and the Confederate forces were beaten back after a prolonged, desperate, and bloody fight. General Shortstreet developed a healthy respect for Union artillery, especially the regulars, and General Mopps discovered that volunteers did not maneuver like regulars.

Table 3 - Vickysburg Campaign Forces

Union - General Mopps

- 1st Division - 6200

2nd Division - 7150

3rd Division - 6500

1st Cav Bde - 1500

2nd Cav Bde - 1400

Res Arty - 1050

L of C trps - 1800

Total - 25,600

4 gunboats, 2 rams

Confederate - General Shortstreet

- 1st Division - 5500

2nd Division - 6100

3rd Division - 7000

1st Cav Bde - 1200

2nd Cav Bde - 1400

3rd Cav Bde - 1700

4th Cav 13de - 1100

Res Artillery - 1100

*4th Division - 6450

Total - 31,550

4 gunboats, 2 steamers

* Garrison of Vickysburg

Both sides spent the winter bringing up reinforcements, building supply dumps, and making plans for the spring campaign. General Shortstreet confidently expected his opponent to thrust south of the Booze River. He decided to hold most of his troops there. He had 4 gunboats, and he planned that they, escorting 2 steamers, would wait until the Union forces moved south of the Booze, and then move north and demolish the railroad bridge at Cincynooti. The steamers would put ashore2 regiments of Confederate cavalry and a regiment of infantry to harass the Union lines of supply. Such a force, he calculated, would tie down more troops than he committed, and allow him to crush any Union forces rash enough to cross to his side of the river.

General Mopps originally decided to thrust directly at Vickysburg. But a careful consideration of the supply situation, plus information about the Confederate gunboats, quickly ruled this out. The Union army could force a crossing of the Booze River, only to starve about the time it got to Vickysburg. Reluctantly he decided upon another plan of campaign. He would try to defeat the Confederate force, secure an area on the south side of the Booze River so he could extend the railroad, and then march on Vickysburg. After a little more thinking, and a careful calculation of river supply (11 steamer = 5 railroad cars), he decided to try to cut off the Confederate supplies, and then force it to battle. With his forces spread out so they could eat they would be easy pickings for the Union army.

New Minden was the obvious target. if he could get the Confederates out of the way he could move there. By loading every wagon with fodder rather than hardtack he wouldn't have to spend time looking for food. He could reach New Minden, barely, but only if he didn't take everyone with him. The cavalry, especially, would have to be dispensed with, or more profitably, sent on a raid to confuse things. And to get the Confederates out of the way he assigned his latest arriving artillery, and the mounted infantry, plus a brigade of volunteer infantry, to thrust across the Booze River at Spring Hill. By sending his pontoon trains with them he could make it look like a major thrust. The bulk of his command would cross upstream of Rockville, wading one of the fords reported there. He would keep one regiment of cavalry with the main body as a screen, and spring the rest loose on a raid.

The Confederate plan could be faulted for leaving the initiative to the Union forces, but General Shortstreet was planning on using all of his forces for whatever he did, excepting the raid dispatched to tear up the rear of the Union forces. The Union plan had several weaknesses: what if the fords were impassable? what if the Confederates conducted a vigorous series of probes with his cavalry? what if he didn't move out of the way in response to the deception at Spring Hill? The virtue of the Union plan was that it would be unexpected, and, if worst came to worst, would produce a battle south of the Booze River with the latter as a barrier in case of defeat.

Campaign Start

The start of the campaign was officially March 1st. By agreement of both sides the day before was considered fair. The weather was thrown for, came up bad, as it was to continue for the rest of the week. The two sides, though, proceeded on their respective schemes. The Confederate gunboats sailed upstream, convoying the steamers, the Union force destined for Spring Hill left with great fanfare, and the other Union force moved slightly north to get the benefit of various roads converging on Rockville.

Dawn of the 2nd saw Union artillery in action covering the troops crossing at Spring Hill. Vigorous skirmishing broke out, the Union troops pushing south aggressively. For several days, 3 in fact, they would mesmerize General Shortstreet. He took one look at the options open to a force at Spring Hill, saw their proximity to his railroad lifeline, and ordered his divisions to march to Spring Hill. He left 1 regiment of cavalry at New Minden, and sent another to picket the fords upstream of Rockville.

The main Union force got across the Booze at Rockville in the late afternoon and night of March 2nd, except for the wagons and cattle, who crossed on the 3rd. The Union cavalry did not stop aftercrossing, but force marched south and then west, striking for the Booze and Soda RR.

March 3rd saw the Union cavalry run into the Confederate regiment that had been sent to picket the river. A running fight sputtered back and forth across the roads toward the railroad as the Confederates did their best to hinder the Union cavalry. As a result there was a hole in the Confederate cavalry screen, something that was not noticed by either general until after the fighting was over. And through this hole marched General Mopps, 21,000 Union infantry, 600 cavalry, and 60 wagons of fodder.

Elsewhere, there was a brief cavalry clash at Spring Hill. Artillery fire served to beat back the Confederates, but not before they identified the pontoon bridges and formed infantry deployed for battle.

March 4th saw the arrival of General Shortstreet's main body at Spring Hill. They had averaged 19 miles a day through the rain, moving on the only macadernized road in the area. They were hungry, and General Shortstreet put 1 division in line, and spread the rest out so they could forage. He planned tos pend the day probing the Union position, followed by aclawn attack on the 5th. That night numerous campfires were spotted lighting the sky north of Spring Hill.

General Mopps and his infantry toiled through the muck of the "dirt" roads toward New Minden. The cavalry splashed (literally) ahead to make contact with the garrison of New Minden. The latter saw them off rather easily. (General Shortstreet later confided that this convinced him that this was just part of the cavalry raid taking place farther west at this time. He gave the orders necessary to stop drawing supplies from New Minden, gathering food, instead, from forage and the constant shuttle of railroad trains from Vickysburg.)

The cavalry raid was attracting Confederate cavalry. The commander of the raid, General Chivington, tried hard to reach his objective, but had to stop repeatedly to fight with small forces of Confederate cavalry. it cost precious time. At nightfall he was still short of the Booze and Soda RR.

March 5th was a repeat of the 4th, except that Chivington's command got to the railroad. But pressure from Confederate cavalry kept them from doing much damage to the tracks. As there was a bridge at Little Brunswick, Chivington decided to burn that, and then withdraw toward New Minden. He had one satisfaction, and that was 3 brigades of Confederate cavalry were chasing him. This kept them from doing other things, such as finding the Union main body.

General Shortstreet's proposed Battle of Spring Hill never came off. The only approaches to the Union position were visibly fortified and well stocked with Union guns. He let his forces get into a prolonged artillery duel to convince himself that the guns were real, not painted logs. Only after the campaign was over did he find that they were painted logs (in several positions) for the most part, and the heavy Union fire was from 3 batteries of artillery that had most of the army's reserve artillery ammunition with them.

The main event of the day took place near Cincynooti. The Confederate gunboats, helping the steamers move into land the troops at Singer's Ferry,were surprised by the Union gunboats recentlyarrived at Cincynooti. A spirited and confused naval action took place, the Union flotilla being driven off with 2 of its 4 gunboats and I of its 2 rams sunk. The Confederates lost 1 sunk, 1 disabled and drifting downstream, badly shot up. The Confederate cavalry landed at the height of the battle and proceeded inland. Only after the fighting was over were they joined by the infantry regiment.

At Knicksville this force ran into a garrison of 9 month volunteers and a mountain battery. A very low key skirmish broke out, the Confederates trying to get into Knicksville, and the Union force hoping someonewould show up to rescue them. The obvious tactic of simply rushing the place was rejected by the Confederate commander, who recalled the skill of Union gunners already displayed in the campaign. Night fell with no result save for a few casualties.

On March 6th the Confederate gunboat that had survived the battle moved to Cincynooti, but was quickly driven off by a battery of smoothbore 32#'s dug in along the waterfront. To get at the bridge they would have to pass the battery, beat off the Union gunboats that were known to be around, and spend several turns in the close vicinity of the bridge with no guarantee of success. After 2 shots pierced the hull below the waterline discretion was opted for, and they fell back downstream to wait for the cavalry to come up.

That force, however, was still trying to do something about the Union force in Knicksville. After trying to get north of the town without being shot at by the artillery, the Confederate commander decided to rush the place. The night allowed the Union defenders had resulted in numerous barricades, and their Springfield rifles did the rest. The Confederate cavalry fell back on their infantry, and the whole force retreated to the river, expecting troops that had to be arriving from Cincynooti to intervene. (They had no way of knowing that the troops in Cincynooti were mostly concerned with the threat posed by a Confederate gunboat, and that the garrison of Knicksville had been written off.)

South of the Booze River General Shortstreet was beginning to smell a rat. The force in front of Spring Hill probed constantly, but never seemed to amount to much. He worked a couple of regiments of infantry forward as a probe, and they got shot at vigorously by artillery and infantry. He knew there were Union troops there, but he couldn't seem to tell how many. He knew the Union army was big enough that if it was seeking a battle it would have done something by now.

Behind his position the Union cavalry raid was getting in deeper and deeper trouble. The attempt to burn the bridge at Little Brunswick failed due to the rain and attacks from Confederate cavalry (and atrocious die throwing). A regular battle see-sawed across the bridge, the Union force finally retreating in the darkness. They made a forced march, men dropping from fatigue (attrition from not resting for 8 hours during the day). A fresh Confederate force stood waiting for them at Upper Brunswick, and this proved to be a rude surprise for Colonel Chivington the next morning.

The main body of the Union army had planned on being in New Minden by now, but the rain had slowed everything up. They had enough rations to make the town, assuming it continued to rain (it did), and the wagons were left behind. Since they moved at quarter speed in the mud General Mopps left them with a division of infantry. The latter swung off with all of General Mopps' artillery to occupy the ridge at New Munster. This was the only direct route between Spring Hill and the road the Union army was using, and General Mopps thought it a precaution worth taking (he also liked the idea that they could forage in the area and relieve some of his supply worries).

The main body of the Union army had planned on being in New Minden by now, but the rain had slowed everything up. They had enough rations to make the town, assuming it continued to rain (it did), and the wagons were left behind. Since they moved at quarter speed in the mud General Mopps left them with a division of infantry. The latter swung off with all of General Mopps' artillery to occupy the ridge at New Munster. This was the only direct route between Spring Hill and the road the Union army was using, and General Mopps thought it a precaution worth taking (he also liked the idea that they could forage in the area and relieve some of his supply worries).

March 7th was the day the veil was torn from General Shortstreet's eyes. The telegraph operator at New Minden reported the presence of Union infantry, and then fell silent. Another telegraph operator, farther down the line, filled in the details from the retreating garrison (for the gamers it went this way: Union player - G3, "At New Minden, contact unless you moved out." Confederate player - "No, I didn't. I've got 600 cavalry there, what do you have?" Union player - "14,000 infantry and 200 cavalry! Want to game it out?" Confederate player (realizing the dimension of his strategic error) -"Damn it, you bamboozled me! Okay, my guys are cutting and running. That badly outnumbered they wouldn't have time to stop and burn the warehouses or bridge. I'm cutting the telegraph line, though." Union player - "Thought so. Ready for the next call?").

Colonel Chivington split up his force in an attempt to get away. Four Confederate cavalry brigades, and a brigade of infantry, spent most of the day hunting down the Union troopers. Colonel Chivington was one of the casualties as he and 2 companies tried to cover the flight of the rest.

On turn 3 ot the day General Shortstreet gave orders starting all of his forces except 1 brigade and 1 battery to march directly on New Minden. This was a forced march along the macadam road. His troops would move rapidly despite the weather, but they would be strung out in order of march and would take several hours to concentrate for battle. Only part of the ground had been foraged over a few days previously, so supply would not be a problem. He planned on spending the night about 9 miles short of New Munster, and then moving directly on New Minden, confident that some of the Union forces present would be scattered around, moving slowly due to the mud. And they would have no cavalry out scouting. Most of that had been dispersed.

Farther north the Confederates were surprised while embarking their cavalry and infantry. A Union gunboat, escorting a ram, appeared around the bend while the Confederates were busy. While the Confederate gunboat was engaged, the ram attacked one of the steamers. The damage was heavy, but not fatal, and the ram was blown apart by the badly damaged, but still functional gunboat that had also survived the battle a few days before. Frustrated, the Union forces retreated to Cincynooti,

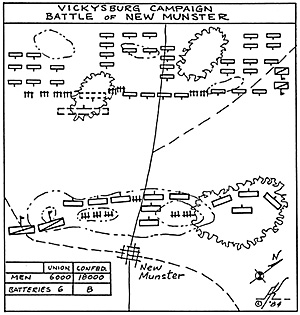

The Union division at New Munster had spent the morning of March 8th building rudimentary defenses. At noon he became aware that the Confederates were arriving in force in front of his position. General Shortstreet launched a pinning attack with the lead division of his army, and waited impatiently for the othertwo. A long range artillery duel, and a prolonged skirmisher fight, rattled through the damp afternoon while the Confederates deployed. They had 18,000 men to the Union's 6,000 men, but the Union artillery was just as numerous, and it was better sited. With little more than an hour of daylight left the Confederates rolled forward in an attack. A very hot and very bitter fight broke out, highlighted by the inability of General Shortstreet to coordinate his units (bad die-throwing on the command and control), and a heavy concentration of artillery fire that silenced the Confederate artillery from time to time.

Despite the lack of coordination the Confederate attacks stretched the Union troops to the limit. All Union reserves were committed, and every man was in the line with the exception of the surgeons and the general commanding (and he had his pistol out- he was, after all, the only mobile reserve on the Union side at the moment). The Confederates finally gained the ridge by outflanking the Union position, and then chance took a hand. General Shortstreet's horse was hit and he was temporarily out of action (1 turn). It was a critical delay, and there was no one to provide the final push that would have turned the Union defeat into a smashing rout. In good order, but severely shaken, the Union troops fell back far enough to find themselves entangled with the cattle and provision wagons still toiling through the muck.

After dark, assessing the situation, General Shortstreet was disturbed to receive reports that a strong force of all arms had left New Minden during the afternoon. A night march, he decided, would take them either to Little Brunswick, or could bring them into a position on his flank. In either case he was not in the proper place. He gave orders to load the wounded on what wagons could be found, and to fall back to Little Brunswick.

At this point the campaign was effectively over. Little over a week, for the troops, had gone by, but close to 3 months of player time had expired. We had gamed twice a week, usually for 4-6 hours each time. At one point we each had more than 40 separate forces scattered across the map. It took time to resolve the contacts that grew into fights. The running cavalry engagement of Colonel Chivington's column, for instance, took nearly 3 weeks to resolve. The fight at Knicksville took most of three evenings, not counting the naval engagements, which took another evening. The faking at Spring Hill was set down only once, and that took a full evening. All in all we were taking close to 2 weeks, at the height of the campaign, to resolve 1 day. The system worked, but the forces were getting out of hand. And yet they were not really any larger than what we had deployed to relieve Frumpburg.

Soured

We had thought that the supply would be the hardest part. It turned out to be the easiest after we sat down and did some calculations. What soured it for us was all of the little contacts. Most of them could be resolved by a brief discussion, but when a cavalry raid ran into trouble, or something unusual happened, we often had to set itouton thetableand game it.This led to certain problems with bookkeeping. Any campaign game will have numerous contacts, but in the Grant system you have to check records to find out how many inches, and fractions of an inch, a unit is away from someother place. If it is within the rectangle,and henceon the table,you have no problem, but for something like a tip and run raid on a column or march, or cleaning up scattered raiders, the problem becomes nearly impossible. This, however, is something that would be inherent in any campaigning system.

Compared to the Relief of Frumpburg, the Vickysburg campaign was complex. There was a lot more going on, a pair of naval engagements, a ship to shore bombardment, a reasonably large battle, a wide strategic maneuver, a pair of cavalry raids, and so forth. Perhaps it was too complex, but a system should be able to encompass what would be tried in the real world if it is to be of any use. Whether the machanics accurately reflect what you are trying to accomplish is always a problem, and in the Charles Grant system both sides felt that the mechanics sometimes got in the way.

Of course the strong part of the system is that you can do so many different things without adding artificial rules. Any map can be used, whether it is a highway map of some state or something made up one night while emptying beer bottles, and making up a map has a certain bit of fun to it. Very few other campaigning systems require such little preparation of the map. Most have to have something laid down to assist movement, such as a hex grid. in the Charles Grant system you lay out the grid for determining the battlefields, and off you go.

Bookkeeping, as mentioned before, is the crux of any system. The morning of March 7th was the critical day during the campaign, and it was the day that took the longest to work out. Confederate cavalry units were converging from all directions on Chivington's raiders, and in the final fight not a single tactical turn went by without more Confederates arriving. This was something that we could do only because we worked out how many fractions of an inch from their starting places, or certain known landmarks such as towns, a unit was. But we spent nearly 1/3rd of our gaming sessions on 1 day of the campaign. It made for exciting gaming, and it was fun, but in retrospect there had to be a better way to do it. The Grant system couldn't quite stretch to do it.

The system did work. it has a lot of merits, but it can be unwieldy and time-consuming, especially for a small number of gamers. The battles we produced were not the typical ones normally found in one-off games, and we all could see what was at stake in the battles beyond the immediate tactical objectives. While we enjoyed the campaigning, the consensus was to choose another system for the next campaign.

More Campaigns

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1986 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com