Although we tend to think of the late 19th Century French Army in terms of Republic and Empire, in many respects it received its distinctive style and appearance from the reign of Louis Phillip, the "Citizen King". During his monarchy from 1830 to 1848 the tricorn returned. The army went to Africa and acquired zouaves, tirailleurs indigines who would be come Turcos, La Legion Etrangere, and the superb chasseurs a cheval d'Afrique who would distinguish themselves in the Crimea, Mexico, and in the chevauchee la morte of Sedan. Even the red robed Spahis were formed in Africa in 1834 and numbered three regiments by the time Napoleon III became "President for Life".

Thorburn (French Army Regimentsand Uniforms) shows a print of a light infantryman in Africa, 1841. He wears a red "casquette d'Afrique" trimmed blue. Hiscoat isthe double breasted blue greycapote with black belting. His dark red "pantalon rouge" ends in white or tan leggings. Of course, he holds a flintlock musket in place of a Minie, Chassepot, or Lebel. Other differences were to be found. The epaulettes at that time marked him as a member of an elite company -- presumably a carabinier, since they wore red and he is after all a light infantryman. Center companies as yet has no epaulettes -- at least according to regulation. The center companies of light infantry, or chasseurs, had a blue shoulder flap trimmed yellow, with yellow collar. Those of the line infantry had red trim on the shoulder flap - same on the old coat, which looked rather like those of Napoleon I. The tunic was introduced in the 1840-42 period. Epaulettes of red for grenadiers and carabiniers remained in vogue, with yellow epaulettes with green crescent for voltigeurs. They could be worn with the tunic or the capote.

In 1841 the dress shako had a slight taper at the top. Under Louis Phillip it would go through several changes. In 1844 it had a bomb (line) or horn (light) of brass on the center front, and a brass cockade at the top where the plume could be attached. The full color collar became a collar patch in the mid 1840's. Also, the light infantry buttons were white metal and those of the line of yellow metal.

In the army Napoleon III acquired from monarchy and brief Republic, there were 75 line and 25 light infantry regiments, and 10 battalions of Chasseurs d'Orleans. Each battalion had 8 companies, 6 of fusiliers or chasseurs, plus the two flank companies already discussed. The light infantry were descended from the original chasseur battalions of the revolutionary armies. Throughout the first empire these became regiments of multiple battalions, increasingly like the line infantry in function. The chasseur battalions named after their patron, the Duke of Orleans, were once again true light infantry, like the Prussian jagers or British rifles. Only in 1867, when the Chassepot became general issue, did the line infantry have as good a weapon -- but more of that later.

In 1852 the fusiliers received a green fringed epaulette with red crescent, and the shako received an eagle to which a crown was added. The black leather chin strap also became brass scaled. The capote lost its collar and cuff colors except for the small collar patch and the line tunic received a yellow collar. The common field uniform retained the shako, or used the "bonnet de police a visere" or "casquette d'Afrique" in a shortened form, still trimmed blue. Shakoes were black with a band at the top and narrow vertical stripes on the side of dark red for the line, yellow for light infantry. It was worn in the field by the expeditionary force to Rome in 1849 usually with the black cloth cover and a yellow or red regimental number in front. The blue-gray overcoat, red pantaloons, and off-white gaiters completed the ensemble.

By now the line and light infantry carried the percussion musket, while the light infantry (in the true sense, the chasseurs d'Orleans, with steel gray trousers and yellow stripe habitually wearing the single breasted tunic in the field instead of the capote) carried a cap and ball rifle. The carabinier companies carried a heavier and more powerful sniper style weapon (also cap and ball).

The Crimean expedition of 1854 was undertaken generally in the capote and kepi. However, regulations did not require this, so certain regiments started out with the shako, including the 7th and 27th line. An order of 20 March 1854 mandated the kepi only for use in the field. On 24 October 1854 the light infantry was recognized to be in fact line infantry and became the 76th to 100th line regiments. Light infantry duty fell to the chasseurs and the voltigeur companies. Up to 114 battalions were involved. The kepi remained red with dark blue band and stripes. Due to the cold weather an emergency issue was made of an overcoat with a cape-like hood. These came in dark blue, blue-gray, and even dark gray. A grenadier is depicted with dark red grenades on the corners of a turned down hood. This garment, which tended to be somewhat darker than most issues of the capote, was known as the "Crimean". Basically it looks like a regulation U.S. Army ACW overcoat. It was often worn without the epaulettes. This means, of course, that you can use any U.S. Army (Federal) figure of the ACW in overcoat for this purpose.

Even though the chasseurs d'Orleans had received the first "Minie" rifle model 1846 in September 1848, the line infantry of the Crimean War retained the 1842 percussion musket - basically a percussion version of the 1822 musket. However, a rifled version was issued to some voltigeurs. This weapon, incidentally, was later rebored to supply the line infantry. It was then known as the 1843T (Tige).

For the 1859 campaign, the French infantry of the line was again to take the field in red kepi, blue-gray capote, and pantalon rouge. The epaulettes were as before.

During 1860-61 the line and chasseurs adopted a tight-fitting short-shirted tunic like that of the Guard Chasseur Battalion. It is said to have been uncomfortable and impractical, but very stylish. The red trousers were shortened and attached to longer gaiters.

Perhaps the most curious thing about this garment which replaced the more comfortable and practical tunic, is that it was worn in the field. The capote of the same vintage, still of bluish iron gray, no longer had shoulder tabs, nor was the collar or cuff trimmed. It had a large turn down collar, and was not to be worn alone, but only as an outer garment over the new tunic. Even stranger, the short shako was once again to be worn in service! Thus the least practical dress uniform of the line infantry in a generation was also to be worn in battle - although it is noted that the kepi was still permitted for service wear outside of Metropolitan France.

The principal theater of operations in which this strange uniform was worn, as it turns out, was even less practical than the garment itself Mexico. Le Sabertache provides an illustration of a grenadier of the 95th of the line in Mexico in 1862 wearing a broad brimmed hat covered with white cloth bound in black. The short dark blue tunic, or Basquine, has jonquil yellow trim, collar of the same color with blue trim, length of service stripes and pantaloons colored in madder, white gaiters, and black shoes. As a grenadier naturally, he wears madder epaulettes. The knapsack is still of fawn leather with black belting, and the "useless" sabre briquette with brass hilt still strapped alongside the triangular bayonet with black leather scabbard and brass tip.

On the other hand, we should not conclude that the dapper new outfit was universally worn in the field - even allowing for the local variations (like the slouch hat). A contemporary voltigeur is shown in Africa with the same belting, etc., but wearing the capote with his jonquil epaulettes affixed. On his head isworn a kepi - but it is entirely covered with a white cloth covering which comes down over the neck in the familiar Hollywood Foreign Legion fashion. But this fellow isn't a foreigner, he is a corporal of the 66th ligne. Except for the fall collar and the short pantaloons- which are not that different in appearancefrom the longer ones tucked into the tops of the gaiters, he does not look that different from a soldier in the 1859 or 1870 field uniform. This should also serve to confirm that the white kepi and neckcloth need not designate a soldieras a member of the Foreign Legion.

The final pre-1870 uniform change occurred as a result of decrees of December 1867 and January 1868. Under these decrees the tunic became double breasted. and returned to its 1859 length. The collar remained yellow with blue trim, and a thin yellow piping down the front. The yellow piping also applied to the cuffs. The shako was of stiff black felt with a blue turban at the bottom on which the regimental number appeared. The cockade was of white metal and a double pompom topped it off - on the lower one appeared the company number in brass, the upper one varied according to the battalion of the regiment - royal blue, madder, or jonquil (yellow).

Probably the most important thing about the tunic and shako of the 1868 uniform was that they were no longer expected to be worn in battle instead the new capote, with rounded collar, madder collar patch, and a double row of sixteen brass buttons, became once again the standard field dress. There was a simple and rather short vest which could be worn under it in place of a tunic. A short kepi was retained as usual with madder top and blue turban with blue vertical trim. The regimental number appeared on the blue turban in front as for the shako.

Even more important, this equipment more or less coincided with the issue of the fusil d'infanterie modele 1866 "Chassepot". This 11mm (44 cal.) weapon was, in comparison with earlier French shoulder arms of the infantry, state-of-the-art. its range has been variously estimated at 900 to 2000 yards - but for practical purposes it was limited only by the skill of the user - which proved to be unexpectedly high. The issue of the Chassepot was accompanied by the issue of the saber bayonet, a weapon already in use with the Minie rifles of the Chasseurs and Zouaves. This device replaced both the angular bayonet and the saber briquet, and might more properly have been termed a "yataqhan" bayonet since to avoid interfering with the path of the bullet it had a reverse curve. The length was 57.3cm, the hilt brass, the scabbard steel. With the abolition of elites (who became 1st class soldiers) the scarlet epaulette became universal, so the chief visible differences between the fantassin of 1859 and 1870was the white metal scabbard and the universally red epaulettes.

So much for appearance. For most of the Second Empire,the organization of the line infantry was essentially that of the First Empire, and the regulations which governed their use were essentially those of the regulations of 1791. The normal strength, on paper, was 6 companies. Each had 3 officers, 5 NCO's,and 75 men,and each battalion had the two elite (grenadier and voltigeur) and 6 center (fusilier) companies. From time to time in wara 4th depot battalion would be added. However, while the paper strength should have been 2,031 counting the regimental staff and battalion staffs, in 1870 it was impossible to field some battalions at a rated strength of 500 men, now in 6 companies.

Perhaps the greatest change in regulations was the adoption in the regulation of 1862 of the two rank line. This was already in use among the Chasseurs, and probably the zouaves. Adjustments before 1870 were incomplete, but reflected for the first time in the history of the French line infantry a recognition of the primacy of firepower. The 1870 instructions showed a substantial acceptance of defensive tactics - but the text in any case was adopted too late to substantially change instruction. However, if we are to call the French conservatives for going to the 2 rank line of battle in 1862, bear in mind that the Prussians, or I should say the German Empire, kept the triple line until the 1880's.

More Franco-Prussian Armies of 1870

Part II: French Army: Line and Light Infantry

Napoleon III (The Little)

Napoleon III (The Little)

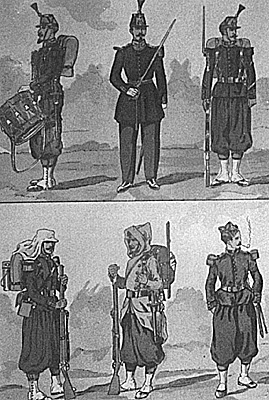

French line infantry in the much despised 1860-67 uniform. Note "Crimean" style capote and briquet and bayonet shown on bottom center figure.

French line infantry in the much despised 1860-67 uniform. Note "Crimean" style capote and briquet and bayonet shown on bottom center figure.

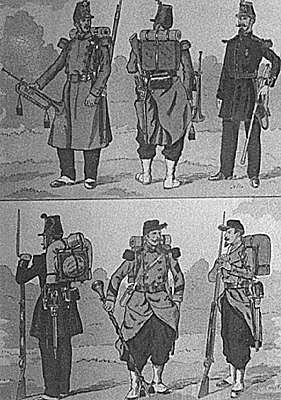

French line infantry around 1850-1860. Shako on top row and bottom left. Full dress bottom left. Normal field uniform with kepi bottom right.

French line infantry around 1850-1860. Shako on top row and bottom left. Full dress bottom left. Normal field uniform with kepi bottom right.

Part I: Prussian Cavalry: Introduction

Part I: Prussian Cavalry: Hussars

Part I: Prussian Cavalry: Cuirassiers

Part I: Prussian Cavalry: Dragoons

Part I: Prussian Cavalry: Uhlans

Part II: French Army: Chasseurs a Pied Infantry

Part II: French Army: Zouave Infantry

Part II: French Army: Turco Infantry

Part II: French Army: Cavalry

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #2

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1986 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com