By far the vast majority of battles are fought across terrain which, although undulating in nature, is far from presenting the type of high ground found at Bussaco. Even the Pratzen Heights of Austerlitz fame are a lot lower than one would expect. Indeed, the point was well made by Steve Payne (Vol. IV, No. 3) when he remarked that the 'effectiveness' of terrain undulations was more a matter for the visibility rules than for the movement-penalty rules.

Using the Low Ground Line system (Vol. IV, No. 3), we can not only represent the tops of features, but their slopes down to their lowest points.

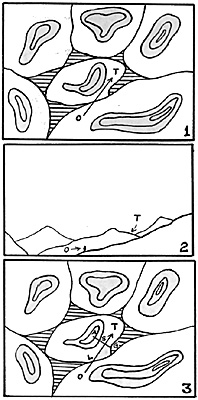

Let us consider drawing #1 from the observer's point of view (i.e. as an

elevation of that 'plan'). Where the actual model terrain

feature is not directly between the observer and target, but

a slope exists according to the low ground system. In

drawing 2, the target may be hidden by the shoulder of the

hill, which may not have been obvious from drawing 1.

Let us consider drawing #1 from the observer's point of view (i.e. as an

elevation of that 'plan'). Where the actual model terrain

feature is not directly between the observer and target, but

a slope exists according to the low ground system. In

drawing 2, the target may be hidden by the shoulder of the

hill, which may not have been obvious from drawing 1.

As a direct consequence of this, the term 'out of sight' can be just as relevant to troops on the table's flat surface when using the low ground line system as it can be to those that are directly behind a represented feature.

The main problem in producing visibility rules using the low ground line concept is that, unlike the traditional system-where the 'sides' (or 'shoulders') of the various features were obvious to the players (because they were the sides of the material used to depict the features) the shoulder of a hill that continues along the flat table surface is not. The first thing to do, therefore, is to define that shoulder in such a way that it will apply regardless of the observer's position, since the very nature of terrain causes its shoulder to change in relationship to the point of the compass from which it is viewed.

Therefore ' the shoulder of any feature will be taken to be on a line at right angles to the observer's line of sight to the target, and runs from the feature's highest point to the low ground line. This is shown in Drawing 3.

In drawing 3 the line AS represents the shoulder of the feature in the center of the battlefield as it would appear to the observer. Since it intervenes between the observer and what he is trying to see this tells us thateven though both are, in fact, on the flat table surfacethey are not visible to one another. The observer, consequently, cannot see the target, nor therefore can he issue orders in respect to it or what it is doing (e.g. -if the observer happens to be an artillery battery, it cannot f ire at the target).

To depict that there would be a valley between features, I have used the ruling that if the line of sight between observer and target lies within 100 yards of the low ground line when the feature's shoulder does not act as an obstruction to visibility. Readers with a more mathematical bent than I have might like to take that ruling further, and make the distance from the low ground line at which a feature will not obstruct visibility a function of the distance between adjacent figures so that hills that are far apart will be more likely to have wide valleys between than those that are almost on top of one another.

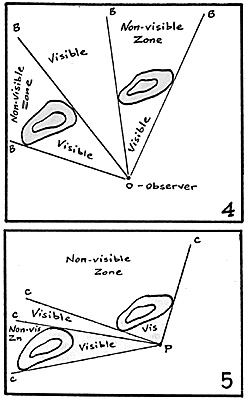

Human visibility is not something that is done on a narrow straight line. However the limit of visibility is something that can be defined using straight lines. As can be seen from drawings 4 and 5, which represents the "traditional" standpoint on terrain and visibility, the effect of a ground mass being present within the visibility circle (the 360 degrees of visibility that an observer can achieve by simply turning round), is to produce 'Non-Visible Zones' within that circle. Although this is nothing new in wargames' experience, I make use of a 'Visibility Stick' (any straight-edged piece of wood will do) so that, by simply laying it down between the observer and his target (or the edges of a feature) it is visibly obvious what he can and cannot see.

Human visibility is not something that is done on a narrow straight line. However the limit of visibility is something that can be defined using straight lines. As can be seen from drawings 4 and 5, which represents the "traditional" standpoint on terrain and visibility, the effect of a ground mass being present within the visibility circle (the 360 degrees of visibility that an observer can achieve by simply turning round), is to produce 'Non-Visible Zones' within that circle. Although this is nothing new in wargames' experience, I make use of a 'Visibility Stick' (any straight-edged piece of wood will do) so that, by simply laying it down between the observer and his target (or the edges of a feature) it is visibly obvious what he can and cannot see.

In drawing 4, the visibility stick would be represented by the lines AB and in a few seconds we would be able to tell just what an observing general at point 0 would be able to see (and react to) on the game table. If he changed his position, to P, drawing 5 then another few seconds with the stick would tell us immediately the effect of that change on his ability to see things on the table, indicated by the lines PC.

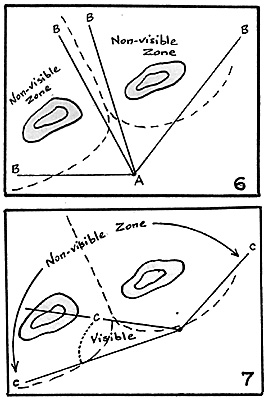

Using only terrain features themselves to block visibility, means that most of the flat table surface is visible to the general -generally the opposite case to that which exists on the battlefield. In drawings 6 and 7, therefore, I have shown how the use of the low ground concept would alter the visibility of the observer in drawings 4 and 5 by including the slopes created by the low ground line as obstacles to vision. In this way the wargamer can restrict visibility even if using a flat table with a minimum of terrain. This, in turn, will limit the abilities of commanders to instantly see and react to events which should lead to a more realistic battlefield result.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1983 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com