Officer Corps

Much is made by some of the so-called "purge'' of the officer corps in the wake of the defeats of 1806, but, to repeat a phrase often used throughout this essay, an objective analysis of the available facts paints quite a different picture

Of the 7096 officers in the army at the outbreak of the war in 1806, a mere 208 were dishonorably discharged. Another point worth noting is that of the 6905 officers in the army in August 1813, some 3898 had fought in the campaigns of 1806/7 so, in this sense at least, the Prussian officer corps of 1813 was largely that of 1806.

Bleckwenn, in his "Unter dem Preussen-Adler'' illustrates this fact by pointing out that every Prussian officer holding the rank of captain upwards and many of the lieutenants in 1813 had already served in 1806, so the practices used at battalion and company level in the army at Jena could therefore not be vastly different from those used at Leipzig. In the conclusion to this essay I will attempt to draw out what I feel were the significant differences between the two.

As far as the officer corps is concerned, there were two important changes. Firstly, access to it was not as restricted in 1813 as in 1806. From 1808, entry was granted on the basis of the performance in an examination and not by birth. The officer corps was thus opened up to the bourgeoisie, but it would be many more years before a significant change in its social composition was made.

Secondly, and much more importantly, there were changes in the command structure at higher levels, some of which were mentioned in the section dealing with brigade formations. With the right machinery in their hands, the generals of 1813 were able to operate and command their formations much more effectively than in 1806. A number of generals who had held senior commands in 1806 continued to do so in the campaigns of 1812-1815 including Grawert, Bluecher and Tauentzien.

What was different in 1813 was not so much the men giving the orders but the more efficient staff work which gave them better information with which to give the right orders and the command structure which allowed those orders to be properly carried out.

THE ARMY CORPS

Having now dealt briefly with the theory of the conduct of warfare and training of the army, let me mention the effects of the mobilization of 1813. Until now, we have been considering the peace-time brigades of 1809-1812.

The auxiliary corps of the 'Grande Armee' consisted in part of odd battalions taken from various regiments and organized into "combined regiments", all six of which were each of two musketeer and one fusilier battalion. The brigades consisted of two regiments that is battalions, so clearly the seven battalion formation as given in the 1812 Drill Regulations was subject to adaptation.

When we come to the mobilization of spring 1813, the picture is even more confusing in that the regiments and brigades which had sent battalions to Russia could not be re-united due to the circumstances of the outbreak of the war-the auxiliary corps was in East Prussia, so its battalions could not return to their respective regiments. Then a number of reserve battalions were mobilized and added to the brigades, so each brigade varied in size and strength.

By the time we come to the autumn of 1813, the 'Landwehr' militia battalions were added to the brigades and by this time no two brigades were of the same composition, some had two line regiments and one militia, some one line and two militia, some with one line, one reserve and one militia, and so on. Some brigades were so large, they were internally divided into two "brigades". Obviously the deployment of the battalions varied according to the individual circumstances, but consisted in every case of three basic elements-the skirmish line, the main battle line and the reserve.

How Brigades Were Used At Corps Level

How Brigades Were Used At Corps Level

Of greater interest to wargamers of grand tactical battles is how these brigades were used together within the army corps. The 'Royal Instruction of 10th August 1813', issued to all regimental, brigade and corps commanders, gives us an outline of how an attack by a corps of four brigades should have been carried out.

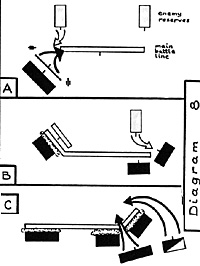

Several battalions in skirmish order were engaged against one of the enemy's flanks and supported by artillery fire being backed up by the remainder of the brigade. The object was to attract the enemy's attention and draw his reserves. The battalions of this brigade would hope to delay the enemy for several hours by deploying into line and skirmish order and engage him in a protracted firefight. See diagram 8A.

As soon as the enemy began to commit his reserves against the feint, the main attack with two brigades would commence. Emphasis was placed on concentrated artillery fire aimed at the main point of the attack. One of the two brigades would engage the enemy flank while the other waited for the opportune moment to attack frontally, see diagram 8B.

The reserves were to be committed at the point needed and the cavalry reserves to be used for outflanking manuevers, see diagram 8C. The three main elements of a corps attack were therefore the feint, the main attack and the reserve.

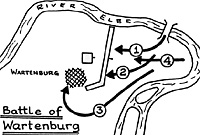

In practice, circumstances such as terrain and enemy reactions obviously affected matters and it would be useful to examine briefly one battle of the autumn campaign to see how this worked. At the Battle of Wartenburg (3rd October 1813) Yorck's Corps engaged Marmont,

Initially, one brigade was used as a feint to draw the attention of the French (Arrow 1) while the others crossed the Elster bridge and deployed. A second brigade was used to tie the French position (Arrow 2) while a third outflanked their position (Arrow 3). The fourth was used as a reserve where needed (Arrow 4). Here we see how the feint, main attack and reserve were used in a battle situation.

This is where there was the great contrast between the army of 1806 and 1813-at regimental, brigade and corps level, maneuvers were co-ordinated and all three arms acted in support of each other. Although the attack column was introduced, the line continued to be used where required and the Prussians varied their tactics at all levels to the local circumstances. They were not "committed to the column and skirmisher tactics" as such, but used them where necessary. Skirmishers were used to prepare the ground for a bayonet charge by the columns and the line was used to engage in a firefight.

Paret's view (see The Courier III/5, p. 18) is somewhat of an exaggeration. The Prussians did not swing from one extreme to another between 1806 and 1813. In 1813, they showed a good deal more flexibility in that they used various formations according to circumstances, but where the important difference lay was at the regimental, brigade and corps level. What the individual battalions did was a secondary issue. So long as they acted in concert, it was not so important if they were formed in column or line.

CONCLUSIONS

What were the main differences between the army of 1806 and that of 1813? They included the following:

- The introduction of the attack column as opposed to the line as the favored formation for the infantry battalions.

- An increase in the number of light infantry, especially at battalion level from around 50 men for a 600 man battalion in 1806 (1:12) to a potential number of 260 for a battalion of 800 men in 1813 (1:3), although usually no more than 40 or so would be skirmishing at any one time (1:20).

- The introduction of integrated training of all arms at brigade level and the development of the command system for the tactical control of the army corps.

To the author of this essay, the above does not indicate a radical break with "tradition" or the "wholesale introduction of the French system", the view held by certain historians, but rather the natural and logical development of the system already existing in 1806.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I think that little would be gained by simply drawing up a list of every work consulted in the preparation of this article, instead, I shall provide a selection of further reading.

The works of Curt Jany, one of the most notable historians produced by the German Grand General Staff must form the basis of any study of the Prussian army. Most of the dates, facts and figures given in this essay come from the 3rd and 4th volumes of his: Geschichte der Preussischen Armee (reprinted Osnabruck 1967). Two earlier essays of his, namely: Die Gefechtsausbildung der Preussischen Infanterie von 1806, and: Der Preussische Kaval/eriedienst vor 1806 provide an informative analysis of the tactics of the army along with a number of official reports to illustrate his points.

A further important work published by the General Staff is: Das Preussische Heer der Befreiungskriege (3 vols., Berlin 1912-1914). The first volume provides a useful explanation of the 1812 Regulations.

No study of the tactics of this period would be complete without having refered to the Regulations of 1788 and 1812 both of which may be appearing as a reprint later this year.

An important work on the officer corps in 1806 is: 1806-Das Preussische Offizierkorps und die Untersuchung der Kriegsereignisse, published by the General Staff in 1906.

For a good overall view of the development of tactics in Europe, reference to Herbert Schwarz's Gefechtsformen der Infanterie in Europa durch 800 Jahre (Munich 1977) is essential.

- The introduction of the "attack column" as the main battlefield formation.

- The establishment of mixed brigades of all arms as a peacetime formation as well as the basis for the tactical formation on the field of battle.

- An increase in the number of light infantry.

- The opening of the officer corps to the bourgeoisie.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV No. 2

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com