Light Infantry

Much is made of the potential numbers of light infantry in the "reformed" brigades of the "new" army. Up to half of an infantry regiment-the fusilier battalion and the third rank of the two musketeer battalions-were trained to operate in open order as per the 'Instruction of

27th March 1809'. However, a number of historians and wargamers tend to take this information at face value and talk about the Prussians operating with half of their brigades in skirmish order. This misapprehension is caused by a misunderstanding of what skirmishing in the days of the muzzle-loading flintlock musket actually consisted of.

Much is made of the potential numbers of light infantry in the "reformed" brigades of the "new" army. Up to half of an infantry regiment-the fusilier battalion and the third rank of the two musketeer battalions-were trained to operate in open order as per the 'Instruction of

27th March 1809'. However, a number of historians and wargamers tend to take this information at face value and talk about the Prussians operating with half of their brigades in skirmish order. This misapprehension is caused by a misunderstanding of what skirmishing in the days of the muzzle-loading flintlock musket actually consisted of.

At right, fusilier, parade dress 1809-1814. Source: Kling.

Fighting in loose order was in reality a highly organized matter and not just a question of spreading men out over a wider distance. The main handicap to doing so was the very limited capabilities of contemporary weaponry. The firer dare not go too close to the enemy and fire as, due to the time it takes to load this weapon, the enemy could be on top of the firer smashing his head in before he had the chance to reload it.

It was difficult to make full use of available cover as loading this weapon prone or kneeling was a good deal more awkward than doing so standing. This should be borne in mind when reading accounts of skirmishers firing from "behind cover". As most muskets were more accurate at close ranges and the time it took to load such a weapon encouraged the skirmisher to fire at long

ranges, one should bear in mind that "aimed" skirmisher fire was not always more accurate than unaimed volleys. The use of cover was dependent on enemy actions. Unless he was obliging enough to stand in front of your position for a period of time, you would have to follow him, often fighting in the open and thereby making you vulnerable to his counter-measures and especially to cavalry.

The proximity of close-order reserves was essential for the survival of one's own skirmishers for that reason and for others. Amongst the other reasons are the nature of the single-shot muzzle-loading weapon. The loading procedure was long, complicated and physically tiring. It

would be exhausting to load and fire such a musket over a long period of time and anybody that did would be useless for the rest of the battle.

Furthermore, continuous uninterrupted firing would overheat the barrel of the musket, increasing the chance of it exploding in the firer's face and thereby reducing the efficiency of the skirmish line not to mention that of the unfortunate firer. Then there was a limit to the amount of ammunition a soldier could and did carry anyway. Once the cartridge box was empty, getting to the reserve supply carried usually in the backpack was difficult when in the line of battle. To get to the battalion ammunition wagon would certainly mean being withdrawn from the front. The "super skirmisher" who fought for hours uninterrupted and won battles single-handed and was a physical impossibility is the stuff of pop historians.

Although frequently seen, this figure deserves no place on the wargames table. The Napoleonic skirmisher was a limited weapon closely tied to and very dependent on his close-order supports. Only the introduction of new technology that came with the introduction of the breach-loading rifle could create the independently operating skirmisher who could make full use of cover. To

illustrate how infantry skirmishing functioned, I will examine the relevant section of the Prussian Infantry Drill Regulations of 1812.

The section entitled: Regulations for the Third Rank was based on those published by Prince Hohenlohe in 1803 (see Part I in The Courier III/5, p. 20) which were issued in a modified form in 1809 and subsequently published in the 1812 Regulations. The

introduction of this section makes it clear that the purpose of this training was to produce the "universal infantryman", that is a soldier capable of operating in both close and

open order as opposed to the "specialist infantryman" of the previous century, that is a grenadier, a musketeer, a rifleman, etc.

Although the fusiliers and third-rankers were specially selected for their aptitude for functioning as light infantry, they were also expected to operate efficiently in close

order. Conversely, the first and second ranks were likewise expected to operate in open order when required.

A degree of specialization remained in that specific men were selected for a specific task, but on the other hand, all were expected to perform every task when called upon. We saw in the earlier parts of this essay that prior to 1806, there were'experiments leading in this direction. From 1809, the creation of the "universal infantryman" was now a formally accepted goal.

The third rank could not only skirmish in support of the main body of the battalion, it could also operate independently of the main body, forming a van or rear guard, patrols, as a reserve, and to occupy defensive points, etc. They were formed into platoons two ranks deep for this purpose. The third rank of a battalion could be formed into four platoons which were commanded by a mounted captain. Each platoon was commanded by one officer and three NCO's. Initially, the skirmisher platoons would be formed up behind the flank platoons of the main body of the battalion. They were then used alternately in a skirmish role as and when needed.

These platoons were required to function in the

following circumstances:

And this is done as follows:

It is interesting to note that although the firefight is to

be carried out by the third rank, care is to be taken not to

get the formed troops involved except to make the decisive

bayonet attack at the crucial moment.

Although the third rank was designated to perform a

skirmish role, that does not mean that every man in the

skirmish platoons fought in open order simultaneously.

The Regulations state:

The third rank fights here (when trying to delay an

enemy line for a specific time-PAH), assuming that the

enemy does not press forward in too great a strength, only

partly deployed, using from 1/3 to at the very most 2/3 Of the

total. If the entire third rank was to deploy without any

reserve, it would soon use up all its ammunition.

(p.100)

The skirmish platoons of the third rank also had to

keep at least part if its men in close-order so that the

skirmishers had a point to fall back on when rallying.

Taking the average battalion at 800 men strong, each

skirmish platoon would be around 60-70 men strong and

between 20 and 45 of them would be operating in loose

order. With two such platoons forming the battalion's

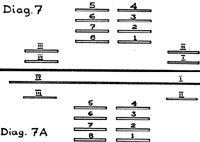

skirmish line and two in reserve (see diagram 7A), then

between 40 and 90 men would be operating in loose order,

some 5% to 12% of the total of an 1813 battalion.

An 1806 battalion operated with up to 8% of its men in

loose order, so where is this great difference that so many

historians talk about when comparing the light infantry

tactics of 1806 with those of 1813? Of those men

operating in loose order, no more than half would be firing

at any one time as, operating in teams of two men, one

would hold his fire to cover the other while he loaded.

Taking into account the time expended moving forward

and selecting a target, each skirmisher would not be firing

more than once every few minutes in most circumstances,

so the fire of the skirmish line would not be "devastating''

by any stretch of the imagination, yet one often reads

accounts describing it as such.

The fusiliers functioned along broadly similar lines

except that of course the entire battalion could be called

on to deploy for a skirmish fight should it be detached

from the brigade. In that case, each of the four companies

was formed into three platoons two ranks deep which were

used alternately in the skirmish action. When operating in

conjunction with the brigade, usually only the third rank

was pulled out of the battalion and so deployed.

When reading accounts of battalions being "deployed

into skirmish order", etc., one should bear in mind that the

majority of the members of that unit are in fact still in

close order, supporting the skirmishers. The important

difference between a battalion operating in close order and

one in open order is that the function of the latter is to

engage in a firefight whereas the former is holding itself

ready for a bayonet charge.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. DIAGRAM 7 (top): Skirmish platoons on the flank of the parent battalion.

DIAGRAM 7A (bottom): Skirmish line and skirmish reserve formed by platoons of

the 3rd rank.

DIAGRAM 7 (top): Skirmish platoons on the flank of the parent battalion.

DIAGRAM 7A (bottom): Skirmish line and skirmish reserve formed by platoons of

the 3rd rank.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV No. 2

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com