DISPOSITION FOR BATTLE:

DISPOSITION FOR BATTLE:

APRIL 5, 1242

The Battle of Lake Peipus was restaged as a wargame scenario utilizing WRG sixth edition rules and the screenplay and stage directions from Serge Eisenstein's classic movie, Alexander Nevsky.

Special acknowledgement also is made to Jay Stone and Dave Waxtel who furnished the figures for this recreation.

Army compositions were as follows:

| Unit | Classification | Size | Points | Figures Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Teutonic Order: | ||||

| Brother Knights | EHK (Irg A) Lance | 12 | 217 | FP-1/FH-1 |

| Brother Sergeants | HC(Irg C) Lance | 12 | 121 | FP-27/FH-3 |

| Halbbruder | HI(Reg C) LongSp | 24 | 154 | FP-34 |

| HI(Reg C) LongSp | 24 | 154 | FP-34 | |

| Ordenstaat | LI(Reg D) Javelins | 6 | 23 | FP4 |

| Skirmishers | LI(Reg D) Javelins | 6 | 23 | FP4 |

| Danes | LHI(irg C) 2h Ax | 18 | 115 | FP40 |

| Lithuanians | LMI(Irg D) Lt.Sp | 18 | 61 | FP-6 |

| Commander (Conrad von Thuringen) | EHK | 1 | 100 | FP-2 |

| Total | - | 121 | 968 | - |

| Novgorod | ||||

| Druzhina | HC(Irg B) Lt.Sp | 15 | 160 | FP-17/FH-3 |

| Polk | HI(Irg C) Lt.Sp or 2h Ax | 24 | 145 FP-19/20 | |

| HI(Irg C) Lt.Sp or 2h Ax | 24 | 145 | FP-19/20 | |

| HI(Irg C) Lt.Sp or 2h Ax | 30 | 175 | FP-19/20 | |

| Peasantry | LMI(Irg D) Lt.Sp OR | 15 | 55 | FP-22/AP-194 |

| LMI Throwing Ax | 15 | 55 | FP-22/AP-194 | |

| Commander (Nevsky) | HC | 1 | 100 | FP-18/FH-3 |

| Total | - | 124 | 8358 | - |

Why did Nevsky choose to fight on the ice? The device of the Russian fairy tale reproduced above was used in the movie to describe Nevsky's logic to his troops and to the audience. Other possible motives include:

- 1. Russian familiarity with plains warfare. It was

relatively easy to deploy and manage formations on a

flat surface, and the ice on Lake Peipus simulated that

environment very well.

2. The icy surface of the lake was slippery and would impede mounted charges. The Teutonic superiority in cavalry was recognized, and the ice might nullify this advantage. indeed, many Brethren fought dismounted in this action. Subtract -10 paces from cavalry and -1 from cavalry charge bonuses.

3. The weight of the armored Germans and their horses could lead to the ice breaking. This possibility was especially true around the thinner surfaces of the lake's edges. A die roll of 2-5 for EHK, and 3-5 for HC and HI/LHI at the edge of the lake would reproduce this event within the wargame scenario.

Nevsky dispatched his vanguard to intercept the Germans at the western edge of the lake in order to give the rest of his army time to deploy. Although that vanguard was surprised and almost destroyed, it achieved its strategic purpose of slowing down the Order's army according to Nevsky's plan. Nevsky would fight on terrain of his choice.

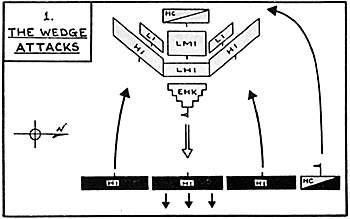

THE ATTACK OF THE TEUTONIC WEDGE

The Teutonic Knights adopted their famous wedge formation for this battle. The Russians, incidentally, nicknamed it the "swine" for its tough snout and bulky mass. The wedge had the advantage of being compact and not easily stopped once in motion. The Hochmeister, Conrad von

Thuringen, took his place at the wedge's apex; his retainers and mounted Knights followed up as the principal strike force. The Hochmeister could select the initial point of impact and

then rely on the wedge's powerful forward momentum to split the Novgorodian line in half.

The Teutonic Knights adopted their famous wedge formation for this battle. The Russians, incidentally, nicknamed it the "swine" for its tough snout and bulky mass. The wedge had the advantage of being compact and not easily stopped once in motion. The Hochmeister, Conrad von

Thuringen, took his place at the wedge's apex; his retainers and mounted Knights followed up as the principal strike force. The Hochmeister could select the initial point of impact and

then rely on the wedge's powerful forward momentum to split the Novgorodian line in half.

The Order's infantry kept pace with the cavalry at the run, preserving the wedge's cohesion. Skirmishers, Danish mercenaries and Lithuanians accompanied the heavy infantry, composed of dismounted Knights, Sergeants and Halbbruder. The light infantry would be released to pursue the fleeing Russians or to hinder them if the assault failed. If the wedge halted, the infantry would fan out into a line to prevent the enemy from outflanking it. The remaining mounted Brethren brought up the rear to discourage stragglers or to wheel to either flank if threatened by an outflanking maneuver.

The beginning of the battle went as planned by the Teutons. The Russian center was pushed back in disorder, and for a while it appeared as if the unit commander there was either killed or severely wounded.

NEVSKY'S COUNTER-ATTACK

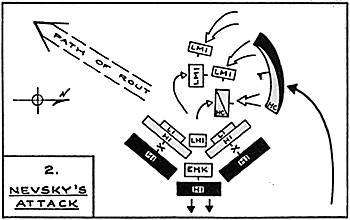

Nevsky had envisioned the wedge's irresistible force and had instructed his center to give ground slowly rather than to try and hold. Meanwhile, he led the Druzhina on the right flank

to swing around thewedge in order to threaten it with being surrounded. His remaining two infantry units also would turn inward to engage their opposite heavy infantry. Ideally, all of

this maneuvering would force the wedge to grind to a halt and assume the defensive.

Nevsky had envisioned the wedge's irresistible force and had instructed his center to give ground slowly rather than to try and hold. Meanwhile, he led the Druzhina on the right flank

to swing around thewedge in order to threaten it with being surrounded. His remaining two infantry units also would turn inward to engage their opposite heavy infantry. Ideally, all of

this maneuvering would force the wedge to grind to a halt and assume the defensive.

In addition, Nevsky had posted his peasant contingents behind cover along the northern edge of the lake. They would allow the Germans to pass and then ambush them from behind after battle had been joined. This step would complete the encirclement of the wedge.

The next phase of the battle proceeded according to Nevsky's plan. The wedge had to divert its attention from splitting the Russian line in two in order to defend itself. The Order's light infantry tried to disrupt the Russian counterattack but were thrown back. The Order's heavy infantry halted and formed up in close order but were unable to expand their line outward. As the mounted Brethren in the rear turned to face Nevsky's Druzhina, the peasants suddenly attacked them in the flank; disorder and then rout began among them and the Lithuanians. Their defeat spread the contagion of rout to the rest of the Order.

THE ICE SLAUGHTER

When the Germans realized that their formation had been broken their defense crumbled. They routed five miles across the frozen lake to the steep banks of its western edge. The ice first cracked beneath the massed fugitives fleeing the battle and then broke. Many Germans and some Russians fell through the ice and drowned. The Teutonic Knights especially suffered: over 400 Knights died while another 50 including the Hochmeister were captured. Nearly all of the Lithuanians were killed or captured and the rest of the Order's army sustained heavy losses. The Russians also had many casualties, but they stifled the Teutonic threat to their independence.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe.1979

Eisenstein, Sergei. Notes of a Film Director (trans). 1970

Florinsky, Michael T. Russia: A History and Interpretation, vol 1. 1953

Fr-Chivovsky, Nicholas L. A History of the Russian Empire, vol 1. 1973

Heath, Ian. Armies of Feudal Europe: 1066-1300 A.D. 1977

Leyda, Jay, ed. Eisenstein: Three Films. 1974

More Ice Slaughter

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com