The best way to get an idea of the tactics used on a regimental and battalion level and their effectiveness is to refer to reports of regimental and battalion commanders and this is exactly what I propose to do. A number of such reports were made by Prussian officers and they are remarkably lucid and objective. The various tactical aspects will be considered under the relevant heading.

The 3rd Rank as Skirmishers

Already been mentioned in the first part of this essay,the use of the third rank of a line infantry company in a skirmish role evolved in the Prussian and Austrian armies at around this time. This practice was formally adopted in the 1812 regulations. Some use of the third rank was made in 1806, as the following quote from Major von Lessel's report shows:

- "Since the [Schuetzen] ( Prussian skirmishers from the

line formations. ) were not able to drive the Tirailleurs

(French skirmishers from the line formations) out of

the forest, General von Sanitz had reserves formed from the

third rank of the corps and threw them into the wood too."

Note that this was not some tactical initiative by a bold, young battalion commander, but an instruction issued by a senior officer.

Jany, on page 495 of volume III of his history of the Prussian army mentions the use of the third rank to fill the gaps between the battalions and in a skirmisher function. In 1806, this use of the third rank was comparatively rare, by 1813 it was standard practice, as we shall see later.

FUSILIER OFFICERS, 1806.

FUSILIER OFFICERS, 1806.

Source: Kling

Tactics Against French Skirmishers

This section will hopefully provide wargamers with some ideas and inspiration. The first report quoted from here is that of 2nd Lieutenants Barons von Eberstein I and II and refers to the role of infantry Regiment Count Wartensleben No. 59 in the Battle of Auerstaedt:

-

"At the foot of the mentioned chain of heights, when we formed front so as to occupy it, on advancing we were immediately harassed by French skirmishers whom the regiment did not allow to throw it into confusion, and did not return a single shot, rather it reached the heights in a calm advance and forced them back almost a quarter of a mile during which fatalities occurred in that the limber of the battalion gun behind the right flank went up in the air, wounding a group of men on the right flank of our 1st Battalion some badly, some slightly. Due to the enermy skirmishers themselves, the 1st Battalion of our regiment had hardly lost 20 men, as, on the contrary, they had suffered somewhat of a defeat from the cannister fire of our battalion pieces, the effects of which we saw from the dead over whose bodies we advanced."

The tactics used by this battalion at the beginning of the battle are interesting to note; French skirmishers could neither stop nor hinder an advance by formed troops and were put to flight by the cannister fire of the battalion pieces. The close-order Prussians were neither confused nor demoralised by the French skirmishers. This point is emphasised by reference to the part of the report dealing with the latter part of the battle:

- "We now came up to their reserve formed in squares which greeted the remnants of the battalion with a hefty musketry and cannister fire. And only the fact that, as we again had to

fall back, successive troops of 40 to 60 (French) skirmishers sprang out of the squares and attacked us - possibly to take our colour from the group reduced to barely 150 men which

was retiring in a crescent (see later) - this had only a favourable effect for us as the squares neither fired not gave us any volleys, we only had to endure the fire of the

skirmishers who were only slowly followed by the mass of the enemy. The small remnant of our battalion had fired off nearly all of its cartridges. To receive fresh supplies of ammunition

was out of the question. Cannister fire was now directed at us and with the greatest possible order, we retired slowly in a crescent whilst our men fought in a desperate way and knocked down the advancing skirmishers with their musket butts."

So far from demoralising the survivors of this regiment and throwing them into confusion, the appearance of French skirmishers proved a welcome relief. Only when supplies of ammunition had run out did the tirailleurs dare to come close to the Prussians. The "crescent" formation adopted by the latter is also worthy of note. On the order: "Flanquen formiert!" the tow flank platoons would wheel to cover the flanks of the line.

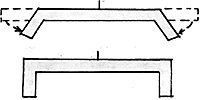

- 1. The Crescent Formation, when stationery.

- This formation would offer some protection to the flanks of the line from enemy skirmishers and cavalry. On withdrawing, these platoons would form a right-angle with the line, forming a sort of open square.

2.The Crescent Formation, when withdrawing.

- This formation is not one that could be called a "rigid" line, and combined the mobility of the line with some of the advantages of a square.

Now to the report of Colonel von Raumer, commander of Infanty Regiment No. 28 which was at Auerstaedt:

- "On 14th October, at daybreak, all the Schuetzen of the regiment, joined by a squadron of dragoons from the Queen's Regiment, were assigned to the command of Adjutant-General von Pfuhl to form a patrol ... and unfortunately the regiment had to fight the entire battle without Schuetzen ... and due to lack of Schuetzen, the left flank company of the battalion was used for that purpose."

This was a common practice made necessary by the inadequate number of light troops and the tendency of higher levels of command to deprive the regiments of their much needed light troops. We can see that to some extent, Prussian line troops were used in a skirmisher role, and it is hard to jusify Chandler's claim ('Campaign's of Napoleon', pp. 454) that: 'Tactically, 'the Prussian army was a museum piece, clinging to a rigid linear system of shoulder-to shoulder drill better suited to an earlier age."

Next, to the skirmisher tactics used at Jena, and the report of Colonel von Kalckreuth, commander of the Infantry Regiment Prince of Hohenlohe No. 32:

- "Right in front of the position that the regiment had now occupied was the large Isserstedt Forest, and a bit closer to the left was another copse, both of which were occupied in

strength by enemy skirmishers. From the smaller copse, the enemy was very soon dislodged by the Schuetzen of the regiment, however, the Isserstedt Forst would not be completely cleared of the enemy as it reached into the enemy position ......"

It is apparent here that Prussian skirmishers saw off their French equivalent and were only prevented from driving them right out of their position by the close proximity of close order troops. The report continues:

- "the Schuetzen of the regiment, spured on by their commanding officers, held back the enemy light troops for a very long time although the latter were protected everywhere by very advantageous terrain . . . ."

We can see from this that the Prussian skirmishes were capable of giving a very good account of themselves. Finally under this heading, to the report of Lieutenant-Colonel von Hallmann, a battalion commander in the Infantry Regiment Winning No 23:

- "The enemy line advanced and sent light troops after us, we formed front three or four times and fired, we had no Schuetzen, so Lieutenant-Colonel von Hallmann ordered 1st Lieutenant von Wobeser to cover the retreat with his company, and this he did as well as he could with

musketeers operating 'a la debande' . . ."

This is another example of the "inflexible" Prussian line troops operating in loose order.

To sum up on the question of the tactics employed by the Prussians to deal with French skirmishers, it can be seen from the above that the following methods were used:

- 1. An advance by close order troops to chase the tirailleurs away.

2. Cannister fire from the battalion guns to discourage the tirailleurs.

3. On retreating, the close-order troops adopted the "crescent" formation to protect their flanks from the tirailleurs.

4. Schuetzen, when available, were used against the tirailleurs in broken countryside.

5.When no Schuetzen were available, line troops, either entire companies or the third rank, could be used in their place.

Prussian Small Arms Fire

Some historians have been keen to latch onto Clausewitz's statement that in 1806, the Prussian musket was "the worst in Europe", distorting it to fit their arguments that the Prussian army was inferior to the French in every way and its attempts to defeat the French army by small arms fire were ridiculously stupid. However, an objective and sensible examination of the facts paints quite a different picture.

FUSILIERS IN FIELD KIT, 1806.

FUSILIERS IN FIELD KIT, 1806.

Source: Kling

In the first part of this essay, it was mentioned that under Frederick the Great, th Prussians developed their linear tactics to perfection. Alongside their ability to perform evolutions, the Prussian infantry was feared for its much superior rate of fire. It was not just intense training or iron discipline which achieved this, but a purposely designed musket.

Firstly, the Prussians were the first to have iron ramrods in place of the until then customary wooden versions. As the iron models did not snap, the Prussian infantry could be relied on to keep up their firing for longer than their opponents.

The next technical advances included the cylindrical ramrod which did not need to be reversed to push the charge down the barrel, thereby saving valuable seconds and the conical touchhole which allowed the pan to be primed at the same time as the charge was rammed home, saving even more time. The combination of thee features led to the Prussians being able to get off between three and five times as many volleys as their opponents. To facilitate this rapid firing, the butt of the 1780 model musket was designed to prevent aiming. Thus this model was inaccurate when compared with its contemporaries, but this greater inaccuracy was more than cancelled out by the much superior rate of fire of its users.

The 1780 model may well have been "the worst musket in Europe" when it came to accurate fire, but in the hands of the Prussian infantry it remained one of the deadliest. Of course, not being suitable for aimed fire, this musket was not at its best in the hands of skirmishers, but they were not issued with them anyway. The fusiliers had their own, shorter, more accurate weapon. The Schuetzen had a rifled weapon. The 1780 model obviously hindered the use of line troops in open order, but it was intended to replace that model with the 1805 Nothardt musket. After 1806, the 1780 model was re-issued with a redesigned butt and could be favourably compared with the accuracy of its contemporaries, as a reference to a series of tests carried out in 1810 shows:

| CHART 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUSKET MODEL/RANGE (paces) | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 |

| 1780 Model | 92 | 64 | 64 | 42 |

| Ditto, butt improved | 150 | 100 | 68 | 42 |

| 1805 Nothardt | 145 | 97 | 56 | 67 |

| 1809 New Prussian | 149 | 105 | 58 | 32 |

| French 1777/1802 Model | 151 | 99 | 52 | 55 |

| Brown Bess | 94 | 116 | 75 | 55 |

| Russian Model | 104 | 74 | 51 | 49 |

ED NOTE: I believe this refers to the number of hits on a standard target (Btn sized) at the range stated, the author gave no indication of the number of shots fired - I assume they are the same in each case.

In 1808, a man by the name of Faber, who had served in the French army, wrote:

- "It can be accepted that the French fire one round while the Prussian got off three against them and the Austrians around two."

It should be remembered that the French suffered severely from Prussian small arms fire. For example, at Auerstaedt, Davout's corps lost some 26% and Gudin's division at Hassenhausen 42%, virtually entirely from the fire of "the worst musket in Europe".

The Prussians fired volleys either in two or three ranks deep, then there was the "Battle Fire", that is independent fire by file. Also, alternate sections could fire, this usually against cavalry.

We now need to compare the use of small arms fire in the battles of 1806. Again, we shall refer to the official battle reports of the Prussian army. First, to Infantry Regiment No. 59:

- "The battalion halted, fired three volleys, which were likewise returned and we now engaged in a 'battle fire' (see above) lasting nearly three hours in which the battalion line continually advanced while the enemy always pulled back gradually, during which we advanced somewhat to the right, by which we had the opportunity to gain the flank of the enemy line and at the same time to secure the right flank of our battalion against a hill, which would protect us somewhat from an enemy battery that had moved in that direction to our right ... After the passing of the mentioned three hours during which the 1st Battalion had dwindled down to half-strength through dead, wounded and stragglers from this vigourously maintained and murderous small arms fire in which even enemy batteries fired at us, but most of the balls bounced over us, we noticed a reduction in the enemy fire and a wavering in the enemy line in front of us ... on noticing the reduced fire and the wavering of the enemy line, which may have been around 2 p.m., Major von Ebra, although already wounded, on foot at the head of the battalion with a colour in the hand, ordered an advance with the bayonet .... and we thus threw back the wavering enemy in front of us ... We now had just thrown back this enemy line . . . . when we came up to their reserve formed in squares, which greeted the remainder of the battalion with a hefty musketry and cannister fire."

We can see from this quote that in this instance, there is essentially no difference in the fire tactics used by the Prussians or the French. The lines would approach each other, engage in a firefight until one side showed signs of breaking at which moment the other side would press home with a bayonet charge. The French line was beaten by the Prussian musketry and it was the formed French reserves which halted the Prussian advance. No mention of the Prussians being thrown into confusion by clouds of skirmishers and then being smashed by a French column.

From the report of Major von Krafft, commander of the Grenadier Battalion Krafft, also at Auerstaedt:

- "The thick fog which limited visibility to 50 paces made it difficult to discover the enemy position and the battalion had hardly advanced 200 paces when it received several volleys

at about 50 paces from two enemy battalions of the 85th Line Infantry Regiment which were deployed in a long sunken road and which could not be seen at all. Without wavering, the

battalion fired two volleys at the enemy, but the momentary loss of several dead and wounded had such a disadvantageous effect on the battalion which consisted entirely of new men, to which the superior number of the enemy can also be added, so that several men fell back momentarily. Through the greatest efforts of all the battalion, it was brought back into order in a small hollow aout 60 paces back and led against the enemy again. Although the battalion was shot at with cannister in this second attack, it was nevertheless more successful and the two enemy battalions mentioned were, after a mutual, hefty musketry fire lasting a long time, thrown back in disorder, and in this, 1 captain, 2 subalterns and 30 men of the 85th Line Regiment were taken prisoner.

"The rapid withdrawal of the enemy on the village of Hassenhausen, in which they threw away their muskets, backpacks, bags and hats, was quite common at this point . . ."

This would appear to be a similar confrontation to that of Regiment No. 59 with the troops facing each other in line and deciding the matter with a number of volleys. This action was won by the Prussians who put the French to flight.

Now to Jena and the report of Infanty Regiment No. 32:

- "However, the enemy now undertook an attack with force on the Grenadier Battalions von Sack and von Hahn to our right and at the same time on our right flank with a vanguard of a very impressive number of light troops supported by a strong infantry column behind them. I attempted to beat off this attack with several battalion volleys and we held off the enemy for a reasonable time and certainly caused him appreciable losses."

Here we have mention of the 'traditional' French column covered by skirmishers. It does not produce the shattering, battle-winning results which some historians attach to it, instead, despite the presence of a large force of skirmishers, the Prussian volleys keep it at bay for some time.

French Method of Tactical Victory

I am not claiming to present a comprehensive outline of the French tactics in 1806, all I am doing is mentioning a tiny number of incidents which gave a vague impressions of some aspects of French tactics. It should also be clear by now that I am not a supporter of the school of thought which attributes the French victory to their "tactical superiority".

First, to the report of Colonel von Eisner, commander of the Infantry Regiment Duke of Brunswick No. 21:

- "There was no mention of disposition, position of the enemy, knowledge of the terrain. There were great gaps between the battalions and regiments . . ."

Here we have an indication of the faulty Prussian staff work which also affected tactical matters. Ignorance of the locality and whereabouts of the enemy could easily facilitate tactical surprise. By leaving such noticeable gaps between the formations, the Prussians were encouraging flanking movements by the French. Von Elsner continues:

- "I pulled back onto the battalions in part forced back and partly to those advancing one by one on my left and now participated in all the unfortunately isolated, totally unsupported attacks which were undertaken without any ultimate objective and co-ordination and as a consequence unsuccessful . . ."

Again, a lack of co-ordination at higher levels of command reduced the enthusiam of the Prussian infantry in dissipated attacks. The confusion which may have been apparent in the Prussian battalions was more likely to have been caused by their own faulty staff work and command system than by the actions of the French.

In fact, one could say that it was not so much a case of the French winning the Battles of Jena and Auerstaedt, as of the Prussians losing them. Von Eisner continues:

- "The whole battalion was burning with eagerness to get stick into the enemy, but in every advance, we were left on our own by the neighboring battalions. Thus we undertook several attacks and at the moment of the bayonets attack, denied all support, we had to fall back, this always occured calmly and in good order although accompanied by a murderous fire . . ."

We see here that the Prussians were burning themselves up in these unco-ordinated attacks. In the meantime, the hard-pressed French were biding their time, conserving their reserves to counter-attack the exhausted Prussians at the right moment:

- "During this, the enemy was continually extending his left flank, forming more squares, the last on the right flank of the battalion. I had to make the first quarter wheel to th rear and

advanced on this square too, but on our own, success was not possible and we remained alone in our endevours . . . ."

Then came the counter-attack:

- "On top of that, I was alone on the right flank and especially as a lot of cavalry was to be

seen here, there was a general feeling that we would be surrounded, so the possible defence of a deep defile on the right flank was now the first of my duties. I fell back to the village of Rebhausen and remained there until the retreat was ordered . . ."

The Prussians here were outmanoeuvred by the French, and in particular by their cavalry, there is no mention of the use of skirmishers and columns. For the fate of Infantry Regiment No. 28, we shall again refer to the report of its commander:

At right: JAEGER 1806 (left).

At right: JAEGER 1806 (left).

Source: Kostuemeder Gansen Preussischen Armee by W. Henschel (Berlin 1806) , and,

JAEGER OFFICER 1806 (left).

Source: Henschel.

- "Hardly had the 2nd Battalion marched off when the enemy re-inforced his right flank with cavalry and with them he attacked our battery which was standing in a more isolated position from when the 2nd Battalion had marched off. They attacked with such impetuosity that they even came up to the left flank and rear of the 1st Battalion in such a way that we had to fire to the front, to the rear and to the side .... Meanwhile, the enemy detached a lot of cavalry to go around our left flank, at first in wide wheels and then gradually in ever smaller ones .... At about this time, our large cavalry attack failed and from this moment on, our situation on the left flank began to get critical The enemy opposite our brigade continually brought up re-inforcements, there was no more to be seen of our weak cavalry, and this resulted in the brigade commander seeing it necessary to form battalion square with his brigade, which was done with the exception of the 2nd Battation and von Alvensleben's detachment... Whereupon the battery reported that it had completely run out of ammunition and the brigade commander ordered that it should go to the reserve for the time being.

The right flank was, in the meantime, already beaten and in the process of withdrawal. The enemy charged the three squares; the two of the Regiment Schimonski wavered; the square of the 1st Battalion von Malschitzky, where I was, beat off the charge ...."

A combination of outflanking by cavalry and a frontal attack by infantry succeeded in forcing Infantry Regiment No. 28 to retreat. The lack of cavalry to protect the Prussian flank would seem to be the cause of this defeat and not the "tactical superiority" of the French battalions.

Now to Jena and Kalckreuth's report again:

- "Also, the movements of the enemy cavalry which were beginning to go around our completely unprotected right flank, thus coming on our rear, were drawing the men's attention and thereby causing a degree of despondency. The officers had to devote all their powers to raise their spirits and order was maintained. However, the enemy now undertook a strong attack on the Grenadier Battalions von Sack and von Hahn on our right and simultaneously on the right flank of the regiment with a vanguard of a very appreciable number of light troops backed up by a strong infantry column ...."

The inevitable occurred - outflanked and attacked in the rear by cavalry and charged frontally, the regiment broke. It is clear that the French victory in this incident was not due to the column formation of the infantry, but due to a combination of events. It would have made little difference to the outcome if the French had been in line or any other formation, come to that as the Prussians were already defeated and demoralised by the cavalry before the infantry pressed home.

From all the above, we can glean an outline of French tactics in 1806. Initially, they would allow the Prussians to attack, wearing them down with musketry and cannister fire, often in a desperate defence. Meanwhile the reserves would move up, supporting the defence and extending the line so that it could move against the Prussian flank. The cavalry would then move around an exposed flank and threaten the rear of the exhausted Prussians who were by now often short or completely out of ammunition. When it was clear that the Prussians were wavering and would offer little, if any resistance, then the columns backed up by skirmishers would then move in, bringing the counter-attack to a successful conclusion. It was therefore not a question of formation which decided the issue but a question of timing.

Lastly, we can also analyse the faults in the Prussian tactics in 1806 as follows:

- 1. A failure to co-ordinate attacks at a regimental, brigade and divisional level.

2. A failure to support these attacks properly with cavalry and artillery.

3. A tendency to leave flanks exposed to enemy counterattacks.

4. An insufficient number of light troops with the line formations.

It was therefore not a question of formation which decided the issue on the Prussian side but a question of organization and staff work.

The remainder of this essay will be devoted to examining the post-Jena reforms with special reference to their effects on infantry tactics.

More Prussian Infantry

-

Part 1: End of Frederick The Great's Reign to the Campaign of 1806

Part 2: Tactical Aspects of the 1806 Campaign

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. III #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com