THE SPANISH

The early 16th century was an age when gunpowder and firearms were in their infancy and their best tactical use was yet to come. The Spaniards, Swiss and Germans used arquebusiers, but the French and Italians carried on with the old crossbow. French supremacy, achieved at the end of the 15th century, in the use of artillery was superseded by the proficient handling of hand-held firearms by Spanish infantry -- the Spaniards being consistently ahead of other nations in the development and employment of infantry small-arms.

Besides stimulating the progressive importance of firearms, the Spaniards realised the value of field entrenchments as a defence against attack, particularly by cavalry, and the Spanish General Gonsalvo de Cordova was perhaps the first commander to make decisive use of both tactics. At Pavia in 1525, when both sides were well entrenched, the Imperialists turning the French position by a night march and being victorious through their arquebusiers decimating the French cavalry. After Pavia, important pitched battles became rare.

Warfare in the 16th century involved some outstanding and remarkable military forces, such as the French gendarmerie of the Compagnies d'Ordonnance; the trained mercenary bands of the Condottieri, prominent in Italy since the 14th century; the Swiss phalanx of pikemen who had already established a reputation against the armies of Burgundy; the German landsknechts their imitators, raised and trained by the Emperor Maximitlian in direct opposition to the Swiss; the Light Horse genitors of Spain, who owed much of their tactics to wars against the Moors.

The perplexed commanders of this period had to find answers for such complicated problems as the combined use of heavy and light cavalry, the tactical employment of pikemen, both in conjunction with musketeers and when confronted by them; and the best use of large and small field artillery.

The manner of warfare itself was changing and it became perhaps slightly less creditable to win a pitched battle than to achieve success by manoeuvre, or by cutting the enemy's line of communications, by starving him out or distracting him by the sudden movement of troops to an unguarded front. Generals who had not suffered disaster were equally esteemed with those who had won positive successes.

The French and Dutch Wars of Religion in the late half of the century were notable for the manner in which generals waited to see how the balance of forces might change, often neglecting tactical advantages in the hope that a few more weeks of physical and financial starvation would bankrupt their enemy and so make battle unnecessary. Commanding generals were thus placed in a difficult position, never knowing when their armies were going to melt away; if morale was low or pay in arrears then a commander tended to manoueuvre cautiously and avoid decisions.

The Spaniards' early proficiency in the use of hand firearms, coupled with de Cordova's method of entrenching his armies, was in effect a throwback to the successful English longbow tactics, with the enemy obligingly attacking them in good defensive positions. The Spanish sword-and-buckler men employed highly successful methods of running in under pikes, particularly when locked in a frontal clash, so that their short stabbing sword was most effective in a jammed formation.

There are numerous recorded instances of the Spanish sword-and-buckler men, with arquebusiers, slaughtering Landsknechts, French infantry and even the Swiss.

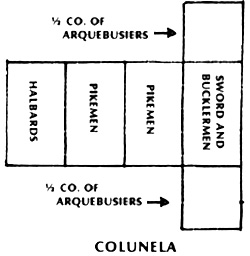

In 1505, the Spanish evolved the COLUNELA, the firstever tactical formation based on the mutual employment of fire-and-shock weapons and the forerunner of the modern battalion and regiment. It consisted of 5 Companyies (about 1000 to 1,250 men) of mixed pikemen, halberdiers, arquebusers, with sword-andbuckler men; it was required because the swordsmen, who could cut-up the enemy pike formations, needed protection from cavalry by arquebusiers and pikemen.

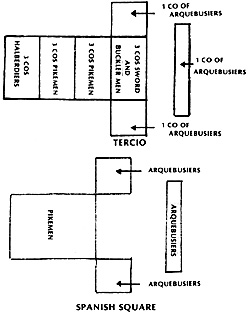

Later, the Spanish gradually developed the TERCIO, a

large organization of 3 Colunelas, totalling 3,000 men, with

its own fixed chain-of-command and strong enough to fight

independent actions. Made up of pikemen and

arquebusiers, the basic fighting units of the army, as the

tercio became standardised, they formed the SPANISH

SQUARE where the proportion of arquebusiers to pikeman

was increased and they were intermixed in several ranks

with the pike formations. When firing, the front rank men retired to re-load while those behind moved forward so that a steady fire was maintained; the pikes bore the brunt of both offensive and defensive shock action.

Later, the Spanish gradually developed the TERCIO, a

large organization of 3 Colunelas, totalling 3,000 men, with

its own fixed chain-of-command and strong enough to fight

independent actions. Made up of pikemen and

arquebusiers, the basic fighting units of the army, as the

tercio became standardised, they formed the SPANISH

SQUARE where the proportion of arquebusiers to pikeman

was increased and they were intermixed in several ranks

with the pike formations. When firing, the front rank men retired to re-load while those behind moved forward so that a steady fire was maintained; the pikes bore the brunt of both offensive and defensive shock action.

At right, a Colunela: A tactical grouping of five companies equivalent to the modern bat talion, consisting of 1000-1250 men arrayed as shown.

Towards the end of the 16th century, the introduction of the musket increased the firepower of these formations, and enabled the lighter, more mobile arquebusiers to take on a skirmishing role. The Spanish tercios reigned for some 150 years and were not really discarded until the Battle of Rocroi in 1643 ended their supremacy.

At right, a Tercio: A larger formation than the Colunela, standardized to consist of

three COLUNELAS, roughly 3000 men, deployed as shown. Underneath, a Spanish Square:

A late improved version of the TERCIO consisting exclusively of pikemen and arquebusiers.

At right, a Tercio: A larger formation than the Colunela, standardized to consist of

three COLUNELAS, roughly 3000 men, deployed as shown. Underneath, a Spanish Square:

A late improved version of the TERCIO consisting exclusively of pikemen and arquebusiers.

Later, the Spanish superseded light horse by mounted arquebusiers and herreruelos, with a shorter firearm which could be used from the saddle; their foot regiments became smaller than the immense tercios of earlier wars. The combination of pike and firearms continued, as it did in other European armies, far into the 17th century and their heavy cavalry, always relatively few in number, continued to use the lance long after it had been abandoned in other armies.

THE SWISS

One of the biggest military problems that taxed the minds of generals in the late 15th and early 16th centuries was how to counter or imitate the warlike efficiency of the remorseless phalanx of mercenary Swiss pikemen, whose steamroller-like advance struck terror into the hearts of their enemies and flattened every army that dared to stand in their way.

No French army of the 16th century went forth without a large Swiss contingent who, throughout their notable history, were mercenary to the foremost degree, selling military aid to the highest bidder and immediately withdrawing it when cash ran short; nor would they fight against other Swiss.

Mercenaries, employed by most countries during the 16th century, were professional soldiers highly proficient with their own particular weapons, but sometimes badly disciplined troops who deserted without scruple, considering that they owed no loyalty except to their own immediate leader. The most effective of all mercenaries were the Swiss pikemen who, in their heyday, aroused such a sense of terror in their opponents that the wargamer should consider whether to build into the framework of his rules a "Ferocity Factor" and even a "Treachery Factor" (as described in the book Wargames Through the Ages -- Vol. I by D. Featherstone).

These redoubtable mercenaries had the habit of marching off in complete corps if they felt that their pay was in arrears or they were not bound by their contract, as at Pavia when 6,000 Swiss went off a few days before the battle, even though they were paid up to date! Biggest employers of the Swiss, this particularly affected the French. Mercenaries acted in this characteristic manner right down to the Thirty Years War in the next century, when Gustavus Adolphus and Wallenstein enlisted deserters wholesale.

Frequently serving under the banner of their Canton the Swiss also displayed local "town" banners in their columns. They never worked under a commander-in-chief, but under a committee of captains; there is no instance of a Swiss officer ever rising to be a capable general -- their formations seemed to have been run by old "sergeant-majors"!

Nevertheless, these old "captains" showed considerable skill in all the arts of warfare including surprise, ambush, forced marches and other tactical manoeuvres. They had a strong feeling of pride in their formations and any man who showed signs of panic was handed over to the hangman as soon as convenient. Stubbornly resisting to the last man even when defeat was certain, when the vastly diminished numbers march ed from the field with closed ranks, never dispersing or being routed. Because of their ruthlessness in battle, rarely taking prisoners, they received similar treatment from the enemy who had old scores to pay off.

In the open field the Swiss were invincible, both against infantry and cavalry so, as time went on, generals formed up their troops in positions which were as unlike an open field as possible. Undergrowth, rocks, undulating ground or any other terrain that might upset the cohesion of their phalanx was of the greatest tactical importance, because Swiss success depended on their close formation and, when gapped, the enemy, such as the Spanish sword and buckler men, could slip in between the divided ranks with short swords.

Commanders learned in time that when they had to face a Swiss force of three columns in echelon, with the right leading, the simplest tactic was to lure it on to attack an entrenched position, strong with artillery and arquebusiers backed by pikemen. Or to make a flank attack on the leading column with cavalry or light troops, forcing it to halt as it beat off the assault because, if the flanks of the pikes had to come down to resist a charge, the pikes in front had to stop otherwise the column would break in two.

The close formation of the Swiss columns make them extremely vulnerable to artillery and, formidable soldiers as they were, the Swiss never recovered from their first notable checks at Marignano in 1515 and at Bicocca in 1522. The Swiss had no cavalry of their own but after Bicocca their three regulation phalanxes of pikemen usually had on their flanks men bearing firearns (sometimes as many as 1 in 5 or 6) who were not part of the striking force, but covered the flanks of the column or went out in front to skirmish before the charge began. Their very small numbers of cannon never accomplished any recorded success.

THE GERMANS

The Landsknechts, those colorful substitutes to the Swiss, were far from equal to the genuine article and invariably seemed to have been swept away with the bloodiest losses whenever they met the Swiss. These German mercenaries fought in most armies of this period and were no more reliable than the Swiss. Seemingly indifferent to any national emotion, the only general feeling, other than pay, that affected the Landsknecht was his overweening hatred of the Swiss, who reciprocated the emotion and when they met in battle neither ever gave quarter to the other.

In the 16th century, the Landsknechts drifted everywhere, being found in the French service and in Poland, Sweden and Denmark -- there was even a band of them in England, employed by Protector Somerset to put down Kett's Norfold rebellion in 1549.

It is said that the Landsknechts held the pike very low down and always kept the point slanted somewhat upwards, while the Swiss grasped the weapon nearer its middle and kept the point down which, when the staves were crossed, gave them a great advantage in push-of-pike.

When two pike columns clashed, the men whose points were held high were likely to find them pushed up above the heads of the enemy while those whose points were down would get a better chance of burying them in the body of an opposing enemy. Landsknecht company's were always accompanied by a proportion of men armed with handguns.

Both the Swiss and the German Landsknechts only employed the very best men to trail their pikes and the "doppelsoldner" (soldiers with extra pay who fought in the front ranks) were formidable veterans.

Early in the Pike-and-Shot period, massed phalanxes of pikemen, particulary the Swiss, could sweep both infantry and even heavily armoured cavalry from the field. When pike phalanxes met there was a "push-of-pike" and at the first impact, most ot the front ranks of both sides usually went down, so that masses of bodies checked all forward movement on both sides, forcing them to stand locked in a "push-of-war".

Astute commanders placed one rank of arquebusiers or pistoleers between the first and second ranks of pike formation, to hold their fire until a moment before the clash when they blazed away to bring down the front rank of the enemy -- the officers and picked men. This had its snags because the firearmed men had to re-load or else they were completely helpless if the pike rank behind then continued to move forward; being jammed between two ranks of their own pikes they could not escape, and they must have greatly inconvenienced the pikemen, preventing them from fighting in ther usual manner. It must have been interesting when both commanders had the same idea of this method of using arquebusiers!

In time, the vast formations of pikes were substituted by smaller corps with pikes and arquebus blended together, both acting on certain fixed principles.

Attempts were made to combat pike formations by furnishing cavalry with pistols so that they could caracole and force gaps in the serried ranks of the pikemen. But caracoling had to be a very precise business and only veteran troops could maintain their order after the first few firings. Defensive tactics against the caracole were either to charge the column of pistoleers with other cavalry or else to have arquebusiers mingled with the pikemen who could shoot down the front rank of the pistoleers before they could come close enough to do much damage, as the arquebus could out-range the pistol.

More Pike and Shot

-

Pike and Shot Period: Introduction

Pike and Shot Period: Spanish, Swiss, Germans

Pike and Shot Period: Italians, French, Swedes

Pike and Shot Period: English Civil War

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. III #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1981 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com