The battle of Maida, fought on the plains of the Lomatb River in Italy in 1806, foreshadowed every engagement between the French and British during the Napoleonic Wars. The battle demonstrated the tactical superiority of the British infantry that underlay Wellington's triumphs in the Peninsula and at Waterloo. Without strategic or political significance, little noticed by most of Europe in its own time, Maida provides a clear picture of a British versus French Napoleonic battle that should be of interest to both the historian and the wargamer.

THE HISTORICAL BATTLE

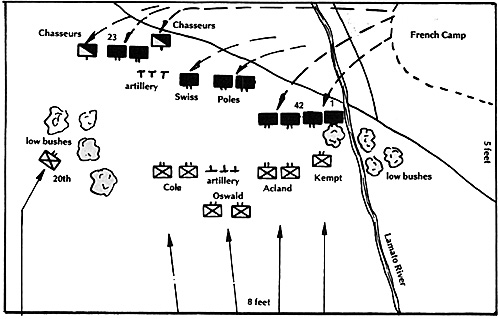

The British expeditionary force that fought at Maida totaled 5,196 men. Under the command of Sir John Stuart, the army formed into four weak infantry brigades of two battalions each. (See order of battle on map.) Lacking cavalry entirely, the infantry received support from three field guns. Stuart's mission after landing in Italy involved harrassment of the French and support of the local Calabrian guerrillas. Marching at dawn of July 4, Stuart advanced to attack an intercepting French army that he believed to comprise 3,000 men.

In reaction to the British landing, the local French commander, General J ean Renyier, rapidly gathered a small army. Boasting that "five thousand men were enough to thrust 6,000 or 7,000 English into the water"

Renyier advanced upon the invaders. His field force comprised six French, two Polish, and one Swiss battalion of infantry, three squadrons of cavalry, and four field guns with a combined strength of 5,679. Displaying the amazing marching power that had dazzled Europe, the French marched 80 miles in three days to the vicinity of Maida.

On the night before the battle the French encamped facing north on heights overlooking the Lomato River. (See map.) Since Renyier had to turn westward to meet the oncoming British, he began his maneuvers on the day of the battle by changing front to the left. This change of front resulted in an echelon formation with the veteran 1st Legere and 42nd Ligne in advance. Similarly the British had one wing advanced; that comprising Kempt's converged light brigade. Thus the first clash would see the meeting of these elite units.

Actually the first combat of some tactical interest occurred in the low bushes on the British right. Kempt with seven British light companies in line, covered his right with a detachment of 250 Corsican and Sicilian marksmen. As they entered the bushes, two companies of French voltigeurs, detached from the 1st Legere, attacked. Receiving a sudden surprise volley, the Corsicans broke and ran. The confusion spread to the Light Brigade as the captain of the right flank company from the 20th was killed. Kempt promptly detached two companies to counterattack into the bushes. Aided by the rallying Corsicans, this counterattack succeeded. The right flank stabilized, the two British companies doubled back to join their unit. They arrived just as the dust cleared, the French cavalry vedettes fell back, and the advancing French columns were spotted.

In what Oman calls "the fairest fight between column and line that had been seen since the Napoleonic Wars began", two heavy battalion columns of 800 men each advanced on the light battalion. Deployed in parallel columns of companies, 60 men wide and 14 ranks deep, the 1st Legere relied on tactics that had proven successful against the Austrians. Spread over a 350 yard front, the 700 British light infantry waited in two deep line.

Fire

The British delivered a long range volley at 115 yards. Noting the resultant wavering of his men, the French Brigadier Compere urged his men onward. A second even more telling volley struck the 1st Legere at 80 yards. Still the gallant French advanced. Now at a point blank 30-yard range Kempt spoke: "Steady light infantry, wait for the word. Let them come close." The third volley punished the French terribly.

By now almost 900 men had fallen while Kempt had suffered barely 50 casualties. The light infantry followed up the third volley with a charge. Unable to withstand the pressure, the 1st Legere broke and ran. This action was the key to the battle. The best French troops had advanced in the prescribed style and had been decisively defeated by the best British troops fighting as their tactical doctrine dictated.

As the 1st Legere broke, the 42nd Ligne came into contact with Acland's brigade. Advancing parallel and to the rear of the 1st Legere, the 42nd was apparently demoralized by the rout of the Legere. Acland's brigade fired two volleys at long range and this was enough to rout the 42nd. Acland pursued the fleeing French until he met Peyri's foreign brigade.

The two Polish battalions broke at first contact. (It should be noted that these troops were mercenaries fighting for the French Kingdom of Italy and not the elite troops of the Duchy of Warsaw that were later to gain such renown.) However, the 1st Swiss battalion dealt the British a severe check. These Swiss were uniformed in their traditional red. The British 78th Regiment mistook them for de Watteville's Swiss Regiment in the British service. Consequently the 1st Swiss was able to advance to close range and discharge a destructive volley into the 78th. A ten minute fire fight ensued.

Having covered the withdrawal of the retreating French on this portion of the field the gallant 1st Swiss retreated. Acland's troops in turn were fought out. In gaining their success over the 42nd Ligne and the Swiss and Poles, Acland's troops suffered half the casualties that the British army lost during the entire day.

As will be recalled, because of the initial deployment of the two armies, the battle progressed sequentially toward the British left. Here Cole's brigade of the 27th and six converged grenadier companies came into action. Cole received support from the 58th and four companies of de Watteville's Swiss, as well as from three field guns. Facing these 2,200 men were 1,800 infantry of the 23rd Legere, 200 cavalry, and four guns.

Renyier deployed these troops on a slight rise. Unknown to the British, his intent was to fight a rear guard action to cover the retreat of his battered army. The artillery paired off in an unprofitable duel. Cole attempted to advance, but was constantly embarrassed by the French cavalry. These chasseurs feigned repeated charges thus forcing Cole to form square. Nevertheless, soon the infantry engaged in a frontal fire fight. The action bogged down with neither side gaining an advantage. The battle was brought to a sudden end by the unexpected advance of the recently arrived British 20th Regiment. This force landed independently of Stuart's main force and marched to the sound of the guns. The 20th appeared at an opportune time and place.

Finding himself on the flank of the French cavalry, Colonel Ross formed the 20th into line in some scrub bushes and discharged a volley at 50 yards range. The cavalry withdrew. Ross pressed his advantage by marching against the flank of the 23rd Legere. This advance decided the day. The French rearguard retired in order having successfully screened the retreat of their army. The British did not pursue. As one British participant said, " Had we owned 200 good cavalry we should have destroyed the whole of them. But we could do little more with our jaded infantry."

Casualties

Total French casualties for the two hour battle of Maida amounted to about 2,000 men. The British lost 327. The significance of the battle did not lay in the casualties inflicted, though by normal standards Stuart won a notable victory. Rather the battle demonstrated for any intelligent observer the superiority of the line over the column.

And it is important to recognize that on the British side intelligent observers were at hand. Cole, who later commanded the 4th division in the Peninsula; Colborne, who made the final attack against the Imperial Guard at Waterloo, and Ross, who served under Wellington and later gained fame as the captor of Washington in the War of 1812, were all present at Maida. These officers who observed this first typical clash between British and French went on to apply the same tactics on the battlefields of Spain and Portugal .

On June 14, 1808, two years after Maida, a diarist recorded Wellington as saying just before his departure to Portugal: "If all I hear about their [the French] system is true, I think it a false one against steady troops." I think it is reasonable speculation to infer that what Wellington had been "hearing" were accounts of the battle of Maida from Cole, Kempt, Oswald, Colborne, and Ross.

Regardless, two points are certain: Maida decisively confirmed the superiority of British linear tactics, and Wellington utilized the tactical blueprint of Maida as he repeatedly defeated French infantry attacks in the Peninsula and at Waterloo. Viewed in this light, Maida can be seen as an epic day in the history of the British army.

THE WARGAME

Fighting Maida as a wargame can be an entertaining and instructive experience. (In fact, if you attend ORIGINS '80 you can have the opportunity to do so.) The forces engaged were small. Therefore the table top general must carefully consider his tactics. Just as in the real battle the first contact can be decisive.

To help you reproduce Maida, I offer the following suggestions. Plan the battle to simulate no more than three hours of historical time. Set up the terrain as the map shows. Maida is well encompassed by an eight by five table. Begin the battle with the British entering the table from the south. The French start in their encampment on the hill in the northeast corner. The Lomato River is fordable but should impose a slight delay to cross. The low shrubs should restrict movement and fire effect.

A roster system can be made from the strengths pro vided on the order of battle. The morale column on the order of battle rates the morale of the units using the Napoleonic Generalship system. This system scales a unit's morale from one to twenty. A die roll equal to or under the morale level allows a unit to pass its morale test. Clearly a gamer can convert these ratings to whatever rule system he prefers. Both Renyier and Stuart were trying to destroy the opposing army. Therefore victory must be based on casualties.

Furthermore, neither army should be permitted to fight to the death. Just as Renyier fought a rearguard action after his main assault was defeated, so the table top general must withdraw when losses become prohibitive. I suggest the following: when losses equal 20% of the entire army the general secretly rolls a six sided die; a one or two means he has to withdraw.

For each successive 10% loss subtract one from the die and reroll. Finally, Ross's timely intervention must be considered. The British could not count on when or where the 20th Regiment would appear. To simulate this uncertainty use the following rolls from a six sided die: 1=does not arrive; 2=middle rear after one and one half hours, 3 and 4=frontline after two hours 5=middle frontline after two hours; and 6=right frontline after two hours.

With this information you should be ready to refight the battle of Maida. If you want a complete test of your generalship, organize your club or friends into sides and fight it out. The battle shouldn't take overly long. Then change sides. This way you will be challenged by a differing set of tactical requirements. If you win a complete victory fighting both sides then you have demonstrated a fine appreciation of Napoleonic small unit tactics.

ORDER OF BATTLE

| BRITISH ARMY | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BRIGADE | UNIT | STRENGTH | MORALE |

| Kempt's advanced guard | Light battalion Corsican

Rangers Volunteers of Sicily | 694 272 | 18 13 |

| Cole's 1st Brigade | 1/27 Grenadier battalion | 781 485 | 17 18 |

| Acland's 2nd Brigade | 2/78 1/81 |

738 603 | 16 17 |

| Oswald's 3rd Brigade: | 1/58 de Watteville's (20 regiment)* | 576 287 624 |

17 15 17 |

| FRENCH ARMY | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BRIGADE | UNIT | STRENGTH | MORALE |

| Brigade Compere: | 1 Legere 42 Ligne | 1,810 1,046 | 17 16 |

| Brigade Digonet | 23 Legere 1 Polonais | 1,266 937 | 16 14 |

| Brigade Peyri: | 1 Suisse 9 Chasseurs a cheval | 630 328 | 16 |

| * = unbrigaded | |||

Rebuttal: Letters to Editor v2n2 Response: Letters to Editor v2n6

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 1 #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1980 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com