The idea of a force of native levies, recruited from locals

who had no reason to love their northern neighbors, was

almost as old in Natal as the colony itself.

The idea of a force of native levies, recruited from locals

who had no reason to love their northern neighbors, was

almost as old in Natal as the colony itself.

In the 1820s the Zulu warrior king Shaka sent his impis against the clans then living south of the Tugela and Buffalo rivers. Nothing if not efficient, they smashed the token resistance of the stronger clans and sent them fleeing to the south, slaughtering those who lingered behind. When the first British settlers landed at Port Natal, they found the land despoiled, littered with human bones and razed kraals, the only inhabitants a few pathetic wretches living in caves and, as often as not, reduced to canabalism.

Gradually, however, they crept back, lured by the prospect of protection offered by the whites' growing political prestige. They were swelled, over the years, by a stream of refugees from over the river, fleeing from a series of internal Zulu upheavals. In the 1850s the steam swelled to a veritable flood as Mpande's rival sons, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi, squared up for a show-down. When civil war errupted in 1856 Mbuyazi's faction, the iziGqoza, fled for Natal. Most didn't make it, Cetshwayo catching and massacring them at the battle of 'Ndondakasuka, and those that did had little cause to love the new king over the river.

First Attempt

The first attempt to utilize this source of man-power for a military end came in 1838, when the British settlers at Natal raised an army to launch a foray into Southern Zululand. The idea was to take some of the pressure off the Voortrekkers, who were camped in a series of fortified positions on the foothills of the Drakensburg to the north, following the massacre of their leader, Piet Retief, and his followers by the Zulu king Dingane. Perhaps 3,000 strong, their warriors identified by strips of white calico around their heads, the 'Grand Army of Natal' marched proudly across the border, only to be confronted by, and after a rather intriguing engagement massacred by, a Zulu force before they had gone more than a few miles. As an omen, it was not an auspicious one, though one from which a lesson might have been learned.

By the mid-1870s there were more than 300,000 Bantu in Natal, a God-send to a harrased Lord Chelmsford, seeking to flesh out the European backbone of his army. The suggestion to raise a native contingent came from Anthony William Durnford, a Colonel in the Engineers who had done sterling work with native levies in a rebellion that had culminated in the battle at Bushman's Pass, where Durnford himself had lost the use of an arm.

Durnford had a plan carefully worked out, involving the mustering and equipping of 7,000 levies. Chelmsford snapped up the plan, but it was vetoed by the Colony's Lieutenant-Governor, who pointed out that the Europeans in the colony were outnumbered by nearly twenty to one. Should the Bantu decide to join the Zulus rather than fight them, a plan to arm and muster them could prove disasterous.

Since more Imperial troops were not forthcoming and something was needed, a compromise was reached. Three regiments were raised, the first of three battalions, the others of two, each of 1,000 men. There proved little enough problem in finding volunteers. The iziGqoza turned out in force, and were brigaded under their tribal inDunas. Others of Mpande's extensive progeny, chased out by Cetshwayo, lent their support, anxious to see their old rival suffer. Mkungo declined to take to the field himself, but loaned his followers; his half-brother uSikhota had no such qualms and was with his men on campaign until Isandhlwana dampened his enthusiasm.

Lost Opportunity

Sadly, much was not made of this willing material. Durnford had planned to uniform his men, officer them with regulars and arm them with rifles. There was no money for a uniform, only a few Imperial officers to spare, and certainly not the political support to arm the warriors.

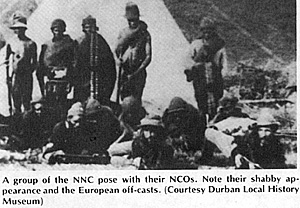

At right, a group of the NNC pose with their NCOs. Note their shabby

appearance and the European cast-offs. (Courtesy Durban Local

History Museum)

At right, a group of the NNC pose with their NCOs. Note their shabby

appearance and the European cast-offs. (Courtesy Durban Local

History Museum)

Only one in ten were given guns, with only five rounds of ammunition which were not replaced when target practice expended them. Most ot the European volunteers of any worth had enlisted in the mounted units, and only the dregs remained for NCOs. The warriors were given a red rag as a means of distinguishing themselves from the enemy, and a blanket Photographs and engravings reveal them to have turned out in a variety of bizarre European oddments; woolen caps, old jackets, top hats, with blankets worn en banderole.

They came with their own weapons, shields, spears and knobkerries with no semblance of uniformity. Their NCOs wore dark tunics, probably blue, with elementary braiding, light trousers and a slouched hat with a red pugree twisted round it. According to Colonel Henry Harford, who served with them with some distinction, the companies were further identified by small flags which bore the company number and a simple device approximating the natives' name for themselves; ingulube -- ' the pigs", for example, or izinkuzana -- the young bulls".

Durnford's experience in the Bushman's Pass affair had shown that native levies, treated as brave men and true soldiers, responded in kind. In 1879 the Natal Native Contingent was treated like dirt, and behaved accordingly. Where they might have served well as supports or scouts, they were herded like sheep, left in impossible positions or simply forgotten. Their NCOs, for the most part, bullied and cursed them and were the first to duck when the bullets started flying. The warriors, when confronted with their traditional enemy, simply ran away. Though recent research has cleared them of some of the blame for the disaster at Isandlwana, their overall showing throughout the war was little short of abysmal.

The native horse fared a little better, Durnford's prestige was high on account of his performance at Bushman's Pass, and several clan chiefs were prompted to turn out in response to his personal charisma. They came in small detachments, mounted on scrawny ponies; Hlubi of the baTlokwa with his followers, Sikali with 150 of his, Mafunzi with 75, Jantsi with 50 and the Edendale mission with over 100. Being Christian converts, the Edendale men regarded themselves as a cut above the others, and turned up with Khaki uniforms, boots and spurs, all provided at their own expense.

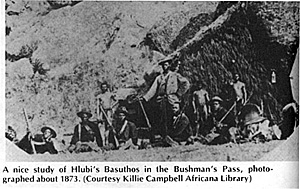

At right, a nice study of Hlubi's Basuthos in the Bushman's Pass, photographed about 1873. (Courtesy Killie Campbell Africana Library)

At right, a nice study of Hlubi's Basuthos in the Bushman's Pass, photographed about 1873. (Courtesy Killie Campbell Africana Library)

Their heathen bretheren were less smart; a photograph of Hlubi's men in Bushman's Pass shows them. wearing a variety of European off casts, mostly dark, and distinguished by a red rag or a pugree around slouch hats. A painting by Orlando Norrie shows them wearing blue shirts, barefooted, with assegais carried in a quiver on their backs.

The native Horse provided excellent service throughout the war, superb scouts and tenacious skirmishers. The stand of the Edendale men, covering the rout at Isandhlwana, is a remainder of what might, perhaps, what have been made of the NNC.

Augmented

In addition to the Natal natives, the British force was augmented by numerous 'outsiders'. In the troubled northern borders of Natal, where the Transvaal/Natal/Zulu/Swazi borders merged, the Swazi were more than a little involved in the affairs of their Zulu neighbors. Traditional enemies, the Swazi were more than eager to turn out at the prospect of furthering a few blood feuds, some looting and some pillaging, so a sizable number enlisted with Wood's Irregulars.

The Swazis are related to the Zulus; though their history is less bloody (survival by bending with the wind rather than through blatant expansionism) reports of them in 1879 reveal them to be every bit as pugnacious and arrogant as their more celebrated foes. Like the Zulus they were armed with antiquated guns, assegais and shields; rounder shields than the Zulus, with the pole standing out further at each end, with a small tuft of fur mid way up the top part of the pole. They wore similar arrangements of feathers and furs to the Zulus but with gaily coloured cloth skirts in place of the fur umTsha.

Finally, there were those Zulus who came over to the British as the campaign progressed. Many inDunas, particularly in those areas distant from the royal kraal at Ulundi, finding their young men away with the regiments and the enemy on their doorstep, found it suddenly expedient to change sides. Prime amongest these was uHamu, Cetshwayo's half brother, who had quarreled with him before the war and retreated to his estates with a large number of warriors from the uThulwana regiment.

These defected to join Wood's column, and went into action at Hlobane, some apparently wearing the uniform of their old regiment. Their betrayal of king and country dampened their fighting spirit, however, and when the attack on Hlobane dissolved into bloody fiasco, most slipped away.

Generally, the history of the native forces of Natal is one of missed opportunities and lessons that no one bothered to learn. When Natal again called out her troops in the Bambatha Rebellion in 1906, she was to come up against the same problems again and again.

Though the overall showing in the war was poor, the wargamer should not be tempted to leave out a force of NNC. Through accident or design, they played a significant part in several actions, and it would be historically inaccurate to ignore them. The Native Horse are more than worthy of being represented and, provided they are handled correctly, should prove a credit to any tabletop army.

SOURCES

Much of the pedestrian history of the NNC can be found in the Zulu War bible: Donald R. Morris' The Washing of the Spears. Colonel Henry Harford's journal, recently published by Shuter and Shooter (Gray's Inn, 230 Church Street, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa), contains superb eyewitness accounts of the NNC at rest and play. Uniform detail can be gleaned from contemporary photos and engravings.

Related

-

Zulu Firepower

Zulu Army Organization

Zulu Weapons and Uniforms

Native Levies in the Zulu War

Imperial Infantry Uniforms of the Zulu War

Zulu Roundup: Figures and Books

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 1 #4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com