In the mid-17th century, unrest in the steppes of Ukraine was on the rise. The Polish-Lithuanian empire dominated an area from Warsaw to Moscow, and the Ukrainians were tired of their exploitation and abuse.

In the mid-17th century, unrest in the steppes of Ukraine was on the rise. The Polish-Lithuanian empire dominated an area from Warsaw to Moscow, and the Ukrainians were tired of their exploitation and abuse.

At right, a Zaporozhian Cossack as depicted on an old postcard.

At the little town of Korsun, virtually in the middle of nowhere, an army of Zaporozhian Cossacks supported by Crimean Tartars overwhelmed a Polish army sent to crush them, and started a revolutionary fire that would sweep across the steppes and make Ukraine a nation.

Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks were not your typical disorganized horde or “cannon fodder” as described during Napoleon’s time. These Cossacks were defined by their horsemanship, proficiency with the saber and their level of organization during time of oppression. An analogy could be made between the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the American Indians. They knew the terrain, and how to use it to ambush or evade their enemies.

The Zaporozhian Cossacks were not your typical disorganized horde or “cannon fodder” as described during Napoleon’s time. These Cossacks were defined by their horsemanship, proficiency with the saber and their level of organization during time of oppression. An analogy could be made between the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the American Indians. They knew the terrain, and how to use it to ambush or evade their enemies.

Reenactor images from webpage: http://artiom.home.mindspring.com/cossacks/sech.htm

They were very religious in there belief in God. The Zaporozhian’s were known for their exceptional honesty. “According to the Catholic priest Kitovich, in the Zaporozhian Sich (meaning-“clearing beyond the rapids”) one could leave his money out in the street, not worrying that it would be stolen". [1]

With this reputation, it’s not surprising that the Polish crown hired them to maintain order within the vast open spaces of the Ukrainian steppes.

Weaponry

So, purchases of such magnitude would typically be done by other means such as gold, food or trade of nobleman from raids. It would be very difficult to herd some 4,500 cattle to a stronghold for an exchange of 10 cannons and munitions.

The dress of the Zaporozhian’s was light. To keep cool during hot summer days loose baggy pants were worn. They were colorful varying from red, blue, black, or yellow. They were matched with an off white loose shirt over top. At times a vest or light jacket accompanied the look. This was complimented with a large sash around their waist. The sash color typically depicted a rank within the Cossack order, with black being the most common and red being one of nobility or stature within the group. This light clothing made the Cossacks very agile when in combat or conducting duels. The Cossack’s would shave their heads only leaving a long lock of hair to one side depicting the brotherhood of the Zaporozhian’s and dawning of the long burly moustache. A symbol to which today distinguishes the true Zaporozhian Cossack from other Cossacks.

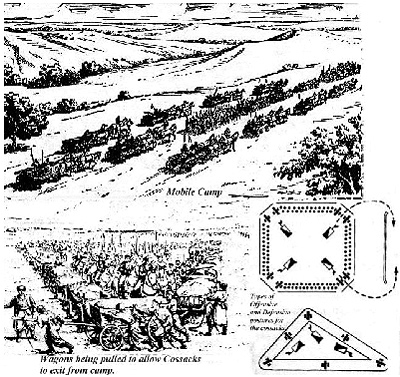

Mobile Camp

The Cossack army typically fought with their men in a mass, formed around a unit called a mobile camp. Zaporozhians would fight by surrounding themselves with a moving perimeter of wagons. At every other wagon a small cannon was positioned for support. The cannons were not only small but could be moved around quickly and easily to other wagons.

Within the mobile camp were the Cossack foot soldier armed with musket, pike or swords. Mobile reserves were formed from the different groups of cavalry armed with sword, lance or pistol. The way the Cossack mobile camp would operate is that the entire camp would move in unison. They would approach their enemy, using the wagons as both a shield and to move the artillery closer to fire as opportunities presented themselves.

As the mobile camp moved closer to a charge range, certain wagons would be pulled away and the cavalry and/or foot would then proceed to attack. If the attack was unfavorable to the Cossacks they would simply retreat back into the mobile camp and the wagons would close its doors like a fort. The Cossacks would then immediately take up a defensive position against an approaching enemy, unleashing a hail of cannon and musket fire. If the enemy retreated, then the wagons can be pulled away at any point within the perimeter and another attack could be launched.

The Polish army had numerous functions throughout the steppes such as squashing local rebellions, escorting nobility and guarding caravans between regions. Polish domination became very harsh and punishment came quickly. It was not uncommon for peasants to be slain or beaten. To appease such concerns to local nobility in Ukraine the Polish crown would hire Cossacks as mercenaries and attach them to their army. They were given the task to help the Poles in maintaining order throughout the steppes. These were known as registered Cossacks. Allowing the presence of Cossacks ensured some stability. Registered Cossacks were not only paid but had an opportunity to own land and be given recognition when retired from service.

Czaplitski and Khmelnitsky

Bohdan Khmelnitsky, a young lieutenant was a wealthy landowner who kept to himself. However, he was not isolated against the harsh Polish rule under the local regent, Czaplitski. In a retaliatory raid, the regent ordered his troops to retaliate against recent Cossack raids within the area and punish several local peasants by burning their homes and taking their livestock. However, the raid fell upon Bohdan Khmelnitsky’s land. Czaplitski’s troops burned his farm, killed his son, and abducted his wife. Khmelnitsky sought justice through the Polish government’s courts but his claims were rebuked and rejected. He escaped and found refuge in the Zaporozhian Sich along the Dnepro River, soon learning the ways of the Cossack.

“The basis of authority in Zaporozhye was peace, and fellowship among Cossacks. When there was a need to solve some important issues, kettledrums summoned all the Cossacks to the Sich square, where a Rada (Council) or the Host Council would take place. During Rada every Cossack, regardless of his rank or means, could openly tell his opinion and had a right to vote. But after the decision was taken by the majority of votes, every Zaporozhian and all the hosting generals had to abide by it.” [2]

Thus through the Rada, Khmelnitsky became the Hetman of the Cossacks. He successfully rallied for Cossack support in 1647 and raised an army of over 20,000 Cossacks. His cause was not only for revenge but also for the social and religious persecutions of all Cossacks. His political savvy even won him favor with the Crimean Khan, Tuhai-Bey, when he convinced Tuhai-Bey that the Poles were going to attack and force the Tatars out of the Crimea. Khmelnitsky would send the Khan gifts of wine, mead, gold, and cattle to persuade Tuhai-Bey to become an ally. Not that it was difficult, for Tuhai-Bey shared Khmelnitsky's dislike of the Polish crown. The Khan eventually gathered over 20,000 Tatars to support the Zaporzhians. The movements, numbers, and battles to follow would catch the Polish Crown by surprise.

Battle at Korsun: May 26-27, 1648 The Zaporozhian Cossacks

The weaponry of the Zaporozhian’s consisted of mainly muskets, swords and knives--often acquired from raids on traveling caravans between the Tatars and Turks or between Polish regions. The Zaporozhian musket did not have a bayonet, so a five-foot lance was also carried. Cannons were of small caliber and portable enough that they can be carried by horses within the army. Both wheels and the cannon itself could be easily mounted on the backs of horses and carried to battle with ease. The typical cannon in those days would cost the Zaporozhian Cossack 442 head of cattle and one cannon ball with powder a mere 9 heads of cattle.

The weaponry of the Zaporozhian’s consisted of mainly muskets, swords and knives--often acquired from raids on traveling caravans between the Tatars and Turks or between Polish regions. The Zaporozhian musket did not have a bayonet, so a five-foot lance was also carried. Cannons were of small caliber and portable enough that they can be carried by horses within the army. Both wheels and the cannon itself could be easily mounted on the backs of horses and carried to battle with ease. The typical cannon in those days would cost the Zaporozhian Cossack 442 head of cattle and one cannon ball with powder a mere 9 heads of cattle.

Cossack Mobile camp.

Cossack Mobile camp.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 91

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com