If You Go Down To The Woods Today

If You Go Down To The Woods Today

With enemies pushing at almost every border, the fourth century AD was a time of almost continual crisis for the Roman Empire. Constantius, the Emperor, recognised that the situation was too much for one man to handle and appointed Julian, his cousin and only remaining male descendant of Constantine the Great, as commander in the West. Julianís first task would be to sort out the situation in Gaul.

Germans from the Authorís collection

Julian was a scholar with a bent for war, which was quite fortunate as at that time Gaul was overrun with bands of roving Germanic barbarians (the Alamanni) held at bay only by the strong walls of various fortified towns and cities.

Leaving Vienna with a comparatively small force, Julian fought his way through Gaul until he had pacified all the Roman territory south of the Rhine. His tactics were to fight only when he was sure of winning, avoiding the larger groups of Germans until his steadily-growing army was large enough to deal with them.

With Gaul now safe, Constantius decided that now was the time to deter the Alamanni from future raids by launching a two-pronged punitive strike into German territory itself. His newly appointed magister peditum, Barbatio, would attack with 25,000 troops from Southern Gaul, and Julian would attack from Northern Gaul with his 13,000 troops.

Julianís first thrust was very successful: the barbarians were caught napping on a series of islands in the centre of the Rhine and largely slaughtered, with the Romans able to re-stock from the Alamanniís own supply train and fields.

Barbatio, however, was not doing so well. Surprised with the speed of a German advance against him, he was forced to retreat back to his winter quarters: leaving Julian isolated north of the Rhine.

Julianís small force proved too much of a temptation for the Alamanni commanders to resist. Chnodomar, one of their Kings, led a force of some 35,000 tribesmen against him where he was camped near Argentoratum, modern day Strasbourg.

Confident of victory, the Germans first sent envoys to Julian, demanding he retreat from their territory. Julian held on to the envoys until he had finished the construction of a fortified camp, then released them and advanced to do battle.

The Roman army set out at dawn, and marched some 21 miles forward on a hot August morning to where the Alamanni were arrayed. Julian wanted to wait until his men had had a chance to rest, but his generalís were keen to do battle. Persuaded to fight, Julian began advancing his men down from a hill towards the German lines.

The Battle

The Battle

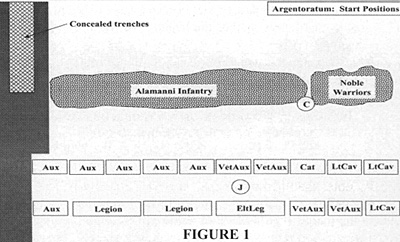

The Germans were deployed in a line with their right flank anchored on some difficult terrain: either a wood or an area of marshy ground. Within this, they had constructed some sort of ambush, with some translations even stating that they had men hidden in trenches.

Whatever form this trap took, Julian didnít fall for it. His battle-line stopped well clear of whatever it was and deployed for action.

Julianís left wing comprised a line of auxiliary infantry backed by legionaries. His right was fronted by the clibanarii extra-heavy horse, backed up by his veteran auxiliaries and his elite Palatine troops, with its open end protected by light horse. A more exact deployment is given below and in Map 1.

The Germans were massed in a long line with, according to the commentaries, their noble cavalry deployed on foot to bolster the morale of the great mass of tribal levy.

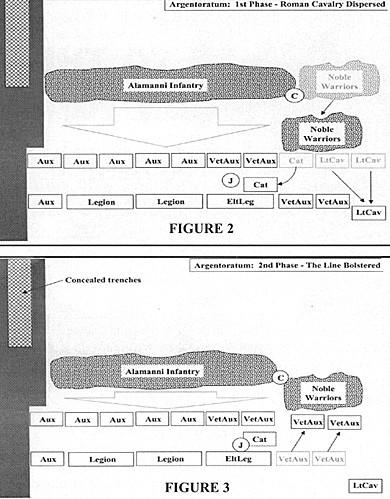

As the battle began, the Germans launched a fierce charge at the centre of the Roman line. In almost the first clash, the Roman clibanarii commander was killed, with the Roman cavalry falling back in panic and disorder as a result.

As the battle began, the Germans launched a fierce charge at the centre of the Roman line. In almost the first clash, the Roman clibanarii commander was killed, with the Roman cavalry falling back in panic and disorder as a result.

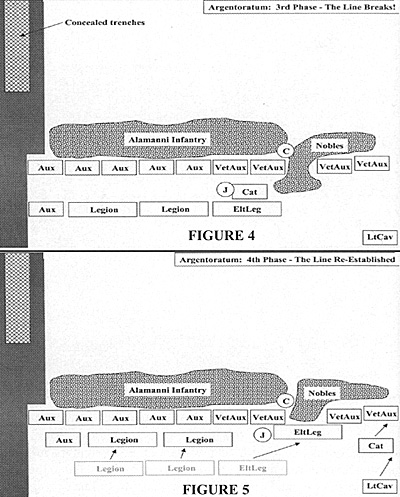

The Roman veteran auxilia, the Batavii and Regii, charged into the gap caused by the cavalryís retreat, holding the Roman line. The retreating clibanarii were prevented from leaving the field by the Palatine legion, then rallied by Julian himself and hurled back into the fray.

Meanwhile the Roman left was slowly pushing forward, but such was the pressure on the Roman line that a group of German nobles burst through the centre. Quickly the Palatine legion, now clear of panicked cavalry, charged the triumphant Alamanni and re-established the Roman battle-line.

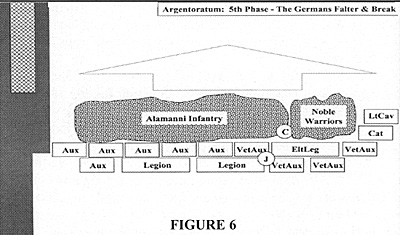

Now the superlative Roman mincing machine came into action. Grinding forward, the Romans slowly but surely drove the Germans back. The enemy line bowed then broke, with slaughter ensuing as the Romans took full advantage of their victory.

As the battle began, the Germans launched Chnodomar was captured and lost over 6,000 men. Only some 250 Romans have lost their lives. It is the high point of Julianís military career.

As the battle began, the Germans launched Chnodomar was captured and lost over 6,000 men. Only some 250 Romans have lost their lives. It is the high point of Julianís military career.

Numbers Present

Julians force was around 13,000 strong. Exact numbers and designations are difficult to deduce, but the list below is probably about right:

- 1,500 elite legionaries (possibly the Primani legion, or elite guard units such as the Scutarii, Armaturae and Gentiles)

- 2,500 veteran auxilia (four cohorts: the Cornuti, Bracchiatii, Batavi and Regii)

- 3,000 average legionaries (possibly the Joviani, Heculani, and Celtae legions, and perhaps also the Primani if the elites were the guard units mentioned above)

- 3,000 other auxilia (six cohorts including the Petulantes, Heruli and Sagitarii light bowmen)

- 600 cataphract cavalry

- 2,500 or so light cavalry, some of which were horse archers

Chnodomar could field a force of some 32,000 foot, the majority of which would have been poor quality tribal levy. There would also have been noble cavalry (around 2-3,000) either dismounted or with light infantry skirmishers mixed in.

Wargaming Argentoratum Using Vis Bellica

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 90

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com