When Lord Cornwallis retreated to Wilmington, North Carolina after his pyrrhic victory at Guilford Court House, he left behind young Francis Lord Rawdon to control South Carolina. Rawdon confronted skilled guerrilla leaders including Thomas Sumter, Andrew Pickens, and Francis Marion. These men led their partisan bands against the scattered British garrisons and their tenuous lines of communication. Cornwallis calculated that Rawdon could hold his own against the partisans. He anticipated that the rebel field army would continue to oppose his own army.

Then came the alarming news that Nathanael Greene, contrary to Cornwallis’s hopes, was marching on the British base at Camden. Rather then wait for the rebels to concentrate overwhelming force against him, Rawdon resolved to attack Greene before all of his supports arrived. He armed everyone in his command including teamsters and drummer boys, and on the morning of April 25, 1781 departed Camden.

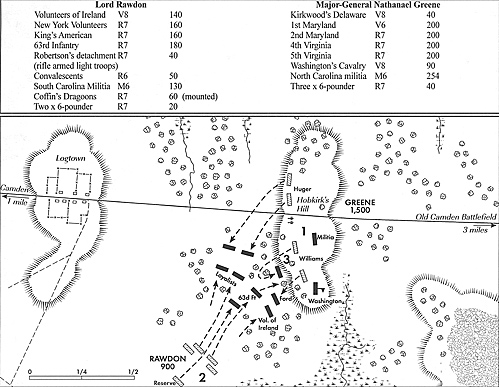

Two miles away stood Greene’s army atop Hobkirk Hill. The terrain was the typical pine woods of the region. The American west (right) flank rested on the Wateree River, the east flank on a swampy bottomland known as Pine Tree Creek. The long axis of Hobkirk’s Hill ran east and west. Toward the south, the direction of the British approach, the ground sloped about 100 yards to a bushy plain. The road from Camden to Waxhaws, the Great Road, bisected Greene’s position. The map, taken from Craig L. Symonds “A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution”, depicts the terrain and the historical positions.

Making skillful use of the wooded, swampy terrain, Rawdon managed to lead his 840 infantry, 60 cavalry, and two six-pounder guns right up to the American picket line before being discovered. Captain Robert Kirkwood and his devoted Delaware continentals managed to delay the British long enough for Greene to deploy his army. On the right of the Waxhaws road stood the 4th and 5th Virginia Continentals. On the left were the veteran 1st and 2nd Maryland. Some 254 North Carolina militia provided a reserve while Lieutenant Colonel William Washington’s 87-man cavalry detachment (only 56 with horses) served as a veteran, mobile strike force. Although Rawdon had excellent intelligence regarding the composition of Greene’s army, he did not know that forty artillerists and three six-pounders had completed a forced march to reinforce the Americans. Greene stationed these guns on the road and concealed them behind his infantry. Greene’s entire force numbered about 1,250 men.

Rawdon flung his forces forward into a characteristically impetuous frontal charge. The two outposts managed to buy enough time for the rebels to prepare to fight. When the American artillery unmasked, their rapid discharges of canister disorganized the British advance. Seeing that his own line overlapped the British line, Greene ordered both wings of his army to turn the British flanks, sent Washington’s cavalry on a deep envelopment, and committed the 1st Maryland and 5th Virginia in a bayonet charge to fix the British center. This maneuver should have led to an American victory. The 1st Maryland was one of the finest regiments serving in North America. It had broken Tarleton’s infantry with a bayonet charge at Cowpens and driven back Cornwallis’s Guards at Guilford Court House. Inexplicably, at Hobkirk’s Hill its morale collapsed and in broke and ran. The British 63rd Regiment capitalized on the ensuing disorder in the American ranks and pressed forward. It defeated the 2nd Maryland and turned to strike the Virginians in flank. The 4th Virginia became unnerved and broke leaving Greene with only one reliable regiment and his guns to hold his position. Greene ordered his army to retire. While helping manhandle his guns from the field Greene himself narrowly avoided capture. Fortunately, Washington’s cavalry returned and skillfully covered the American retreat.

Considering the forces involved, losses were astonishingly high. Greene lost 132 killed and 136 wounded or prisoners while Rawdon lost some 260 casualties. The high proportion of rebel killed to wounded indicate that the bitter enmity between the two American armies — three-quarters of Rawdon’s army composed loyalist units — resulted in the massacre of wounded and surrendering rebels.

For the wargamer, Hobkirk’s Hill offers an elegant exercise in Revolutionary War tactics. To reflect Rawdon’s undetected approach march have the American player set out all of his infantry and cavalry. Greene can also place two 50-man outposts (detached from any units he chooses) in front of his mainline at a distance of one rifle shot away from the mainbody. These outposts should not be revealed until after the British setup. Then allow the British player to set out his forces no closer than twice rifle range distance. To reflect the surprise presence of the American artillery, allow Greene to conceal his artillery’s position until they either fire, move, or a British unit enters within musket range of the artillery position. In this latter case, if an intervening American unit screens the artillery from the British line of sight, continue to keep the artillery off the table. On the first turn, Washington’s dragoons cannot move. Instead of performing picket duty, they were eating breakfast, horses unsaddled, when the first shots rang out!

The order of battle provides a full range of infantry types for both sides, ranging from the veteran 1st Maryland and the loyalists of the Volunteers of Ireland, a crack Tory unit, to the humble North Carolina militia which served with Greene and the inexperienced South Carolina Provincial regiment which served with Rawdon. The following list rates the troops according to our Generalship rules. Militia (M) rating means a unit can endure only one critical threat before it must test morale, a regular (R) can endure two, and a veteran (V) three. The morale is associated with a numerical rating that is the point on a D10 that a unit must meet or roll under in order to pass morale.

For example, when the South Carolina Militia confronts a rebel unit to its front (one threat) it must test and roll a 1-6 on a D10 in order to pass morale. These morale ratings can be translated to whatever preferred system you use. The second number is the unit’s numerical strength. Note that the strength for the British convalescents is totally speculative. If using Generalship Rules*, give both Rawdon and Greene three leadership points and give one to William Washington who can only apply it to his own mounted force.

The goal is to drive the enemy from the field while inflicting more losses than receiving

There were significant detachments from both armies operating in the region. Both commanders expected these forces to rejoin them soon. On the rebel side they included units Greene sent to operated with Marion; namely the men of Lee’s Legion (300 horse and foot), Captain Oldham’s company of Maryland Continentals, and one field piece. Irregular forces included Marion’s men and Thomas Sumter’s South Carolinians. Since the ‘Gamecock’ was erratic and stubborn when it came to cooperating with anyone, a die roll could determine the size of the force he contributes. On the British side, Rawdon had detached Colonel John Watson with about 500 men to hunt down Marion. Add all of these forces, generate some appropriate ‘southern’ terrain, and have a bash to determine who controls the Carolinas.

Lord Rawdon

Major-General Nathanael Greene

A recent research trip to South Carolina rekindled my interest in the southern campaigns of the American Revolution. After I returned, and recovered from “Low Country Cooking” (note to my southern cousins: the age of refrigerators and freezers has arrived, it is no longer necessary to pour salt into everything to preserve the food) I remembered what good fun a friend and I had when we refought the April 25, 1781 Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill. Like many southern engagements, this battle featured small forces on both sides. Thus, it lends itself to a fine tactical refight easily completed in just a few hours.

A recent research trip to South Carolina rekindled my interest in the southern campaigns of the American Revolution. After I returned, and recovered from “Low Country Cooking” (note to my southern cousins: the age of refrigerators and freezers has arrived, it is no longer necessary to pour salt into everything to preserve the food) I remembered what good fun a friend and I had when we refought the April 25, 1781 Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill. Like many southern engagements, this battle featured small forces on both sides. Thus, it lends itself to a fine tactical refight easily completed in just a few hours.

The History

How to Refight the Battle

A What-if? Scenario

Order of Battle

Volunteers of Ireland V8 140

New York Volunteers R7 160

King’s American R7 160

63rd Infantry R7 180

Robertson’s detachment R7 40 (rifle armed light troops)

Convalescents R6 50

South Carolina Militia M6 130

Coffin’s Dragoons R7 60 (mounted)

Two x 6-pounder R7 20Kirkwood’s Delaware V8 40

1st Maryland V6 200

2nd Maryland R7 200

4th Virginia R7 200

5th Virginia R7 200

Washington’s Cavalry V8 90

North Carolina militia M6 254

Three x 6-pounder R7 40Map

Editor's Note: These are the author’s rules and are available from him at Jim Arnold, Burro Station, Big Little Dry Hollow, Lexington VA 24450-6936.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 88

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com