Terrain

Well, it can be either open rough or very rough! Oh, to be sure, we can differentiate between woods and swamp, mountains and desert, but the real key is how inhibiting is the terrain of the movement of our units, (or some of the units). Obviously this can be a sliding scale, open being the least, rough - some inhibition, and very rough- very inhibited movement. To note these in a shorthand we will use the letters C, R, and V. Other considerations of terrain either go hand in hand (for the impediment to movement of a formed body of men will in some sense also determine its ability to protect them in combat or offer them a comparative advantage) and generally this is directly proportional.

Forces

Well here again we really have only three qualities. Both sides can be equal or relatively equal to the other, which is the usual case.However there can be cases where one side can be somewhat superior to the other, and others where he can be VERY superior to the other. Here again this “superiority” is of course a vague and general term, but that in no way invalidates either its existence or its meaning. We might call a scenario “unbalanced” in the last case and we might expect to see some compensating benefit if we wanted to restore it to equality.

That is, if we did.

Nevertheless we can express this symbolically just as our terrain with the symbols for equality or rough equality, “<” for greater than and a “< <” for significantly greater than.

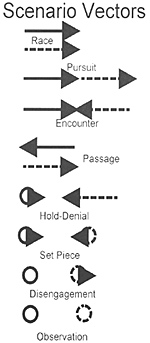

Now the real key to all this is the “Vector” of the game or the direction of movement of the game. That is, the patterns in which the two armies are designed to maneuver on the table top. Each game will have a vector for each army. These are shown in the graphic called SCENARIO VECTORS. The one army has the solid vector and the other the dashed vector. Each represents a direction of movement that each army is expected to follow, which are induced by the victory conditions or the injunction of the umpire. There are really only two vectors for each army, a moving vector (the line, solid or dashed, plus the arrow) which represents a “marching on the field from off of it” and the “immobile vector” or the small circle which means that that side sets up on the field. Shown with each “pair” of notations are the type of game that will be engendered. For example the top one shows both armies moving from the same side in the same path. Obviously this is a “race” situation. One can envision them both starting out on one side of the table on the long edge and moving across the board to be the first to get to a strategic bridge. The second is a pursuit where one side is in column and the other is following it. The starting positions are different, but the direction of movement is the same. The pursued forces are seeking a bridge, fort, position, or goal which assure them safety, while the others are attempting to bring them to bay or head them off before they reach it.

That all of them are playable is another matter. Well to be sure, ALL are playable, enjoyable perhaps is the real problem.

Let me give you an example. We can construct a scenario by choosing “one from column A, one from column B, and one from column C” as it were. So let’s assume we chose clear terrain, roughly equal forces and the set piece vector. God knows we all have played in enough of these. On the other hand we might chose say very unequal forces, very rough terrain, and the vector Passage. Well, we have now the classic infiltration scenario. If we were to chose Rough terrain, one side greater, and the Vector “Hold/Denial” wee would have another very familiar scenario type.

OK Otto! So What!

Simple. What if we had a battle where one side was very much greater than the other in forces, on clear terrain, with a set-piece vector. Not very fair as the inferior force has no compensating terrain, or a vector (like infiltration or disengagement.) that will allow them to operate normally. Or regardless of forces, or terrain, the vector “Observation” simply assumes that both sides wish to stay in place and observe the enemy. Another interesting game, though perhaps out of the ordinary. How does one sit and do nothing? What are the victory conditions? All of this is important because most of our games tend to be within the style of equality. Either, an equality of forces, or an inequality of forces but with a compensating benefit in terrain or vector. Yet that is not real war. Real war is very much made up of unequal situations and odd occurances as both sides may have different attributes and plans, and their generals motivated by different imperatives.

So then what, one might add, is the benefit of all the symbols. Well, quite simple, really. They form easy mental and pictorial tags to quickly aid you in scenario design. Such that you can have things like:

Which is basically design an encounter battle or...

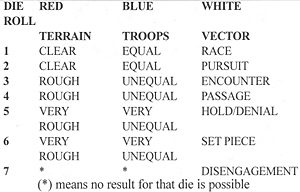

Which is a pursuit battle. A side benefit of course is the ability to do this randomly with, say two six sided (red and blue) and one eight sided die, (white). See Chart on next page.

Given this then you could make up scenarios almost on the fly, obeying the dictates of the random die rolls. Obviously you could modify the chart in many ways. For example, you might make all of the die 8 sided, and for the terrain die allow for a 7 one player to chose or for the 8, the other player to chose. Likewise for the forces one could put in for 7 “start out unequal but have reinforcements later” and for 8 “start out very unequal but gradual reinforcements:” It really is up to you once you realize that there are only these simple “dimensions” to a scenario.

One could also extend this further to a mini-campaign with absolutely no need for dice, maps moves, overlays, or record keeping, provided one was willing to accept the dictates of chaos or chance. For example you could say that two countries, (forces?) (armies?) are in a campaign. It will be from 1 to “N” games (N being any number you want, predetermine, die for, or test for. I will explain that later. Each “move” or turn of the campaign, is a “battle” or “scenario” as designed above by a die roll. Thus assume you have eight encounters planned. Each one you dice for and you get a series of 8 completely unpredictable scenarios that are generated in their form, and which you arrange in the specifics. At the end of each a winner and loser is determined. When the campaign is fought the person with the high score wins. You can, of course, make this as complicated as you want, but that would destroy the elegant simplicity.

This may seem rather bizarre, having things like a Reconnaissance in force being as decisive as a major set piece, but it is not historically inaccurate. Succeeding in such a thing may prevent a disastrous riposte by the one side which will have serious effects on the campaign on areas and forces not seen on the battlefield but which are decisive in their own. It is up to the umpire to then stitch it all together in a story. If you are willing to accept the dictates of fate in this matter, then you can have an exciting and enjoyable game and have a lot of fun, and not be condemned to fighting endless set-pieces or mini-Verdun’s with troops stretched from edge to edge.

What I meant on “testing” for the end was that after each battle you roll a die, and say, if it is an 8 on an 8 sided die, then the campaign ends and the score is totalled. Thus you do not even know which battle will be the last.

At the same time, you could add a few more die rolls, or change the die face number and add or adjust the results for the new faces. On the whole though you are going to find it hard to puzzle out any more scenario vectors than what we have, and thus the dice will have to be on base 8, or, conversely, you could decide you want more set pieces and encounters, and use a 12 sided die and and have, say more faces yielding those results.

In fact you could have a whole range of charts and randomly dice on which chart to use, that is which chart of random results to use.

In all cases you are presented with a situation that simulates EXACTLY what real generals face in a campaign, that is, where they are frequently called into action through the plans of the enemy, in unforeseen events, or in situations they would rather not be in.

In effect then, all of this has been an illustration of what might be termed “The Chaos of Events” or another in our articles of the effect of Chaos in War.

It’s shocking, really, how simple this is! When you sit down and consider it there are really only three elements of scenario design. These are 1) The terrain, 2) The forces, and 3) the vectors. Each of these can be represented by an abstract quality and from there the type of scenario, and what will happen is pretty much set. Let’s consider these three “attributes” of a scenario.

It’s shocking, really, how simple this is! When you sit down and consider it there are really only three elements of scenario design. These are 1) The terrain, 2) The forces, and 3) the vectors. Each of these can be represented by an abstract quality and from there the type of scenario, and what will happen is pretty much set. Let’s consider these three “attributes” of a scenario.

Now, understanding that the notations and vectors are arbitrary and can apply to either side, one can see that among these one has pretty well exhausted the possible types of scenarios, though one may never exhaust the possible settings, variations, and enactment of it. Thus an encounter engagement in the ancient world does not materially differ (in its nature and thrust) from an encounter engagement in the Musket period or the modern world. One could of course multiply these basics by doubling for each side (two pursuits, one where the “lined” is the pursuer and one where the “dashed” is) but that would merely multiply the case without purpose. A pursuit is a pursuit regardless of who is doing the pursuing or being pursued. Working on this then by multiplying the types of terrain, the force ratio, and the vectors we find that there are 72 different TYPES of scenario POSSIBLE!

Now, understanding that the notations and vectors are arbitrary and can apply to either side, one can see that among these one has pretty well exhausted the possible types of scenarios, though one may never exhaust the possible settings, variations, and enactment of it. Thus an encounter engagement in the ancient world does not materially differ (in its nature and thrust) from an encounter engagement in the Musket period or the modern world. One could of course multiply these basics by doubling for each side (two pursuits, one where the “lined” is the pursuer and one where the “dashed” is) but that would merely multiply the case without purpose. A pursuit is a pursuit regardless of who is doing the pursuing or being pursued. Working on this then by multiplying the types of terrain, the force ratio, and the vectors we find that there are 72 different TYPES of scenario POSSIBLE!

(R) () ()

(C) (< <) ()

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 88

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com