Melas' attempt at defeating the Armee de Reserve while it was astride the river Po was foiled by Lannes defeating a much larger Austrian force at Montebello on June 9th. Melas made the fatal decision to concentrate in the vicinity of Alessandria in hopes to gather a force large enough to fight his way through to Lombardy. This course of action lead to the collision of the two armies at Marengo June 14th 1800.

By the 12th of June Bonaparte had collected a force of 32,000 men and 41 guns at the Scrivia river near Tortona, and Melas had managed to collect nearly 31,000 men in Alessandria. Bonaparte had not anticipated Mela's aggressive moves and indeed was sure he would attempt to escape and as a reaction divided his forces to close all routes to the Austrians.

Gardanne's augmented division, (5,300 infantry, 685 cavalry, and 2 guns,) drove the Austrian covering force back towards Alessandria during the afternoon of the 13th of June. By 6pm Gardanne's division had pushed the Austrians back to the town of Marengo. Gardanne attacked the town in strength. General O'Reilly, commanding the Austrians, decided that it was untenable to defend Marengo with the Fontanove stream to his rear, so he withdrew beyond the Bromida. Gardanne's men advanced through the town of Marengo and only halted when they were brought under fire from the 14 guns in the tete-de-pont on the east bank of the Bromida. Gardanne reported that he had driven the Austrians over the Bromida, and gave the impression that the bridge across the river had been secured. As Marmont arrived, he realized that the bridge and the tete-de-pont were intact. He brought forward eight guns in attempt to silence the Austrian guns. His attack was unsuccessful. He then suggested that Gardanne launch an infantry attack against the Austrians. Gardanne refused, and Marmont turned back to ride the 11 kilometers to Bonaparte's headquarters. He was overtaken by a heavy downpour which made the roads treacherous and forced him to spend the night in a wayside farm. He did thus not report to Bonaparte until the following morning, June 14th.

With no report of the battle from either Gardanne or Marmont, Bonaparte ordered Desaix with Boudet's division to march south-west through Rivalta to cut the road between Allessandria and Genoa and Lapoype to march towards Valmenza. Bonaparte then retired for the night with his army widely dispersed and safe in the firm belief that Melas would not attack.

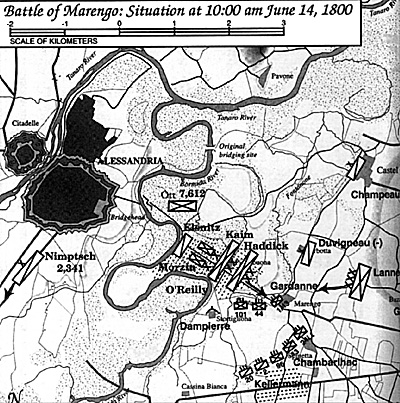

Gardanne's division was deployed in front of Marengo with Chambarlhac's division in close support. These divisions had two cavalry regiments and 6 or 8 guns in support, commanded by Victor. General Lannes with Watrin's division and 12 guns were bivouacked about 7 kilometers away, southeast of Marengo. Behind them was the main body of the cavalry and Monnier's division with two guns. Close to Bonaparte's headquarters the Consular Guard was bivouacked.

Meanwhile, Melas had given the orders to attack east at dawn on the 14th of June. His main column would attack straight down the road through Marengo and San Giuliano making for Piacaenza. The right of the column would be covered by O'Reilly's command and the left column under Ott, who was to move on Sale by way of Castel Ceriola. The stage for the battle of Marengo was now set.

The Austrian attack faced numerous obstacles. It had to pass over the Bromida and debauch from the tete-de-pont which only had one exit.

O'Reilly, whose detachment had spent the night within the tete-de-pont, advanced and pushed back the French outposts. Which allowed General Hadik's division to deploy from the tete-de-pont

The opening of the Austrian attack was heralded by their artillery, which was heard at Bonaparte's head quarters, Toro de Garofoli 12.5 kilometers to the east. At the same time Bonaparte had confirmed the order to send Lapoypes divisions marching on Valenza. He was so convinced that Melas would not attack that he disregarded Victor's message, which he received about 9.30 am informing him that the Austrians were indeed forming up for a major attack. Bonaparte was still convinced that Gardannes report, which said he had thrown the enemy back over the Bromida, was true. It was not until Marmont reported to him in person that Gardannes report was false, that he finally understood the danger he was in. He had dispersed his force and was being attacked. He immediately ordered Wattrin and Monniers to advance with their divisions towards Marengo and issued the same orders to the cavalry and the Consular Guard. He then dispatched ADC's to recall Desaix and Lapoype.

At this point the French seem to have been able to muster 22,000 men against the Austrian's 31,000. These numbers are very deceiving. The Austrians were attacking on a very narrow front, over a stream and through or around the town of Marengo into the plain behind Marengo. Given these disadvantages the battle at this stage was very even.

The Austrian attack was in four lines, the first consisted of Haddick's division, followed by Kaim's division, and Elsnitz's cavalry behind them. The last line was composed of Morzin's grenadiers. Ott's command was to advance to Castel Ceriolo and then on to Sale. On the right O'Reilly was to advance to the right of the attack, find a crossing over the Fontana, and then fall on the French flank.

Around 9am Melas received reports of enemy to his rear. He reacted by detaching Nimsch's cavalry brigade to march towards the reported position of the enemy. This turned out to be a false report, and the six squadrons would be sorely missed later in the day.

Hadik seems to have launched his attack before his entire command had formed for battle. Six battalions made up this attack and were halted at the Fontanove ditch, which was deep, marshy, and edged by dense thickets. As they attempted to cross, units of Gardanne's division poured fire into them. Hadik, seeing that the attack was faltering, was ordering a withdrawal when he was mortally wounded. Kaim moved his troops through Hadik's but his attack was also repulsed. The Austrians, realizing the nature of the obstacle that the Fontanova stream presented, issued orders for the pioneers to place footbridges over the stream, unfortunately the pioneers were at the rear of the column with the Grenadiers. Melas, while waiting for the footbridges, issued orders for the emperor's dragoons to find a crossing and attack Gardannes division in the flank. Some of the regiment managed to cross, but as they were forming they were charged by French cavalry led by Kellerman. The survivors routed back across the steep banks of the Fontanove. On the Austrian right O'Reilly's men had been held up by French troops in the farmhouse of Stortigliano. This farm was held by men of the French 44th and 101st demi-brigades.

When Ott could finally extract his column from the confusion around the bridge head, he crossed the Fontanove without opposition and advanced on Castel Ceriolo. Instead of following his orders he marched to the sound of the guns, and swung in towards the center. His troops engaged Wattrin's, which were advancing towards Castel Ceriolo. Otts' forces threw the French troops back. Bonaparte's reaction was to send the Consular Guard to support Wattrin. The Guard, comprising 800 men, deployed on Wattrin's right in columns, preceded by skirmishers. The Lobkowitz Dragoons charged the Guard, who unlimbered their guns, and firing canister forced the Dragoons to retire. As the Dragoons retired they were in turn charged by French Hussars. The Hussars broke the Dragoons and charged two battalions of the Spleny infantry regiment. Spleny's two battalions were supported by a battalion from the infantry Regiment Frohlich. Unable to sustain the charge, the Hussars broke. The Austrian infantry then advanced to close range of the Guard and a firefight ensued. Neither side gained an advantage until the Guard was charged in the rear by Austrian Hussars, who captured a number of guns. Which precipitated Lannes withdrawal.

At the same time, to the south, the town of Marengo fell to the Austrians. The town had been defended by a battalion of the 43rd demi-brigade, and two other battalions to the rear in support. The pioneers had managed to place foot bridges over the Fontanove, allowing men from the Archduke Joseph's regiment to gain a toehold in the town. At the same time five Austrian grenadier battalions advanced over the bridges and threw Victor's men back. The French under Victor and Lannes were now being surrounded. Ott was advancing upon their right flank, and O'Reilly had managed to bypass the farm to their left. As the French began to retire they gave up Marengo, but the orderly withdrawal quickly turned into a rout. Kelerman's cavalry remained to stem the tide of Austrians and saved the French from total destruction.

Battle Won?

Melas felt that the battle had been won. Melas, who at 62 had been in the saddle for most of the day and had suffered a minor wound, retired to Allesandria, leaving the mopping up to Zach, his chief of staff.

Around mid-afternoon as the remains of the French troops neared the hamlet of St Giuliano Vecchio, Desaix rode up, followed shortly by units of his Division. At this point Desaix and Kelermann seemed to take over the arrangements for a counter attack. As the remains of Victor's men began to rally, Marmont placed the five remaining guns that had just been brought up and the eight guns of Boudet to the right of the road to San Giuliano. The position of the guns as well as of the rallying troops was not visible to the Austrians due to the hill just west of San Giuliano. Boudet deployed his troops for battle, as did Desaix. Just as they finished deploying, Bonaparte ordered the line to advance. As the French advanced towards the Austrian's a stray shot from the French lines killed Desaix. The 9th Legere were attacked in the flank by Austrian cavalry, and Guenard's brigade was stopped by three battalions of the infantry Regiment Wallis.

In a heartbeat the whole battle would change. Kellerman led his cavalry in a charge which struck the flank of the Wallis infantry Regiment. He also engaged two battalions of Austrian Grenadiers deployed in column in the flank. The whole Austrian Center collapsed, and the Austrians did not stop running until they were back in Allesandra. The next day Melas signed a convention to evacuate all of Western Italy and withdraw his army behind the Mincio.

Although this battle and its events where rewritten many times by Bonaparte in later years, it was a victory of his generals, most notably Kelermann and Desaix. The battle is often portrayed as a desperate fight by the outnumbered French, but if one looks at the terrain and the numbers of Austrians that could be deployed at any one time, one realizes that the battle was much more balanced than we are led to believe. In fact it was a brilliant fight by the Austrians who fought out of a bridge head, over a stream that was difficult to cross, through a major choke point with a town in its center and into the plains beyond. At the same time they routed the defending French. Desaix's advance and the charge by Kelerman were brilliant counterattacks and saved a battle already lost.

More Marengo

The prelude to the battle of Marengo was in Bonaparte's advance over the Alps. As his army debauched into the fertile plains of Northern Italy, Bonaparte made the decision not to advance his army to relieve the siege of Genoa, where Massena was desperately holding, but rather to march on Milan. On June 2nd, the day Massena surrendered in Genoa, Bonaparte entered Milan, and Melas the overall Austrian commander in Italy, finally became aware of the danger to his lines of communications.

The prelude to the battle of Marengo was in Bonaparte's advance over the Alps. As his army debauched into the fertile plains of Northern Italy, Bonaparte made the decision not to advance his army to relieve the siege of Genoa, where Massena was desperately holding, but rather to march on Milan. On June 2nd, the day Massena surrendered in Genoa, Bonaparte entered Milan, and Melas the overall Austrian commander in Italy, finally became aware of the danger to his lines of communications.

14th JUNE

Historical Narrative

Marengo Order of Battle

Wargame Comparison Introduction

Age of Bonaparte

From Valmy to Waterloo

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #79

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com