From Polotsk to Vitebsk

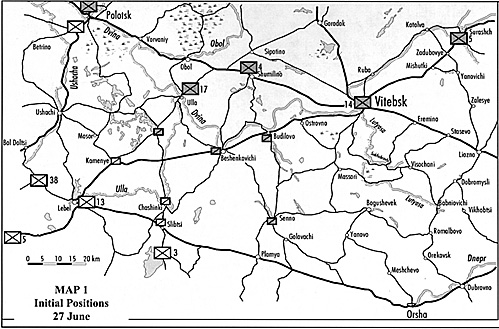

The most recent Napoleonic campaign fought by the Old Colony Wargamers was posed as part of the 1812 invasion of Russia. The immediate inspiration for this was that I had gotten my hands on a Soviet topographic map of the Vitebsk Oblast at a scale of 200,000:1. This covered a large enough area in sufficient detail for our purposes, we had plenty of lead, and the members of the club were ready for another campaign. See Map 1.

A Russian corps and a French corps are facing one another at Polotsk, not commanded by players in the campaign. The French are centered on Lebel, the Russians, part of Barclay's army, are spread from Vitebsk to Ulla. To the south, not commanded by players, are Napoleon and the rest of the French army pursuing Bagration, who is falling back on Orsha. Near Gorodok, also out of player command, is Barclay.

The French are to locate an enemy force known to be between Orsha and Gorodok, evaluate its strength and intentions, then either cut the corps in Polotsk off from the remainder of the Russian army or isolate Vitebsk from Orsha, separating Barclay and Bagration. They have three French and one Wuttemburg divisions in an infantry corps, with three brigades of attached light cavalry. In addition, there is a heavy cavalry corps south of Plamya, which Napoleon may release to the French commander if the situation warrants.

The Russians must maintain communications with Polotsk, covering the withdrawal of the corps there if necessary; be prepared to move South to join Bagration near Orsha; and counterattack the flanks of any French move on Vitebsk or Orsha. The Russian commander has four infantry divisions in two corps, each with attached light cavalry. He will be reinforced by a grenadier division, but does not know this at the outset.

There are major supply depots at Lebel (French), Gorodok, Vitebsk, and Orsha (Russian), all of which are garrisoned. There are also some LOC troops not controlled by the players. The Russians have to cover a wide front with too few troops, and are expected to counterattack if possible. The French have to attack without an overall superiority in numbers or quality. The senior commanders on each side were given a description of the situation as it is known to them, their orders, and their order of battle, along with an introduction to the scenario, terrain notes, and a few pages of campaign rules. Division commanders were given similar material, but no orders. The senior commanders then issued written orders to their corps and divisions, and the orders set out by courier.

Communications

Messages are carried by couriers which travel at 8 km/hr. For any substantial order, I imposed a 30 minute delay between receiving information and the response. If the message travels by a route which is held by the enemy, there will be problems. I usually use a 25% chance that the messenger (with message) is captured, 25% that he simply fails to deliver the message, and 50% that there is a delay that depends on how much of a detour will be necessary. If the message is wrongly or confusingly addressed, or doesn't specify a location for the recipient, I also impose a delay.

I use a database to keep track of all the messages. This uses the distance to be traveled and any delay to calculate the arrival time. The messages can then be sorted by recipient and arrival time, so I can pass them on at the right time.

Division commanders get reports from the referee on their progress and any intelligence they may receive. It is up to the commanders to pass on any information that they think relevant. One of the salient characteristics of a good campaign player is simply remembering to report what is going on, and remembering to address, date, and sign his correspondence.

E-mail is both a godsend and a curse. One of the biggest problems in keeping a campaign underway is turning over the orders and messages. If you're doing it by mail, you can figure at least a week to send out information and receive a reply. If you do it by telephone, you will discover that the players think that they have told you something other than what you write down, and that of course they wouldn't have forgotten to assign cavalry to cover that road. Having written orders makes the whole thing run more smoothly and gives you a record to check back with. E-mail lets you do this much more quickly.

Of course, you will be sure to have someone who doesn't have access to it, which causes problems. The other problem is more serious: your players have to be extremely disciplined. All messages have to come through the referee, so that the appropriate time delays can be incorporated. Otherwise you get responses to information that hasn't yet arrived, and worse yet, these orders with the wrong times being used to generate another cycle of reaction. It is difficult enough keeping the campaign clock synchronized without players generating their own time distortion fields.

And They're Off

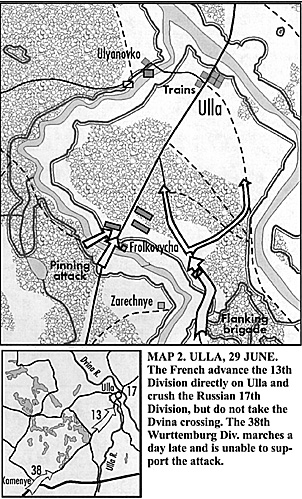

Ulla, 29 June: The French advance the 13th Division directloy on Ulla to crush the Russian 17th Division, but do not take the Dvina crossing. The 38th Wurtemburg Division marches a day late and is unable to support the attack.

Ulla, 29 June: The French advance the 13th Division directloy on Ulla to crush the Russian 17th Division, but do not take the Dvina crossing. The 38th Wurtemburg Division marches a day late and is unable to support the attack.

The French began by advancing the 13th Division directly on Ulla. It was supposed to be supported by the 38th Wurttemburg Division, but that division's commander ordered his troops to march the day after he was supposed to. Other French units moved on Kamenye and thence East towards Beshenkovichi, and up to Chashinki. Way down near Plamya the first of a long series of cavalry contacts began.

Units move an average of about 25 km a day, with the distance determined randomly each hour for each column (see CHART 1). The troops expect to rest for half an hour every two hours, and to march no more than eight hours a day. Exceeding these limits decreases unit strength until rested.

Our house tactical rules have a route column rate of .8 to 1 km/hr. If the units remain more than 500 m from the enemy, they get an extra move, and if on a road for the full turn these distances are doubled, giving a rate of 3.2-4 km/hour. This is close enough to the operational movement rate that we have had no trouble integrating the two. Units move across the map until they reach the battlefield, then move using the tactical rules. Rules where tactical move is very disparate from the operational move will cause problems, and you will need to adjust them.

Each battalion of infantry or regiment of cavalry strings out on the march to occupy 400 m of road, 600 m when moving cross-country. Columns are further extended by the addition of train units, one per artillery battery or four other units. Russians get another per division. This means that the lead units of a 20-unit division will be stopping for their first rest break before the tail units have left camp. A division needs a couple of hours to close up and deploy for battle. One of the advantages of having a couple of micro-campaign test games is that it will break players of the tendency to try to attack a deployed defense on the run from their march column before they spoil your big campaign by having their division chewed up to no purpose in the first encounter.

I take the commanders orders for their divisions, roll movement dice, and mark each hour's movement on the tactical-scale map. For each division I figure the length of the column and the time it will take to march that length. I can then tell each commander when the head of his column reaches a particular point and when his whole division is assembled.

Torn Between Two Rivers

Ulla was defended by a Russian division in position behind the Ulla River, but with the Dvina at his back. The French commander took a major risk, separating his forces and sending one brigade on a long march across a ford and up on the flank of the Russian position. [MAP 2] At this point the Russian division commander could see the two brigades attacking across the river and the head of the flanking column. He was convinced that he was being attacked by at least two infantry and one cavalry divisions, a misapprehension not clarified by the insufferable gloating of the French across the table, and began to withdraw over the Dvina.

I have a scouting algorithm that generates reports with an accurate report as an average and a variance that is a function of the reliability of the source. I find that in practice most sighting reports are highly limited by the spotting unit's field of view, which I determine by looking at the tactical maps. I use the algorithm only when a scouting unit has spent significant time in contact with an enemy that doesn't have an adequate screen, or when the populace is being questioned about what they've seen. At Ulla, the French brigades attacking across the river were on the table in complete view of the defenders. The flanking column was reported as a regiment of light cavalry screening an infantry column of unknown size (only the first battalion was in sight at first report). The Russian commander was left to draw his own conclusions.

Although the French attacking brigades took significant damage, the flanking column got good dice to move through the woods and cut off two Russian brigades which had been forced to attempt the very difficult maneuver of fighting a delaying action while withdrawing through woods without losing their cohesion. The Russians did succeed in getting all their trains, artillery and a jager brigade over the Dvina. This left them holding the bridge and covered their LOC through Shumilino, but this division was no longer an offensive threat.

Once is Never Enough

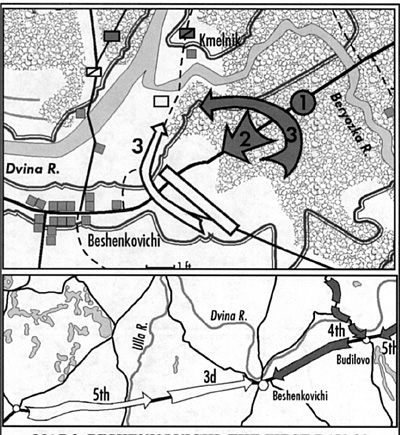

The delay inherent in communicating across distances of 80 km or more, as the Russians in particular had to do at the beginning of the campaign, is a major source of confusion for players accustomed to telephones. Cavalry contacts were made in the first hours of the campaign. By the time the information had traveled all the way back to headquarters in Vitebsk and new orders had travelled back to Ulla and Beshenkovichi, the situation had changed. An omission in the Russian cavalry screening dispositions left the road from Kamenye to Beshenkovichi uncovered, and French light cavalry took the town, scattering the HQ of a Russian cavalry brigade. The French 3d Division and the Russian 4th Division raced for Beshenkovichi, hoping to hold the crucial crossing point. The French arrived first and engaged the approaching Russians east of the town. [MAP 3] both sides were badly damaged in a long day of fighting, and it appeared that the next day would see another race between the French 5th and the Russian 5th Divisions to see who would be able to reinforce first.

Beshenkovichi, 29 June: 1. Russian 4th Division, moving from Shumilino via Budilovo is ambushed by elements of the French 3rd Division after crossing the Beryozka. 2. The Russian attack, attempting to gain the edge of the trees. 3. The Russians switch to an attack on their right, are forestalled by quicker moving French.

Beshenkovichi, 29 June: 1. Russian 4th Division, moving from Shumilino via Budilovo is ambushed by elements of the French 3rd Division after crossing the Beryozka. 2. The Russian attack, attempting to gain the edge of the trees. 3. The Russians switch to an attack on their right, are forestalled by quicker moving French.

The next morning the divisional commanders on both sides had orders to watch the enemy and wait for reinforcements, but a few desultory artillery rounds quickly led to a full-scale engagement. The French got the early advantage, and the Russian 4th Division had no remaining strength to hold position. The Russians had chosen to send their reinforcements on the north side of the Dvina and were still half a days' march away when the French 5th Division arrived and the remnants of the Russian 4th Division were forced to flee. The Russian 5th Division returned to Budilovo, where a general concentration was now in progress.

The French 13th Division had marched from Ulla to Beshenkovichi, followed by the Wurtemburgers (still a day behind), less a detachment left to watch the Russians at Ulla. The Russians had moved the 14th Division first south to Massori, then through Ostrovno to Budilovo. The shattered remnants of 4th Division had also fallen back to Budilovo, continuing on back to Ostrovno.

Losses, Recovery, and Reinforcement

Our tactical rules use a roster system to track unit strengths. A plain vanilla French or Russian infantry battalion or cavalry regiment would have an average strength of about 22 (maximum 32). Losses from fire, melee, and morale failure reduce this number, until at 0 the unit is no longer combat effective, and must withdraw.

In the campaign, half the losses suffered in combat are permanent. The other half can be recovered at 2 points a day if stationary and resting, 1 point a day if marching. If engaged in battle again, all losses become permanent. If a 0 strength unit is engaged in melee, it is destroyed and cannot be restored.

In addition, each side was provided with reinforcement drafts. These were in the form of a dozen or two strength points each week which could be distributed among units to restore permanent losses, with a maximum of four per unit. The French got only infantry points, while the Russians got a very few cavalry points. These arrived at the central depots at Vitebsk and Lebel. This is a highly abstracted system and probably overstates the availability of replacements. It seems to work, however, without adding a lot of complications.

I've already mentioned using a database to keep track of messages, which can otherwise become an overwhelming task. I also use a database to keep track of units, including their losses , recovery, and replacements. This can be done with little green notebooks, as Berthier ably demonstrated, but a little help is welcome. This database prints up the roster cards used to play the tactical battles. I collect the cards after the battles to count up the casualties and enter the results. The database gives me a quick way to print and hand out updated troop lists to the commanders, and even remembers which drawer each unit is supposed to live in. although it can't keep players from putting them away in the wrong place.

The Russians benefited especially from the replacement points because they were falling back on their LOC, so replacements caught up with them, while the French were constantly marching away from theirs. Similarly, battered Russian units fell back to a reserve position on the LOC where they could rest and regain strength more rapidly than French units which continued to march. After the second day at Beshenkovichi. The French chose to send the badly damaged 3d Division to Senno to recuperate and cover their right flank.

The French had requested the use of the II Cavalry Corps to follow up on their victories, and Napoleon now released one division with the second a day behind. This division, approaching Plamya, was the occasion of considerable confusion, with the Russian light cavalry having pushed the French lights west from the town, only to have these heavies appear behind them. The French heavies assumed the road to Lebel was in their possession and sent messages reporting their presence to Lebel, the last location they had for French HQ, only to have the messengers intercepted. The Russian cavalry withdrew, worked around Plamya, and ended up north of the town, observing the French.

The Russians had also received reinforcements, as the 1st Grenadier Division arrived at Vitebsk. The French now advanced on Budilovo, attempting and failing to catch the withdrawing Russians with a short pincer movement on the way.

More Napoleonic 1812 Campaigning

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #78

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com