This article, and many of the handouts with it, was originally given at a Seminar at the 1999 Historicon entitled Campaigns or Campaigns, a workshop on how to plan better to have more successful campaign efforts.

The four main issues that must be dealt with in any campaign can be summarized under the ruberic "SICC" - Scope, Interest, Control, and Capacity.

Interest: How many people besides you are interested in doing it, and will make the commitment in time, energy and money to see it through?

Control: How will you control the function and the run ning of the game?

Capacity: What material will be required to run the cam paign?

While we will deal with all of these issues later in the open forum section, In my remarks now I want to deal with one topic which is, I believe, of over-riding importance. That issue is SCOPE. Now I'm going to expand this a bit and call it SCOPE and FOCUS, for they are intimately related and both vital to the success of a campaign effort.

Scope is the first and most important thing to decide, for it is upon this point that most campaigns will founder. Scope is simply the campaign venue, the limitations of the campaign. E.g. is the campaign to be a narrowly focused episode dealing primarily or solely with military events, or will it be a more open-ended broad-based affair, which will model other elements as well? An example of the former would be say the Atlanta or Waterloo campaign, or an intensive action between naval, land, and air forces in the Solomons in World War Two, while the later can be the entire courses of wars, such as The Punic Wars, the Thirty-Years War, or at the extreme end the "International Wargame," where each player is king of a country and diplomacy takes place between the players with shifting alliances, economics, and even political and social factors.

Focus defines, within the scope of the campaign, what features and facets you will model. What is it that interests you about the campaign, and what things or actions (out of the whole range of possible phenomena a commander must deal with in war) will the game model and the players experience. These ideas of scope and focus are very important for without careful attention to these, the game will become too huge and complex or too narrow and bland. It will also determine many of the control procedures and tools that will be used.

If you are doing a campaign like Jackson's Valley battles, very little in the way of economics or replacements, production, or diplomacy, in fact none, would be appropriate as none of these things were a useful or worthwhile consideration. Nor was Jackson himself concerned with these things. On the other hand, at the International Wargame level, small scale unit tactics and the fine differences between this regiment and that, and the differences between small unit tactical doctrines become trivial and meaningless. In the mid-range of campaigns, the Valley Campaign, or The Solomons for instance, the characteristics of historical subordinate commanders are not a factor as the gamers play these roles each bringing his own individuality to the game. In an International Wargame these characteristics are a factor as there usually will be no real-life characters to assume that role.

Scope and Focus also determines what exactly is being modeled, or more important, why are you engaging in the campaign? It must be more than "I've got a whole bunch of these clowns painted up!" Some factor, incident, process, or the like must have drawn you to it, and it will be that factor that you want to model and expend a lot of detail on, while other aspects are necessarily abstracted. For example: If you are fascinated by the dogged determination of the Rebels to hinder the Federal advance on Atlanta by tearing up railroads, burning bridges, blocking tunnels, and raiding supply convoys, and the just as dogged determination of the Federals to repair, rebuild, and resupply, then the campaign you will form will be quite different than a mere map and order of battle.

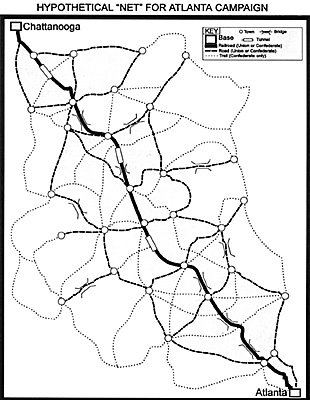

Consider the HYPOTHETICAL CAMPAIGN MAP for the Atlanta Campaign below. You will not be refighting, Resaca, Kennesaw Mountain, or Cobbs Farm. Indeed these clashes of the main armies can be abstracted or ignored, and reflected merely as the movement of a line representing "the front" up and down the railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta. The forces used will be small detachments of infantry and cavalry scattered around a road-rail net, garrisoning important bridges and tunnels, or escorting supply convoys. The Union will move on this net, as will the confederates, but the Confederates will have another "net" which they can move on as well. In the illustration shown as an example, it would be the fine dotted lines as opposed to the railroad or roads. Again, this is merely conjectural and does not represent any real places or geographic features.

If the Confederates occupy a town, blow a tunnel, or burn a bridge, the line must move back one or two spaces, and the Union commander will be faced with garrisons, small expeditions to cut off access roads and nodes to guard against Confederate infiltration, laying traps etc.

An example ofthe wrong way to pay attention to Scope and Focus is the SPI game "Campaign in North Africa" put out some 20 years ago, which needed a bowling alley to set the map up on, and which had every unit down to trucks in counters, and you had to specify the loading of each truck unit (with food, ammunition, water, or fuel etc). Obviously someone caught on that the key to the situation in North Africa was supply, but theen took it to the extreme. The game should have been more properly named "Company Clerk in North Africa."

What is important in all this is to keep in mind that you must. abstract the details or those parts of the campaign that are not significant, and emphasize, (out of all proportion sometimes) those that are.

Scope and Focus thus between them "generate" the campaign idea.

Then What?

The next thing is to do some preliminary 'gedenktexperiment" and figure out what the campaign will look like, what it will do, and if you are satisfied by that. Let's take the foregoing hypothetical Atlanta campaign. Do you want to game with a map that looks like that? Do you want to refight lots of small actions between a regiment or two of infantry and a gun, and two regiments of cavalry and a baby-howitzer? If, after carefully considering this you decide that you really want Resaca, Kennesaw, and Cobbs Farm, then, you don't want to do this campaign. What you want is a game about the effects of raiding and interdiction on front-line operations. Another example of this is the old Avalon Hill Game of LUFTWAFFE. It is an excellent example of a game that has its focus and scope cast correctly. The map consists simply of general political boundaries and strategic bombing targets. In actuality that's all you are concerned with. It's really a pretty good game, however, when the game came out, however, it was pretty much a dud. The reason was simple, the map was not what most wargamers had come to expect. Where's the Rhine? Where's the Black Forest, the Ardennes, the Carpathians, the broad Russian steppes, the broad Russian rivers? Where are the Panzer Divisions, the mobile Flak units? Why isn't the Wolfschanze marked? Why isn't there a mountain of dun-brown units glacially moving forward, pushing the small little "feld-grau" pebbles ever slowly backward, and suffering titanic attrition in the process, calving off huge "dun-brown" icebergs which are surrounded and digested by groups of those feld-grau pebbles? In short what people expected to see, they did not see, which really meant they really didn't want a game about strategic bombing, they wanted a game about the EFFECTS of strategic bombing on operational and strategic military operations. This of course is not Avalon Hill's fault- they put out a very good game about strategic bombing, which no one really wanted. When you make a campaign you do not have to operate under the same liability or make the same mistake. Nor can you afford to. Avalon Hill had the entire gaming world to draw customers or interested people from. You have only your immediate group of war-gaming people.

Scope and Focus thus will deal intimately with the game materials and control procedures. It will also have a lot to do with another major factor of the campaign - interest. Just what and who the players are, and what are their responsibilities? Also are they going to share your vision? Do they want a campaign about Strategic Bombing, or do they really want a game about the effects of strategic bombing on day to day operations, which means not moving a line up and down a map of North Georgia, or in ticking off strategic targets, but having your Volksgrenadieres scrambling around for clips for their Schmeissers and not finding them because the B-17's blasted the cartridge factory back in Boomennbangen. The best way to do this is with a campaign outline, which will lay out what the campaign is about, what materials it will use, how it will be played, and what the players will deal with, and circulating it around. See the example outline for a hypothetical campaign "Scourge of God."

Now circulating this among the group will give them a good idea, and quickly too, of what the game will be like, put some proto-typical game materials in their hands, and give them a more balanced presentation than you breathlessly blathering on about it at a game meeting. Now my extremely strong suggestion is that you take note of the phrase at the bottom of page 2. You will notice that it says "If you are interested in participating in this campaign, please sign here, and mail it back to me at..." I would urge you to insist on this and allow no exceptions. No verbal agreement, e-mail, fax, handing it to you at the meeting - but good old snail mail.

My reason is simple. If the person isn't willing to put himself through the trouble of signing it, addressing it, putting it in an envelope, stamping it, and dropping it into the mailbox, odds are he's not going to do the work required to participate in a campaign, especially where he's likely to have to do just that process to mail in his moves! It's a test of commitment.

Returning to another issue related to scope and focus. It will also determine not only what actions and phenomena your players/generals will have to deal with, but it will determine what range of knowledge and background they must be equipped with. The major question here is how far do you want to "stretch" your players, have them confront new situations, possibly do research, but certainly get into new ground. If the campaign is in an area with which they are very familiar then it won't be much of a stretch.

A good example of this is an advanced politico-econo-military game like CIVILZATION (the computer game by Sid Meyer, not Avalon Hill's Civilization or the computer game of that game). It is a highly detailed, intense, deep and challenging game, and for the first dozen or so iterations you are really exploring new territory, finding out what works, figuring out the processes, and getting thoroughly schlonged in the process, even if you've bought the wildly overpriced cheat-manual. As with all computer games though, once you master the basics, your play gets better and better, until some time down the road, you are regularly beating your computer opponents at even the highest levels. The reason is simple. You have figured out the "logic" of the game, and can work the rules to wring maximum advantage.

What I am describing here is really two phases The first is sense of wonder/sense of danger, and the second is sense of achievement/sense of victory. In the first you're not usually interested in winning, just surviving and not doing too badly. You are more enthralled by the eye, ear, and mind candy the machine is displaying, and thinking "neat". The game catch is the visuals, the challenges, the sense of anxiety and danger in the unknown. This is entirely different than a game where players can work expertly, exploiting all sorts of canny moves and long, detailed and convoluted strategies of enormous subtlety. Here the reward is glorying in your own virtuosity and brilliance.

Yet as overdrawn as my examples are, they are essential for you musk ask, at the same time you send out the game, what your players want to play. Simply saying "I want to do a campaign about the Mediterranean theater of World War II" is inadequate. One person will see sand-flecked Panzers snaking across the desert, another will see Italian Battleships steaming boldy forth to sea, and a third will see The Luftwaffe, like the white troops in a colonial game, coming along to help the poor benighted third-world type Italian Reina Aeronautica and show em how its done, not your view of paratroop and amphibious operations against Crete, Rhodes, Malta and Pantalleria.

It is equally important when crafting a campaign and thinking about scope and focus, is the individual players in the group. I have partially alluded to this, but any gamer must think about several factors related to the gamers. Just as it is important to make sure you have troops and terrain suitable, you have to have players who are suitable as well. Here you must ask yourself many hard questions.

Are they cheaters?

This can mean out-and-out dishonest types who consider cheating and avoiding apprehension as part of the game, or those who think it's ok to bend the rules and take every advantage so long as it is not specifically prohibited. All campaigns run on an honor system to a lesser or greater extent, and how ethical your players are will determine how much checking and record keeping you will have to do. It will directly impact your control procedures and how you report the game.

I remember once running a play-by-mail campaign in which players sent in their moves. They were required to send them in filled out with ink, but one player always sent in his filled out in pencil. When something happened that he didn't like he simply changed the orders and said I had made a mistake in reading it. When I stopped this by echoing (in ink) his order on the form, he began doing it in ink, but kept several sets of alternate orders which he would then send in. I eventually caught him and threw him out of the game, but this is not always a solution you can enact in a group of friends as I could in a commercial play-by-mail game. Nor can you always say "Hey Alf... you can't play in this campaign because... well... your a cheat!" Control procedures to prevent and catch cheaters become very cumbersome.

Supercompetitors are also an issue. If your players are overly competitive, you will have more trouble than if they are cheaters. Not from errors or mistakes, but from highly detailed orders, enormously complicated moves and a manic micromanagement to wring every possible advantage, and exclude all possible chance. And endless arguments when something goes wrong as to why it just couldn't have gone wrong! This is worse than cheaters because it's not illegal in any sense of the word. Here your control procedures might be made very workable by using broad based, "net-effects" and not allow the detailed micro-management, but if so you will have the problem that that may not be the game your players want.

Laziness is unfortunately the worst. If your players simply won't do the work, put in the effort, and take the time, there are no control procedures or processes that you can put in place that will force them to do so. If majority participation in a campaign is required, then it is sure to fail if too many players are lazy. I once thought that I had cured this by instituting a fairly good set of procedures and iterations to apply, a set of policies as it were, to situations where a player was hit with a bout of sloth. This would carry on the game without the necessity of his sending in every move, and, I thought, would serve for a turn or two.

Unfortunately I soon found out that it worked too well, and worse I had turned the lazy player into a highly competitive one (though one who worked incognito). He would not send in his moves, would not come to the games, but would complain bitterly about what his "subordinates" (the cardboard characters I had set up to represent the decision makers that would take over in his absence) and their decisions, and how HE would have done it much differently. Worse still, when a battle was taking place, he most often was not present, but would call for hourly updates as to how his troops were doing. The piece de resistance was when I finally told him that I was dropping him from the game for laziness, he complained and said that it was my fault because I had designed a game which did not give the players enough control or things to do to keep them busy."

I suspect the man went on to a brilliant future as a CEO.... brilliant in the sense that he had a magnificent golden parachute when he rode the company into the ground.

Johnny One-Notes These are guys who are interested in one thing and one thing only, and anything else will leave them cold. One has to have a general tolerance for all gamers, and a general willingness to acquaint ones self with them to play campaigns. Forming a campaign on the Conquest of the Aztec Empire and counting on a player who is fanatically interested in World War II Eastern Front WWII is doomed to fail. Likewise, a person who is always going on about SS Panzer troops is going to become fixated on the workings of the 443rd SS Volksturmgrenadier messkit repair battalion to the detriment of... say... the Luftwaffe. Once again the campaign will have to be carefully crafted around these players. Remember you are pretty much stuck with the players you got.

Win lover This type of gamer is also very dangerous to a campaign. A Win lover is fine when the game starts and will be eager and attentive, and seemingly a joy to have. Once things don't go their way, or once he suffers a slight reverse he loses interest fast and his complaints will start to mount, and his participation decline in inverse proportion. He will start talking about other games, other things to do, and will generally turn ineffectual, indifferent, and incognito in short order. It's not hard to spot these gamers, but you will have to allow for them if you craft a campaign with them.

Another important thing that must be dealt with in scope is what determines Victory and Defeat? When will the game end? Assume you want to make a Grand Campaign about the Second Punic War. What will be the conditions of victory given that such conditions may not be directly relatable to the events of the battlefield? Is it to be when Rome or Carthage is taken? Will it be a time limit after which Rome is determined to have won (if Rome is not taken) and Carthage is exhausted. The Death of Hannibal? Loss of a high enough percentage of casualties? This is not always so easy. A group wishing to do the Campaigns of Alexander would have to face the fact that they were dealing with a potentially unstable individual,. There is no reason to believe that if he had conquered China, would he have stopped there? He very might have well decided he was going to conquer the Kamchak's, Aleuts, and what was later to Become the Maya, work his way through Greenland, and conquer the Britons, Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Romans from the other way around!

Finally in the largest sense, for example, an International Wargame, where each player is the king of a country, Victory in any meaningful or calculable sense may be meaningless. That is, to assign a victory condition may be impossible, even something as simple as "conquer the world." In cases like this a time limit may be the key, or merely engage in it as "an experience" rather than a competition.

Having gone so far, it is easy to see how scope and focus impacts every point of the game, and why you must pay careful attention to it.

Cost

There is one thing I want to also bring under the heading of scope. This is a part of the game almost always ignored or given little attention by gamers, and that is cost. The effort of a campaign is going to cost money. It's going to cost money for postage, or for paper, reproduction, game materials etc. This is where you must carefully plan various facets of the game.

If, for example, you were going to use the Avalon Hill game 1776 as the basis for the campaign game, well and good... but do the rules require that EVERY PLAYER has a copy? Will they buy it? Is it Available? If the game, for example, relies, upon a vector movement system, how much postage will be involved in the shipping and movement of overlays and reports. You might say that E-mail is the easy way to get around this, and so it might, but how much will you move over the net, and once again, there is a cost in time, and perhaps even in dollars to taking up so much time. This can be a hard issue to broach. Back in the days before The Net, when we sent everything by "snail-mail" it was not uncommon for players to bristle when I asked them for reimbursement for postage. Their attitude was that they were paying postage to send the stuff to me, and did not consider that each of them was paying for only himself, but the umpire would be paying for all 12 of them (to send the moves and reports back, which was more paper and hence more postage). Most of them seemed to think that I should do it gratis out of "good buddy" feeling. My own thought is that if you are the umpire and coordinator you're already sacrificing a lot.

This is a hard thing to broach, and once again goes back to the "interest" issue of the gamers. Everyone is eager to play a game. Once the costs come due... it's often a different story.

More Campaigns or Campains?

Scope: What are you trying to do? What are you trying to model, and what is the "hook" or interest in the campaign?

Knowledge and Background

Hard Questions

Victory and Defeat

Campaigns or Campains: Introduction

Campaigns or Campains: The Proctor System

Campaigns or Campains: Vector Movement System

Campaigns or Campains: Scourge of God Outline

Campaigns or Campains: Control Method Comparison Table

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #78

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com