COMMENTARY

How did the Romans maneuver and relieve successive lines while in combat? The ideas developed by historians are varied.

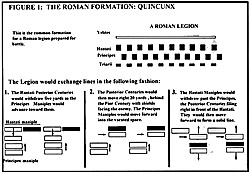

Some writers believe that the legion's maniples actually fought with gaps 20 to 40 yards wide between them because this is how the quincunx formation begins a battle (see figure 1).

Some writers believe that the legion's maniples actually fought with gaps 20 to 40 yards wide between them because this is how the quincunx formation begins a battle (see figure 1).

Personally, I can not imagine the legion fighting with ten gaps in their line, leaving half the enemy line un-engaged. All ancient armies obsessively worked to present solid lines facing the enemy, and the problems of small 120 man units being so separated make it an impossible idea to me. Such a combat line would have been so unique that Polybius, Livy, and others could not have failed to comment on it as they did other unusual traits of the legion formation such as the "ordos" relieving one another.

My ideas on the subject derive from Connolly, Healy, and others. The quincunx was a maneuver formation, primarily designed to allow the lines to relieve one other. Each maniple was originally positioned with the 60 men of the Posterior Century behind the 60 men of the Pior Century so they could relieve and be relieved in battle (bottom of figure 1).

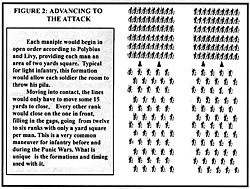

Maniples would form up in open formation. This gave each legionnaire two yards around, enough room to throw the pila. The beauty of this formation is that it seems to echoe the

quincunx of the Legion, for the same reason. The back lines close the gaps of the front lines by moving two paces forward. (see figure 2.)

Maniples would form up in open formation. This gave each legionnaire two yards around, enough room to throw the pila. The beauty of this formation is that it seems to echoe the

quincunx of the Legion, for the same reason. The back lines close the gaps of the front lines by moving two paces forward. (see figure 2.)

Large Figure 2 Diagram: (slow: 104K)

From the ten lines twelve deep of the typical Speira in a phalanx, the maniple could go to six lines in close order for melee. With the Roman shields thirty inches wide, this would allow a foot between each shield or scutum for the thrust of the short sword.

What the actual rank formation of the maniple was never documented, but for the Triarii it has been. Polybius says the Triarii maniples were only 60 men strong and drawn up in three ranks. Armed with spears, this would be a close order formation.

As the entire purpose of the Triarii was to cover a retreating line, it would have to have the same length front as the larger maniples of Hastati and Principes. This means three ranks with a twenty yard front for the Triarii maniple. This requires the other Maniples to fight and move with the same frontage, and thus a depth of six ranks, keeping the twenty yard front.

The actual maneuver to form a solid front is the same maneuver that would be carried out to relieve each line. When moving to engage after throwing the pila, the Hastati would close, each century now only 20 yards wide and six yards deep. For the Posterior century to move to the left and forward would require each soldier to move about sixteen yards. This could be easily done in 30 seconds, especially if rigorously practiced as the legionnaires were.

To be relieved, the Posterior century would reverse the process. Once it had moved back behind the Pior century, the Principes Maniple would move forward, filling the gap as the Hastati maniple retired. When the Hastati maniple had past, the Principle Posterior century would move right and into line as had the Hastati.

Ranks

There is an argument that the Pior and Posterior referred to privileged rank and not actual position. While the Pior centurion did outrank the Posterior centurion, these two Roman military terms were not typically used when referring to a rank precedence of individuals or units. I side with the historians that hold the meaning to refer to the position the centuries. Rank would still go to the Pior century beawse it was the anchor of the Maniple, first in and last out in the relief maneuver. The real issue is how this could be done during combat. There were several things that made it possible:

1. The Roman discipline. The legionnaire was one of the best drilled soldiers in the Ancient world. The maneuver could be done very quickly. There are several stories of Generals killing their own sons for breaking formation to charge the enemy, though the stories could have been for instruction purposes....

2. The large shields of the Maniples could create walls on the very narrow flanks exposed (3-6 yards) as well as for the moving Posterior Century. All movement of the Posterior Century in both the Hastati and Principles maniples when engaged would be to the right with the legionaires' shield arm always facing the enemy.

3. The Ancient armies fought in rigid lines. A hoplite or pike phalanx would not be willing to take advantage of the temporary 10 yard gaps in Roman lines because it would break their own formation. As long as the legions faced the Italians, Greeks and Carthaginans, the line relief procodure would encounter few problems.

However, light and medium infantry in the form of Celts and Iberian swordsmen was another matter. They were willing to "break formation", charging ahead to fill in the gaps created by withdrawing centuries and attack the marginal flaoks of those who remained. The relieving maniples would have to fight their way forward to relieve the Pior centuries. It was the barbarian warbands that presented the greatest problems for the Manipular Legion according to Connolly and others. The necessity of facing the Germanic Tribes helped force the development of the cohort legion.

From my playtesting of the rules modifications given above, you will find the Roman legions much more unique and formidable on the game table as well as more historically relevant. They will allow you to use both Varro or Scorpio's formations and maneuvers with no complicated rules. They also will make "historical sense" as they do not in the rules now. You may find that Varro's mass phalanx of legions very effective given the right circumstances....i.e. no Carthaginians within a day's march. Enjoy.

REFERENCES

Game (Rule Set), Publisher

Ancient Empire, The Emperor's Headquarters

Ancients, Peter Pig

Ancients Rules, 7th edition, Wargames Research Group

Armati and Advanced Armati, Wargames

A to Z Rules Ancient Warfare, Andrew Zartolas

Axe and Arrow, Gamescience

De Beilis Antiquitatis, Wargames Research Group

De Bellis Multitudinis, Wargarnes Research Group

Fast Play Ruks For Ancient Warfare, Newbury Rules

Rencounter, Ed Allen

Robert's Rules of Warfare, Jawbone Communications

Rudis, Tabletop Games

Swond & Shield, Tabletop Games

Tactica, Quantum Press

Wargamer's Guide to Ancient Combat, Z & M Publications

Bibliography

Caven B. The Punic Wars. London 1980

Connolly, R Hannibal & the Enemies of Rome, London 1978

Connolly, R Greece and Rorne at War, MacDonald & Co. LTD 1988

Gabba E Republican Rome, the Army and its Allies, Blackwell, 1976

Healy, M. Cannae 216 BC, Osprey Campaign Series #36 1994

Head D. Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars, Wargames Research Group 1982

Lazenby, I.F. Hannibal's War. Warminster 1978

Livy, The War with Hannibal trans. A. de Selincourt, Penguin Classics, 1965

Polybius, The Histories of Polybius, trans. E. S. Shuchburgh, London 1889

Sekunda N. Early Roman Armies, Osprey Men-At-Arms Series #283 1995

Sekunda N. Rcpublican Roman Army 200-104 BC, Osprey Men-At-Arms #291, 1996

Watson, G.R. The Roman Soldier, Thames and Hudson 1969

Wilcox, R Rome's Enemies 2, Gallic and British Celts, Osprey Men-At-Arms #158 1985

Wise, T. Armies of the Cartheginian Wars 265- 146BC, Ospery Men-At-Arms #121.

Specific Rules Modifications and More

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #73

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com