Long before drug running precipitated the United States invasion, Panama

attracted scoundrels interested in making easy fortunes. During the heyday of the

Spanish empire, Panama was the transshipment point for the silver of Peru on its

way to Spain. The vulnerability of the overland trail through Panama lured many

pirates wishing to milk the wealth of Spain.

Long before drug running precipitated the United States invasion, Panama

attracted scoundrels interested in making easy fortunes. During the heyday of the

Spanish empire, Panama was the transshipment point for the silver of Peru on its

way to Spain. The vulnerability of the overland trail through Panama lured many

pirates wishing to milk the wealth of Spain.

Morgan attacks a Spanish ship. Models are from Mini Figs heavily detailed by their owner, Orv Banasik who took the photos.

English corsairs used the cover of constant wars between Spain and England to pillage the Spanish Main. When Charles II made peace with Spain in 1667, privateers in his colony of Jamaica ignored the treaty and continued their depredations. Charles didn't impede them, for Prize Law granted him and his brother one sixth of their booty. So long as they filled his coffers, he overlooked their treaty violations. A notorious treaty violation occurred in 1671, when Henry Morgan, the most successful corsair, descended on Panama with 2000 sea dogs packed in 38 vessels. Because England and Spain were at peace, his raid had to be profitable to the crown if he wished to keep his head.

The President of the Audiencia de Panama, Don Juan Perez de Guzman,

expected the privateers. Their noisy preparations had spread alarm throughout the

audiencia. Don Juan had few assets for resisting them. He had a few hundred

Spanish regulars and a couple thousand militia. Many of them had never fired a

gun, but that hardly mattered, for their equipment was often inoperable in the

tropical humidity. The Indians, free blacks, and half castes in Panama did provide

an excellent scouting service for him.

The President of the Audiencia de Panama, Don Juan Perez de Guzman,

expected the privateers. Their noisy preparations had spread alarm throughout the

audiencia. Don Juan had few assets for resisting them. He had a few hundred

Spanish regulars and a couple thousand militia. Many of them had never fired a

gun, but that hardly mattered, for their equipment was often inoperable in the

tropical humidity. The Indians, free blacks, and half castes in Panama did provide

an excellent scouting service for him.

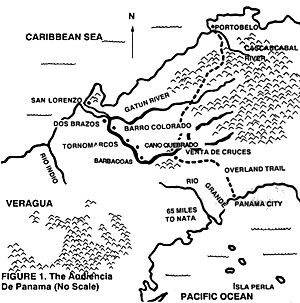

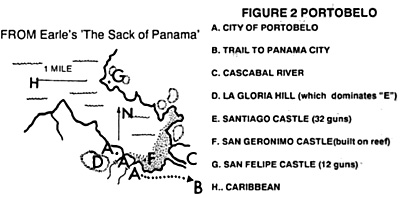

The geography of the isthmus was the one factor which seemed to favor Don Juan (Fig. 1). Most of the isthmus was wild, hilly jungle, perfect for the guerilla fighting at which his Indian allies excelled. One land trail crossed the isthmus from Panama City to Portobelo, and Portobelo was protected by three stone fortresses (fig. 2). Further up the coast, the Chagres River cut two thirds of the way across the isthmus. It's outlet to the Caribbean was guarded by the Castle of San Lorenzo (Fig. 3).

Don Juan planned to repel Morgan on the Caribbean coast. He placed 140 militia and 360 regulars in Portobelo, and he threw 310 militia and the remaining regulars into San Lorenzo. Lest Morgan bypass San Lorenzo, he strengthened the defenses of the Chagres by erecting stockades at Barro Colorado, Tornomarcos, Cano Quebrado, and Barbacoas and garrisoning them with 450 men.

Portobelo was too strongly fortified to attack, so Morgan sent Joseph Bradley

and 470 men to capture the harbor at the mouth of the Chagres. Guarded by two six

gun artillery platforms and an eight gun tower at sea level, and dominated by the

Castle of San Lorenzo de Chagres perched on a cliff above, the harbor was too

strong to be taken by Bradley's three small ships. If he could take the castle, the

harbor would fall into his hands.

Portobelo was too strongly fortified to attack, so Morgan sent Joseph Bradley

and 470 men to capture the harbor at the mouth of the Chagres. Guarded by two six

gun artillery platforms and an eight gun tower at sea level, and dominated by the

Castle of San Lorenzo de Chagres perched on a cliff above, the harbor was too

strong to be taken by Bradley's three small ships. If he could take the castle, the

harbor would fall into his hands.

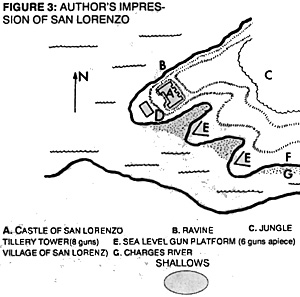

Bradley's men landed down the coast from San Lorenzo, marched up the beach, and scaled the heights of San Lorenzo. The castle was a strong stockade with four landward and two seaward bastions. It's walls were formed by double palisades with earth packed between them, and an overhead palm canopy shaded the defenders. In front of the walls, a 30 foot deep ravine made a natural moat. It was spanned by one drawbridge. The field in front of the walls had been cleared of brush.

The Spanish were alerted and well armed. Bradley had a low opinion of the

Spanish, so he ordered frontal assaults on the castle. The first two assaults were

easily repelled; the third was more successful. A grenade ignited the stockade's

palm canopy, and a Spanish cannon exploded, blowing a breach

in the stockade and creating a bridge of debris across the ravine. The

Spanish militia scurried down the cliff to their canoes, but the regulars fought

until they were exterminated the following morning. Five days later, Morgan

appeared with the main fleet. He spent a week repairing the castle and left

300 men to hold it.

The Spanish were alerted and well armed. Bradley had a low opinion of the

Spanish, so he ordered frontal assaults on the castle. The first two assaults were

easily repelled; the third was more successful. A grenade ignited the stockade's

palm canopy, and a Spanish cannon exploded, blowing a breach

in the stockade and creating a bridge of debris across the ravine. The

Spanish militia scurried down the cliff to their canoes, but the regulars fought

until they were exterminated the following morning. Five days later, Morgan

appeared with the main fleet. He spent a week repairing the castle and left

300 men to hold it.

Advance

On January 19, he began the advance of Panama City by sailing up the Chagres with 1500 men crammed into seven small ships and 36 boats. The timid and poorly armed Spanish deserted and burned their stockades at his approach. Above Barro Colorado, the river was too shallow for the ships, so 200 men were left to guard them. The remainder continued their march in the tall grass that grew on the river banks, with supplies floating beside them in canoes. There were a few skirmishes, but more men were lost to hunger and sickness than Spanish attacks.

On January 25, Morgan reached Venta de Cruces. Rugged terrain replaced river jungles. It was perfect territory for ambushes, and Indians attacked several times. Morgan responded by sending out advance parties. When an advance party collided with Indians, flank parties worked around them to cut off their escape. The privateers overcame all the ambushes and emerged from the jungle on their eighth day out from San Lorenzo. Ahead of them stretched a broad savannah leading to the golden city.

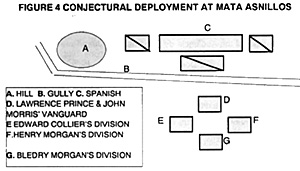

Pandemonium reigned in Panama City. Scared citizens were fleeing to the jungle or Ecuador. Don Juan, however, resolved to defend the city. He had hoped to repel Morgan in the hills near Venta de Cruces, but the militia deserted his prepared position. He gathered them at a new battle site about a mile outside of Panama City, the field of Mata Asnillos. The field seemed suited to his poor forces. With no artillery, his 1200 infantry and 400 cavalry were incapable of maneuver, poorly armed, and of the lowest morale. He hoped his foot, arranged in a line about 200 yards long and six men deep, could disorder the English with gunfire so that his horses could ride them down. A hill on his right anchored his line, but he placed no men on it.

Morgan advanced in four divisions of about 300 to 400 men each (Fig. 4). He

had no idea of the training and morale of the Spanish, but he saw that they

outnumbered him and had the pikes and cavalry he lacked. Clever tactics would

have to overcome their perceived advantages. A gully ran across his front, and

Morgan ordered his forces into it. There, out of sight of the Spanish, they crept to

the hill. The Spanish mistook Morgan's vanishing into the gully for a retreat, so they

broke formation and pursued. Morgan's men raced up the hill and fired into them.

The Spanish cavalry bolted for Panama City. After another privateer volley, the

Spanish infantry broke. The privateers followed closely, killing anyone they caught.

For the cost of 15 men, Morgan had killed or wounded 450 Spanish.

Morgan advanced in four divisions of about 300 to 400 men each (Fig. 4). He

had no idea of the training and morale of the Spanish, but he saw that they

outnumbered him and had the pikes and cavalry he lacked. Clever tactics would

have to overcome their perceived advantages. A gully ran across his front, and

Morgan ordered his forces into it. There, out of sight of the Spanish, they crept to

the hill. The Spanish mistook Morgan's vanishing into the gully for a retreat, so they

broke formation and pursued. Morgan's men raced up the hill and fired into them.

The Spanish cavalry bolted for Panama City. After another privateer volley, the

Spanish infantry broke. The privateers followed closely, killing anyone they caught.

For the cost of 15 men, Morgan had killed or wounded 450 Spanish.

The survivors tumbled into Panama City and joined the exodus of citizens; they made no attempt to defend the barricades that had been built in the streets. Don Juan had previously arranged the mining of the buildings, so Panama City was a ruin when Morgan entered it. The privateers scoured the ruins in search of loot. They fought the fires, searched the ashes, and tortured their prisoners to find Panama's legendary riches. When their tally was complete, they were dismayed by the lack of treasure found in the rubble of the putative golden city. Alas, the Spanish had spirited away most of the wealth. Morgan did capture a small barque and used it to raid nearby coastal communities and islands. A little more booty was added to his haul, but the largest share of Panama's treasure was out of his reach.

Fear of Spanish reinforcements from Colombia or Peru obliged Morgan to depart Panama on March 16. He absconded with treasure valued at £ 30,000 and about 600 prisoners, most of whom were sold into slavery. The raid was not as profitable as past attacks, but King Charles II was satisfied with his share. He needed to present some pretense of offense at this raid upon his ally, so Morgan was arrested and hauled to London in April 1762. He was lionized by society, knighted by the king, made advisor to the king of Jamaican affairs, and named Jamaica's governor three years later.

As for Panama, the audiencia rebuilt itself. Its regeneration was slow, for Morgan had taken most of the slaves. Panama City was rebuilt on the Peninsula of Ancon, six miles from the old city and thought to be more readily defensible. And upon that peninsula Panama City has securely pursued its commerce ever since. Securely, that is, until a couple of years ago, when a clever invader repeated history by toppling an unprepared foe.

Morgan's Sack of Panama 1671

- Historical Background

Wargaming the Sack

Campaign Rules

Large Map (slow: 156K)

Jumbo Map (extremely slow: 464K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #58

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com