The largest army yet assembled on the North American continent was in disgraceful retreat. Heavy casualties among those regiments which or six hours had assaulted the abatis on the high ground before Fort Carillon spoke eloquently for the courage and determination of the British and Colonial soldier. But those same soldiers had run panic stricken to their boats. They had abandoned their wounded to the savages.

Four days later, on July 12th Major General Abercrombie held a Council of Was at his camp at the head of Lake George. What should his army do, now that the victorious Montcalm had been reinforced from Canada? Another try at Ticonderoga did not have much appeal.

Now arose Lt. Col. John Bradstreet of the Regulars. Born at Halifax in 1711 of a British officer and French mother, he was commissioned Ensign in the Regulars, and supplemented his pay with a small vessel he owned. This he used to smuggle contraband into the French fortress of Louisbourg. In 1745 he used his knowledge of the place during the siege, and won a Captain's commission. Now he was commander of the batteau-men and their vessels, and as Deputy Quartermaster General, charged with the transportation of supplies for Abercrombie's force. Not a glamorous position for one who sought glory and advancement, but certainly a necessary task.

He had won glory! The army of 15,000 had been transported from the head of Lake George to Carillon, 32 miles distance, over night; the troops resting on their oars. Bradstreet had seen to the prompt and orderly unloading of supplies during the two days the army was before Fort Carillon. After the British defeat, he had re-embarked much of the stores, most of the wounded, all the survivors, and got them safely back to camp at the southern end of Lake George.

Clearly Bradstreet was capable of organization and execution. He was a leader of men. Now he would prove to be a persuasive advocate of his own plan for victory and advancement.

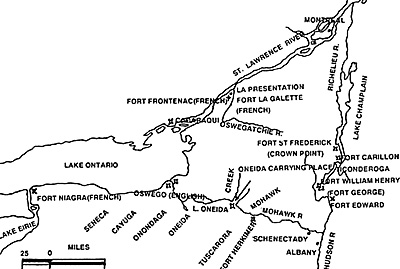

He reminded the assembled officers of a previous council early that spring, wherein his plan for a sudden descent upon a surprised Fort Cadaraqui (Fort Frontenac to the French) had been agreed to. He summoned to his support the hero of the army: "The deceasd Lord Howe, who excells in penetration and judgement, highly approved of the scheme". As Howe had been killed in the late attack none could dispute this point. His plan would also protect the Mohawk Valley from French raids by building a fort at the Oneida Carrying Place, replacing the forts destroyed during the Panic of 1756 following the fall of Fort Oswego to Montcalm.

Bradstreet was opposed by his enemies, by the envious, those having schemes of their own, and a timid General shaken by his own recent defeat. Yet "...After warmest opposition; ... by a majority it was carried in the affirmative."

The very next day, July 13th, 1758, General Orders warned troops detached from the main army to be ready to march. The New York Regiment of two battalions was first, leaving camp on the 14th. The New Jersey Regiment marched on the 15th; then the Rhode Island Regiment; Doty's Massachusetts Regiment and finally, the Artillery. By the 20th the New Yorkers were at Schenectady, and four days later the tail of the expedition caught up. Here the troops would prepare for the next stage of the expedition: the advance to the jumping-off place on the frontier. In Schenectady the troops were admonished as early as July 21st:

- "Notwithstanding the Orders Against the Soldiers Going Into Town Getting Drunk, they still Continue Disobeying. Its Repeated Orders that Whosoever is Found in Town Or In Camp Drunk Will immediately Receive Two Hundred Lashes Without the Benefit of A Court Marshall".

The transport of barrels of flour and other supplies would be done in bateaux, or "Schenectady Boats". These were mass-produced in that town every winter, used for a campaign or two until they fell apart or were destroyed by military action, and then replaced. The men would march west up the Valley on the road which ran beside the bank of the Mohawk River, driving their beef cattle with them.

Each bateau was about 32-36 feet long, 3 to 4 feet in the beam, had a draft of 3 to 4 feet, and could carry 3 to 4 feet, and could carry fourteen barrels of flour or salt meat, for a total burthen of about 2,800 pounds. Crews were generally 3 or 4 men who poled, rowed or sailed the craft. By now they were specialist employees of a semi-civilian Bateaux Corps; laborer-boatsmen, but they were armed and presumably drilled. Bradstreet will use them to further his own glory as a corps de elite.

In all, the expedition used at least 123 bateaux, and the Corps included 270 men. Further, the water in the river was very low at this at this time of year; The men often having to get out and unload the barrels onto sandbars, haul the bateaux over, and then reload them on the up-river side. Bateaux were best used in the early spring, when the snow-melt made for "high water".

Meanwhile, William's Regiment of Massachusetts troops garrisoning the Mohawk Valley was sent forward to Fort Herkimer. This was the palisaded home of Mr. Harchheimer, one of the principle inhabitants of the frontiers, who were Palatine Germans. A large stone dwelling house, it had numerous out-buildings to shelter neighbors and their carts and animals in case of Indian attack.

The commander at Fort Herkimer was Lt. Colonel Clinton of the New York Regiment. He was ordered to advance to the "Oneida Carrying Place" and fortify the ruins of Port Craven. His part consisted of William's Bostonians; two companies of his own New Yorkers; and two companies of rangers, probably raised in New Hampshire and Boston.

By August 10th the rear had arrived at the Carrying Place. Now began a laborious task.

- "The waggons which had been brought from the settlements on the Mohocks river, were immediately employed in transporting batteaus, whaleboats, provision, etc. to Fort Newport, where a guard was ordered for their security. "

By the 11th, Brigadier Stanwix of the Regulars was able to draw from each regiment quotas "of such men as are most accustomed to water." These were:

- Regulars of the Independent Companies 155

Rangers of Independent Companies 60

The New York Regiment 1,112

William's Massachusetts Regiment 432

Doughty's Massachusetts Regiment 248

The Rhode Island Regiment 318

The Jersey Regiment 412

Plus 270 Batteau-men and 42 Indians.

Total for the Expedition 3,049

The whole to be under the command of Colonel Bradstreet, and to be ready "with everything compleat, and six days provision, tomorrow evening".

Let us pause to review the campaign on the eve of departure. First, it was a secondary effort. It was born of the defeat of the main force. And it had in it something of the nature of a sop, or a gambler's last desperate throw.

Also, it was executed with remarkable speed. Permission was given on July 12th, orders were issued on the 13th, and troops marched on the 14th. Here was no ponderous, supply-heavy expeditio of the type seen thus f during this war. Unlike previous expeditions, Bradstreet did not wait to gather all his forces in one place; he did not wait until all his supplies had arrived. He marched troops in daily sequences; he sent advance parties on to prepare for later arrivals; he continued to bring up supplies after the main force had left. With his energy, Bradstreet united mental flexibility.

Finally, this was an American expedition. Only 155 men wore the red coats of the Regular Independent Companies. At this stage of the war, even many of these men must have been Americans; but diverse all the same. The New Hampshire Scotch-Irishman was far removed from the German Lutheran of New York's Ulster County, or the New England Congregationalist. These were even further removed from the Irish Catholic immigrant and the Long Island Indian serving with the New York City companies.

There were two other items of business to be attended to at the Carrying Place. First, Bradstreet was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Regulars. DeLancy, Williams, Doughty and several other Provincial officers were full Colonels, holding their Governor's commission and out-ranking him. How could command of this expedition be given to an officer so junior in rank? Yet the King's business must go forward.

There is no record of the council of war held by Brigadier Stanwix, yet it had to have happened . The Provincial Colonels must have been persuaded to set aside their own rank, under the pretense that as quotas of troops were drafted from their regiment, not the entire regiment, then they had no claim to the prestige of commanding an expedition of quotas. Instead they, and the younger, older, and less healthy men, stayed at the Carrying Place to build Fort Stanwix, a new fort guarding the Carry and the settlements on the Mohawk River.

This question of regular versus provincial rank was one of the most vexing questions faced during the French and Indian War. The Regulars soon learned how to make a beach-head landing, to train and use Light Infantry, and to send expeditions deep into Indian Country. Yet they never developed a rank structure that recognized the abilities of a capable and experienced colonial officer; nor paid tribute to the fact that most of the men in any expedition or camp were colonials; nor acknowledged the contributions of colonies heavily taxed to pay for the large numbers of men they strained to put into the field each campaign. Many of these disgruntled American officers would later serve in the higher ranks of the Revolutionary Army.. (indeed, Lt. George Clinton, son of Lt. Colonel Clinton of the New York Provincial Regiment, would be the Revolutionary Governor of New York State. Captain Marinus Willett would aid in the defense of a rebuilt Fort Stanwix against his former British comrades of 1758, and play a major role in the 1777 defeat of Burgoyne's expedition.)

The other task, (perhaps ordeal might be a more fitting word,) was to meet in council with their Indian allies. Sifting in the sunny August heat, with gifts and rum liberally supplied from the King's magazine, the Officers listened at length to the Chiefs. Then, of the 150 or so warriors gathered there, there, only 42 could be persuaded to take up the hatchet. One can hardly blame the Iroquois for a lack of enthusiasm in backing the efforts of their British allies. Thus far the Regulars had been defeated at the Monongahela in '55, at Fort Oswego in '56, at Port William Henry in '57, and at Fort Carillon a month past. Now they proposed to attack a Port which had stone walls!

But of much more importance was an "up to the minute" situation report from one of Bradstreet's special "assets." In this savage congregation, Colonel Bradstreet found his friend Red Head, an Onondaga chief: a man of high reputation and distinguished abilities (among the Indians).

Red Head had recently visited Fort Frontenac, and was allowed to wander through the defenses and then depart. Dealing with Indians was always a tedious business of giving presents, persuasion and protocol. Any unknown Indian was a friend. Good manners required that friends be invited inside, their questions answered, that they be fed, and wished "good speed" on their return home, even if their home might be in the enemy's land.

European officers on the frontier must have ruefully contemplated the difficulties of dealing with the Indians. No doubt all Indians looked alike to them. Perhaps they complained because once bought, you couldn't trust Indians to stay bought. Bradstreet must have wondered: was Red Head telling him what he thought Bradstreet wanted to hear? Could this former "French" Indian, now be trusted?

Thus far Bradstreet had to contend with men, Now Mother Nature was his opponent. The troops, boats and supplies gathered at the ruins of Fort Bull, the source of Wood Creek (i.e. the stream which flowed west towards Lake Ontario, not east to the Atlantic.)

- 'In its natural state, it can only with propriety be call'd a brook or rivulet, as it has not sufficient depth of water to float even an empty batteau; but the grounds from whence it is supplied, being low and marsh, abounded with springs, and surrounded with small eminences; a dam was thrown across, by which a body of water is collected; the boats being put into the creek and loaded; are kept in readiness, and whenever a sufficient quantity of water is gathered, the sluice is open'd which conveys them to the next dam."

"The want of water, detained our boats all night ... but a plentiful rain falling towards day, on the 15th they were brought down to us. "

The expedition was on it's way!

By the evening of the 16th all of the troops were joined at Spack Bergh, four miles beyond Canada Creek

- "which we gained with the greatest difficulty ... meeting with the utmost obstructions from the trees, which had fallen across the creek, and in many places entirely blockd up it's passage: these we were obliged to cut away... "

"The lands on each side are low and very rich, covered with large timber; they likewise abound with poisonous shrubs and woods of various kinds: the falling of whose leaves, impregnate the ponds and rivulets with their unwholesome qualities; hence, these waters are not to be drank without manifest bad effects; indeed, / observed that most of the men ... who were obliged to be so continually in the water, had the skin entirely taken from their feet, in which a very high inflamation was raise'd".

By the evening of the 18th the troops had traveled 56 miles, 38 of them that one day. Now they were at the head of Oneida Lake, a large body of water twenty miles long. Tomorrow would be "smooth sailing." Yet here things started to go wrong.

Some friendly Indians told them of a fishing party of seven French Oswegatchie Indians who had left the day before,

- "who were gone forwards to Cadaraqui, but we could not learn, they had

any intelligence of our approach. We were in pain for a scouting party who Colonel

Bradstreet had sent forward from Bull's Fort, to reconnoiter the country as far as

Oswego. "

Now the expedition was in a race against these lightly traveling Indians, who might easily arrive at Frontenac two or three days before they could. The garrison would be alerted; but much worse, they would send for help from the Canadian militia near Montreal. Bradstreet would have to hurry his siege, lest he be surprised by three or four thousand Canadian militia.

The next day the expedition reached the falls of the Oswego River after passing an island on which were the bodies of two lads, servants to the officers of the scouting party. They were clothed. A large fire still burned. Killed without torture, perhaps the Indians had not gotten from the lads the news of the expedition. The Oswegatchis could not be very far ahead of the expedition.

Yet here was the 8 or 10 foot high falls, followed by a mile of rifts. On the morning of the 20th, all disembarked save four men to a boat. Dragged across the 50 yard portage, the loaded boats were sent down the rapids. The mile was traversed in three minutes, but several boats were stove in, including one bateau with a cannon and a mortar aboard. These were raised into other boats. The next day saw the portage completed, the boats repaired and caulked. That night the expedition camped on the Lake Ontario shore near the ruins of Port Oswego, destroyed by Montcalm two years before .

On the morning of the 22nd the expedition

- "reviewed our arms, drew ammunition, cookd three days provisions, and at eleven o'clock embarked."

First came the Indians and Rangers in whaleboats. Then came the Bateaumen and provincial detachments also in whaleboats. Next were the Regulars in bateaux, followed by the New York and New Jersey troops also in bateaux. The Train was in the center, followed by the Massachusetts and Rhode Island Troops in the rear of the main body, also in bateaux. The rear guard was in whaleboats. Crossing Lake Ontario in 95 whaleboats and 123 bateaux, the water was calm, the wind favorable, and the troops rowed until 2 a.m.

High wind and waves the next day slowed progress, and that afternoon the advance whale boats discovered and fired upon five Indian canoes, which made their escape. At 2 o'clockthe next morning, "four discharges of cannon at Cadaracqui, were distinctly heard, our distance from thence being about fifteen miles."

The expedition was discovered, but if the weather cooperated, it was too late to benefit the garrison. The weather did not cooperate, keeping the flotilla ashore until 4 p.m. though only five hours rowing from their objective. The troops rowed to within six miles and were again forced ashore. Now within sight of the Fort, the expedition waited until evening, when the wind dropped and they could finally cross to the mainland, landing without opposition.

It must have been nerve racking to all, to be in sight of their objective for two days, yet helpless to attack, and knowing that the same wind which hampered them, helped the French courier speeding down river, to fetch the relief expedition from Montreal.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #57

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com