The Rangers and Indians "scoured the woods & reconnoitered the Fort whilst the whole army was formd in the front of their boats." The French fired 50 rounds of cannon, but the troops lay that night upon their arms, covered by rising ground before them.

Bradstreet's force "stood to" two hours before daylight, but the garrison did not sortie. The boats were moved to a sheltered anchorage, the artillery was landed, the high ground west of the fort was seized, and "the major part of the army were now immediately ordered to make fascines and gabions." Bradstreet reconnoitered the ground.

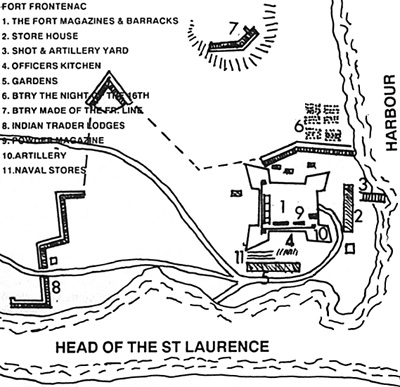

With only 70 rounds per cannon, only 40 spades, spades, pickaxes and shovels, he could not think of a long siege. Particularly with the Canadian militia gathering. He resolved to seize that very night an old breastwork 250 yards south of the Fort. He would cut embrasures in it for two cannon and three howitzers. This was too far away to be his real attack. Yet it would serve as a decoy.

Meantime, Bradstreet and his engineer officer would take advantage of a slight rise of ground 150 yards west of the fort, and erect a small fascine battery and dig shallow trenches to cover the men. Although the enemy kept up a continual firing at their noise, the night was very dark and only a very few wounded resulted. Six hundred men (1 company Regulars, 7 companies New York Provincial Regiment & Bateau-men) occupied the rising ground on the west, "each man carrying a fascine, and two pickets on his shoulders, together with his arms.

"A French sortie failed to find the 600 men to the west. The fort was diverted by firing at the old breastworks, garrisoned by 600 men from the Rhode Island, New Jersey and Massachusetts regiments. Dawn saw the besiegers entrenched, with two 12 pounder guns emplaced. From farther away, the howitzers played upon the place. "They did considerable damage to the inner part; one [bomb] burst near the magazine, and fired a quantity of gunpowder, which scorched some of the Indians almost to death, and greatly intimidated the garrison."

What of the garrison all this time? Messieur de Noyon, the commander of the fort, had been given two crumpled pieces of paper found on the island where the "fishing party" had murdered the two lads. He deduced what was about to happen, and promptly sent a canoe to Montreal with an appeal for help. Governor Vaudreuil, whatever else his enemies might say about him, promptly called up 1,500 militia, which marched the very next day from Lachine. It had taken just five days to summon help.

But the defense was not as well managed. The only sortie did not find the working party in the dark night. The counter-battery fire was ineffective. The bombshells disheartened the garrison of 110 souls, of which only 50 were soldiers.

Finally, the stone walls were only three feet thick at the base and two feet thick at the top. The terreplein was a wooden platform supported by tall posts. Every time the garrison fired a cannon, the fort shook! Impervious to the muskets of a raiding force, the walls were easily smashed by the 12 pounders of Bradstreet's battery.

The garrison certainly remembered the massacre of the British prisoners in 1757 at Fort William Henry. Were the British tuning the tables? Did they have Indians themselves? Could they control their Indians? Prospects for the garrison did not look good.

Between 7 and 8 in the morning, the French hoisted a red flag and their drum beat a parley. All firing stopped. Since the French national flag was white with golden fleur de lys, their flag of truce had to be some other color: in this case, a soldier's red jacket.

Mr. Sowers, the Engineer officer was allowed into the fort, (no doubt to observe all he could while inside, in case resistance should continue). But he did relay Bradstreet's terms. First the carrot: the garrison might keep their money and clothes. They would be paroled and allowed to go to Montreal to be exchanged, rather than taken as prisoners of war to Albany. Next the stick; Bradstreet would only wait ten minutes for an answer!

The bluff succeeded, for the French had enough. The only dockyard fleet base on the Great Lakes; the great storehouse of their Indian trade; the most important of their chain of posts to the West. All this would be given up after a feeble resistance of only two days. Casualties were very light for both sides.

One hundred and ten persons were taken, while forty sailors aboard the vessels escaped ashore. Also taken were eight Indians, three burnt almost to death.

The fort was garrisoned by Captain Ogilvie and the two companies of Regulars, and for a good reason. Bradstreet trusted neither his own plundering provincials, nor his own Indians.

Bradstreet took pains to keep the Indians away and assure the French that they would not suffer the same fate as the garrison of Fort William Henry when Montcalm was unable to prevent an Indian massacre of prisoners.

The amount of plunder was enormous. A snow, a brig, three schooners, two sloops, and all their rigging kept in the great warehouse were taken. Also taken were 60 pieces of cannon, 16 mortars and 6 brass patereros. These were largely the spoils of Braddock's defeat, and the capture of Port Oswego. Also taken was "a prodigious quantity" of Indian trade goods: at least 10,000 barrels of it, or 800,000 Livres worth, amounting to 35,000 pounds sterling. Finally, the victors took much of the year's crop of furs from the west.

By the evening of the 28th the plunder had been sorted out; the smaller vessels burnt; the two largest sent off to Oswego filled with plunder; the great warehouse (200' by 25') and wharf destroyed; and the walls of the fort pulled down and it's buildings destroyed.

By midnight of the 30th, Bradstreet's expedition returned to Oswego. The two French vessels were burnt, and the heavily laden bateaux, with a double crew of 8 each, could not make their way up the stream. With much labor the exhausted and sick army arrived at the ruins of Bull's Fort on August 8th. Here a division of the plunder was made. Every man, officer and private alike, shared equally. It was an ample reward for their labors.

Why was the raid successful? In his own pamphlet history of the expedition, Bradstreet spells out his reasons. They seem simple, indeed simplistic to us today. But remember, these conditions had not yet been present in British North America."

"The principal foundation of a successful enterprise against this fort, was aid in the information Colonel Bradstreet had received..." ' That is, the eyewitness accounts of Red Head and perhaps other Indian spies, beginning early in the year and continuing to the very eve of the expedition.

Bradstreet knew that the fort was lightly garrisoned, unprepared and poorly commanded. Bradstreet knew that the French Lake fleet, which might easily have blown his whaleboats and bateaux out of the water, was laid up "in ordinary" to save money; with most of the rigging ashore in the warehouse.

Bradstreet immodestly claimed other "requisets, essentially necessary in the conduct of enterprizes in the American wilds, together with those characteristics which have ever distinguished the greatest generals": Caution and secrecy; the greatest expedition in marching; judgement in making a proper attack without bloodshed; intrepidity and resolution.

Was this an idle boast? First, none of Bradstreet's men poised at Oswego knew whether he would attack Fort Niagara, Fort Frontenac, or the French Indians at Oswegatchie (Ogdensburg, N.Y.).

Next, Bradstreet's force traveled 225 miles in 10 days, with an additional four days lost to rough water, and of course the additional labor of four days during the siege and destruction siege and destruction course the additional labor of four days during the siege and destruction of the fort. This was indeed, "the greatest expedition in marching".

Finally, Bradstreet had scanty supplies of ammunition and tools, yet compensated for this by a bold, close-in attack, using the abandoned earthwork

to decoy the enemy. The swiftness of both his approach and his siege made it impossible for the 1,500 Canadian militia to gather and meet his 3,000 in battle. Despite the greater number of Britons I feel the Canadians probably would have won. The Britons had achieved their goal: capture the fort and plunder it. Their thoughts were on the "getaway" and not further fighting. On the other hand the Canadian relief column was thinking about speed, revenge, and wresting away some of the plunder for themselves..

Bradstreet's raid is little more than a paragraph in most general histories of the war. There was "little bloodshed" to add color. There was little blundering to permit the historian to pontificate, nor allow the casual reader to feel superior. Yet the results of the expedition were of great importance at the time.

Bradstreet's victory deprived the French of their Lake Fleet. It deprived them of their grand magazine of the Indian Trade. It aided the construction of Fort Stanwix at the Oneida Carrying Place which protected the Mohawk settlements for the rest of the war. It encouraged the Iroquois and disheartened the French Indians. At Easton, Pennsylvania that October, a treaty brought peace to the frontiers of that province, Jersey and Virginia.

The sight of plunder in the packs of the survivors, must have encouraged recruiting for the successful campaign of 1759. In the long run, what was thepsychological result on the minds of those American officers who had done so well without the guidance of the professionals? Bradstreet continued to boast:

What of Bradstreet? What was his reward? His American enemies, paticularly those in the Indian Department demeaned the Regular's achievements and said anyone might have done the same. The British were reluctant to praise the Provincials when the Regulars had done so poorly, From this moment of glory, Bradstreet's star dimmed. The Regulars were learning to do better, and within a year English churchbells would ring joyously for those lasting heros of the war: Wolfe and Amherst.

Wargamer Aspects

What are the important aspects for the wargamer? First, I have commented on how much Bradstreet knew about conditions at his target. Perhaps the gamer's view of his opponent's force laid out on the table within sight isn't always the unrealistic situation we think it is.

Secondly, Mother Nature must be considered: fallen trees, low water, high waves, sickness, etc. The most difficult task of the campaign was getting to the objective. A map-based exercise with dice throws or chance cards to move your forces might not be very exciting, but it would certainly be authentic in the forest warfare of the period. It would provide the unexpected event, throwing an opponent off balance and offering golden opportunities to the bold player.

Next, consider what might have happened had the Canadian militia been alerted three or four days earlier; or if only one of the French warships had been cruising. Caution, planning, valor; all would be for naught and Bradstreet's fate would have been at the whim of that fickle goddess, Fortuna.

How utterly useless were Bradstreet's Indians! Except for Red Head. Yet Indians were necessary despite their expense and the trouble of keeping them happy. If the whim took them, they could strike far and fast. Indians could protect a column by their far ranging scouts. In short, they allowed wilderness expeditions to attain "woods superiority".

Bradstreet attained artillery superiority by transporting only a very few rather light siege guns (12 pounders) and an insufficient quantity of ammunition, to a spot where the French never expected to have to resist such guns. Their fort was "hardened" against the only likely enemy: raiding savages or parties of Rangers. Two 12 pounders and three howitzers were easily enough for the mission.

Volunteer on the Expedition; An Impartial Account of Lt. Colonel Bradstreet's Expedition to Fort Frontenac, London, MDCCLIX

America Provincials moving inland to attack the French. Miniatures are 30mm Willies and Staddens and 25mm RSMs. The building is The Trading Post scratch built by Miniature Service Center. From the collection of Bill Protz. Photo by James J. Marsala.

America Provincials moving inland to attack the French. Miniatures are 30mm Willies and Staddens and 25mm RSMs. The building is The Trading Post scratch built by Miniature Service Center. From the collection of Bill Protz. Photo by James J. Marsala.

"All except five or six, kept at a miles distance during the attack, came running from the woods, where they had been concealed like ravenous beasts, full of the expectations of satiating their blood-thirsty fury on the captives."

"These advantages have been gain'd without putting the Crown to a hundred pounds sterling extraordinary charge."

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PRINCIPLE SOURCES USED

Gipson, Lawrence Henry;The Great War for the Empire, Volume VII, New York,1965 Godfrey, William G.; John Bradstreet's Ouest, Montreal, 1983

Hamilton, Edward P.; The French and Indian Wars: the Story of Battles and Forts in the Wilderness, Garden City, NJ 1962

Hewlett, Captain Richard;"An Orderly Book Kept by Captn Hewlett' MS #1 2744,New York State Library

O'Callaghan, Edmund B.; Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Vol. X. Albany, 1858.

Preston, R.A. and La Montagne, Leopold; Royal Fort Frontenac, Toronto, 1958

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #57

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com