December, 1942. Seven Soviet armies hold the German Sixth

Army, a quarter million men, encircled and trapped at Stalingrad.

Additional Soviet forces push hard against the allied armies on the

flanks, threatening to break through to Rostov and cut off all German

forces in the Caucasus. The Germans struggle to supply their trapped

men, put together a force strong enough to punch through the

encirclement, and hold the Soviets at bay.

December, 1942. Seven Soviet armies hold the German Sixth

Army, a quarter million men, encircled and trapped at Stalingrad.

Additional Soviet forces push hard against the allied armies on the

flanks, threatening to break through to Rostov and cut off all German

forces in the Caucasus. The Germans struggle to supply their trapped

men, put together a force strong enough to punch through the

encirclement, and hold the Soviets at bay.

For three weeks, the German 48th Panzer Corps fought against the Soviet 5th Tank Army at the Chir River, west of Stalingrad. In spite of the strategic disaster, the 48th Panzer Corps successfully held the lower Chir River positions, revealing a decisive superiority in tactics and operations over the opposing elite Soviets. The Panzer Corps, however, would break off and end the battles by being forced to retreat to retrieve the strategic collapse that developed on its left (northern) flank at the end of December 1942.

The Background: 22 June 1941 to 19 November 1942

The Germans attacked the Soviet Union on 22june 1941, moving out of the edge of darkness at 0305 in Army Group North and 0315 in Army Groups Center and South into furious battles with surprised and confused Soviet troops. The Red Army resisted stubbornly; the communist bureaucracy directed a prodigious mobilization; and the European Russian theater of operations with its unpaved roads, forests, swamps, and rivers, proved a formidable challenge to German offensive mobility. Interpreters of the war give these factors as the ones largely responsible for the German defeat.

The interpretation is unconvincing, however, because the German Army overcame those factors and inflicted terrible casualties and damage onthe Red Armybringingit to the edge of defeat by 4 August 1941 at the conclusion of the Smolensk battle of encirclement. During that time, and later in the greater battles at Kiev, Vyasma, and Bryansk, the Germans would establish a psychological ascendancy over the Soviets that continued to the end of the war. This German sense of superiority and the parallel efficiency of German tactics and operations are fundamental for any understanding of the German defensive successes on the Chir River later in the war.

The higher leadership of the German Army envisioned defeating

the Soviet Union in European Russia by destroying the Red Army

while simultaneously advancing into European Russian space fast

enough and far enough to paralyze Soviet mobilization. Colonel General

Franz Halder, Chief of Staff of the German Army from 1938-1942, with

elegant simplicity, demanded a main drive toward Moscow. He

articulated the idea that the Soviet government would be forced to

defend Moscow as the capital, communications, and manufacturing hub

of European Russia with the main concentration of the Red Army.

[1]

The logic is impressive: if the Soviet high command committed

the preponderant strength of the Red Army in the defense of Moscow,

it followed axiomatically that (if committed) it could be destroyed at the

time (August 1941) and place (in front of Moscow) of German

choosing.

In summary, Halder, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, the

formidable commander of Army Group Center, and virtually every

other German army officer associated with higher level decisions in the

attack against the Soviet Union, foresaw the destruction of the Red

Army in front of Moscow in August 1941.

[2]

They also saw German occupation of Soviet mobilization space

far enough to the east of Moscow to win the war. The German field

armies advanced so effectively in the 17 weeks of Operation Barbarossa

that it can be generalized that they in fact possessed the capabilities to

have brought the war to a successful conclusion roughly within that

time period.

German troops of the 7th Panzer Division in Panzer Group Hoth

arrived 50 miles east of Smolensk cutting the main rail line and highway

connecting it with Moscow on 15 July 1941, a scant 24 days into the

campaign. Army Croup Center had mastered both time and space in

European Russia so decisively that the army group was prepared, by

approximately 12 August 1941, to advance directly at Moscow and the

mobilization space lying in an arc to the east of it. They army group

would have attacked with every division originally in the advance still

intact and operating at about 70 percent of its original striking power (of

22 June 1941), [3]

with a rail and logistics system capable of supporting it to significant

distances beyond Moscow. It can be stated categorically that on

approximately 12 August 1941, the Soviet field armies had little realistic

capability of slowing Army Group Center and none of stopping it.

By that date, the Soviets had mobilized an additional 29 divisions

from the still functioning mobilization space of European Russia and

placed them around Moscow where they represented a powerful (final)

strategic reserve. That reserve also would have had little chance of

survival against approximately 55 intact,

veteran German divisions advancing into the same area.

Adolf Hitler, after epic procrastination and against the advice of

the army, instead directed Army Group Center into an eccentric

operation into the Ukraine. Hitler strategically misdirected his army into

defeat during the month of August seeking indecisive objectives -

indecisive in the sense that Hitler's objectives could not be equated with

the defeat of the Red Army and the collapse of the Soviet political

system.

Herein lies the pattern that would repeat itself in the great

summer campaign of 1942, the autumn battles around Stalingrad, and

the episode on the Chir River in December 1942. The German Army,

even though strategically misdirected into defeat in the war in August

1941, would continue to operate with devastating effect against the

Soviet armed forces. The German Army would consistently display

tactical and grand tactical superiority in combat against the Soviets

[4] while descending into a pattern

of strategic misdirection.

Battle Superiority

The battle superiority of the German Army in European Russia

is difficult to exaggerate. The army in 1941 conducted movements and

inflicted casualties and damage that exemplify the paradoxical situation

in which the German formations on the Chir River in December 1942

would defeat strong Soviet forces advancing against them while

simultaneously being forced to withdraw at the end of December

because of the disintegrating strategic picture.

The achievements of the German Army in the summer and

autumn of 1941 are reflected in operational disasters for the Soviets

from which they have not yet managed to disentangle themselves

psychologically. Those disasters are exemplified by the following

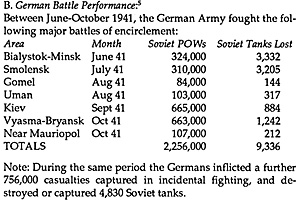

historical data:

Note: During the same period the Germans inflicted a further

756,000 casualties captured in incidental fighting, and destroyed or

captured 4,830 Soviet tanks. The German Army thereby captured approximately 3,012,000

Soviet armed forces personnel and permanently removed 14,166 tanks

from the order of battle. The Germans probably inflicted an additional

2,000,000 casualties in killed and permanently disabled: a total of some

5,000,000 Soviet troops removed from the armed forces. These

casualties are part of the historical record and exemplify the tactical and

grand tactical ascendancy of the German Army in the Russian campaign.

The fact that the Germans did not win the war against the Soviet

Union after inflicting such casualties in so short a time period is

explained by the Olympian strategic misdirection of the German forces.

The parallel fact that the Soviet armed forces took almost four years to

emerge on the winning side in World War II with powerful British and

American military forces is explained to a significant degree by the same

German superiority in tactics and grand tactics - the capability of the

Germans to win battles in war. 6

Directed away from Moscow in August 1941 because of Hitler's

preoccupation with the seizure of Leningrad and the Ukraine, German

field armies with the mobility and striking power to get to Gorki, or

possibly even Molotov under the "army plan", rampaged through the

ample Russian countryside. They did so from June-October 1941, but

to no decisive end. Given the opportunity to recover, the Soviet high

command continued the mobilization of the armed forces, concentrating

them almost entirely around Moscow.

In November 1941, therefore, in spite of the previous loss of

5,000,000 men, the Soviets were able to set up adequate defenses

between the Germans and Moscow, while simultaneously putting

together a strategic reserve capable of counterattacking the misdirected

German forces of Army Group Center. The Soviets launched a strong

offensive early in December 1941 against the German field armies

around Moscow that continued through the winter of 1941-1942.

Combined in an unlikely way with the erratic decision of Hitler to lay

siege to Leningrad and a successful Soviet counteroffensive of more

modest dimensions against Army Group South, the Soviet winter

operations around Moscow stabilized the situation on the eastern front

to the benefit of the Soviets through the spring of 1942.

As spring approached in that year, the German Army High

Command began to redeploy the field armies in the East for continuation

of the advance into the Soviet Union. Continuing the pattern of high

level misdirection of the German Army, Hitler demanded an offensive in

the South with the strategic goal of seizing the Caucasian oil fields. He

wanted to improve the economic situation of Germany, under siege

against the armed forces of Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United

States (after 11 December 1941).

With a strategic style inadequately explained to the present day,

Hitler had no intention of attacking and defeating the main concentration

of the Red Army now massed south and southeast of Moscow. Faced

with a German offensive in the South, the Soviets had not quite the

physical strength (numbers), or the organization (perfected tank and

mechanized rifle armies), or the

self confidence in command to attempt to seize the strategic initiative

from the Germans in the summer of 1942. With amazement similar to

that in August 1941, the Soviets saw the Germans heading southeast,

i.e., in a direction utterly indecisive from the viewpoint of the defeat of

the Red Army and associated fall of the Soviet government.

Hitler again misdirected the German Army in 1942, but it

continued to show the virtuosity in winning battles that gained so much

respect for it in World War II At Izyum, the 6th Army destroyed the

Soviet forces in their spoiling attack of May 1942, and at Sevastopol,

the 11th Army, in a completely different style of battle, battered its

way into the fortress in the most successful siege operation of World War II.

German Offensive

Then, in July 1942, three German field armies plunged toward

peripheral, distant targets in the Soviet Union, allowing the intact Red

Army to continue to reinforce itself north of the Don undisturbed. The

Germans would present the intact Soviet forces with a long, exposed

flank offering a wealth of opportunity for counterattack. Prepared to

defend themselves in the crucial heartland area between Moscow and the

middle and upper reaches of the Volga River, the Soviets found

themselves spectators to three German field armies marching blithely

past the main concentration of the Red Army on a 600-mile move that

would put them deep in the north Caucasus and close to the Caspian Sea.

In accordance with the special Russian style of holding back

strong reserves for final contingencies, the Soviet High Command had

concentrated huge forces for the defense of the center area of European

Russia. Those forces now became available to take offensive advantage

of the eccentric German move into the Caucasus.

[7]

The Soviet High Command had learned the danger of encirclement

from advancing German forces in 1941; now, with the loss of well over

5,000,000 men by the spring of 1942, they could no longer afford to

trade casualties for time and space in which to survive. The Soviets

directed a skillful disengagement of their forces in the path of the

advancing Germans. During this disengagement, the Soviets for the first

time in the war traded space for time.

As it became apparent that the Germans were headed for the

Caucasus and Stalingrad, the Soviets were presented with hundreds of

miles of thinly populated space in which to avoid the Germans while

simultaneously preparing defenses closer to the oil fields and continuing

to concentrate and reinforce a vast, untouched force north of the Don

River. The Soviet High Command had survived into 1942 and had begun

a grand reorganization of the army that can be broadly characterized as

follows: [8]

1. The unwieldy 1941 infantry division of 14,000 men and two

artillery regiments was converted into smaller 1942 divisions with

approximately 10,000 men and one artillery regiment.

2. Tanks continued to be diffused among tank, mechanized,

motorized, and infantry organization in special tank regiments and

brigades. Only by the end of 1942 did powerful, balanced tank armies

emerge, capable of conducting deep, grand tactical drives.

3. Artillery tended to be concentrated in independent regiments

and artillery divisions that were employed in major operations, e.g.,

along main axes of advance selected by the Soviet high

command. The German summer offensive, beginning in July 1942,

developed in a front from Kursk in the north to Taganrog on the Sea of

Azov in the south. Hitler directed the main weight of the offensive

southeast towards Grozny, not far from the Caspian Sea on the north

slopes of the Caucasus Mountains. To execute Hitler's strategic

directive, the German Army High Command deployed the powerful

German 17th Army and 1st Panzer Army under Army Group A for the

attack into the Caucasus.

Stalingrad

To protect the northern flank of the advances into the Caucasus,

the high command directed the strong German 6th Army and several

weaker allied armies eastward along the right (south) bank of the Don

River into its great bend, jutting far away to the East. The 6th Army

became the spearhead of the drive into the bend of the Don, and, as it

arrived there by 25 July 1942, it almost incidentally became drawn

farther cast toward the large (population approximately 500,000)

industrial city of Stalingrad, lying 90 miles away on the right (west)

bank of the Volga. Possessing only a few strategic attributes in its own

right, Stalingrad became, part by accident, part by design, the focal point

of one of the decisive battles of World War II.

Strategically, Stalingrad was no Moscow, but as a symbol, it

acquired commanding proportions.

[9]

The Soviet High Command instinctively massed powerful forces

to defend the city and Hitler ordered its seizure (23 July 1942), directing

parts of the relatively weak 4th Panzer Army, operating on the north

flank of Army Group A, away from the Caucasus and toward Stalingrad.

Hitler, with his predilection for fanatical preoccupation with

tactical situations, concentrated the 6th Army on a narrow front against

Stalingrad and pinned down that mobile formation in a battle largely

extraneous to the strategical goal of seizing the oil producing areas

farther south. Had the 6th Army deployed instead on a broad front in the great bend of the Don in a flexible, mobile defense of the north flank of the German forces attacking into the

Caucasus, it probably could have successfully checked the massive

Soviet forces that were ultimately employed there. Hitler played into

the hands of the Soviets by fixing the 6th Army around Stalingrad, and

the Soviets committed powerful forces to the defense of the city under

ideal circumstances for the rigid style of the Red Army - the defense of

a large industrial city lying along a major rive barrier.

The main concentration of the Red Army meanwhile lay

undisturbed north of the Don in August-October 1942 and was

gradually reinforced by powerful strategic reserves previously held back

for any contingency in the European Russian heartland south and

southeast of Moscow. On 4 October 1942, Marshal Georgi K. Zhukov

and General Aleksander M. Vasilevskiy, representing the Stavka (the

highest Soviet military planning and executive group), headed a

conference that initiated planning for a Soviet counteroffensive at

Stalingrad [10] that would

exploit the strategic situation using the patiently concentrated reserves.

In Uranus, the code name for the Stalingrad counteroffensive, the

Soviets would employ largely the new, more controllable 1942 infantry

divisions and the new tank armies behind strong concentrations of

artillery flexibly tailored for each offensive, but inflexibly controlled in

accordance with rigid time tables for breakthroughs.

The German Army High Command warned Hitler in strong terms

during August 1942 about the dangers of a Soviet offensive across the

Don River from the area in which the stronger northern envelopment in

the Stalingrad encirclement developed. The Chief of Staff of the German

Army, Colonel General Halder, railed at the untenable position of the

6th Army so strongly, and was so critical of inadequately-screened

operations into the Caucasus, that Hitler removed him from his position

on 25 September 1942.

At the strategic level, the German Army had become the prisoner

of its self-willed, often brilliant, but fundamentally siege-oriented

dilettante supreme commander. Hitler proved willing to present an

exposed flank of vast proportions in order to include the Caucasus

within his uniquely circumscribed siege space. The German Army found

itself in a bizarre situation that can be generalized as follows: four

German field armies advanced between 300-600 miles into the southern

periphery of European Russia and then into Asia. They did so with the

near-certainty from the beginning of the operation that they would have

to recoil back to protect their own flank from the intact main

concentration of the Red Army.

In summary of the period July 1941-October 1942, it can be

generalized that a German Army capable of defeating the Soviet Union

in a brief campaign of 10-17 weeks in June-October 1941, was used

instead to assure the seizure of the occupied Baltic territories and the

Ukraine. Roaming through the ample Russian countryside in 1941, the

German field armies exhibited a marked superiority in both command

and combat soldier style. Hitler strategically misdirected an instrument

capable of winning the war in 1941 into failure in the war.

Hitler then misdirected the same instrument capable of

maintaining the initiative for the Germans in the east in 1942 into the

loss of the strategic initiative in November 1942 and accompanying

severe operational setbacks. The apparent contradiction, i.e., the

Germans winning battles all over European Russia while in the process

of losing the war after August 1941, is explained by the immense gap

between Hitler's strategic diffusion of the German Army in the

campaign and the German Army's superiority in tactics and grand

tactics (operations) over the Red Army.

For purposes of understanding the Chir River battles, the

summary above provides a picture in which the elite German 48th

Panzer Corps (11th Panzer Division, 336th Grenadier Division and 7th

Luftwaffe Field Division) lay embedded in a strategic disaster taking

place all around it.

Chir River Battles Dec 4-22 1942

Soviet assault troops, Stalingrad front

Soviet assault troops, Stalingrad front

A. German Mobility in European Russian Space:

A. German Mobility in European Russian Space:

Panzer Group Guderian moved 1,400 miles (straight-line

distance) between 22 June-30 November 1941, most of the distance

against strong resistance. The distance is the same as that from Brest-

Litovsk to Molotov (Perm) in the foothills of the Central Urals.

Soviet Reorganization of the Armed Forces (1942)

Introduction and Background

Immediate Preliminaries: 19 November - 4 December 1942

Chir River: 4 - 22 December 1942

Battle of Sovhkoz 79

Battle of 19 December: Kalinovski

Orders of Battle: German and Soviet

Large Maps (5): extremely slow: 494K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 3

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com