In 1900, England was the greatest power on the globe. Queen Victoria, who would die the next year, had grandchildren on the thrones of Germany and Russia, as well as various minor states. The sun never set on the British Empire, which included India, nearly half of Africa, Canada, Australia, and many other possessions around the world. Almost half the invested capital in the United States was English. The English navy had converted the oceans of the world into British lakes.

England's great enemies were France and Germany. Both of the latter aspired to be naval powers. This was perceived to be the greater threat in the case of Germany, since German naval power would perforce be felt in the North Sea, an approach to the British Isles about which the English were very sensitive. In addition, both were in competition with England for colonial possessions in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. France was perceived as the greater threat here, because of her already extensive holdings in the areas named.

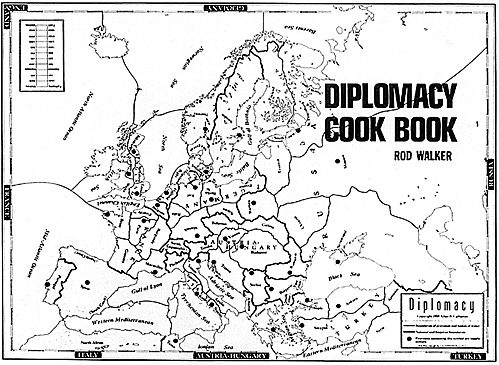

In Diplomacy, England's only concern is Europe, and the colonial question does not enter into it. Even her European colonies, Cyprus, Malta, and Gibraltar (not to mention Irelandl are on the board. In order to win, she must get a toe hold on the continent against any or all of Russia, Germany or France. For the discussion that follows, the reader is referred to my first article, on Austria, for the key to symbols and the organization of the article.

England's Opening

One game-year's sail from England, several tempting supply centers persent themselves: Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, and Brest. Despite this, however, England's obviously superb defensive posture is offset by a very limited offensive capability. Of all those centers, all save one can be reached in Spring 1901 by other powers or protected by them against England in Fall 1901. The one exception is Norway, but even here, if Russia moves his A Moscow-StPetersburg in Spring, he can stand off an unsupported English attack in the Fall; and if France, Germany, and Russia cooperate against England, as sometimes (rarely) happens, England may be kept out of Norway even if he supports himself in. In all of this.

England's best hope is peace with France. Trying for Brest (F London-English Channel) is foolish at best, because it will antagonize France and France may have desired peace with England. Therefore, England's best opening is to concentrate on Norway and holding the the North Sea approach.

The best moves for the opening are: F Edinburgh- Norwegian Sea, F London-North Sea, and A Liverpool- Edinourgh. This pos~t~on gives the greatest flexibil ity in approach ing Scandinavia. London can still be defended if the French precipitously move to the Channel. In the meantime, England gives himself a choice ot puttmg an army or a fleet in Norway. If an army, he has a choice as to which fleet convoys, thus potentially freeing the F North Sea to take a role in the struggle over tne Low Countries.

England's most important decision is how to take Norway. There are three important possibilities:

-

1. Take Norway with the army, convoyed by F Nth,

and moving F Nrg-Barents Sea. This threatens both

Sweden and St. Petersburg, and heralds a general

assault on Russia when Russia has not moved. A

Mos-StP. A variant of this is to move F Nth-Nwy, F

Nrq-Bar. but it is a very weak offensive and hardly

worth the effort.

2. Take Norway with the army, convoyed by one fleet and supported by the other, This again is anti- Russian, generally undertaken when Russia has ordered A Mos-StP. It is more defensive in character, but indicates a desire to carry the war to the Russian homeland. It may also be undertaken when England is not yet certain what France and Germany are up to (1 indicates England thinks France and Germany are going to war or have interests elsewhere).

3. Take Norway with one fleet, supported or not by the other The support may be to ward off the Russians, but in either event, England's intent is to give Russia as little cause for fear (or suspicion) as possible.

If England's F Nth (or F Nth and A Edi) are free to meddle in Continental affairs, they could take the form of standing German out of Denmark or Holland, but usually means that England is either supporting France or Germany, against the other, into Belgium. There are times when England is able to take Belgium himself. However, in an alliance with France or Germany with England, the Continental ally naturally expects Belgium to fall to his share of the spoils, as by right it should. England's taking Belgium is therefore not too politic, and should be unaertaken only as a temporary measure.

I should add here that England's diplomacy should not seek alliances so much as friendships. Getting the other Continental powers to attack each other is a primary goal for England. Then, when they do, he can pick the side he will join at his leisure, making his choice so as to gain the best advantage out of the deal.

England's Development

England has three neighbors: France, Germany, and Russia. One of them must be attacked and destroyed (or reduced to impotence). There is some danger that all three will combine against England, but such an extensive effort to roast a bony chicken is unrealistic and self-defeating, so that even if such a threat does develop, England should be able to break it up with a little astute diplomacy.

Attacking Russia, if not dumb, is at least not very smart. England may have to do it for defensive purposes, if Russia proposes to attack him. In this instance, neutralizing Russia, perhaps by holding St. Petersburg is about as much as England should essay to do. Leaving Russia alone is more sensible, for the following reasons:

First, because Russia as an offensive threat is not formidable. He has to build F StP (north coast), which is a clear warning, and he has to move through Scandinavia to get at England, which takes him a lot of time and trouble.

Second, England cannot expect to get too much as a general rule, beyond Sweden and StP. Attacking Hussia may be a good way to outflank Germany, create a path into the supply center-rich Balkans, or forestall a Turkish march northward -- but in general, it will not benefit England overmuch in the mid-game.

Besides, England has other worries. France and Germany, especially France, are very close to the English homeland. England can keep tabs on Germany by trying to prevent him from building fleets, but France is another matter. Even when heavily engaged in the Mediterranean, France can easily switch ground; for instance, this can be done by moving a fleet into the Mid-Atlantic on a Fall turn and then building F Brest. Germany can provide an unwelcome threat to the North Sea, especially in conjunction with some other power attacking England.

War with France or Germany, in addition to being defensively sound, provides England with attractive expansion possibilities. Let me note each of these in turn.

War with France. This is usually undertaken in conjunction with Germany. England's share is normally Brest, Portugal, and Spain. possibly Marseilles. This rich knot of supply centers is easy to defend and gives England control over the vital Straits of Gibraltar. so that he need no longer fear attack from the Mediterranean.

At the same time, it opens the Mediterranean to English expansion, promising growth at the expense of Italy, Austria, and/or Turkey. This "southern strategy" is a winning combination, holding out the hope of bountiful expansion and the elimination of England's qreatest naval rival at the same time. England usually agrees not to build armies, in return for Germany's promise not build fleets -- but this is more of a sacrifice for Germany, since German-held centers at Belgium, Holland, Kiel, and Denmark are still open to an English stab. This alliance can also look forward to cutting up Russia, with some slight gain in centers and great gain in position for both.

War with Germany. This is usually undertaken in alliance with France. England builds some armies, and France has some fleets in the south -- for once Germany is eliminated, England must seek his fortune in the Continental interior and France must seek his on the Mediterranean littoral. This is an effective combination. England gains Holland Isometimes), Denmark, Kiel, and Berlin (this last may fall to Russia), and a position which now flanks Russia to the west. makes Warsaw and Moscow more accessible, and creates a situation where war with Russia will be much more profitable for England (and much more necessary). Further, England now has potential access to the rich Austria/Balkans clump of centers. Of course, France will hold Munich and be interested in that clump, too, so England is not out of the woods yet.

England will normally find that it is easy to make one of these two alliances. France and Germany do not readily work together. Their proximity, their often conflicting goals, their difficulty in cooperating against anyone but the bony fish of Engiand, and the tradition of Franco-German rivalry which history has impressed upon all of us all combine to make a French/German alliance one of the most unlikely on the board. For this reason, each will usually seek the help of England against the other.

In most instances, a victorious England will eliminate two of his three neighbors (if not all three). This is an effect of the geographic situation. An alliance with Germany will ultimately nave to strike at both France and Russia; an alliance with France pushes England against the eastern pair: an alliance with Russia pushes England against the western pair.

In dealing with the Continent. England has one very effective weapon: the convoy. Once England dominates the seas around him, he can -hustle armies landward as fast as he can build them. Fleets positioned in the North, Norwegian, Helgoland, Baltic, and/or English will do this very efficiently. Armies can enter Germany via Nth-Hel, for instance. One of the best convoy systems is the one which convoys armies to Denmark via Nth on one turn, and thence into Livonia of Prussia via Bal on the next, providing an effective shuttle into Russia -- and a short-cut to war Austria, by the way. F Nth can provide service into Scandinavia (and thence to Russia) or the Low Countries, while F Eng can provide service into the Low Countries or France.

England, following the "southern strategy", often finds a convoy chain convenient which runs: English Channel - Mid-Atlantic - West Med. - Tyrrhenian (or - Gulf of Lyons). This provides rapid transit into Italy, and England will find it most profitable to convoy armies over this route -- they break down the Italian defenses and eventually can be used against Austria or convoyed further east agianst Turkey.

England's Endgame

England can win by mounting a convoyed land assault on Central Europe or a seaborne attack on southern Europe. This could produce some unusual configurations. In postal game 1966C (which is even now still active and in the early 1920's), England has left both France and Germany to their own devices, has conquered Russia and Austria while sending some fleets south, and is now closing onto Turkey from both sea and land.

On the whole, a successful endgame for England depends on two factors. First, settlement of the western question in his own favor, each of the western powers either eliminated or allied with England. Second, an indecisive war in the east, so that no eastern power, particularly Turkey, has been able to dominate in that quarter. Diplomacy's inventor, Allan Calhamer, once referred to England and Turkey as "the Wicked Witch of the North and the Wicked Witch of the South" (EREHWON, III.8). They can be just as wicked to each other as to others.

England has need, often, of a powerful and cooperative ally. Turkey has an easier time establishing an empire on his own. For this reason, a common enough pattern is an Anglo-French or an Anglo-German alliance proceeding east and running into a powerful Turkey already at 14 or 15 units or more. The result is all too often a stalemate.

The causes of this is very often that England, in his precipitate haste to care for his own welfare, has neglected that of others. Turkey could not be so much bother if he were threatened by a powerful Russia or blocked by a powerful Italy. England ought to insure that Turkey has effective enemies. If Austria, Italy, or Russia dominates the east, England will have an easier time dealing with them in end than with Turkey.

The problem here is that England's success may trigger Turkey's too. An Anglo-German alliance, for instance, very nearly always means that Russia will be done in, and Turkey can usually profit by such a situation -- in fact, Turkey may perceive that such an alliance weakens Russia and attack his northern neighbor immediately. Similarly, an Anglo-French alliance is not too healthy for Italy, often thereby removing a valuable bulwark against Turkish expansion.

All of this is oversimplified of course, because much depends on what Austria does England should therefore be more interested in Austria's policy, hoping that it will be one of enmity with the Turks. Without effective opposition in the east, England should be able to win (but watch it -- what knives do to the backs of others, they also do to wicked witches).

Defending England

England is blessed with one of the best defensive positions on the board. This defense depends primarily on the English Channel and the North Sea, and to a lesser but still important extent on the other bodies of water surrounding the island. Once these are breached, England can do very little to save himself. England's great disadvantage is that there are no supply centers bordering those of his homeland -- he is unique in this respect -- and once he is robbed of outside holdings he often has insufficient strength to defend his homeland. For this reason, his position often appears more formidable than it really is.

The greatest danger of all is that an enemy will convoy an army onto the island. This usually spells the end of England -- That is, only very adroit diplomacy will save him.

In fact, diplomacy is England's chief defense. He must convince his neighbors to avoid building fleets. He must have an effective alliance system -- and for defensive purposes Germany, who can threaten either France or Russia (or both) is ideal. He must convince potential enemies that pickings up in Limey country are pretty poor (which they are).

Finally, if after Fall 1901 Russia builds F StP (nc), Germany builds F Kiel, and France builds F Bre, England should do two things. First, write frantic letters to everybody, promising them slices of the moon on saltine crackers. Second, learn the proper etiquette for going down with the ship.

More Diplomacy Cook Book

Back to Conflict Number 2 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com