As a great power, Austria was in 1900 a weak sister Hampered by her poor naval capacity and surrounded by other Great Powers to the north and west, Austria limped into the 20th Century living on past glories and filled with a blazing lust for territorial expansion. This situation is very largely duplicated on the Diplomacy playing board. Unlike any of the other six Great Powers, Austria has only one center, Trieste, in which she can build a fleet. Italy, Germany, and Russia lie near to Austria on the north and west, while Turkey is not far away to the southeast. Austrian policy must, at the outset, deal with these situations.

In order to do well in a game, it is necessary for Austria to prosper through the four stages of the game. Diplomacy, like chess, has four very distinct stages: opening, development, mid-game, and end- game. Since I will be using these terms very frequently, let me define them now.

Opening. This is game year 1901. This is generally devoted to swallowing up the 12 neutral supply centers and to getting into position for further action. The placement of units during this period is extremely important for the later stages. On occasion one player may attack the homeland of another, but unless this is soundly based in a sure thing, it is precipitous and ill-advised (and I have yet to see a "sure thing' in Diplomacy).

Development. From 1902 on, the Great Powers begin to spar in ernest, and alliances of some against others become more concrete. This period ends with the elimination of the first Great Power (or two), or when a single Great Power has grown to 9 or 10 units.

Mid-Game. During this portion of the game, the remaining Great Powers spar for position, possibly eliminating some of their smaller rivals, and in many cases moving units quite far from home.

End-Game. The two usual configurations are: (1) A single Great Power is heading toward victory, with some or all of the smaller powers trying to stop him; or (2) two or three Great Powers are moving toward a confrontation.

All of the above is pretty oversimplified, since many games do not conform to any easily describable pattern; however, I hope it is clear what portions of a game I'm talking about.

Austria's Opening

The Austrian home centers, plus the four neutral centers to the south [Bulgaria, Greece, Rumania, and Serbia], form a tight clump of supply centers, supporting 7 units, which in the hands of a single player form one of the most easily defended areas on the board. Austria should seek to dominate this area. This does not mean necessarily that all 7 centers should be Austrian. An alliance with Turkey would mean that Bulgaria and probably Rumania would be Turkish; an alliance with Russia would mean that Rumani would be Russian. These 7 centers are the "Balkan Knot".

However, Greece and Serbia can easily be Austrian. They can be guaranteed as follows:

note 3-letter abbreviations for spaces:

"-" means "to" or "attacks",

"A" means "army'

"F'' means "fleet".

"S"

means ''support"

Spring 1901 A Budapest-Serbia (A Bud- Ser) F Trieste-Albania (F Tri-Alb).

Fall 1901 F Alb-Greece (Gre), A Ser S Alb-Gre (this could also be written F Alb-Gre S by A Ser, which is a little more efficient)

Nothing can really be done to prevent these orders from succeeding. Unless Italy intervene. spring 1901:

- ITALY: A Venice-Tri; TURKEY A

Constantinople-Bulgaria.

Fall 1901 ITALY: A Tri- Ser; TURKEY: BuI -Gre.

Here the Italian order cuts the Austrian support and the two attacks on Greece result in a stand off. This sequence is prevented by

- Spring 1901; AUSTRIA: A Vienna-Tri.

What of that A Vienna? Its use in 1901 crucial to the Austrian player's estimation of what Italy and Russia will do. Worrying about a German order of A Munich-Bohemia is waste of time [I've never seen it happen because Germany has too much eIse to occupy his attention. The prime threats are the Russian order A Warsaw-Galicia (thus threatening Vienna and Trieste) or the sequence A Ven-Tri and A Rom-Ven (thus capturing Trieste, although change in ownership does not take place unless Italy has a unit in Trieste that Fall, and threatening Vienna, Budapest, and Serbial.

Obviously, Austria cannot counter all of these threats. If he thinks any of them is likely, he must counter the most likely. His first hope is to keep Italy and Russia from making such moves. If successful, Austria could then order A Vie to hold and be neutral. If Russia does move A War-Gal, Austria still has a 50% chance of guessing which of the two threatened centers Russia will trv for land some chance of talking Russia out of any further advance). If Italy does not vacate Venice, then A Vie- Tri holds Trieste, just in case. However, if Italy tries either of the maneuvers mentioned before, and Austria has held in Vienna, he is reasonably certain to lose Trieste.

The loss of a single supply center is not as bad as it sounds. If Austria ignores the loss and proceeds to take Greece, he will still build a unit and be in a position to drive out the invader. Much will of course depend on the invader's allies. If there is an effective alliance, Austria at the best can hope for a holding action while building up an alliance system to deal with the invaders in their respective rears. The argument that 'you will be next' or 'taking my centers will make X unassailably strong' will often garner help which might otherwise not be forthcoming. This argument works best against Turkey; it is hard to believe in the case of Italy, but easier to belieye in the case of Russia.

In the opening, if Austria has reason to suspect Russia, he can always order A Vie-Gal, if he is willing to accept the consequences. That is, if Russia did not attack him, the move may strain relationships. By the same token, if Italy seems untrustworthy, Austria may attempt to outguess by ordering A Vie- Tyr of A Vie-Tri. This is all a matter of judgement, and the judgement is easier to make after you've played the position a few times. Just remember that only in extremity should Austria surrender his normally sure occupation of Greece.

Austria's Devalopment

Development begins with the builds made for 1901 (often referred to as 'Winter 1901'). If he has not been forced to by now, he must choose whom he is going to attack. And he must then place his builds accordingly. A fleet in Trieste, for instance, is not of much use in a war against Russia.

Diplomacy is a game which is so constructed that it is virtually impossible to do well without forming alliances, especially in the early stages of play. For Austria, attempting to make headway without an alliance is a complete waste of time. Furthermore, because of Austria's manifest naval weakness, his alliances must involve dependence upon foreign naval power (and therefore choice of an ally with a powerful navy). This may in turn influence his choice of an enemy.

Austria is an eastern power. As such, his chances of success depend upon two factors: his hegemony in the east and preventing the rise of a super power in the west. In essence this means that while his military and diplomatic effort must be directed toward eastern affairs, he must also have diplomatic concern in the west.

As an example, if France/England are moving to crush Germany, Austria would be well advised to encourage Italy to move against France. The resulting stalemate (Austria Development, for Austria, means having an alliance with one of three powers: Italy, Russia, or Turkey. Because I will eventually deal with all such alliance patterns separately, I am not going into the special problems of each group.

However, some general principles should be borne in mind. An alliance with Turkey is difficult because in order to expand, Turkey must go around Austria to the north or to the south, or in both directions in a pincer. The temptation for Turkey to stab Austria is therefore very great. By the same token, the alliance with Italy is difficult because it is hard for them to cooperate offensively, and adjacent home supply centers make trust difficult. It is easier for Austria to get along with Russia, but this alliance suffers from the initial disadvantage of having to send their units south and east against Turkey, and then in the opposite direction against any other enemies.

Indeed, Turkey is Austria's greatest problem Attacking Turkey means that the momentum of Austria's campaign must build up heading in one direction and then, when Turkey is out, must shift direction (unless Austria wishes to follow up by taking on Russia). On the other hand, Austria may get more benefit from attacking Turkey and, indeed, if Austria does not do so, he will spend more sleepless nights over the possibility of Turkish treachery than over any other possible backstab.

Ultimately, it is almost a requirement for success that Austria eliminate one of her Balkan rivals (Russia or Turkey) during the development. By the time he does this, if he does, he will find the western area either still deadlocked and inviting intervention, or dominated by a superpower and demanding intervention. Austria's response to this situation is, for him, the midgame (by the way, this all assuming Austria is doing well, and has not been eliminated or reduced to minor status.

Austria's Midgame

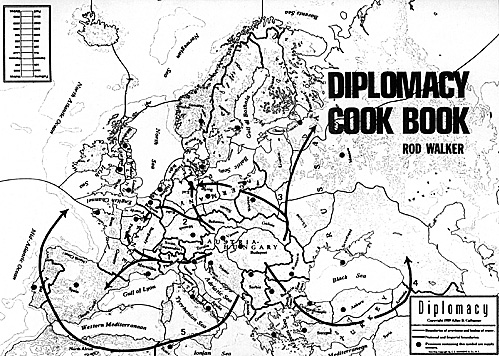

If all has gone well thus far, Austria is ready to move toward victory. There are five expansion paths open to him, as indicated on the map. Let us consider each of these.

1. Italy-France. Seizing Venice and Rome, Austria moves into Marseilles and Spain, and ultimately to Paris and Brest, thus outflanking the German position from the west. This attack is especially useful if Germany is becoming very powerful. Austna is then in a position to attack Germany across Burgundy and the Low Countries as well as across Tyrolia and Bohemia. This catches Munich in a vise and ties up the German homeland so that even if he expands he will be unable to build. This campaign is often undertaken in conjunction with no. 5.

2. Germany-France. Striking across the belt of neutral provinces to the north and west (Tyrolia, Bohemia, Galicia), Austria takes Munich and then pumps armies rapidly into Germany. Objectives include Berlin, Kiel, Holland, Belgium, and possibly Paris. This kind ot attack can be directed against an unsuspecting Germany, or against a powerful England who is not yet on the continent in force.

3. Russia-Germany. This campaign will usually come after Austria/Russia have taken Turkey out of the game. Austria then decides to stab Russia, First, Austria takes Rumania and moves (as in no 4, below) to drive Russia out of his Turkish possessions. Austrian armies move into Galicia and Ukraina. Sevastopol, Moscow, and Warsaw (and possibly St. Petersburg) are immediate objectives. By this time, the Austrian thrust has taken him near Germany, and this means that the next strike is usually for Berlin and the other German centers Once Russia falls, Germany is either temptingly weak or dangerously strong, or already ruled by some western power; in any event, Austria will want to intervene in Germany

4. Turkey-Russia. This is usually undertaken after Austria/Turkey have eliminated or weakened Russia and Austria decides to stab Turkey. The importance ot naval forces here is very great. Taking Bulgaria from Turkey is no prob. lem in many cases, but getting into Constantinople is another matter since there is only one landward approach. Allowing foreign naval power into the area is foolish (save for the Austria/ltaly 'special pair' discussed later in this series), so Austria will have to build a fleet or two (Turkey should not object, because Austria could claim them for a western cam. paign). Austria then attempts to take Turkey's home centers, in the end moving into Sevastopol.

5. Western Seas. Again, this requires naval; power. Two or three fleets may suffice against Turkey, but Austria will need at least three or four for this venture. A western naval campaign is usually undertaken in conjunction with or in support of campaign no. 1. Picking up Rome, Naples, and Tunis, Austrian naval forces push forward and sieze Spain, Portugal, and the Mid-Atlantic. The last is the most important, even though it is not a supply center. If the Mid-Atlantic and Portugal can be held by England (a fleet in each plus a single supporting fleet in one of the three bodies of water north of the mid), there is no possibility of Austria breaking through.

Austria's Endgame

Winning usually means having 18 units on the board. That, in turn, means capturing 18 supply centers. Assuming that Italy, Russia, or Turkey, one, is Austria's main ally, or he eliminates all of them, what 18 centers is he shooting for?

Austria must hold Budapest, Trieste, Vienna, Serbia, and Greece. if Austria is working with Russia, he will also receive Bulgaria and one other Turkish center, say, Smyrna. That's 7. Working with Russia means that campaigns 1 and 5 will have to be used. This adds: Venice, Rome, Naples, Tunis, Marseilles, Spain, Portugal, and Paris, 8 more for 15 Brest and Munich may be added for 17. The winning center may be picked up at Russia's expense, or may be Belgium or one of England's home centers.

Working in tandem with Italy means something quite different. Austria should pick up the entire Balkan Knot (7i, Turkey (3i, and Russia (possibly not St. Petersburg, though) (3). That's 13, from campaigns 3 and 4. Campaign 2 should yield Berlin, Kiel, Munich, Holland, and Belgium, for.~ total of 18 Note that this entire area can be gained without naval power (save entry against Turkey, which may be managed with help from Italy or by sneaking in through Armenia).

Working with Turkey makes things more difficult. Four centers named above (Bulgaria and the Turkish centers) are not available, and Turkey may have Sevastopol as well. If Turkey conducts a naval campaign, Austria must turn north, as when allied with Italy. In addition to the centers named, Austria will need St. Petersburg, Paris, and Brest, plus one or two more in order to win. The rest of them are either centers Turkey is likely to reach first, far more easily held by English sea power than captured by Austrian land power.

If, on the other hand, Turkey goes north by land, into Russia and Germany, Austria must go through Italy, as when allied with Russia. But he is two centers (Turkish home centers plus Bulgaria) short, and must add two more vvestern centers to his list.

In this case, perhaps, the other two English home centers. On the other hand, it is obvious that it is easier in this for Austria to win than Turkey, who has to go 'round Robin Hood's barn to get much of anything. This is why, especially in the late midgame, or in the endgame, when Turkey realizes the position he's in, that Austria had better jolly well guard the back door.

Defending Austria

It is said that the best defense is a good offense, but in fact, a good offense needs to be predicated upon a good defense. While all of Austria's boundaries are sensitive to one degree or another, there is one area which is supremely sensitive. The belt of provinces Tyrolia/Bohemia/Gaiicia is the best defense Austria has. There is almost no reason in the world why any power (save Austria) should maintain an army in any of these places. Anybody who enters them is probably out to get Austria.

Germany sometimes asks to enter the Tyrol in order to invade Italy; however, Austria should resist this. After all, if Italy is invaded, it is Austria vvho should benefit, not Germany. Further, if Germany does pick up Italian centers, the only way he can unify this empire is by taking the Austrian home centers (the people of the Danube and Sava valleys found this out, to their sorrow, in the 9th and 10th Centuries).

The beauty of this arrangement of provinces is the use Austria may make of it in defense. By using a system of interlocking supports, this line may be held for some time. Eventually, Bohemia, Tyrolia, and Galicia must fall in turn, but Austria has lost nothing but position. The actual supply centers are harder to take.

Even so, it must be realized that this position can be broken or out-flanked. But doing either takes time. This time can be used by Austria to apply diplomatic pressures. In postal game 1966AA, I was faced with exactly that situation. My front was beseiged by Germany, and my flank was being turned by the English navy. I had also failed to eliminate Turkey, who vacillated between hostility, neutrality, and amity. Several seasons went by, while I held the Balkan Knot and struggled for possesion of Italy. Finally, just as the fall of Vienna became certain and I had lost my toe hold in Italy, I convinced Germany that England was his chief enemy and he turned west. I went on to tie the game with Germany.

The point here is that I was able to delay serious inroads on my territory for so long that my diplomatic efforts were enabled to decide the issue. This situation is Austria's great arhantap, if properly worked.

The past paragraphs are not an exhaustive analysis of how Austria may be played. They only touch important patterns, and largely those connected with winning play. Much of what Austria may do in a given game, however, depends on the specific situation, and there are far too many variables to generalize. I have dealt with Austria in the abstract, but in Diplomacy every country has the living personality of the player to whom it has been assigned. Your decisions and actions will obviously be influenced by what you know, or think you know, about the various players. There are instances in which difficult alliances will become easy and sure- fire alliances will become impossible.

On the whole, it is best to remember that Austria cannot play a waiting game. He must move to secure the Balkan Knot and to eliminate a local rival quickly. Austria's geographic position makes it easy for him to reach a large number of supply centers quickly; however, the Balkan Knot is a tempting target for more nations than Austria, and he must therefore move decisively from the start.

Back to Conflict Number 1 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com