Minnesota had only achieved statehood in 1858, and in August 1862 it was still very much Frontier territory. Its inhabitants included some 200,000 white settlers, a third of them German, who lived in apparently relative amity with the native population of Sioux, Chippewa and Winnebago Indians. Minnesota was strongly Unionist in sentiment, and it was a common enough event when on August 18th, a waggonload of recruits for the Northern Army set off from the town of New Ulm.

Minnesota had only achieved statehood in 1858, and in August 1862 it was still very much Frontier territory. Its inhabitants included some 200,000 white settlers, a third of them German, who lived in apparently relative amity with the native population of Sioux, Chippewa and Winnebago Indians. Minnesota was strongly Unionist in sentiment, and it was a common enough event when on August 18th, a waggonload of recruits for the Northern Army set off from the town of New Ulm.

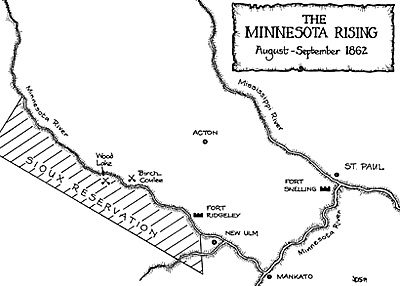

Just outside the town, they were ambushed by a party of Sioux. The survivors fled back to New Ulm, carrying the first news of what was to be one of the major Indian uprisings of Frontier history. As the citizens, militia and sheriff's men hastily erected defences, they were joined by some of the hundreds of refugees pouring either into New Ulm or beyond to the state capital of St Paul. Already some 350 men, women and children lay dead in the smoking ruins of their farmsteads.

The uprising came as a complete surprise, though the signs had been apparent for some time. The immediate trigger had been the Confederate successes of the early summer, but Indian grievances went back much further, and they saw in the Northern defeats an opportunity to avenge themselves for the loss of their lands and their exploitation by cheating Government agents. As one of the participants later remembered: "We understood that the South was getting the best of the fight, and it was said that the North would be whipped. It began to be whispered that now would be a good time to go to war with the whites and get back the lands."

The rebellion was begun by Eastern or Santee Sioux, who in 1851 had been forced to cede 24 million acres of their lands and move into a 20 by 150 mile strip of territory along the upper Minnesota River. Here they were involved in constant friction with cheating Government agents and came undr increasing pressure from the growing numbers of settlers around them.

Matters were worsened in 1858, when the Santee chiefs led by Little Crow (at right) were pressured into giving up half their reservation, and cheated of the payments which they had been promised in return. For some time Little Crow, who recognised the futility of challenging the power of the United States, held the resentful Sioux in check, but in the summer of 1862 the threatened uprising was detonated by the appointment of a new Government agent, Thomas Galbraith, who delayed promised consignments of food for the starving Indians.

Matters were worsened in 1858, when the Santee chiefs led by Little Crow (at right) were pressured into giving up half their reservation, and cheated of the payments which they had been promised in return. For some time Little Crow, who recognised the futility of challenging the power of the United States, held the resentful Sioux in check, but in the summer of 1862 the threatened uprising was detonated by the appointment of a new Government agent, Thomas Galbraith, who delayed promised consignments of food for the starving Indians.

The rising began on August 17th with a brawl at the village of Acton, during which five settlers were killed. With conflict now inevitable, Little Crow reluctantly agreed to put himself at the head of his people, though he had no illusions about the likely outcome, warning them: "You will die like rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the Hard Moon."

Soon there were several hundred Sioux in arms. On August 18th, a patrol from Fort Ridgeley, led by Captain Marsh was ambushed on the Minnesota River. Marsh and 25 of his men were killed. The Fort was left with a garrison of only 22 men, under a 19 year-old Lieutenant, Thomas P. Gere. Gere sent urgent word of his plight to Fort Snelling, and Governor Ramsey at St Paul, and prepared to fight, knowing that if Fort Ridgely fell, the Indians might sweep on to St Paul.

More The Minnesota Uprising, 1862

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 8 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com