The Shangani Patrol

Forbes command resumed its advance on 29 November. There are some discrepancies in the figures given by different sources, but Forbes' command now consisted of between 150 and 160 men. Commandant Raaff commanded the largest contingent, the BBP, while Major Allan Wilson commanded men from the Victoria Column and Captain Borrow the Salisbury Column contingent. The men carried ten days' reduced rations and 100 rounds of ammunition each; there were two Maxims, carried on pack-animals, with 2,100 rounds each. It was not much of an army, given that Forbes had no reliable figures for the strength of the Ndebele army, but it was generally believed that the Ndebele were in no position to resist a vigorous attack, and great faith was placed, in any case, on the stopping power of the Maxim.

For several days the column pushed north towards the Shangani river. A number of Ndebele prisoners were taken, most of whom declared that the king was on the banks of the Shangani with only a handful of demoralised warriors to defend him. This was encouraging, but dissension within the column continued, and a number of officers began to express doubts about Forbes' capabilities.

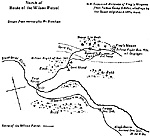

Large Tactical Map (64K)

The river was wide, but not particularly deep; the recent rains had not yet filled its watershed. The tracks of several hundred people and at least two wagons - which Lob engula was known to have with him - could be seen descending the banks towards a drift. There was a feeling of excitement in the air, that the quarry was close at hand. Forbes called Major Wilson to join him, ordered him to select twelve men, and to reconnoitre the river; he was to try to discover the king's whereabouts, but was to return before dark.

Wilson

It was a command which Wilson no doubt relished. Wilson, a Scot, was a big man with an impressive moustache and an equally impressive record of colonial warfare. He was a man of action whose character and manner had made him one of the most popular officers in the Company's army. Despite Forbes' order to return before dark, Wilson was being handed a golden opportunity to make a dash for the king. If Lobengula were still in the vicinity of the river-bank, and the Ndebele with him were as demoralised as rumour suggested, it might have been possible for a light but determined patrol to ride straight in and arrest him.

Wilson quickly rounded up the eleven men he needed, from his own Victoria Rangers, but so many were keen to join him that he stretched the point and took twenty. At the last minute a scout, an American named Frederick Burnham, joined them, so that it was a party of 21 that set out to find the king. Most of the men had expected to be back before nightfall, and several did not bother to take their jackets.

Wilson's men crossed the river without difficulty, passing one of Lobengula's wagons, which had stuck in the sand, and which heightened their excitement that the king was close at hand. The country on the opposite side of the river was covered with mopani bush, and here and there the visibility was shut in to just a few yards. The patrol rode on, however, until Burnham spotted a scherm - a temporary barricade of cut bush - ahead of them. This was final proof that the king was close by, and that a large number of people were with him.

The discovery put Wilson's resolve to the test. Already, he was stretching his interpretation of Forbes' order, which, taken literally, implied that Wilson should now return to camp, having located the king and achieved his objective. Yet the patrol had come so far, and in such difficult circumstances, that it must have been almost impossible for a man of Wilson's resolve to turn back, with victory within his grasp. Hardly pausing, he rode up to the scherm and shouted out in siNdebele that he had come in peace, and wanted to talk to the king to settle matters. He asked if any of the Ndebele would guide him to the king. The Ndebele - a mixture of warriors and women and children - seemed surprised by the encounter, but not aggressive. One man offered to accompany Wilson to the king's camp.

The guide led them about five miles further on from the river. Along the way, two horses became lame, and Wilson ordered the men to return to Forbes. There were large numbers of Ndebele moving about in the bush, but none seemed overtly hostile. At last the bush gave way to more open country, and several more scherms lay ahead. Undaunted, Wilson led the patrol straight through them. It was getting dark, and the sudden vision of white horsemen looming up out of the twilight must have caused the Ndebele some consternation, but again Wilson was not molested. At last, they came to a final scherm, surrounded by palings of mopani wood, about eight feet high. Through the branches they could see the dim outlines of two wagons; it seemed that they had found the king at last.

The events of the next few moments have an almost Shakespearean quality of drama about them. The Ndebele whom the patrol had ridden through were now recovering themselves, and began to collected behind the patrol, back down the path they had come. Many were armed, but they seemed uncertain how to proceed. Wilson ordered Captain Napier to call out to the king in siNdebele, explaining that the patrol were envoys, come to escort the king to Bulawayo to negotiate a peace treaty.

There was no reply, but overhead the gathering darkness began to rumble with thunder. Napier called out again; again no reply. It started to rain. In the lightening flashes, Wilson's men could see that the Ndebele were becoming increasingly confident, and in the silences between thunder claps they heard the ominous sound of guns being cocked. It was a moment of awful decision for Wilson; clearly, he was not going to seize the king quite as easily as he had hoped.

The patrol regrouped at the edge of the bush, and rode off to find a spot to camp for the night. From here, Wilson sent Captain Napier and two men back towards the river with a message to Forbes.

On the southern bank of the river, Forbes' command, too, was in difficulty. Captured Ndebele herd-boys revealed that the king had sent troops back along the track to prevent the white men from pursuing him. They must have missed Wilson in the bush, but sure enough when Forbes investigated, there did seem to be a large number of warriors collected in the bush on his side of the river.

Forbes must, by now, have realised that Wilson's patrol was in danger of being cut off, yet the growing darkness, bad weather, and the unknown number of Ndebele lingering nearby made it almost impossible for him to risk a dash across the river to join Wilson and try to intercept the king. The situation did not improve when Napier arrived in Forbes' camp during the night. Although he gave an accurate assessment of Wilson's position, it was clear that Wilson had given Napier no indication of what he expected of Forbes, or what he himself intended to do next.

At this point Forbes made a serious error. Clearly, he felt he could not leave Wilson to his fate, yet at the same time he was reluctant to cross the river before dawn. Instead, he compromised by sending Captain Borrow and 20 men of the Salisbury Horse to reinforce Wilson. Although he didn't know it, he was effectively signing their death warrant.

Nevertheless, the king was deeply depressed by his defeat, and by the time he neared the Shangani, he was tired and ill. After discussing the matter with his councillors, he decided to surrender, and envoys were sent to intercept Forbes' column, bearing a bag of gold coins as a peace offering. Sadly, these envoys were intercepted by a picket from Forbes' command, who took the money and kept quite; this was probably the reason why the Ndebele, who may have known of the king's peace overtures, allowed Wilson to pass through their camps unmolested.

Forbes' apparent lack of reaction to the peace offering confused the king. As the pursuing column drew nearer, it was decided to send the largest concentration of troops left in good order back across the Shangani to block Forbes' advance. Somehow this force missed Wilson in the bush, and took up a position on the south bank of the river. Borrow's men crossed the river without encountering it, but sometime after Borrow had passed the senior Ndebele commander, Mtshane Khumalo, decided to take part of this force back across the river to investigate reports that a party of white men had found the king.

Thus on the night of 3/4 December, a large force lay ahead of the Wilson/Borrow party, with the king, while another was closing in from behind, between them and the river. Another large force lay close to Forbes in the darkness. It is impossible to estimate with any certainty the size of these forces; some accounts put the total Ndebele force at as much as 7000, but this undoubtedly included women and children. The force facing Forbes may have numbered as many as 1,500 men, while the party moving between the river and Wilson several hundred. There were probably at least another thousand warriors in the camps around the king.

On their way to join Wilson, two of Borrow's men became separated from the main party in the darkness, and turned back. Borrow reached Wilson shortly after dawn. It must have been a chilling moment for Wilson's patrol, then, to realise that Forbes was not immediately to hand, for with day-break they could expect whatever fears had disheartened the Ndebele to vanish, and an overwhelming attack was, at the least, highly likely. Wilson conferred with his officers, and for reasons which cannot now be fully explained they decided not to make a dash for the river, but to make one last attempt to capture the king. Perhaps they felt that their one chance of survival lay in the king welcoming them as envoys.

The patrol set out at first light, away from the bush and towards the open country where they had found the king the night before. Wilson's total command numbered 37 men; around it lay what remained of the Ndebele nation. The patrol reached the scherm, and once again called out in siNdebele; again there was no response. This time there was no sign of life within; the king had gone. Suddenly there was a crackle of rifle-fire, and large numbers of Ndebele warriors rose up around them from the long grass and behind bushes.

A few hundred yards further on, a huge anthill lay close to the track. Here Wilson ordered the men to dismount again. While he climbed to the top to direct events, the men sheltered their horses behind it, and took up a firing line facing the warriors. They poured a heavy and accurate fire into the Ndebele, who scattered towards the bush on either flank. From here they began shooting back, a wild, inaccurate fire, but the sheer volume of it had soon wounded several more men and horses.

Clearly, Wilson could not hold the position indefinitely and he ordered the patrol to retreat once more. Where there were not enough horses, wounded men had to be taken up behind able ones.

From the anthill the patrol rode in good order across a patch of marshy ground towards the bush line where they had sheltered the night before. A few knots of warriors rushed forward to cut them off, but where shot down by the rear-guard.

Once he reached the bush, Wilson told the scout, Burnham, to try to break through to Forbes, and to urge him to cross the river to join them. Burnham took two men with him; they were the last white men to see Wilson alive. After a terrifying ride through the forest - a story which grew in Burnham's telling - they succeeded in crossing the Shangani, swollen by the rain of the night before, only to find that Forbes' command was pinned down under Ndebele attack.

The Wilson party was now just 34 men strong. They continued to retreat through the forest, but it must soon have become clear that the Ndebele had cut them off from the river. In a small clearing they came across another anthill, and here Wilson decided to make a stand. The men dismounted, apparently arranging their horses in a circle, and standing behind them as cover. Visibility was quite good, for most of the bush consisted of mopani trees, which grew straight up for about ten feet off the ground before branching out. The ground between the trees was littered with fallen branches. Here and there were patches of long grass and shrubbery.

Much of the story of the patrol's last hours comes from Ndebele sources.

Many of the patrol were repeatedly wounded, but kept on firing or handing out ammunition until their strength failed them. According to some accounts, the patrol sang songs from time to time, to keep up their spirits, and from this has grown the legend that Wilson's men were singing "God Save the Queen" when death overtook them.

On the south bank, Forbes' patrol was attacked early that same morning. An Ndebele rush was driven back with Maxim fire, but for more than an hour the warriors shot at them from the bush. The arrival of Burnham, and the sound of distant firing across the river, made Wilson's fate all too clear. Forbes' own column now numbered at the most 120 men, while the Shangani river was steadily rising.

He had little option but to retreat. Forbes' column began to retire back down the Shangani, towards Bulawayo, and the Ndebele harried them for much of the way. Morale in the column was on the point of collapse; despair over the fate of Wilson affected the whole command, while the officers bickered bitterly among themselves. It was not until 14 December that the column was afforded any hope of relief, when scouts sent out from Bulawayo located it and brought in in in safety.

The story of the Shangani patrol was one of unmitigated disaster. Wilson's party was slaughtered, King Lobengula escaped, and Forbes was driven back in disarray. Although many officers blamed Forbes for the fiasco, the responsibility really lay with Jameson, who had sent the men out so lightly and without any real sense of the condition of the enemy they were facing. Within a few weeks, fate conspired to bring down the final curtain on the whole sorry drama.

Lobengula and his entourage reached the Zambesi valley, but the king's health was broken, and he died a few days later, possibly from the effects of exhaustion exacerbated by malaria. Commandant Raaff, who had also been ill throughout the last campaign, died shortly after his return to Bulawayo.

All Ndebele resistance ended with the death of the king, and the Company parcelled out Matabeleland to its prospectors and farmers. Yet many Ndebele, once the shock of defeat had worn off, refused to accept the white army of occupation. Three years later, most of the Ndebele, and many of the Shona, rose in revolt against the Company's rule.

At present, there is no one book which does for the Ndebele kingdom what Donald Morris'

The Washing of the Spears and John Laband's Rope of Sand have done for the Zulu, or Noel Mostert's Frontiers has done for the Xhosa. The definitive book on the Shangani Patrol remains Robert Carey's A Time To Die (Cape Town, 1969). John O'Reilly's Pursuit of the King (Bulawayo, 1970) is essentially a discussion of the various intricacies of the story, and is best read with Carey. The Warriors, by R. Summers and C.W. Pagden (Cape Town, 1970) is an important study of the Ndebele army, including costume and weapons, although it's portrayal of the army's role in civilian society is unconvincing. The academic studies of Julian Cobbing give a more viable picture of how Ndebele society worked. Oliver Ransford's

Bulawayo: Historical Battleground of Rhodesia (Cape Town, 1968) is essentially a book about the city, but it give a good account of Lobengula's capital. It's account of the Matabele War is surprisingly thin, but it gives a very accessible description of the Rebellion of 1896. The story of the Shangani Patrol was made into a film by the same name in South Africa, although all attempts to locate a copy have so far failed; the incident was portrayed briefly, and not very accurately, in the BBC series, Rhodes.

Section One: Last Stand of the Shangani Patrol

Late on the afternoon of the 3rd, the Column reached the banks of the Shangani river.

Late on the afternoon of the 3rd, the Column reached the banks of the Shangani river.

Jumbo Tactical Map (112K)

Across the Shangani

As the rain came down in a sudden torrent, Wilson shouted for his men to scatter and make for a clump of bush back down the track. The rain seemed to have dampened the resolve of the warriors, and the patrol rode away without interference. An electric moment had passed, but the fact remained that Wilson's patrol was now in a very difficult predicament, several miles from the river, in the dark and rain, with an unknown number of Ndebele cutting off its line of retreat.

As the rain came down in a sudden torrent, Wilson shouted for his men to scatter and make for a clump of bush back down the track. The rain seemed to have dampened the resolve of the warriors, and the patrol rode away without interference. An electric moment had passed, but the fact remained that Wilson's patrol was now in a very difficult predicament, several miles from the river, in the dark and rain, with an unknown number of Ndebele cutting off its line of retreat.

On the Shangani

Ndebele Movements

Although, as most Company officials, including Jameson, had guessed, the Ndebele army had indeed been greatly demoralised by its defeats during the invasion, it was by no means a spent force. Lobengula had left Bulawayo shortly before Jameson had occupied it, moving slowly northwards, towards the Zambesi valley. He had with him the remnants of the forces who had fought at Shangani and Bembesi. Some amabutho, who had suffered badly in the battles, were largely broken, but others maintained something of their discipline and order. They were joined in their flight by the regiments under Gambo Sithole, who had unsuccessfully attacked the southern column. In addition to the warriors, many hundreds of Ndebele civilians accompanied the king in retreat.

Although, as most Company officials, including Jameson, had guessed, the Ndebele army had indeed been greatly demoralised by its defeats during the invasion, it was by no means a spent force. Lobengula had left Bulawayo shortly before Jameson had occupied it, moving slowly northwards, towards the Zambesi valley. He had with him the remnants of the forces who had fought at Shangani and Bembesi. Some amabutho, who had suffered badly in the battles, were largely broken, but others maintained something of their discipline and order. They were joined in their flight by the regiments under Gambo Sithole, who had unsuccessfully attacked the southern column. In addition to the warriors, many hundreds of Ndebele civilians accompanied the king in retreat.

To Brave Men

Wilson ordered the men to dismount and take what cover they could, and return the fire. The Ndebele hung back, but one of Wilson's men was wounded and two horses killed. Wilson ordered the men to remount, to take advantage of the temporary Ndebele repulse, and to retreat. They rode back through the undulating country towards the bush. By this time, the Ndebele numbers had swollen to several hundred, and they followed closely behind, encouraged by the patrol's retreat.

Wilson ordered the men to dismount and take what cover they could, and return the fire. The Ndebele hung back, but one of Wilson's men was wounded and two horses killed. Wilson ordered the men to remount, to take advantage of the temporary Ndebele repulse, and to retreat. They rode back through the undulating country towards the bush. By this time, the Ndebele numbers had swollen to several hundred, and they followed closely behind, encouraged by the patrol's retreat.

Initially, the warriors made a fierce rush, but they were driven back to cover by the fire of Wilson's men. From here they began to return the fire, and the patrol's horses fell one by one, until at last the survivors were all lying behind a circle of dead animals. Some of those in Wilson's party who could speak siNdebele apparently called out, challenging the warriors to fight hand-to-hand. "No," came the reply, "we have got you today!" Nevertheless, several times individual Ndebele izinduna did try to mount a rush on one side of the circle or another, but each was driven back.

Initially, the warriors made a fierce rush, but they were driven back to cover by the fire of Wilson's men. From here they began to return the fire, and the patrol's horses fell one by one, until at last the survivors were all lying behind a circle of dead animals. Some of those in Wilson's party who could speak siNdebele apparently called out, challenging the warriors to fight hand-to-hand. "No," came the reply, "we have got you today!" Nevertheless, several times individual Ndebele izinduna did try to mount a rush on one side of the circle or another, but each was driven back.

Perhaps some did sing, but whether the songs were patriotic, religious or bawdy cannot now be identified; the sound may equally have been the cheering with which the soldiers greeted each Ndebele repulse. For perhaps two or three hours, Wilson's men kept the Ndebele at bay, until there were too few of them to resist any longer. A final rush from the bushes over-ran them, and the survivors were speared to death.

Perhaps some did sing, but whether the songs were patriotic, religious or bawdy cannot now be identified; the sound may equally have been the cheering with which the soldiers greeted each Ndebele repulse. For perhaps two or three hours, Wilson's men kept the Ndebele at bay, until there were too few of them to resist any longer. A final rush from the bushes over-ran them, and the survivors were speared to death.

Forbes' Retreat

Aftermath

In early February, a trader named Dawson, who was well known to the Ndebele, volunteered to look for the remains of Wilson's patrol. He found the skeletons of men and horses much as they had fallen. His Ndebele informants assured him that they were much impressed by the patrol's courage; they were, declared the Ndebele, "men of men, and their fathers were men before them". Dawson interred the bones in the shade of a tree, on which he carved the legend "To Brave Men". Six months later, at Rhodes' request, the remains were exhumed and reinterred beneath a huge memorial on top of the Matapos hills.

In early February, a trader named Dawson, who was well known to the Ndebele, volunteered to look for the remains of Wilson's patrol. He found the skeletons of men and horses much as they had fallen. His Ndebele informants assured him that they were much impressed by the patrol's courage; they were, declared the Ndebele, "men of men, and their fathers were men before them". Dawson interred the bones in the shade of a tree, on which he carved the legend "To Brave Men". Six months later, at Rhodes' request, the remains were exhumed and reinterred beneath a huge memorial on top of the Matapos hills.

Further Reading

Back to Age of Empires Issue 13 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Empires/ Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com