The story of the Ndebele (or Matabele; they are different versions of the same word) kingdom has not captured the public imagination in quite the same way as that of the Zulu kingdom. There are, perhaps, good reasons for this; although both kingdoms were broken up by the British, the Anglo-Zulu War saw extensive use of regular British red-coats, with a suitably dramatic mixture of terrible disasters and heroic victories, while the Matabele were broken up largely by Cecil Rhodes' private army, the rather less-glamorous forces of the British South Africa Company. Nonetheless, it is a shame that Ndebele history has not received more attention; as the recent TV series Rhodes suggested, it, too, has its fair share of drama and blood-shed.

The story of the Ndebele (or Matabele; they are different versions of the same word) kingdom has not captured the public imagination in quite the same way as that of the Zulu kingdom. There are, perhaps, good reasons for this; although both kingdoms were broken up by the British, the Anglo-Zulu War saw extensive use of regular British red-coats, with a suitably dramatic mixture of terrible disasters and heroic victories, while the Matabele were broken up largely by Cecil Rhodes' private army, the rather less-glamorous forces of the British South Africa Company. Nonetheless, it is a shame that Ndebele history has not received more attention; as the recent TV series Rhodes suggested, it, too, has its fair share of drama and blood-shed.

In particular, one incident in the Matabele War of 1893 stands out as bearing comparison with Custer's defeat at Little Big Horn, or even Isandlwana, albeit on a much smaller scale. The last stand of Major Allan Wilson's patrol on the banks of the Shangani river became one of the epic incidents in the founding of 'Rhodesia', although the story is only remembered by a handful of enthusiasts today.

The Ndebele people had a long and eventful history before their fateful encounter with Cecil John Rhodes. The original core of the kingdom was of Zulu stock; in the early 1820s, a chief of a section of the Khumalo people, Mzilikazi ka Mashobane, who lived in northern Zululand, broke away from the overlordship of King Shaka Zulu. With a few hundred followers, Mzilikazi crossed the Kahlamba ('Drakensberg') mountains into the interior. He settled for a while in the eastern part of modern Mpumalanga province before re-establishing himself in the Magaliesberg hills, around modern Pretoria.

Here he built up a new following, modelled initially on the Zulu prototype, but incorporating many of the Pedi and Sotho peoples from the interior, whom he had conquered. Here he remained until 1836/7, when he clashed with Boers moving northwards during the Great Trek. He was driven out of his settlements around the Magaliesberg, and the entire nation moved north, across the Limpopo river. Here, in what is now south-western Zimbabwe, he reconstituted the kingdom once more, building a new capital at Bulawayo, north of the Matopos hills. Mzilikazi lived out the rest of his life in comparative freedom from European influence, and died in 1868. He was succeeded by his son Lobengula kaMzilikazi.

The Ndebele Army

The Ndebele kingdom was essentially a reflection of the Zulu state, modified and adapted according to the different circumstances and peoples the Ndebele encountered in their journeys. Like the Zulu, the Ndebele king ruled over a conglomerate of local chiefdoms; these consisted of a core of original Zulu speakers, later augmented with Pedi, Sotho and Tswana speakers, who, in the kingdom's final incarnation, were overlaid over the pre-existing Mashona chiefdoms of Zimbabwe. Some Shona chiefdoms were driven out so that the Ndebele could establish themselves, while others continued to exist while acknowledging Ndebele authority.

To bind this diverse kingdom together, Mzilikazi had raised age-set regiments - amabutho - from among his followers. In the kingdom's early days, these seem to have closely resembled the Zulu model, with each regiment being allocated a specific headquarters complex, which were scattered strategically about the kingdom. By the 1890s, however, the incorporation of so many non-Zulu elements had begun to affect the way the amabutho were raised. The king continued to form regiments from young men of military age from across the country on a regular basis, and they were appointed specific districts within the country to occupy. They no longer built amakhanda - military barracks - however, but instead erected a number of ordinary homesteads.

Many of their family would later join them, and in due course, when the king allowed the men to marry, the warriors would bring their wives to join them. Thus the process of raising regiments was part of a continuing process of internal colonisation and settlement. Most Ndebele regiments were of mixed racial stock, although some attempt was made to keep the best regiments composed of men of Zulu blood. Unlike in the Zulu system, where younger men were enrolled in fresh regiments in due course, the local flavour of some of the Ndebele amabutho meant that subsequent generations were enrolled in their father's regiments, to keep up the numbers.

Of course, the Ndebele warrior was no more a full-time soldier than his Zulu counterpart; he was a citizen-soldier who spent most of his time living at home and raising his cattle, and only fought as a warrior when the king called out his regiment.

Uniform

In Mzilikazi's time, Ndebele regiments dressed much as they had in Zululand. They carried large cow-hide shields, and their principle weapon was the stabbing spear. Over the years their appearance changed somewhat, however, as the original Khumalo core was diluted, and they relocated in parts of the countryside where different natural resources were available to them. There is a good deal of evidence that in 1893 Ndebele regiments were still distinguished by the colours of their shields, and that this may still have followed the broad Zulu pattern of black shields for younger regiments and white for senior ones.

In Mzilikazi's time, Ndebele regiments dressed much as they had in Zululand. They carried large cow-hide shields, and their principle weapon was the stabbing spear. Over the years their appearance changed somewhat, however, as the original Khumalo core was diluted, and they relocated in parts of the countryside where different natural resources were available to them. There is a good deal of evidence that in 1893 Ndebele regiments were still distinguished by the colours of their shields, and that this may still have followed the broad Zulu pattern of black shields for younger regiments and white for senior ones.

However, more specific details regarding the particular patterns of individual regiments have not survived, and generally Ndebele shields seem to have been slightly smaller and less well-made than their Zulu counterparts. Stabbing spears remained the main weapon, augmented by throwing spears, axes, knobkerries and, to a degree, firearms. By the 1890s, most warriors in full dress wore an ornate costume consisting of a black shoulder-cape of ostrich feathers, with a headress - a circle of feathers around the head, and a large mop over the forehead - of the same. Regimental differences were suggested by additional plumes added to this framework.

Warriors of Zulu blood wore similar loin coverings to the Zulu, but those of Tswana or Shona origin wore waist-hides which passed between their legs and were knotted at the hips. In battle, most Ndebele, like the Zulu, did not wear their full regalia, although many seem to have retained the mop of feathers over the forehead.

Matabele War of 1893

The Matabele War of 1893 came about because Cecil Rhodes hoped that the country north of the Limpopo river would prove to be rich in gold and diamond deposits. Rhodes had made his personal fortune in the diamond fields at Kimberley, and he was inspired by a vision of linking south Africa to north Africa by a corridor of British possessions. He was further stimulated by the discovery of gold in the Transvaal, and schemed to both isolate the Boer republic, and to neutralise its financial advantage by making similar discoveries elsewhere.

Throughout the 1880s, Lobengula was pestered by white concession-hunters who sought his permission to prospect in his territory, and Rhodes added his own agents to the noisy crowd camped outside the main entrance to Bulawayo. Rhodes could pull more strings than most, and offer greater incentives, and he persuaded Lobengula to allow the B.S.A.Co. to occupy Mashonaland, the eastern part of Zimbabwe, over which Lobengula claimed overlordship.

In 1890, Rhodes' 'Pioneer Column' marched through Ndebele territory and established settlements at Fort Victoria and Fort Salisbury in Mashonaland. To the Pioneers' intense disappointment, however, Mashonaland failed to contain the mineral riches they had expected. Rhodes began to scheme to extend his influence into Matabeleland proper.

On the other side, Lobengula found it difficult to restrain his regiments, who resented white interference in their traditional raiding grounds. In July 1893 an impi sent to punish an Mashona chief near Fort Victoria clashed with Company troops, and a full-scale war broke out.

The Company's Army

The invasion of Matabeleland was accomplished by two columns of Company troops, and a third consisting largely of British Imperial troops, chiefly the Bechuanaland Border Police. The latter advanced on Bulawayo from the south, starting in Bechuanaland, which was a British possession, but most of the fighting fell to the Company's troops, who were determined to beat the Imperial forces to Bulawayo. The Company forces consisted of over 600 men, under the over-all command of Rhodes' lieutenant, Dr Leandar Starr Jameson.

One column started from Fort Victoria, and the other from Fort Salisbury; they advanced to a rendezvous inside Matabeleland, and thereafter advanced together, although maintaining separate administrative identities. They were volunteers rather than professionals, although there were a number of regular army officers appointed to commands among them, and several experienced colonial campaigners were in the ranks.

Each man was issue with a light khaki jacket and trousers, blue puttees and a short blue cavalry cape, though most preferred to fight in their shirt-sleeves, and only a few wore the puttees. Slouch hats were universal, often with coloured puggrees; the Bechuanaland Border Police, with the Imperial column, wore 'guinea-fowl' puggrees of pale blue cloth with white polka-dots, while some informal units wore white or red puggrees. The men were also issued with Martini-Henry rifles and bandoliers, while each column included both artillery and machine guns - chiefly Gardners and Maxims.

Each man was issue with a light khaki jacket and trousers, blue puttees and a short blue cavalry cape, though most preferred to fight in their shirt-sleeves, and only a few wore the puttees. Slouch hats were universal, often with coloured puggrees; the Bechuanaland Border Police, with the Imperial column, wore 'guinea-fowl' puggrees of pale blue cloth with white polka-dots, while some informal units wore white or red puggrees. The men were also issued with Martini-Henry rifles and bandoliers, while each column included both artillery and machine guns - chiefly Gardners and Maxims.

The Matabele War

Jameson's columns set out at the end of the first week of October 1893, and met up a week later. On 25 October the Ndebele made their first attempt to stop them, in a dawn attack on their laager (see photo at right) at the Shangani river. They were driven off by heavy machine-gun and artillery fire.

Jameson's columns set out at the end of the first week of October 1893, and met up a week later. On 25 October the Ndebele made their first attempt to stop them, in a dawn attack on their laager (see photo at right) at the Shangani river. They were driven off by heavy machine-gun and artillery fire.

On 1 November, a rather more serious attack was made at the Bembesi river (see photo at right), during which Lobengula's guard regiments, the Imbeso and Ingubu, made a heroic charge which was scythed down by machine-gun fire. The Company advance continued, and on 4 November Bulawayo was occupied. The king had already fled, and much of the royal complex had already been destroyed by fire. A few days later the southern column arrived, having fought off a Matabele attack at Empandline on the 2nd.

On 1 November, a rather more serious attack was made at the Bembesi river (see photo at right), during which Lobengula's guard regiments, the Imbeso and Ingubu, made a heroic charge which was scythed down by machine-gun fire. The Company advance continued, and on 4 November Bulawayo was occupied. The king had already fled, and much of the royal complex had already been destroyed by fire. A few days later the southern column arrived, having fought off a Matabele attack at Empandline on the 2nd.

The occupation of Bulawayo seemed to Jameson to spell the end of the Matabele War. The myth of the ferocious Matabele regiments had been broken with almost alarming ease; the king was a fugitive, and Bulawayo captured. Rhodes himself sent messages instructing Jameson to lay out a new town, the capital of the Company's new administration, on the very ruins of Lobengula's palace. It seemed that all remained was to capture the king himself to put the cap on the whole exercise. Given the extent to which the Ndebele appeared to have been demoralised by the rapid Company advance, no one expected this to be a major problem.

The Pursuit of the King

No sooner had the southern column arrived in Bulawayo than a force was organised to set out after the king. Lobengula was rumoured to be about twenty miles north of Bulawayo, with the remnants of his army. A force of over 500 hundred men, drawn from all three columns, and under the command of Major Patrick Forbes, was sent after him.

From the beginning, however, the enterprise was seriously flawed. For one thing, the men seem to have had only the vaguest idea of their objectives, and marched north-east rather than north, taking with them only a few days' rations. Forbes' second-in-command was Commandant Pieter Raaff, who had been attached to the Bechuanaland Border Police, an experienced frontier fighter who had played a conspicuous part in the Anglo-Zulu War. Raaff, however, was ill, and his heart was not in the expedition, while Forbes found it difficult to have a much more experienced officer under his command.

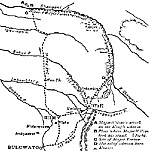

Large Map of Pursuit (slow: 87K)

For several miserable days the column blundered about, looking for the king in the wrong direction, and with officers and men alike grumbling amongst themselves. Finally, Forbes shifted his advance to the north, and occupied a deserted mission station called Shiloh. Here he decided to drastically reduce his command, sending almost half his men back to Bulawayo.

He then struck out north, following reports of the king's retreat, only too find that his command was still too cumbersome. He decided to send his supply wagons back to Bulawayo under escort, taking with him only that equipment and those supplies that he could carry on pack horses or mules.

Section Two: Last Stand of the Shangani Patrol

To make matters worse, the weather, which had hitherto been dry, suddenly broke with the onset of the rainy season.

To make matters worse, the weather, which had hitherto been dry, suddenly broke with the onset of the rainy season.

Back to Age of Empires Issue 13 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Empires/ Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com