INTRODUCTION

5 companies of the 80th Regt under Major Tucker were stationed at Luneburg, part of No.5 Column based on the Transvaal border area, keeping watch over the Boers on the Transvaal as much as the Zulus.

Supplies to Luneburg were brought up from Derby, and a convoy of around 20 waggons had set off escorted by a company of the 80th sent by Major Tucker. This company was called back to Luneburg by the Major en route on the evening of the 5th, leaving the convoy strung out over many miles and totally defenceless. It was replaced by Captain Moriarty's company sent out on the 7th.

FORCES ENGAGED

British

British Commander: Capt. D.B. Moriarty

Lt. H.H. Harward

Senior N.C.O.: Colour Sgt.

Booth

Civil Surgeon Cobbin

106 officers and men

Approximately 50 civilian

conductors and native voorloopers

Zulu

Zulu Induna: Umbelini 800-4000 estimates, smaller figure more likely.

Majority non-

Zulus, Swazi irregulars

Umbelini's stronghold only 5 miles away in hills.

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT

For a detailed full account of the action we have Major Tucker's letter written to his father on the 19th. Although not involved in the fighting, he is a reliable source as he gathered statements from the survivors for his report. Colour Sgt Booth and Private Henry Jones writing on the 13th, one day later.

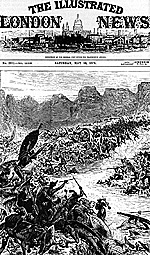

The front cover of the Illustrated London Times gives a lifelike bloody

representation of the action from an understandably condensed viewpoint. An

officer, presumably Capt. Moriarty, holds his sword aloft to spear the warrior

leaping from the waggon, whilst Lt. Harwood and Sgt Booth's detachment across

the river fire in the mass. (Picture courtesy of ILT).

The front cover of the Illustrated London Times gives a lifelike bloody

representation of the action from an understandably condensed viewpoint. An

officer, presumably Capt. Moriarty, holds his sword aloft to spear the warrior

leaping from the waggon, whilst Lt. Harwood and Sgt Booth's detachment across

the river fire in the mass. (Picture courtesy of ILT).

MAJOR TUCKER

Printed in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 1943.

Long before this reaches you, by telegram you will have heard that some of the 80th have been cut to pieces not far from here, and doubtless you will be anxious to hear all about it from me. Some waggons were coming from Derby to this place loaded with ammunition, flour, and Indian com (mealies they are called here). There was an escort with the waggons.

On the 5th, when they were, owing to the troubled state of the roads and rivers, broken down at various intervals some eight or nine miles from here, fearing an attack here that night from Umbeleni, I sent out to the escort to say they were to be in here that night at any cost. This order they carried out to the very letter, for at ten o'clock Anderson and his escort turned up, leaving the waggons as I tell you anywhere. They certainiy had passed a fearful day, having been wet thro' ever since eleven a.m., and during the whole day they were pulling waggons out of mud holes and thro' rivers.

They managed to get six waggons as far as the Intombi River, but trying to get one thro' the drift it stuck fast, and then broke, so those behind couldn't come on. Six waggons they left stuck fast three miles farther on at the Little Intombi River; these were in a very nasty place, high hills occupied by the enemy on either side, and they contained, so Anderson told me, ammunition. I could do nothing that night, but the following day I sent a party of men to the Intombi River, about six miles from here, to try and get these waggons with ammunition into Luneberg.

On arriving at the river they found it impassable, but they managed to unload the waggon stuck in the drift, and to pull it out. At night they resumed to camp. The rain had been fearful all that day. The next morning, the 7th, I sent off Captain Moriarty with a hundred men and a waggon loaded with beams and barrels to make a raft, and ordered him to get the ammunition waggons out of their difficulties and bring them on to the other bank of the Intombi and laager them with the waggons already there and to wait there until the river went down. I went out there myself that day and saw the raft constructed, but it was bad.

I started some oxen and men to get out the waggons at the Little Intombi River. Seeing the rain was coming, I rode home, but before starting I ordered the men to pitch three tents on this side of the Intombi to put their things in if the rain came on. When about half-way home rain came down in torrents--harder, if possible, than we had had before--and although I had a waterproof I hadn't a dry stitch upon me when I reached Luneberg.

On the 8th we had a very wet day and still worse night. On the 9th the rain continued. On the 10th it was fine for an hour or two, but at ten a.m. on it came again and continued until daybreak. I cannot describe to you the fearful misery the poor men were in.

Everything belonging to them had been wet thro' for days, and the difficulties they experienced in getting their food cooked in the open air was almost insurmountable. With day we hailed the morning of the 11th March fine, and later on, the sun coming out, we very soon had all our wet things dry, and our clothes once more washed, but the ground around the tents was still a sea of mud.

After lunch I went out to the Intombi Rher to see what poor Moriarty had done, and found that they had been in a worse plight than ourselves, as the river had risen so very high as to come half-way up his laager, but during the moming it had gone down considerably. You will see by the enclosed rough sketch that the men were divided, thirty-five being on this bank and seventy with the waggon laager on the opposite side.

On this side the bank all along is very steep and high, but on the other where the laager was the ground slopes gradually to the edge of the water.

When I reached them on the 11th the river was still very high and the stream rapid. I went across on the raft and it was as much as I could do to keep my feet dry; the other three officers with me all got wet. I didn't at all like the construction of the laager, first because the base did not quite rest upon the river, and secondly the desselbooms (poles) of the waggons were not run under one another or outside the waggon in front of it, as I always have laagered my waggons, but the desselbooms were tied to the back of the waggon in front, and up against the desselbooms were placed bags of mealies, thus leaving a low gap about two to three feet high between the waggons. I cannot consider this any protection whatever in the event of the Zulus attacking in numbers, as they are sure to do; they can very easily pull themselves over this.

They had all the cattle, about 250, inside the laager at night, and you will see the spot where two waggons of ammunition containing 90,000 rounds were placed. In such a position that, the attack once commenced, no one could possibly get to them on account of the quantity of cattle; but there is every excuse for the laager not being properly constructed.

He was short of oxen, and in the fearful weather he had experienced it was almost impossible for the men to have placed them properly, and when they made the laager the water was up to its base, which under ordinary circumstances would have been a very good defence. I also thought the men being divided was wrong, but this turned out to be the salvation of fortyfour lives; but for their being there not one single soul could possibly have escaped, for all those who got away from the far side had to throw away their arms in the river.

Harward was the subaltern with Moriarty, and the afternoon I was there, hearing some cattle had strayed, I ordered some men to go out and see if they could find them. It appears they went away into the hills, killed a couple of Kaffirs, took some rifles and a few goats. Coming back to camp late, Harward was very tired and, his Blankets being in Moriarty's tent, he lay down to sleep; when the latter said to him, 'You must get over to the other side to sleep,' Harward remonstrated, but Moriarty said, 'You must go; it's the Major's orders.' Now I have no recollection of having ever alluded to the matter, but that makes no difference; Harward went, and to this he owes his life.

On the morning of the 12th about six thirty a m. I was awoke by a fearful voice saying 'Major! Major!' I was up in an instant, and there, at my tent door on his knees, the picture of death, was Harward. He gasped out, 'The camp is in the hands of the enemy; they are all slaughtered, and I have galloped in for my life.'

He then fell on to my bed in a faint. I gave him some water, got him round, and he then told me as follows. All the men's statements are pretty much the same. About half past three in the moming of the 12th--it was then raining and misty--a shot was fired not far from the camp. [Close to 44.30 a.m.]. The alarm was given and the men turned out; but Moriarty, thinking it was nothing, told the men to tum in again, but cautioned the sentries to be on the alert.

There is some confusion as to what orders were given by Moriarty. Harward ordered his platoon to stand too upon hearing this shot, asking the sentry to should across to the sentry on the Captain's side for orders. He states the Captain ordered him to remain under arms. Sgt. Booth confirms this but states that they could return to their tents.

What happened on Moriarty's side of the river is less clear. Reports state that he failed to give any orders for his men to fall in. He did give the order but it was not carried out, but as the Major states he further ordered the men to fall out and for the sentries to alert. As you will read later Pvt. Jones makes no mention of falling in so it seems that no order to fall in reached the men. On his side he had two sentries right and left of his tent, about fifteen to twenty yards off. There was a small rise in front of them, so that they couldn't see fifty yards. On this side there was but one sentry, but if the morning had been clear he would have had a very good view right over the laager below him.

About five o'clock the mist began to clear and the sentry from this side saw the Kaffirs quite close to the camp and almost round it; he at once fired his rifle and gave the alarm. The sentries on the other side did the same. Of course, the men were up in a moment, some men sleeping under the waggons and some in the tents; but before the men were in their positions, the Zulus had fired a volley, thrown down their guns--these were taken up by the reserve, a very large body, they tell me, well in rear of the advance party--and were around the waggons and on the top of them, and even inside with the cattle, almost instantly.

So quickly did they come, there was really no defence on the part of our men, it was simply each man fighting for his life, and in a very few minutes all was over, our men being simply slaughtered. The cattle were all driven out of the iaager in a few seconds, and our men from this side fired volley after volley into the mass of Zulus and white men; but seeing about 200 of the enemy were crossing the river in a body rather high up, evidently with a view to get behind them, and the fighting being virtually over, these men very wisely retired; and not at all too soon, as the Zulus were coming from a hill in their rear to prevent their going into Luneberg.

Most of these men kept together, pursued by the Zulus for at least three and a half miles. When they showed symptoms of closing, the men under a Sergeant [Booth] halted and gave them a volley, which frightened the Zulus. Four men left this retreating party and took a short cut under a hill; they were met by some Zulus and all killed.

The moment Harward saw the Zulus coming across the river he saddled up the horse of another man and galloped into the camp. Only twelve men out of seventy from the far side escaped alive. One man who couldn't swim was well out in the river; a Zulu passed him without an assegai; he caught hold of the enemy, who swam with him to the opposite bank.

Another man and a Zulu were trying to drown one another when up came one of our men with his rifle and hit the Zulu with his butt. At this moment a man from this bank fired and killed the Zulu and our two men escaped. The sight in the river, they tell me, was frightful--Zulus and white men all mixed up together, yelling, howling and screeching.

I had all the horses I could raise at once saddled and, ordering 150 men to follow, started for the Intombi. About a mile from the scene we were on high ground and could see from there and from miles away to our right dense masses of Zulus extending for at least two miles under the hills, and the last Zulus were then leaving the laager for the hills eastward. They were all trotting off as fast as they could, evidently expecting we should soon be there from Luneberg.

As we approached the Intombi Drift a fearful and horrible sight presented itself, and the stillness of the spot was awful; there were our men Iying all about the place, some naked and some only half dad. On the opposite side of the drift I need not attempt to describe to you what I saw; all the bodies were full of assegai wounds and nearly all were disembowelled. This is the custom of the Zulus, arising from a superstition that unless they do so their own stomach will swell and burst.

I saw but one body that I could call unmutilated. As soon as we got to the Intombi, I shouted at the top of my voice so that any man wounded might know we were at hand. Instantly out of the earth came one of our men and two Kaffirs; our man was some considerable way down stream.

I went to him and found he was slightly wounded in the head from an assegai, and his hand cut between thumb and finger. The story is as follows. He was sleeping in a tent when he heard a shot and the sentry shout, 'Guard, tum out!' He had his arms by him and his accoutrements on him, and being at the tent door he was first out.

The Zulus were then in the act of getting on to the waggons, and a second later they were inside the laager and began to drive out the cattle; they are most extraordinary hands at handling cattle. He does not know how he got thro' the laager to the river, but being there, and not able to swim, he thought he might as well drown as be killed by the Zulus, so into the water he went and fired several rounds from there; but going in still farther, the water at last reached his neck and the stream took him off his legs.

He threw away his rifle and down the river he went; presently his foot touched the ground, but being under water and thinking he was being drowned, he undid his waist-belt and up he came to the surface close to the opposite bank. He laid hold of some grass, but it gave way with him and on he went. A second time the grass was near him and he held it, finally getting to the top of the bank; but being exhausted, having swallowed a lot of water, he rested on his hands and knees.

While in this position a Zulu came at him with an assegai; our man caught hold of his assegai and they struggled. The stick broke, leaving the blade in our man's hand, who at once killed the Zulu. The effort was too much for him; he fell back into the river, but again caught the grass, and, hearing the Zulus aii about, he let his body go under water and covered his head well up with grass. Here he remained some time, but presently he heard from the opposite bank voices shouting 'Come out, Jack; they have all gone. Come out, you fool!' in very fair English.

He was on the very point of coming out, but seeing a Kaffir with a shield on the opposite bank he thought alilwas not quite right and so remained where he was. At the same time he saw right opposite to him a Kaffir hiding like himself under the grass, and he remained watching this fellow until our arrival, when the Kaffir turned out to be one of the escaped waggon drivers. He was watching our man, but feared to move for fear he should be taken for a Zulu and shot.

The 150 men soon arrived and we set to work at once to collect the dead and dig an enormous trench in which to bury them; this took us nearly all day. About five p.m. I read the burial service over the dead; we fired three volleys and then resumed to camp with what little the Zulus had left in the waggons.

Nearly everything had been broken or tom to pieces, the tents being in shreds and the ammunition boxes broken to atoms, the mealies and flour thrown aii about the place. They had killed all the dogs save one, and that we found with an assegai wound right through its neck. We have it in camp and it is going on all right. We found one Zulu wounded at the laager; he was a very handsome - man. A bullet had hit him in the shin, broken both the bones, and nearly cut his leg off. He told us his friends were in a great hurry to get off for fear we should come from Luneberg; they took with them a man next to him with a body wound because he could walk; they told him that there were many killed and wounded.

This man has since died; he would not have his leg cut off. You will see where Moriarty's tent was pitched outside the laager. I hear that the Zulus surrounded this place, that Moriarty was seen coming out of his tent and immediately had an assegai into his back; he was then getting into the laager over a desselboom when he was shot. [in chest].

Falling onto his knees, he said, 'I am done; fire away, boys.' We found him lying on his face inside the laager, quite naked; he wasn't disembowelled. He was a fine big man with quite white hair, and seems to have been known, for we have since heard from a woman that has come in from Manyeoba that the white captain himself killed three of Manyanyoba's sons. [using his pistol].

We brought into Luneberg the bodies of Moriarty and Dr. Cobbin, who was also killed there, and they were buried the following day. Coming in from the Intombi, our men searched aii the mealies and long grass, and about three miles from the river they found a Zulu with a bullet wound which went in under his chin and came out at his right side, thro' his lungs. He says he was stooping down when he was shot. Another bullet has made a clean cut on his cheek and taken off the lobe of his ear; this man is going on all right. Close to him in a stream they found the dead bodies of the men who took the short cut; these we brought into i uneberg, and at nine p.m. we buried them by torchlight.

On the 13th I sent some mounted men to search ail over the ground for the twenty men we then had missing. They rode over a large extent of country, but saw no trace of anyone. The river was still very high, but going down.

On the 14th I found the river was very considerably lower, so on the 15th I sent out some men with oxen to try and get the waggons (twenty-one) into Luneberg; they succeeded in bringing all the waggons over the river on this side and brought in here ten waggons; they found three bodies in the river and a rifle or two.

On the 16th I sent out for the remaining waggons; they again found three more bodies and one rifle in the river, and brought into Luneberg the eleven waggons. On the 18th I rode out there and the river was so high that I had to kneel right up on my saddle to keep my legs dry.

We have found about the scene of this misfortune the bodies of thirty Zulus; no doubt they must have taken some away and nearly all their wounded Our loss [in the 80th Regt.] out of 105 all told is sixty dead and missing; one officer dead, four we buried here, forty-one at the Intombi River, and fifteen are still missing. No doubt the latter are in the river, and we may recover some more bodies when the stream subsides.

Redvers Buller, Moysey, Engineers, and Hamilton, 90th, have been over here from Kambula Camp to inquire into the misfortune; they went out with me on the 18th to see the spot. The first night they slept here our natives were all on the scare. Just as we had finished dinner, some Kaffir waggon-drivers came running in from the hill at our rear, where they generally go at night to sleep, saying they had come across an impi of Zulus.

Our men got hold of this and altho' I assured them that these Kaffirs had only seen some friendly Kaffirs and that the enemy could not possibly get on to the hill without our knowing it, their minds were still very uneasy, and about eight thirty off went a couple of rifles and all went into laager and fort; the nights are very dark and no doubt they fired off at imaginary Zulus.

Posted again, but about two hours later off went a couple more rifles and in they all came to the fort, and there I kept them for the night, and the rain I am sure well cooled down the excited ones by daybreak. These young soldiers are more bother than hey are worth. A fellow nearly let off his rifle last night at a log of wood, but an officer happened to visit him at the moment he was challenging it for the third time and so saved an alarm. This finishes, I hope, the affair at the Intombi River, and I trust this may be be the last time I have to write about it.

PRIVATE JONES

When we arrived at the river we found it swollen very much from the recent heavy rains so that no waggons could cross it, it being about 10 feet deep in the centre and over 100 yards wide. The whole of the waggons were on the other side awaiting us, and we set to and made a rough kind of raft to take us over.

On the morning of the 6th Capt. Moriarty ordered the A Company and 13 men of E Company with three mounted orderlies (Fisher, Tucker, and myself) to cross the river and camp. There we waited day after day for the river to fall until the moming of the 12th - a morning never to be forgotten by any of those who escaped back to Luneburg.

About 2 a.m. it began to rain very hard and continued until 4 when it ceased and a very thick fog came down the hills on each side of us. About this time one of the sentries reported hearing a shot, but a long distance off so we took very little notice of it. Most of us lay down again thinking to get another hour's sleep. But we had not been down long when one of the most frightful yells that ever issued from human throats alarmed the whole camp.

We instantly sprang up, seized the first rifle we could get, rushed to the waggons and poured volley after volley into the approaching Kaffirs, numbering some thousands. They must have crept upon our sentries unawares and murdered them before they could give alarm. After firing several volleys the Kaffirs broke cover and rushed the waggons.

Then commenced one of the most terrible hand-to-hand fights that has been known for years. But fight how we might we could have no chance, as the enemy at this time numbered over 4,000. We tried several times to reach the horses, but all to no purpose. All at once I heard a cry of 'We are surrounded', I looked around and saw to my horror that the Kaffirs had closed round us and cut us off from the river. Then the slaughter of our poor fellows commenced. I never thought I should live to write this, as death seemed to stare us in the face. How the few escaped that did is quite a miracle.

By the time that we reached the river only four of us remained! Brownson, Fisher, Sergeant Sansome and myself. [out of group of 10]. As soon as we reached it we threw in our rifles, the river ran so strong we could not take them with us. We then plunged in ourselves, followed by the Kaffirs. Brownson, after getting into the middle, was caught by the Kaffirs and speared. Fisher, Sansome and myself still kept together until we were within 25 yards from the side, when I had to dive underwater to escape three Kaffirs who were close to me.

When I rose to the surface I saw that Fisher had reached the bank, but just at that time a Kaffir came beside me, grasped me by the throat by one hand and uplifted the other to assegai me. I caught his wrist and I drew my sheath knife and plunged it between his ribs up to the hilt.

I remember nothing more until I found myself clinging to the bank on the Luneburg side of the river. I scrambled up and there found Fisher and Sergeant Sansome kneeling down under cover, recovering their breath. I noticed several fellows at this time in front of me making for Luneburg.

On looking down the river bank I noticed Kaffirs scrambling up in hundreds. We jumped up and commenced to run towards Luneburg. Before we had gone 20 yards the sergeant was shot through the back. After running a few miles we were compelled to stop and pull off our wet boots and trousers, as the Kaffirs were gaining on us. We then ran on until we came within two miles of Luneburg, when we were again compelled to stop and tear off our shirts to bind our bleeding feet, we then came on to Luneburg completely naked.

When we arrived here three of our company men. When they got in sight of the river they saw the enemy swarming up the hills. As they reached the waggons a frightful sight met their eyes, as the enemy had disembowelled all our poor fellows, and mutilated them so that you could not recognise one from the others. Everything that was on the waggons was thrown off and destroyed.

COLOUR SGT. BOOTH

My dear wife and children, You must please excuse me not answering your iast letter that I received about eight days since. I know you will all be thankful for the most miraculous escape I have had, and I know you and our children will be proud of your husband and father when you will see in the papers the account of the battle at Intombi River.

We left Luneburg on the morning of 7 March to escort a convoy of waggons, about some 24 in number. We arrived at the Intombi River, some six miles from Luneburg on the road to Derby, about 11 a.m. The river was very high and we could not cross it only on a raft that me and Mr. Lindop Lt. A. H. Lindopl and some of the men constructed, the rain coming down heavens hard, which continued for four days successively. I was acting Quarter-Master Sergeant for the 103 men, Capt. Moriarty, Lieut. Johnson, Lieut. Lindop, and Doctor Cobbin, also a lot of volunteers and nigger drivers. In all that was engaged in the battle was 154 officers, men, etc.; only about 41 men and some riggers arrived at Luneburg to tell the tale.

Mr. Lindop had gone to Luneburg the night before the battle, also Lieut. Johnson, and one man, Lieut. Harward came out to relieve them. About 4.30 a.m. on 12 March 18791 was awoke by hearing a shot fired in the direction of the mountains.

I should have told you we were under Mbelini's Cave, a notorious chieftain. Lieut. Harward called for me and told me to alamm the camp on the other side of the river - for there was me and Lieut. Harward and 33 men on one side of the river, the remainder on the other side. I called out for the sentry on the other side to alamm the camp; he did not answer me, but a man named Tucker came to the riverside and I told him to tell Captain Moriarty that a shot had been fired, and to alarm the camp. He sent word back that the men were to get dressed but to remain in their tents. I was in the commissariat waggon taking charge of the goods, I went in the waggon again and lit my pipe ant looked at my watch, it was quarter to 5 a.m. I put on my ammunition belt, and me and another man was smoking in the waggon when about 5 o'clock I heard another shot fired, and someone shout 'Sergeant Johnson'.

I looked out of the waggon, and I shall never forget the sight I saw. The day was Just breaking and there was about 5,000 Zulus on the other side. They were close to the tents and shouted their war-cry, 'Zu Zu'. They fired a volley into us on this side of the river, then they commenced assegaing the men as they lay in the tents. I rallied my party by the waggons and poured heavy fire into them as fast as we could, some of the men coming out from the other side of the river and coming across to us.

Crawford was one of them, he was the only man out of his tent that got across alive. Captain Moriarty and Doctor Cobbin was murdered in their tents, and most of the men also.

I commanded the party on this side as Lieut. Harward saddled his horse and galloped away, leaving us to do the best we could. When I saw all our men across, about 15 in number, all as naked as they was born, I sent them on Kaffirs crossing the river to try and cut us off, but we made good our retreat to a mission station, and expected to be outflanked there, but we fought our way to within a mile of Luneburg.

The distance we had to run and fight was nearly five miles, so you will have a guess how we were situated. We arrived at Luneburg about 15 minutes past 7 o'clock, losing nine on my side, and 46 on the other side was buried, and all the remainder was assegaied in the river.

A party went out to bury them on the same day, but they have been and taken them up again (i mean the Kaffirs) and skinned them. So we are ordered out again to go and bury them, we go directly, I am one of them. [Booth then lists the names of the forty-one killed, and another twenty-one who were missing, 'they must have been killed in the river'].

I am acting Pay Sergeant of a company now. There was a parade, and I and my small party was complimented on the bravery we exhibited in saving as many lives as we did, and bringing them in with such little loss of life on my side. I am mentioned in dispatches to the General and to Colonel Wood. there is also a letter sent to the editor of the Natai Argus, I will send you one when l get it.

Now, dear wife, I hope you and our children are

all well. I hope Lucy is better and that she was not so far

gone as you thought. Remember me to all enquiring

friends. With fondest love to you and all the chicks,

trusting God to spare me from all evil and grant me life to

see you again, I remain your loving husband,

A. Booth.

Casualties

British

Killed:

-

2 officers (Moriarty and Surgeon Cobbin)

60 N.C.O.s and men

2 European Conductors

15 native drivers

1 wounded Private

Zulu

Unclear - 25 bodies found around laager. Reports suggest around 200 killed to be realistic.

BATTLE PROFILE

It would seem as if this action was a case of 'it won't happen to me', as no real effort was taken to prepare the camp for the known threat of attack. Major Tucker makes reference to the enemy being all around, the column itself was raided by small groups of Zulu/Swazis, driving of some cattle prior to Capt. Moriarty's Company arriving and that a large enemy camp was a mere 5 miles away. [It is interesting to note that Major Tucker did not order the Capt. to relay the camp]

The construction of the laager was not ideal but understanding can be given due to the quagmire state of the surrounding area along the river, manoeuvring large waggons into position in torrential rain is no easy task even for a full Company.

The rising and falling river made it impossible to risk any waggons near it for fear of them becoming stuck or even washed away The defensive nature of the laager can be criticized to a point, gaps between waggons etc., but the failing really lies with the use of only 3 sentries which was wholly inadequate to properly guard the camp in enemy territory.

The Zulu/Swazi impi must be given full credit for their ability to get so close to the camp without detection, making full use of the tall mealie grass that surrounded the camp. No doubt the earlier shot was fired accidentallly by a warrior and it is easy to imagine the 800 or so warriors frozen in motion all straining to hear any signs of activity in the camp that would signal that their surprise attack had failed.

I'm sure the luckless warrior received suitable verbal suggestions as to what he could now do with his rifle from his comrades and officers.

As for Lt. Harwood, he was court-martialed for riding off and leaving his command. He was found not guilty much to the disgust of senior officers in the army.

WARGAMING - NTOMBE RIVER

The action is an ideal game for a 1-1 skirmish, the

numbers involved can be scaled down to suit pockets, 50

or so British and a representation of 400 or so Zulus 50%

or so single based.

The action is an ideal game for a 1-1 skirmish, the

numbers involved can be scaled down to suit pockets, 50

or so British and a representation of 400 or so Zulus 50%

or so single based.

Rules should be kept simple.

For sentries, roll a D6 dice to decide on numbers otherwise only have 3 as original. Roll a D10 dice to decide within what move scale attack will go in if required, then for each sentry, each move roll a D6 to see if they spot the impi and raise the alarm 2-5 no 1+6 yes.

A starting point should be chosen for the start of the Zulu/Swazi advance, the native player previously having drawn his impis attack formation, so if discovered he cannot )ust put his figs on the table anywhere.

If the sentry on Lt. Harward's raised the alarm, there should be a delay of one move on the Captain's side to fall in due to distance etc.

To recreate Sgt. Booth's fighting withdrawal, all

Zulu/Swazi figs within 12 inches of an organised body of

10+ British figs who have ammo should test for morale,

test in groups of 30-50, roll 1D6:

1-4 do not attack,

5 shadow group

6

attack.

The edge of the table should be the safety point for British figs. For Mealie and firing rules simply highest scores wins on a D6 plus and minus for officers/NCOs and for Zulu firing. You can introduce ammunition shortages and reloading problems for realism. You can mark on the base of each fig his total shots available.

For a good sheet of rules dig out Issue 12 of Wargarnes Illustrated, Jim Wallman produced a skirmish set of rules which is ideal for Ntombe River. Good luck. Will the British player dare to put his tent outside the laager? You should really.

Terrain and Figs

Terrain and Figs

All figs mentioned earlier will suffice nicely as would the waggons. The easiest way to represent the mealie fields is to use broom ends, which cost no more than £ 2.00 each, available at a local hardware store or DIY, cut the bristle off in chunks and stick them into some tetrlon or like. Base on thick card or thin wood of various sizes, paint base and their you have your grass. 1 broom will suffice for 15mm layout, 2 for 25mm.

More Ntombe River

-

Ntombe River

Ntombe River, Large Map (slow: 79K)

Ntombe River, Jumbo Map (slow: 129K)

Ntombe River Colour Diorama, Large (slow: 128K)

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 1 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1992 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com