Introduction:

On the 9th of February 1849 a revolutionary mob overthrew the government of Pope Pius IX and declared Rome a republic. The Pope withdrew into the Vatican, while many of his papal troops decided to switch sides and support the rebels.

Shortly thereafter, disguised as a common monk, Pius IX slipped out of the Vatican and fled to the fortress of Gaeta in the neighboring Kingdom of Naples, where he proceeded to call upon the Catholic world to crush the Italian revolutionaries.

France was first to respond to the papal call for aid, dispatching a force under General Charles Oudinot. On 25 April this army arrived at Civitavecchia, about 40 miles from Rome. On the following day, a French staff officer, Colonel Leblanc, arrived in Rome and met with the leader of the revolution, Guiseppe Mazzini.

Leblanc informed Mazzini that the Pope would be restored to power, despite the wishes of the Roman people. The revolutionary Roman Assembly, amid the thunderous shouts of "Guerra!, Guerra!", authorised Mazzini to use armed resistance against the French. The stage was set for the Siege of Rome.

French Army

The French army consisted of 9,000 troops and was moving to the town of Palo. Within Rome were 2,500 papal troops, 1000 National Guard and perhaps 1000 men of Guiseppi Garibaldi's Italian Legion. Garibaldi was worshipped by the common folk of Rome, and it is his presence and popularity that is largely responsible for the high morale that the defenders displayed over the course of the siege.

General Oudinot was under the impression, gained falsely from the inhabitants of Civitavecchia, that the italians would not fight. "We shall not meet as enemies either the citizens or the soldiers of Rome," he had told his officers. "Both consider us as liberators."

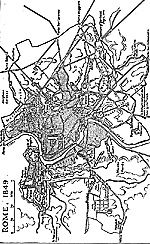

However, the citizens and soldiers of Rome had been busy rapidly constructing defenses atop the Janiculum Wall, a 17th century battlement that guards northern Rome from the Porta Portese on the Tiber to the walls of the Vatican Palace. It was here that the French were expected to attack, as this approach offered the most direct route to the Vatican and, through the St. Pancras Gate, the heart of the city.

Outside the walls, Garibaldi, who commanded the defense of the Janiculum quarter, had placed garrisons at the Villa Pamphili, Villa Corsini, and Villa Vascello: three key positions that commanded the approach to the St. Pancras Gate.

Shortly before eleven o'clock on the morning of 30 April, the French vanguard approached a stone watch tower on the summit of Vatican Hill. The scouts were only a little way ahead of the road columns, since they had been assured that the republican troops would surrender the city when the first shot was fired, if not sooner.

General Oudinot had ordered the columns to make for the Pertusa Gate, which according to the French maps, led directly into the Vatican, (what the maps did not show was that the gate had been walled up many years earlier.) As the leading troops approached to within one hundred yards of the gate, a cannon shot rang out, followed by another.

So firm was the French belief that the Itaiians would not fight that an officer remarked that the cannon volley must be the signal for noon. To their dismay, they were soon to learn otherwise, as the first shots were followed by more. Recovering from their surprise, the call for a general advance rang out, as the light French field guns unlimbered to return the fire mounting from the Janiculum wall.

Assault

Since Oudinot had neglected to provide heavy siege guns, or even scaling ladders for his troops, the assault consisted of loose columns of infantry rushing forward and attempting to climb the Vatican walls.

They failed and fell back to the broken ground beneath the hill, as other columns moved off to assault the Cavaleggeri Gate and the Angelica Gate. In both cases, the defenders met these assaults with a spirited and deadly fire that caused the French to fall back.

At this point, seeing the French attack falter and seizing the moment, Garibaldi sent 300 of his civilian volunteers forward from the Villa Pamphili supported by 1000 of his legionnaires in a bayonet charge against the French flank. However, the attack was disrupted by the presence of a sunken lane with steep walls, and beneath the arches of a nearby aqueduct, the student-soldiers ran headlong into eight companies of the 2eme de Ligne.

Surprisingly, when the excited young men opened fire on the regulars, and then fell on with the bayonet and shouting "Viva la Republica", the French fell back in astonishment. It did not take these seasoned troops long to sort themselves out and counterattack, and within a few minutes they had driven the students and legionnaires back to their positions and towards the Villa Corsini.

Fortunately for Garibaldi, a battalion of papal troops under Colonel Galetti arrived from the reserve, allowing him to rally his legionnaires. Shouting "Onward with the bayonet!", Garibaldi led his men across the grounds of the Villa Corsini and into the Villa Pamphili.

The Italians threw themselves upon the French, and in the words of a French officer, fighting "as wild as dervishes, clawing at us even with their hands," drove them into the deserted countryside beyond the aqueduct and the road back to Palo.

Garibaldi wished to follow up on the French repulse with an attack the next day, but Mazzini over-ruled him. Mazzini desired to win the republican French over to the cause of the revolution, and insisted that their captured soldiers, about 360, be treated as guests of the Roman govemment.

Guests of War

These "prisoners" were treated with elaborate courtesy, taken on a tour of the sites of Rome, and given food, wine, and even cigars before they were sent back to their regiments outside the walls. Along with the cigars, the Italians sent political tracts vilifying the "republican" government in France for attacking another republic, often citing the fifth article of the new French constitution: "France respects foreign nationalities. Her might will never be employed against the liberty of any people."

This diplomatic approach, after hostilities had already begun, proved fatal to the prospects of the '49 Revolution. Louis Napoleon, then President of France, and soon to become Napoleon III, felt that the defeat of Oudinot's force represented a slight to French military honour that could not be compromised. He informed the general, "You can be certain of being reinforced."

But the French needed to buy time for the reinforcements to reach Oudinot, so they sent Ferdinand de Lesseps to negotiate a ceasefire while they mobilised the necessary manpower. de Lesseps was unaware of this duplicity, but was cautious enough to add a proviso requiring the French govemment's ratification of any agreement.

To his suggestion that Oudinot's army remain where it was (outside of Rome) to protect the city from the converging approach of an Austrian as well as a Neapolitan army, the Italian Triumvirate agreed.

On 4 May, Garibaldi left Rome with about 2,300 men to confront the Neapolitan threat. After several days, and realising the dangers of a head on clash with a force twice his number, he conducted a night march towards the town of Tivoli, then turned and moved south to the village of Palestrina, thereby threatening the Neapolitan right flank.

The army of Naples and of King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies approached Palestrina on 9 May in two straggling columns, perhaps 5000 troops in all. Garibaldi attacked at once, catching the disorganised columns in the town and vigourously throwing them out of it. After three hours of hotly contesting the town, the Neapolitans retreated.

Return to Rome

Garibaldi returned to Rome, where negotiations continued, before marching out again, under the command of Colonel Pietro Roselli, a Roman. This time the column consisted of 11,000, and once more they were to attack the Neapolitans.

But Ferdinand had learned of the impending republican attack, including the large numbers of troops involved. Already discouraged from advancing on Rome by the presence of the French, the Neapolitan army was retreating. Garibaldi, in the advance guard and subordinate to Gen. Roselli, was determined that the Royal troops should not escape.

On the morning of 19 May the republican advance-guard, Garibaldi personally conducting the reconnaissance, discovered the Neapolitans on the Velletri road, south of the Alban Hills. On his own authority, he gave orders to engage the enemy and sent a message back to Roselli insisting on reinforcements. Roselli refused, preferring to consolidate the republican positions before attacking. The Neapolitans disengaged and withdrew across the frontier back into their own country.

There was a more urgent need for the army: the Austrians had occupied Lombardy and were quickly advancing through the Papal States, determined to restore Pius IX and his papal government. Mazzini felt compelled to recall Roselli and his troops to Rome.

Upon their return, the soldiers discovered that the genuine danger emanated not from the Austrian army, but from the French. Oudinot's reinforcements had arrived at the end of May, 11,000 men, including heavy siege batteries and engineers under the superlative General Vaillant.

Oudinot then abrogated the agreement arranged by de Lesseps, claiming that the latter had exceeded his brief and informed General Roselli that he would defer any attack "upon the place" until Monday morning. The Italians assumed that this meant the Roman outposts as well as Rome itself. They were wrong.

Oudinot later maintained that "upon the place" meant Rome proper, and he had therefore not precluded an attack on the Roman outposts on Sunday. This is precisely what he did.

At just before 0300 hours on 3 June French troops over-ran the unsuspecting volunteers who had bivouacked at the Villa Corsini. General Vaillant realised that an assault on the St. Pancras Gate would require proper saps and trenches to be pushed forward, and the villas that dominated the ground before the Janiculum were just what the French engineers needed.

Most of the Italians were asleep; assured by their leaders that no attack would come before Monday. The French brought up artillery, and the attack went in with the support of a preliminary bombardment. The garrisons were also swept out of the Villa Valentini and down the hill, with the French close behind.

Bells of Alarm

In Rome the bells were ringing the alarm. While crowds cheered them on, regiments of Papal troops, National Guard and the Italian Legion hastily rushed to reinforce their comrades on the Janiculum wall. Meanwhile, the garrison at the Villa Vascello under Colonel Giacomo Medici had held out despite being surrounded on three sides and under fire from the upper ftoors of the Villas Corsini and Valentini.

Garibaldi took charge of the situation. He was determined to counterattack and retake the two villas. He ruled out a flanking attack because the right flank of the Villa Corsini was protected by a high wall and the sunken lane and on the left flank by the French guns and a convent, which had been occupied by the French. The only alternative was a frontal attack.

The attacks were conducted with suicidal bravery throughout the morning, but to no avail. Even with the support of a battery of guns from the Casa Merluzzo atop the Janiculum wall, the Italians had to pour out of the narrow St. Pancras Gate, charge across 300 yards of open ground to the villa's boundary walls, close up to pass through the chokepoint at the gates, run up the drive which was narrowly flanked by dense hedges, and then rush up the steps of the villa itself; all the while under fire of the French sharp-shooters.

Once or twice the Italians did manage to gain entry to the Villa Corsini, and the sight of the French being tumbled out of the windows by the bayonet brought cheers from the spectators watching from the St. Pancras Gate. To no avail, as the French would withdraw to the grounds of the Villa Pamphili and regroup under cover of their guns before launching a ferocious counter-attack. Hundreds of Italians died crying "viva la republica!."

So devastating and disciplined was the French musketry, that one witness, seeing a body of a dozen Italians suddenly drop at the same moment, thought that they had all tripped on the rope-like vines that criss-crossed the Corsini drive. It was only when they did not move again that their fate became apparent.

With the failure on 3 June of the Italians to retake the Villas, the outcome of the siege was decided. The French were able to step up their siege operations against the Janiculum wall. Heavy artillery batteries were set up on Corsini hill, and the republicans were hard pressed to respond.

Within Rome, some recrimination of Garibaldi was voiced, but the majority of the blame was laid at Colonel Roselli's feet for failing to reinforce Garibaldi. Mazzini remarked privately that "Rome has already fallen."

Siege Lines

The action reverted to small skirmishes between raiding parties and the extension of the French siege works. More heavy batteries were set up on Monte Verde: these proceeded to further pummel the Italian positions.

Then, on 21 June, the French subjected the Janiculum defenses to a withering bombardment and, just after sundown, stormed the breaches that had been opened up in the walls. The Central Bastion and the Casa Barberini were captured, and the defenders were in such disarray that the French might have broken into the city. Garibaldi decided that a counter-attack could not succeed, and ordered his troops to fall back to the Aurelian Wall, a construction which dated from the time of the Roman Emperor Aurelius.

While his defenses may have been crumbling, they had not yet fallen. Setting up his HQ is the Villa Spada near the hill of San Pietro in Montorio, and retaining control of the Casa Merluzzo and St. Pancras Gate, Garibaldi realigned his artillery to cover his new positions. Here he waited while the Roman Triumvirate considered his demands that Rome be abandoned and the soldiers released from her defenses to conduct a guerrilla war.

On June 29, at about 0100, after having bombarded the defenses yet again, the French rushed the Aurelian Wall. One column overwhelmed the Casa Merluzzo, while another, having cleared the wall, spread out to encircle the Villa Espada and the St. Pancras battery. The Italians counter-attacked, and by dawn had retaken the Aurelian wall. With the French now in possession of the Casa Merluzzo and St. Pancras Gate, however, the Italians had no hope of holding their position.

The Revolutionary Triumvirs were unable to come to a decision: Mazzini had decided that the Republic should perish in flames, as a final gesture of revolutionary defiance; the Revolutionary Assembly was considering surrender. Declaring that wherever they went, Rome would be with them, Garibaldi made preparations to break out of the siege with those of the volunteers that were willing to chance it.

The Italian Legion departed Rome on 2 July. The French entered Rome the following day. Despite one or two tussles over the removal of their tri-color, the Italians appear to have been resigned to the defeat, and on the French part the soldiers behaved with restraint. There were few reprisals.

After a narrowly run pursuit, Garibaldi was able to escape to Piedmont and thence to the USA. Pope Pius IX was returned to power over the Papal States, which he was to retain until 1870, when the last French soldiers were withdrawn.

Wargaming the Siege and Uniform Information

Bibliographical Credits

Garibaldi and His Enemies by Christopher Hibbert

Peter's Kingdom by Jerrold Parker

Dictionary of Battles by Brigadier Peter Young

Related

-Finis-

Back to Clash of Empires No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Clash of Empires List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Keith Frye

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com