I've shown how the victors of WWI

had a natural tendency to employ at least

some of the material and doctrine of 1918

during the immediate post war period.

Germany, the defeated power, had

every reason to seek new and

innovative tactics and weapons.

I've shown how the victors of WWI

had a natural tendency to employ at least

some of the material and doctrine of 1918

during the immediate post war period.

Germany, the defeated power, had

every reason to seek new and

innovative tactics and weapons.

Even had they wished to do so, the Germans would have found it impossible to recreate the mass army and costly static defenses of 1914-18. The German army was limited to 100,000 long-term professional soldiers (with no reserves except for paramilitary police) by the treaty of Versailles. This same treaty also forbade tanks, poison gas, combat aircraft, and even heavy artillery!

Designed to cripple any future German war effort, these prohibitions may have been a blessing in disguise. German military thought was forced to be less restricted. Having no stockpiled weapons left over from 1918, German planners could study fresh ideas and develop weapons to' test these ideas. Evolving doctrine dictated technical development, which was the antithesis of the policies of the victorious armies. To conduct field trials, the Germans used mock-ups, or tested equipment and theory in secret within the Soviet Union.

I'm not saying the Germans started from scratch. No army can completely escape its past. But when it came to innovation, the Germans had a real advantage over their future enemies (who also happened to be their past enemies).

Traditional German tactics, going all the way back to the 1860's, favored flank attacks and encircling movements. Failing this, they favored "breakthroughs" which disrupted enemy organization and rear area support facilities. This led to two practices:

-

1. The Germans concentrated their

resources on a fairly narrow front to

achieve "breakthrough", unlike the

French or British who learned to attack

on a broad front to protect their flanks.

2. Such concentrations required detailed planning and integration of all weapons and arms "at battalion level or lower" to overwhelm local defenses. The infiltration (Stoss) tactics of 1917-18 reflected this view and were retained after the armistice.

Therefore, in spite of the Versailles restrictions, 1921 German field regulations concerning "Command and Combat of the Combined Arms" included the "Infantry Assault Battalions" and and the meticulous "Artillery Preparation" of 1918, but also "Close Air Support", "Poison Gas", and "Infantry Tank Support". Here, then, is an example ofthe German freedom to develop doctrine based on experience, without the restrictions of existing technology. These sophisticated regulations remained the key to German doctrine throughout the inter-war period.

Then there was the German tradition of "decentralized execution." German commanders traditionally moved about in the forward areas, assessing conditions and making tactical decisions based on their direct observations and conversations with small unit commanders "in the line." This enabled them to make their decisions clear to their subordinates and produce orders which reflected the "actual" tactical situation.

The speed at which orders could be implemented was also enhanced by the greater mutual understanding among German unit leaders. To this was added the efficiency of a common and clearly articulated doctrine as defined in "Command and Combat of the Combined Arms". Knowledge of the both the commander's intentions and the common doctrine reduced the need for detailed orders from above. The resultant flexability led to rapidity of decision and implementation ideally suited to fluid combat, i.e. mechanized operations.

Recap

To recap, we have seen the German experience with the psychological effects of tanks in WWI, Stoss tactics, massing on a narrow front, and decentralized execution. It would seem these factors would inevitably lead to "Blitzkrieg". Wrong!

Wholehearted acceptance of blitzkrieg did not occur until after the fall of France in 1940. Prior to that, the majority of senior German officers thought of mechanization as "useful" but too specialized a tool to replace ordinary infantry divisions. Once more the "traditional" viewpoint went down hard and slowly, just as in Britain, France, and elsewhere.

The most influential proponent of the blitzkrieg was Gen. Heinz Guderian. Guderian had considerable experience with the early use of radios in combat. He had served with radiotelegraph units supporting cavalry operations. The result was his insistence on radios in every German armored vehicle, in direct contrast to the French and early British where radios were limited to command vehicles. These armies considered hand signals and flags to be adequate for inter-tank communication in the heat of battle!

Generally, Guderian's early service taught him how hard it could be to integrate new doctrine and equipment and overcome institutional resistance to anything new. His staff work was concerned primarily with motorized transport.

The small size of the German army in the 1920's forced a dependence on mobility to shift limited forces rapidly from place to place. Oddly enough, it was British experience the Germans relied upon to learn about equipment they themselves did not possess themselves in large numbers. But their conclusions were developed independently from British trends. As seen in part one, the British were tending towards pure armor formations. Guderian discounted the usefulness of separate tank formations or even the mechanization of parts of the traditional arms. What he foresaw was an entirely new mechanized formation of all arms that would maximize the effectiveness of the tank. Only fully mechanized formations could sustain fully mobile warfare.

Guderian was not deterred by the general belief that antitank weapons had become too strong for tanks to overcome. He simply integrated anti-tank weapons into the mechanized combined- arms team. Early tanks were generally too small and unstable to carry effective highvelocity anti-tank guns, and existing anti-tank artillery had greater range, a higher rate of fire, and greater ease of concealment than tanks, making them difficult to engage.

German tankers were trained to avoid fighting enemy tanks or antitank guns and instead to exploit areas of little resistance. When they did encounter enemy armor, their doctrine was to fall back behind a screen of anti-tank guns deployed behind their spearheads and allow them to engage that armor from concealed positions.

This doctrine required mobile supporting arms, including large, well armed and organized reconnaissance units, both to lead the way and to protect the flanks of the advance and combat engineers to sustain mobility, Motorized and mechanized infantry and artillery were needed to reduce bypassed centers of resistance, support the tanks in the attack, and hold the ground taken. The whole force then required a supply and maintenance "tail" capable of keeping up with the advance as well.

The implementation of this policy was not without opposition and difficulty, however. The other branches of the German armed forces weren't going to take the formation of an entirely new arm lying down and demanded their share of motorization and mechanization. In the late 1930's the General Staff directed the motorization of all anti-tank units and one engineer company in every infantry division, as well as the complete motorization of four infantry divisions. In 1937-38 two independent tank brigades were formed solely for infantry support.

Then the cavalry formed four "light" divisions. These consisted generally of an armored recon regiment, two motor infantry regiments, one light tank battalion, and two towed howitzer battalions. This drain on resources frustrated Guderian's efforts and diluted his authority as he had no control over the motorized infantry or light divisions.

In addition, German tanks weren't up to the standard necessary for blitzkrieg. - Hitler's first priority in R&D during most of his regime was the Luftwaffe. This was due primarily to the intimidation value it gave him in dealing with other European politicians. Guderian, therefore, had to settle for tanks that were not entirely battleworthy.

The Pz I was basically a machinegun carrier, and the Pz 11 had little armor protection. These two vehicles made up the bulk of German armor units until after the battle for France in 1940. Their value lay in their being available in large numbers (with radios) early enough to allow extensive training exercises. These exercises led to the establishment of battle procedures to identify and solve problems, and to develop workable organizations and mobile support practices.

The panzer divisions were not completely ready in 1939, but they had gone through the first stages of organization and training. They were pretty much alone in this.

Close Air Support

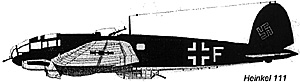

Finally, there was the advantage of close air support of ground troops. Initially the Luftwaffe favored strategic bombing and air-superiority like other nations' air arms, and close support was neglected. It was the Spanish Civil War that changed these priorities to some extent. German forces aiding Franco had used a limited number of obsolete fighters in a ground attack role with considerable effect. By the fall of 1938 there were five German ground-attack aviation groups. Ernst Udet persuaded his superiors to produce a few close- support dive-bombers based on the U.S. Navy's Curtiss Helldiver. The result was the JU-87 "Stuka".

The Stuka proved both accurate and demoralizing to ground troops. In addition, a small number of air-liaison detachments were added to infantry corps and Panzer division HQ's in the main attack. These could pass requests for airsupport on to the Luftwaffe and monitor air recon reports. They could not guide aircraft onto targets and were not trained to do so. Generally requests for air support had to be submitted in advance and the call might or might not be honored! In 1939, on-call air support was in the future.

The tradition of combined arms integration was continued and updated in the German army between the wars. Guderian's primary failure was his denial of the need to provide armor and motorized equipment for the mass of the army, which remained essentially dependent on human and horse feet for mobility. His primary success was to keep the majority of Germany's mechanized assets concentrated in combined arms units instead of being spread in small pockets throughout the army, where whatever good effect they might have would be diluted to insignificance.

In September of 1939, twenty-four of thirty-three tank battalions and almost 2,000 of the 3,000 tanks available were concentrated in six panzer divisions. The contrast with other countries, where large numbers of tanks were spread out in infantry-support and cavalry roles, is striking!

More Combined Arms

Back to Citadel Summer 1999 Table of Contents

Back to Citadel List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Northwest Historical Miniature Gaming Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com