Blockade Running

Blockade running until 1865 was a very profitable business and at least in the beginning was not extremely dangerous. The Union was plagued by not having enough ships to adequately patrol, much less control the 3,500 mile Southern coast. The chances of being caught by the Union Navy in 1861 were 1 in 9 and in 1862 the odds were only 1 in 7. By 1863, blockade running had

developed into a fine art; the main reason being the profit factor: salt which sold for $6.50 a ton was worth $1,700 a ton at Richmond and coffee had jumped from $249 a ton to $5,500.

Blockade running until 1865 was a very profitable business and at least in the beginning was not extremely dangerous. The Union was plagued by not having enough ships to adequately patrol, much less control the 3,500 mile Southern coast. The chances of being caught by the Union Navy in 1861 were 1 in 9 and in 1862 the odds were only 1 in 7. By 1863, blockade running had

developed into a fine art; the main reason being the profit factor: salt which sold for $6.50 a ton was worth $1,700 a ton at Richmond and coffee had jumped from $249 a ton to $5,500.

Thus the Confederate government simply could not control the running of the blockade. In 1863 the Union blockade was beginning to make its presence felt; the odds of being caught were 1 in 4. However, all was not as bleak as it would seem because in 1864 the blockade runners brought in:

-

8,632,000 pounds of meat

1,507,000 pounds of lead

1,933,000 pounds of saltpeter

546,000 pairs of shoes

316,000 pairs of blankets

520,000 pounds of coffee

69,000 rifles

2,639 packages of medicines

43 cannon

All this had been paid for in part by $5,296,000 of exported cotton. It must be remembered that as the war progressed the blockade runners were forced to settle for lesser known ports in the South because the major ones either were effectively sealed off or they had been captured. All of these factors meant that, in some cases, vital supplies spent long months in warehouses before the necessary transportation could be arranged. Thus, the Confederacy was again penalized because of an inadequate navy.

The threat to the Confederacy's naval power in 1861 came not from the Atlantic Ocean but from the rivers, principally the Mississippi. It was here that the Union Army and naval forces began their Anaconda strategy which was to ultimately prove the complete weakness and disorganization of the Confederate Navy.

To begin with, the Confederate Navy had no policy concerning the defense of the rivers and so the responsibility fell to the Army which assumed that any naval forces in their area of responsibility were then under anny control. The Naval District Commanders were almost always junior in rank to their army counterparts.

Another sore point was coastal defense. While principally the army's responsibility, the Navy organized special batteries to defend certain strategic targets, but the dividing line of command responsibility was never clear.

Another sore point was coastal defense. While principally the army's responsibility, the Navy organized special batteries to defend certain strategic targets, but the dividing line of command responsibility was never clear.

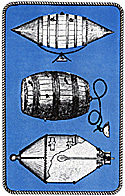

At right, Confederate mines. Some were converted wooden kegs filled with powder and primed to explode on contact. More elaborate were electrically triggered from shore, like the bottom model. A mine was responsible for sinking the USS Tecumseh in Farragut's assault on Mobile Bay, 1864.

On the question of transportation, the Army had control of most of the major rail lines; the Navy had a very difficult time in transporting armor, armament, supplies, and crews by rail. Making a bad situation worse, the Navy frequently tore up unused stretches of track to be used as makeshift armor on their ironclads.

Neither the Army nor the Navy understood or appreciated the situation that each found itself in. The Army (according to the Navy) had a bad habit of drafting skilled laborers that the Navy and other industries critically needed to keep the war effort alive. There are many accounts of ironclads falling into enemy hands or having to be destroyed simply because of a lack

of adequate labor or materials.

In the South there was only one company that had done any prewar construction of armament, machinery, and the necessary gear for warship construction: the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia. This single industry had the ability to consume between 20,000 and 24,000 long tons of pig iron, but it never had as much as 8,000 long tons of pig iron at any time during the war.

The Confederacy possessed more pig iron works. According to the 1860 census there were 39

furnaces in the South producing 26,262 tons of pig iron: 17 in Tennessee, 4 in Alabama, and 2 in Georgia, with the remaining 16 in the other Southern states. All Southern states except Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi had iron deposits of varying quantity and quality, but lost the most important iron producing areas (Kentucky, Tennessee, and western Virginia) early in

the war.

Thus, the operations of the Confederate Navy can be summed up in three categories: 1) coastal and harbor defense; 2) blockade breaking and running; and 3) river defense. The first category was what all the ironclads were destined for and usually they proved unsuitable

because of the shallowness of the waters and the lack of maneuvenng space.

Also the civilian population placed their faith in these ironclads to such a degree that land defense was relatively sparse. The second category was not the responsibility of the ironclads because of their limited range, mechanical unpredictability, unseaworthiness, and

cramped conditions. Occasionally an attack by an ironclad did succeed in lifting the blockade for a short time but never longer than a few days. The responsibility for blockade running was left in the hands of private individuals with the already discussed outcome.

Of course, the commerce raiders had their place but their contribution was of questionable impact. In the third category the Confederate Navy was wholly unprepared. In fact, there are cases of riverboats being used with nothing more than cotton bales as armor. All too often

the Confederates were forced to use their ironclads to attempt to stop the Union onslaught on the river, something for which the Southern ironclads were unsuitable.

With the loss of New Orleans in April, 1862, and the fall of Vicksburg in 1863, the Mississippi was effectively opened for the Union and divided the Confederacy. It is

realistic to say that the South was doomed to defeat simply because of the inability of Southern leaders to appreciate the necessity of naval planning and construction.

Galant but Unequal

At right, the CSS Tennessee. The canvas canopy shielded the ironclad from the fierce sun.

While at times the South had the element of surprise on

its side, the North had the overwhelming numbers and the facilities to effectively replace any losses while the Confederate Navy losses were permanent ones.

The South attempted to destroy the ever-growing numbers of Union ships which were blockading her ports and challenging her use of the rivers. In the case of the Southern Navy it can be stated that there were too few ironclads and they were too late to have any lasting

effect on naval operations. The South reintroduced many types of naval warfare that had not been used since the Revolutionary War such as the submarine, though its effect at this time was slight.

The Confederate Navy was simply too new for the South. The machinery and technology that it demanded were not available in the South in large enough quantities to build and support the kind of navy that the South needed to win the war.

Confederate Navy 1861-1865: Part 1

The Confederate Navy, though at times gallantly led, proved to be an unequal opponent for the Union Navy because the South was not able to wage war on their enemy but instead were forced into a constant defense.

The Confederate Navy, though at times gallantly led, proved to be an unequal opponent for the Union Navy because the South was not able to wage war on their enemy but instead were forced into a constant defense.

Confederate Ironclads Ship Construction Data Armament Armor Notes ALBERMARLE launched 26 May, 1864, at Halifax, N.C. 6 guns (?)

4 in. sunk Nov., 1864, by Confederates ARKANSAS Oct. 1861, to 15 July, 1862, at Fort Pickering, Miss. 2 8" rifles 4 42lbrs 1 in. iron plate covered with T rail backed with wood 24" thick

sunk in attempt to breakout from Vicksburg, 6 Aug 1862, speed: 6 m.p.h. ATLANTA converted Winter 1861-1862 in Savannah, Ga. from merchant steamer Fingal, commissioned Atlanta, 22 Nov. 1862 2 - 7 inch, 2 6.4-in. guns, spar torpedo, ram 17 in. oak and 4 in. armor surrendered to Union forces after ran aground in attempt to break out of Savannah Harbor, 17 June 1863 BALTIC converted from cotton lighter in Mobile, Ala, Dec. 1861

1 42pdr, 2 32 pdr, 2 12 pdr howitzers, ram not available armor used on Nashville CHARLESTON Charleston, NC., 1864, money raised through Ladies Gunboat Society

2 9 in. smoothbore, 4 6.4-in. Brooke Rifles not available

destroyed by Confederates 18 Feb., 1865, Charleston, S.C.; speed 6-9 m.p.h. CHICORA launched 23 Aug. 1862, Charleston, NC 2 9-in. Dahlgrens, 2 7-in not available destoyed by Confederates, 18 Feb., 1865, Charleston, S.C.;

speed: 3 knots EASTPORT 31 October, 1861, Cerro Gordo on Tenn. River

work was never completed by CSN captured Feb., 1862, by Union forces; completed as Union

ironclad FLORIDA (formerly SELMA) name changed Sept., 1862 2 9-in. Dahlgrens, 1 8-in. Columbiad, 2 32pdrs not available sunk Mobile Bay, 1865; sidewheeler FREDERICKSBURG built in Richmond, Va.; one of Ladies GunBoats 8 guns (?)

not available burned by Confederates, 2 Apr, 1865, near Richmond, VA., to prevent capture GEORGIA private citizens built in Georgia, 20 May, 1862 2 6-in., 2 8-in. Columbiads 2 layers RR iron destroyed by Confederates in Savannah, Ga, 1864; not

self-propelled HUNTSVILLE keel laid at Selma, Ala. Fall, 1862 1 Brooks rifle, 1 6-in., 4 - 32 pounder 4-in. iron sunk by Confederates, April, 1865, Mobile, Ala., speed: 3 knots JACKSON (also MUSKOGEE) launched Jan 1864 at Columbus, Ga. 8 guns (?)

not available sunk by Confederates 1865, in Charleston, Va. LOUISIANA launched 6 Feb., 1862, New Orleans 3 9-in. smoothbores, 4 8-in., 2 7-in rifles 2 layers of RR iron sunk 24 April, 1862, by Union naval forces off New Orleans MANASSAS built by private interests in New Orleans; taken over by C.S.N. Oct., 1862 1 9-in. Dahlgren 2-in. iron run aground April, 1863 in New Orleans area, speed: 6 knots MISSISSIPPI launched Apr 8, 1862, at New Orleans; never fully completed

20 guns (?) 2-in. iron plate burned 24 April, 1862, to prevent capture

MISSOURI launched Shreveport, Ala 14 April, 1863 1 11-in. Dahlgren, 1 9-in. Dahlgren, 1 32pdr 2 layers of RR iron surrendered to Union forces, 1865, stern paddle wheel for locomotion, speed: 6 knots MOBILE converted to ironclad at Yazoo City, Ala 1862 3 32pdr, 1 32pdr rifled, 1 8-in. 12 in. wood backing 2 layers of RR iron never completed, destroyed by Confederates, July 1863 NASHVILLE built Aug.1864, Montgomery, Ala. 2 bow pivots, 1 stern pivot, 4 broadside guns 5 foot wood backing 6" iron plate sunk 12 April, 1865, to

prevent capture; doublesided paddle wheels NEUSE constructed on Neuse River, SC, launched 27 Apr., 1864 1 Brooke Rifle, 1 6-in., 4 32pdr 4" RR iron sunk March 9, 1865 to prevent capture NORTH CAROLINA built at Wilmington N C.; launched Spring 1864

6 guns 24-in. wood backing 6-in. iron sunk at her mooring at Smithville S.C. due to worm-eaten hull, speed 3-5 knots PALMETTO STATE built at Wilmington NC.; launched Spring 1862 2 9-in. Dahlgrens, 2 7-in 24 in. timber 12 in. planking, 2 in. iron 18 Feb 1865, blown up to prevent capture, Charleston, SC, speed: 5 knots RALEIGH built at Wilmington N C.; launched Spring 1864 6 guns (?) 24 in wood backing 6-in. iron 7 May, 1864, ran aground; broke back attempting to get free RICHMOND constructed in Richmond, Va., 1863 4 guns

2 in iron, 24 in. timber, 12-in. planking burned April 1865, in Richmond, Va to prevent capture SAVANNAH built in Savannah, Ga, 1863 2 7-in., 2 6.4-in.

2 in iron, 24 in. timber, 12-in. planking burned 21 Dec. 1864 to prevent capture in Savannah, Ga., speed: 6 knots TENNESSEE completed at Selma, Ala., Feb. 1864 4 10-in. Columbiads, 2 7.5-in Brooke Rifle 9-in. wood backing 6-in. iron sunk Mobile Bay, 1865, speed: 6-8 knots TEXAS work started Richmond, Va., 1864 1 Brooke rifle, 1 6-in., 4 32pdrs 4-in. iron unfinished; captured by Union forces in Rldunond, Va., 1865

TUSCALOOSA completed at Selma, Ala., 1864 1 Brooke rifle, 1 6-in., 4 32pdrs 6-in iron sunk 1865 in Mobile Bay, speed; 6 knots VIRGINIA Gosport Navy Yard, Norfolk, Va., from hull of Merrrimac 24 July,1861-20 Feb 1862 6 9-in. Dahlgrens, 2 7-in, 2 6.4-in, ram 24" wood, 4 -in. iron March 1861, two battles with Union naval forces in Norfolk Harbor, sunk by Confederates May 1862 to prevent capture, speed: 6-8 knots VIRGINIA II Richmond Va.; launched June 1863 6 7-in.

18-in. wood, 4-in. iron destroyed by Union naval forces in Richmond, 1865

Back to Campaign #90 Table of Contents

Back to Campaign List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by Donald S. Lowry

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com