The strategic purpose of the Confederate military during the Civil War was basically twofold: to protect the Southern states from outside invasion, and, failing in the first, to make the war so costly for the North that it would eventually be forced to give up from exhaustion.

The strategic purpose of the Confederate military during the Civil War was basically twofold: to protect the Southern states from outside invasion, and, failing in the first, to make the war so costly for the North that it would eventually be forced to give up from exhaustion.

The Confederacy also tried to prove its causus beli in order to be granted diplomatic recognition by a European country. Of the three branches of the Confederate military (army, navy, and 600-man Marine Corps) the army was the only branch to even come close to the stated goal.

The Confederate Navy's responsibility was the protection of the harbors and coast lines from blockade, and, hopefully, the establishment of a local superiority over the Federal Navy. The Confederate Navy was left with a blank check on methods and means to accomplish these aims. In February, 1861, the Confederate "Navy" amounted to some ten ships carrying fifteen guns.

The Union Navy on the other hand listed 90 vessels of all classes in the Navy Register for 1861. However, of these 90 ships, 21 were unfit to go to sea at all, 27 were laid up in various navy yards in need of extensive repairs or not ready to be launched, and 28 were in foreign stations, some as far away as China.

The Union Navy on the other hand listed 90 vessels of all classes in the Navy Register for 1861. However, of these 90 ships, 21 were unfit to go to sea at all, 27 were laid up in various navy yards in need of extensive repairs or not ready to be launched, and 28 were in foreign stations, some as far away as China.

Large US Map (slow: 172K)

Jumbo US Map (extremely slow: 408K)

So actually the Union Navy only had fourteen ships close enough to be called upon in case of emergency. Needless to say, the Union Navy could not hope to blockade a coastline some 3,600 miles long with what was on hand.

Thus in April, 1861, the two antagonists were as close to equality as they were to be for the remainder of the war. Of course, this situation would not remain static for long.

Mallory Appointed

On February 21, 1861, the Confederate Congress appointed Stephen R. Mallory as Secretary, Department of the Navy. He was in all probability one of the most well-qualified appointees to the Confederate cabinets. Mallory was experienced as an admiralty lawyer in his home state of Florida, and he served for a time as the chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee while he was a United States senator.

Thus the Confederate Navy gained a man who was capable of building the Southern Navy. The only questionable part of his character was an incident before the actual termination of diplomatic relations between the North and the South. The incident involved the capture of Fort Pickens and the Pensacola Navy Yard, both in Florida. The general opinion early in 1861 (while Buchanan was still president) was that these two areas could be easily taken for the South; but, through the work of Mallory and several of his associates, they were able to persuade both the Florida legislature and the President that these Union possessions were in no danger unless they were reinforced without warning.

This action was something for which many Southerners never forgave Mallory. As one of his subordinates Mallory appointed Duncan M. Ingerham to head the Bureau of Ordinance and Hydrography. He was to set up the Southern munitions works and armament industry.

The general feeling in the South was that, after April, 1861, the President of the United States could not hope to make a blockade effective because the English would not stand for losing one of their major markets of raw cotton. Unfortunately for the South, what was forgotten was that the abundant harvest of 1860 had already been exported and that, except for a long war, the English would have no immediate economic interest in the South.

Building Ironclads

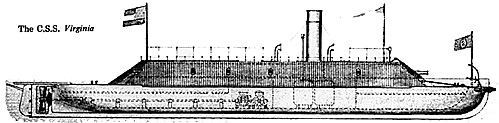

The decision by the Confederates to build ironclads was not entirely unexpected because the United States Navy had been interested in the idea since shortly after the War of 1812. With the capitulation of the Gosport Navy Yard after the secession of Virginia, the Confederate Navy secured one of the few major navy yards it was to possess. In all, the Confederates captured more than one thousand naval guns of all calibers including 52 Dahlgrens, but ultimately more important than this was the capture of the 3,200 ton USS Merrimac, a steam frigate. Thus the Confederacy had the beginnings for their most famous ironclad, the CSS Virginia.

The Confederacy lacked many of the blessings that its northern neighbor had. For example, it lacked an adequate railroad system, proper naval repair facilities, rope walks, and, most of all, iron and steel mills. In 1861-1862 there were three major iron industries in the South. These were the Tredegar Iron Works, the Bellona Iron Works (both in Richmond, Virginia), and the Selma Naval Works in Selma, Alabama. These facilities became the mainstay for the Confederate armament industry throughout the war. In spite of the difficulties faced by the Southern Navy, work was begun on the CSS Virginia. In addition to the Virginia, work was also begun on four more "coastal ironclads."

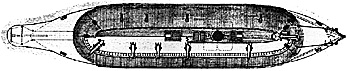

The plan of these five was basically the same; they were all to be fitted with sloping side armor with their fore and aft decks slightly awash. This design was the brainchild of John L. Porter who was one of the most "progressive" thinkers in the South at this time. Porter's chief idea was to build an ironclad capable of ocean voyages, but the inability of the South to manufacture reliable machinery hampered him.

In late 1861, the work on the ironclads proceeded slowly. The main problems encountered were those of lack of adequate materials and of trained labor to do the necessary technical work. Nevertheless, the CSS Virginia was the primary ship on the completion list; even though the navy attempted to expedite mattes, work on the Virginia was halted due to bottlenecks in the Confederate rail transportation system.

Virginia

It had taken the Confederate naval engineers little more than a month to refloat and make the USS Merrimac ready to be reconstructed as an ironclad, but it took the Confederate iron industry and the railroads over eight months to get the necessary material to the Gosport Navy Yards. On her completion in February, 1862, the CSS Virginia was a force to be reckoned with; her armament consisted of six 9-inch Dahlgren smoothbores, two rifled 7-inch cannons, and

two 6.4-inch Brookes rifles.

It had taken the Confederate naval engineers little more than a month to refloat and make the USS Merrimac ready to be reconstructed as an ironclad, but it took the Confederate iron industry and the railroads over eight months to get the necessary material to the Gosport Navy Yards. On her completion in February, 1862, the CSS Virginia was a force to be reckoned with; her armament consisted of six 9-inch Dahlgren smoothbores, two rifled 7-inch cannons, and

two 6.4-inch Brookes rifles.

The Virginia was plagued by problems as late as March 5, 1862. For example, she was too light -- the eaves of her armor plate were on the water line instead of below it. The ship was extremely slow with a maximum speed of six to seven knots. She was extremely hard to handle; in fact, the steerage was so poor that it took from thirty to forty minutes to turn 180 degrees.

Even with her shortcomings, the CSS Virginia was to be the foremost ironclad of the Confederate Navy.

The Virginia was plagued by problems as late as March 5, 1862. For example, she was too light -- the eaves of her armor plate were on the water line instead of below it. The ship was extremely slow with a maximum speed of six to seven knots. She was extremely hard to handle; in fact, the steerage was so poor that it took from thirty to forty minutes to turn 180 degrees.

Even with her shortcomings, the CSS Virginia was to be the foremost ironclad of the Confederate Navy.

About noon on March 8, 1862, the CSS Virginia officially "got under way" and started steaming toward Newport News. When the Confederates reached Hampton Roads, they ran into Union blockading forces which then consisted of five wooden-hulled frigates.

In the ensuing battle which lasted five hours, two Union ships were sunk, a third damaged, almost 300 Union sailors were killed, and 100 were wounded.

In the ensuing battle which lasted five hours, two Union ships were sunk, a third damaged, almost 300 Union sailors were killed, and 100 were wounded.

Large Hampton Roads Map (slow: 140K)

The CSS Virginia and supporting craft of three unarmored gunboats suffered no major damage except to two guns on the Virginia and her ram.

Monitor vs. Merrimac

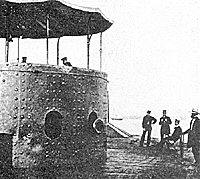

On the following moming both Union and Confederate spectators expected to see the CSS Virginia finish the remaining ships of the blockading force and then either head toward open sea or turn toward Washington, D.C. As the Virginia approached the scene of the battle, her pilot spotted a strange flat craft with a turret mounted on the center, which was recognized as the USS Monitor, which had been finished in time to take part in the battle.

The role assigned to the Union craft was to protect other Union wooden-hulled ships in the Norfolk Harbor area. Thus, the Monitor did not act as offensively as she might have under different circumstances. As the battle continued neither side was able to seriously damage the other, but the CSS Virginia was finally forced to retire because of the falling tide. The result of the battle was a tactical victory for the Union, because the Monitor had succeeded in protecting the remainder of the Union blockading fleet in the Norfolk Harbor area.

As both sides retired to lick their wounds, the wooden ship passed into obsolescence. The mere existence of the CSS Virginia caused a great deal of concern in the Union camp, especially where the plans of General McClellan were concerned.

As both sides retired to lick their wounds, the wooden ship passed into obsolescence. The mere existence of the CSS Virginia caused a great deal of concern in the Union camp, especially where the plans of General McClellan were concerned.

At right, the Monitor's damage was limited to a few dents.

End of the Virginia

With the beginning of McClellan's peninsular campaign the military situation in northeastem Virginia held bleak prospects for the Confederates. In fact, in just a little over a month (May 9, 1862) the Norfolk Navy Yard was in danger from Union advances. Within 48 hours the CSS Virginia was to be no more -- she was deprived of her home port and had too deep a draft

to be able to cross the shoals at that time of the month, so the Confederates had no choice but to scuttle her in order to prevent her capture.

Despite this setback, Mallory's aspirations were not finished. As early as August of 1861, Secretary Mallory had been visited by Asa and Nelson Tift of Georgia who, even though they were not ship builders by trade, possessed plans for ironclads that could be built without any curves and that, according to their statements, could be built by any house carpenters. Thus, by the time of the sailing of the CSS Virginia, four other ironclads were on the stocks, and others were in the advanced planning stage. It is possible that Secretary Mallory was confident to put his faith in several "home built" ironclads.

It would be foolish to think that Mallory relied upon the manufacturing ability of the South alone to challenge the North at sea. He realized that, if the war was to continue for any long period of time, the South would have to get outside support and possibly intervention to break the blockade.

To attempt to "hurry" this possibility Secretary Mallory appointed Commander James Dunwoody

Bulloch to the post of chief naval agent. It was Bulloch's task to secure by nearly any means European naval aid for the Confederacy. The naval strategy that Commander Bulloch attempted to follow in his dealings with the European power, especially England, was:

2. To construct a new class of warship in a foreign port to challenge the Union navy for control of the Southern coast.

3. To create and operate a fleet of special blockade runners that would be

government-owned and manned by southern naval personnel.

At first, these objectives seem entirely possible within the scope of present day logic;

however, in actuality, it was these principles that would doom the South to defeat.

Cruiser Theory

The work of the CSS Alabama, CSS Florida, and CSS Shenandoah shows the

actual implementation of the first objective. These three ships probably did more than any other Confederate ships to terrorize the Union merchants; in fact, they came close to driving Union commerce from the high seas. Would the situation have been different if these

ships and others like them had been able to interdict the commerce of the Union?

In all probability the outcome of the war would have not been markedly different because innumerable foreign shippers stood ready to take up the slack in the American shipping. If, under the circumstances the Confederacy had attempted to stop, search, and/or sink

these neutral vessels, then the South would have been risking war with a European power -- something that she could ill afford.

There was one more flaw in the "cruiser theory" which was excellently stated by Mahan in his

Influence of Sea Power on American History. He asserted that the possibility of the feats of the Confederate cruisers being repeated was very unlikely. He noted that the work of those cruisers was "powerfully supported" by the Union decision to give top priority to the blockade and that, had the number of the cruisers been multiplied ten times, they could not have

stopped the intrusions of the northern fleet along the southern coasts; that injury to the merchant marine did not in the least influence or retard the event of the war.

In trying to build "a new class" of ships in foreign ports the South was somewhat successful; however, the only highly operable class of ships that the South gained

from foreign builders were ships like the Alabama whose sole purpose was to raid Union

merchantmen. On the proposal of building ironclads abroad the South was completely disappointed. Originally Secretary Mallory had hoped the Major Caleb Huse could obtain vast quantities of arms from England in early 1861; then, when Huse was not obtaining the expected

results, Major Edward C. Anderson was sent by President Davis in a vain attempt to gain some means of helping the Confederacy.

Only when Commander Bulloch was sent with the orders of the Secretary of the Navy to

"settle the situation in England" did things begin to happen. It is not that Bulloch's predecessors shirked their duties, but Bulloch knew the right people in England to get tasks done.

One of the many tasks that Bulloch accomplished was to purchase the merchant ship Fingal and load her with supplies which were delivered to Savannah, Georgia authorities in November, 1861, much to the displeasure of Union authorities both in England and aboard the blockading fleet. The cargo of the Fingal for the Navy Department was:

The Fingal was then to undergo the transformation into the CSS Atlanta and

ultimately suffer her demise in 1863 when she ran aground in an ill-fated attempt to break out of the Union blockade surrounding Savannah. Commander Bulloch did obtain the cooperation, for a price, of various ship builders in England to build ships for the Confederacy; one of the major contributors to this cause was the Laird shipyards of Liverpool who aided the Confederate cause

considerably.

If the Confederacy could not purchase ironclads, Secretary Mallory envisioned the goal of having them built for the Southern Navy. To achieve this the Secretary of the Navy sent Commander James H. North to attempt to purchase a French Glorie-class

ironclad but he was unsuccessful.

The only European ironclad to be built especially for the Confederacy was the CSS Stonewall which sailed from Europe early in 1865 and then broke down several times en route arriving in time to be surrendered to Union authorities after Lee's surrender.

IronClad Living Conditions

Then, there were living conditions aboard the ironclads of day -- they were all crowded, extremely hot in summer and cold in winter. There was inadequate ventilation, they tended to leak, and the below-deck areas were all but uninhabitable. It was therefore possible that the crew of any ironclad of that time arriving after a transoceanic voyage would be

completely useless for any mission.

Another factor which the Confederates had apparently failed to take into consideration was that an ironclad needs a home port from which to operate and that it would be impossible to expect an ironclad to operate like the Shenandoah whose sole purpose was to raid commerce. The ironclad could be bottled up in any port when she ran low on supplies or

had mechanical difficulties.

English aid was one of the keys to Southern victory; however, the only way that the South would be able to obtain it was to prove that she was able to hold her own against the North. Prime Minister Palmerston soon lost interest in direct support of the Confederate cause when

he realized that the economic aid would have to be backed up with military intervention, something that neither he nor Queen Victoria wanted.

Thus the Confederacy in her dealings with Europe did achieve some successes, but they were too few and in some cases too late to alter the preponderance of mechanical and military might that the North could and did bring into the struggle. Whether President Davis or Secretary Mallory realized this is doubtful because as the Southern logic was interpreted during those times, they were sure that if the war lasted long enough that some nation in Europe would come to their aid. This opinion became more unrealistic as the war continued.

It was late in the war before Mallory considered putting the blockade runners under the control of the navy and, until this was actually achieved (which it never was), the blockade runners would continue to be more interested in making fortunes for themselves than in

aiding the Confederacy. For this reason they loaded their ships with goods that would have the highest commercial resale value in the South. In fact, their profits rose from 100% in 1861 to 1,500% in 1864-65.

Confederate Navy 1861-1865: Part 2

1. To obtain cruisers as soon as possible to harass the commerce of the Union and to compel the dispatching of Union men-of-war to hunt these cruisers.

1,000 short rifles with cutlass bayonets

1,000 rounds of ammunition per rifle

500 suitable revolvers with suitable ammunition

2 4 1/2-in. muzzle-loading guns

200 made-up cartridges, shot and shell per gun

2 2 1/2-in. breech-loading guns

200 rounds of ammunition per gun

400 barrels of coarse cannon powder

Back to Campaign #90 Table of Contents

Back to Campaign List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by Donald S. Lowry

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com