In issue 7, I reported on a visit to the battlefield of Medina de Rioseco made 190 years and one week after the event. During the same trip, I was fortunate enough to be taken to the field of Talavera 188 years and 51 weeks after the historical battle. The weather, as you might expect was HOT and probably little different from its character all that time ago. I could barely move with a light shirt, jeans and a bottle of water in my knapsack. How anyone could have fought a battle in red or blue wool jackets (no one seems certain of what material Spanish uniforms might have been made) with heavy backpacks and a weighty musket to carry -- not to mention the ammunition -- I shall never know.

In issue 7, I reported on a visit to the battlefield of Medina de Rioseco made 190 years and one week after the event. During the same trip, I was fortunate enough to be taken to the field of Talavera 188 years and 51 weeks after the historical battle. The weather, as you might expect was HOT and probably little different from its character all that time ago. I could barely move with a light shirt, jeans and a bottle of water in my knapsack. How anyone could have fought a battle in red or blue wool jackets (no one seems certain of what material Spanish uniforms might have been made) with heavy backpacks and a weighty musket to carry -- not to mention the ammunition -- I shall never know.

Sadly, the Spanish transport ministry had, a few years previously, driven a motorway through part of the battle field (that held by the Spanish under Cuesta) which has marred it but, thankfully, not ruined it. The man who accompanied me on my visit was largely responsible for causing the Spanish Government to erect a huge memorial to the participants just beside the motorway. He was, at the time of the visit, Spanish ConsulGeneral to the USA but, when the monument was erected, he had recently returned from another posting and was in Spain when groundworks reportedly uncovered numerous bones of what was apparently a mass grave.

There is some uncertainty over whether any bones were actually uncovered or whether those knowing of the area's historical importance embellished the "actualite" to prompt action in reducing the damage caused by the works. Whatever the truth, my host. Leopoldo Stampa, was in a position and had the drive and incentive -- he is a keen

researcher into the War of Independence -- to get something done. Let me quote his own words from the Foreword to his book [1] :

On 8th September 1988, in one of my encounters with the president of the `Wellington Society' in Spain. Stephen Drake Jones, he told me a story that awoke my curiosity. During one of their excursions to the location of the battlefield of Talavera de la Reina, he said that they had found remains that closely resembled a common grave, uncovered by the bulldozers that were levelling the area where they were building the Madrid-Caceres motorway. Drake Jones was suggesting that something had to be done to avoid that from happening. A little earlier, 'The Times' had published a letter of his, expressing a complaint about the destruction of the terrain on which the battle took place. But it had all stopped there.

It was evident that something had to be done. Nobody anticipated that they could interrupt the road works; this was not an option; so we agreed that I would inform the Defense Ministry of the facts and, if the finding of remains were confirmed, propose that these would be collected and a monument raised in respect for those who fought there.

I was, at that time, advising the Defence Minister for International Affairs. Historical areas were not one of the subjects which fell within my responsibilities, but I believed that the matter needed to be addressed. I recollect that, that same afternoon. I informed the General Director of Public Relations and Defence Information of the nature of my conversation with Drake and of the proposal that we were making.

Afterwards, I submitted the initiative to the Minister, P. Narcis Serra, who approved the idea of erecting a commemorative monument. The news did not take much time to get around, thanks to the articles written by the correspondent of the 'Daily Telegraph' in Madrid, Tim Brown, on 9th and 10th September and of the 'ghost' in the Spanish Defense Magazine in its October issue.

For a few weeks the public works Ministry ordered a rigorous investigation of the area and arrived to make explorations in the area next to the Portina brook which, because the ground is softer, could supposedly contain the common graves. Nothing was found.

Monument

However the idea of erecting the monument went forward and, from the Defense Ministry, we coordinated the activities of the project with The Embassies of the United Kingdom, France, Low Countries and Germany, so that its inauguration took place on 3rd October 1990, in a ceremony that counted on the assistance of the Spanish Ministry of Defence, the Spanish and British Army Chiefs of Staff, various colonels of Spanish, British and French Regiments of the largest part of the units which took part in the battle, the Ambassadors of the contending countries and some of the descendants of the protagonists at the time such as the Dukes of Wellington and Albuquerque. The Spanish Defense Magazine, in its issue of November of that year gave wide publicity to the ceremony.

Battlefield

The field itself is probably well enough known to most wargamers interested in the period but descriptions from Oman [1], interspersed with my comments may help to assist visualising the ground:

"The position which Wellesley had selected as offering far better ground for a defensive battle than any which could be found on the banks of the Alberche, extends for nearly three miles to the north of the town of Talavera. It was not a very obvious one to lake up, since only at its northern end does it present any well marked features."

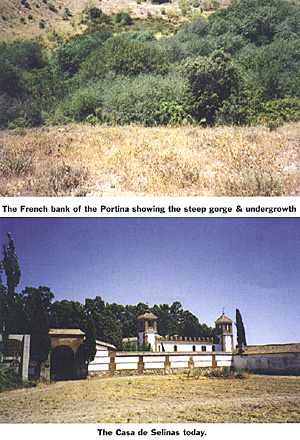

"Two-thirds of the position lie in the plain, and are only marked out by the stony bed of the Portina, a brook almost dried up in the summer, which runs from north to south and falls into the Tagus at Talavera. In the northen part of its course this stream flows at the bottom of a well-marked ravine, but as it descends towards the town its bed grows broad and shallow, and ceases to be of any tactical or topographical importance.

Indeed, in this part of the field the fighting-line of the allies lay across it, and their extreme right wing was posted upon its further bank."

For a mile and a half beyond the northern end of Talavera the ground covered by gardens and olive groves is perfectly flat..." See my comments above.

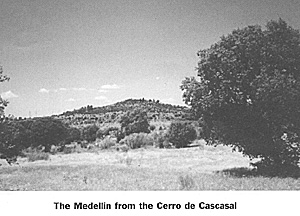

"...[the ground] then commences to rise and swells up into a long hill, the Cerro de Medellin. This height runs from east to west, so that its front and not the full length of its side, overhangs the Portina ravine. Its loftiest point and its steepest face are presented to the declivity, while to the west and south it has gentle and easily accessible slopes .... This hill, the most commanding ground in the neighbourhood of Talavera had been chosen by Wellesley as the position of his left wing. It formed, including its lower slopes, about one-third of the line which he had determined to occupy."

The first French infantry attacks were put in motion across the Portina to the south of the Cerro de Cascajal where, currently, the vegetation is fairly substantial. This may go some way to explaining why Leval's division got ahead of their comrades - they were advancing at the shallowest part of the Portina and where the vegetation is presently less pronounced. Oman suggests they had a greater tangle of cultivated vines and olive groves than their compatriots to pass but this would seem to be a reason for their being less advanced rather than more so. Notwithstanding all this, their columns were considerably disordered by their passage of the terrain.

From my observations of the ground, I have a strong view that some of the sufferings of both sides was due to the nature of the undergrowth which, if anything like it is now, would not only have impeded progress but both sight and order.

Nearer the town, the Pajar de Vergara redoubt is virtually undetectable. Although it has, apparently, been identified, I was unable to locate it for certain. It played an important part, however, in helping to secure the Spanish position which was never seriously threatened, their army being observed and contained by Milhaud's dragoons.

However, when Leval's Germans had delivered their final, abortive attack. some of the Spanish infantry left their positions to engage them. This suggested a fairly considerable threat to Joseph's left since, if the Spanish,

who had resisted steadily when attacked near the redoubt, had attacked en masse the French cavalry would have been insufficient to hold them.

As a final word from Professor Oman, I reproduce his notes on the Topography of Talavera:

"I looked over the proofs of the last three chapters, seated on the small square stone that marks the highest point of the Cerro de Medellin, after having carefully walked over the whole field from end to end, on April 9, 1903. The ground is little changed in aspect, but the lower slopes of the Cerro, and the whole of its opposite neighbour the Cascajal hill, are now under cultivation. [Not in 1998 - Ed.]

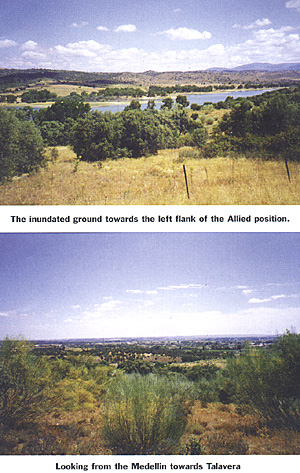

The former was covered with barley nine inches high, and the rough vegetation of thyme and dry grass, which the narratives of 1809 describe, was only to be seen upon the higher and steeper parts of the hill, and on the sides of the ravine below. The latter is steep but neither very broad nor particularly difficult to negotiate. Even in April the Portina had shrunk to a chain of pools of uninviting black water. The ditch fatal to the 23rd Light Dragoons, in the northern valley, is still visible [Inundated by 1998 - Ed.].

In its upper part, where the German regiment met it, the obstacle is practically unchanged. But nearer to the farm of Valdefuentes it has almost disappeared, owing to the extension of cultivation. There is only a four-foot drop from a field into a piece of rough ground full of reeds and bent-grass, where the soil is a little marshy in April. I presume that when the field was made, the hollow was partly filled up, and the watercourse, instead of flowing in a well-defined narrow ditch, has diffused itself over the whole trough of the ground.

In the central parts of the field the Portiha forms a boundary, but not an obstacle. Where Cameron and the Guards fought Sebastiani's 8,000 men, the ground is almost an exact level on both sides of the little stream. There is no 'position' whatever on the English bank, which is, if anything, a little lower than the French. The Pajar de Vergara is a low knoll twenty feet high, now crowned by a large farmhouse, which occupies the site of the old battery. [This was not in evidence in 1998 but I could have been in the wrong position - Ed.]

The ground in front of it is still covered with olive groves, and troops placed here could

see nothing of an advancing enemy till he emerges from the trees a hundred yards or so to the front. On the other hand an observer on the summit of the Cerro de Medellin gets a perfect bird's-eye view of this part of the ground, and could make out the enemy all through his progress among the olives. Wellesley must have been able to mark exactly every movement of Leval's division, though Campbell could certainly not have done so. In the Spanish part of the line the groves have evidently been thinned, as there are now many houses, forming a straggling suburb, pushed up to and along the railway, which now crosses this section of the line. In 1809 Talavera was still self-contained within its walls, which it has now overstepped. The Cascajal is practically of the same height as the main eastern level of the Cerro de Medellin but the triple summit of the latter is much loftier ground and standing on it, [It is now private property and one must seek permission from the owner living in the private house atop the hill - Ed.] one commands the whole of the Cascajal - every one of Villatte's battalions must have been counted by Wellesley, who could also mark every man along the whole French front, even into and among the olive groves occupied by Leval's Germans. Victor on the Cascajal could get no such a general view of the British position, but could see very well into Sherbrooke's line. Hill's troops, behind the first crest of the Cerro de Medellin, and Campbell's in the groves must have been much less visible to him. There is a ruined house, apparently a mill, in the ravine between the two Cerros. As it is not mentioned in any report of the battle, I conclude that it was not in existence in 1809. [I saw no such building in 1998 - Ed.]

The Pajar de Vergara farm is also modern, and the only building on the actual fighting-ground which existed on the battle-day was evidently the farm of Valdefuentes, which is alluded to by several narrators. French and English."

Casa de Salinas

It is not the purpose of this article to detail the entire battle or terrain but, to assist those who would like to wargame it. I provide the Orders of Battle.

As a footnote, there was an engagement at the Casa de Salinas, a ruined house with a small tower, on 27th July, between Donkin's Brigade (whom Wellesley was accompanying) and Lapisse. I read, not long ago, that the house was now demolished and the site hard to find. This is incorrect. Sr. Stampa told me he had found the house quite easily -- as we did once again -- and it has been restored. On a previous visit, he had been invited in by the owner but, unfortunately, had insufficient time to accept this kind offer. Also, much criticism has been levelled at the Spanish for failing to force the Alberche river on 23rd July. Having visited the site, I can understand the reluctance of the Spanish. The river is, according to Oman [4] "...fordable in many places..." indeed, the French, themselves, had crossed shortly before the arrival of the Allies. The French, though,

had crossed unopposed and their subsequent position commanded the bridge and any fords which the Spanish might have used.

The bridge itself (unchanged since 1809 except for having been partially destroyed) is decrepit, narrow and exposed. I did not seek for the fords and so can not comment on the situation of these.

[1] Sanudo, J. J. & Stampa, L. - "La Crisis de una Alianza" pub. by Ministerio de Defensa 1996, Spain

Talavera de la Reina 28th July 1809

The monument, erected in memory of the combatants of Talavera, was putting into relief once again the need to delve into the events connected with that episode. This made me get in contact with Col. J. J. Sanudo, the rigorous nature of whose investigations into the War of Independence, were known to me."

I subsequently met "Juanjo" Sanudo and have been corresponding with him and reading copies of "Researching & Dragona", a military historical research journal of which he is joint editor, to keep abreast of his work in researching the battles and Spanish Army. The Spanish, French and British military establishments, not to mention the people of these nations, owe these gentlemen a vote of thanks that, at last, a memorial exists to the brave soldiers who fought not just at Talavera but in all the engagements of the Peninsular War.

The monument, erected in memory of the combatants of Talavera, was putting into relief once again the need to delve into the events connected with that episode. This made me get in contact with Col. J. J. Sanudo, the rigorous nature of whose investigations into the War of Independence, were known to me."

I subsequently met "Juanjo" Sanudo and have been corresponding with him and reading copies of "Researching & Dragona", a military historical research journal of which he is joint editor, to keep abreast of his work in researching the battles and Spanish Army. The Spanish, French and British military establishments, not to mention the people of these nations, owe these gentlemen a vote of thanks that, at last, a memorial exists to the brave soldiers who fought not just at Talavera but in all the engagements of the Peninsular War.

This is putting it mildly; I am amazed that Wellesley thought it represented a position at all. For some distance from immediately outside the town (which is now considerably extemded from its 1809 boundaries) nothwards is virtually a flat plain with substantial vegetation.

Where the Cerro de Cascajal, a stony eminence, faces the lower slopes of the Medellin hill, the Portina has steep, high banks with vegetation in the form of mature shrubs and trees. On my visit, the bed was completely dry but the brook represented an obstacle extremely disordering to infantry and would, I suspect have been impassable for other arms. It is relatively close to the position of Hill's and Sherbrooke's divisions and the French artillery sited on the Cerro would have had some easy targets.

The troops (Hill's Division) located near the mid-height of this position would have been on ground with a considerable slope away to their front and might even have had some difficulty maintaining their equilibrium. Near the foot, the slope is less pronounced. The hill commands the entire field for observation purposes. As a choice to anchor the left, it is certainly the best available, although reserves would have been needed to avoid outflanking manoeuvres (these were, indeed, present in the form of the cavalry of Fane, Anson and that of the Spanish under Albuquerque, plus Bassecourt's Spanish infantry in the foothills of the Sierra de Segurilla). This more northern area has now been inundated to provide water for the region and can not be accessed.

Topography of Talavera

Topography of Talavera

FOOTNOTES

[2] Oman, Prof. Sir C. - "A History of the Peninsular War" Vol II, Oxford University Press 1903

[3] Sanudo, J. J. & Stampa, L. ibid.

[4] Oman, Prof. Sir C. ibid., pp 488 - 491.

Back to Battlefields Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com