For more than 600 years the search had been on to locate the site where the Roman Army had been annihilated. Early in the 16th Century, when the story was becoming celebrated, the Lippischer Wald was renamed the Teutoberger Wald, and in 1875 a monument to Arminius was erected on the supposed site of the battle near Detmold. Now in 1999, archaeologists are confident that some 12 years of research and digging has resulted in confirming the location of this most important chronicle in Germany's history, in essence, the birthplace of the German nation.

For more than 600 years the search had been on to locate the site where the Roman Army had been annihilated. Early in the 16th Century, when the story was becoming celebrated, the Lippischer Wald was renamed the Teutoberger Wald, and in 1875 a monument to Arminius was erected on the supposed site of the battle near Detmold. Now in 1999, archaeologists are confident that some 12 years of research and digging has resulted in confirming the location of this most important chronicle in Germany's history, in essence, the birthplace of the German nation.

Work has now been going on for some 11 years excavating the sites which, using the most sophisticated of modern metal detectors, an English officer, Major Tony Clunn, had extensively surveyed during 1987 - 1990. This included researching and studying of old maps, documents of great antiquity, and, most important, it was all carried out with the blessing, assistance, and guidance of the German museum and archaeological authorities.

This was not the first time the Detmold position of the battlefield had been challenged. Archaeologists and historians had previously offered up some 750 alternative sites, but never before had the evidence so strongly favoured a new location. Extensive desk research led to the area, but the actual site was pinpointed almost by accident. A month after arriving in Germany in 1987 to begin a tour of duty with the Armoured Field Ambulance unit in Osnabruck, Major Clunn began what was to prove many months and years of surveys and research. There however, were many long laborious days when it seemed the finds was the odd Roman coin or artefact. It had been well established by the resident country archaeologist, Professor Wolfgang Schluter, that not one Roman coin had been recovered from the Osnabruck area during his thirteen years in office.

Major Clunn's story began to unfold shortly after visiting the local museum where he first met Professor Schluter. He was naturally very cautious, but he decided to take the officer at face value. After hearing that his main interest was focused on Roman history and coins, he suggested Major Clunn might start his searches in an area some 20 kilometres to the North of the city, simply saying it was worth further study. Among the documents and old papers consulted as part of the research on the area was a series of 19th Century maps and a thesis by a 19th Century German historian, Theodore Mommsen.

Like many other historians in Germany before him, Mommsen believed he had correctly identified the area which was the probably site of the "Teutoburger Wald" Varus battlefield. His thesis was based on the fact that the resident landowners of the area, the (Baron) Von Bar family, had accumulated a large collection of Roman silver and gold coins, a good majority of which were from the reign of Augustus Caesar. Mommsen had originally been informed the coins had been found by farm workers in the local fields over the previous centuries, (the Von Bar family tree can be traced back to the early I 1Oth Century), and accumulated as such by the Von Bar family. However, he was also informed, perhaps as an adopted defensive stance, that a great many of the coins had been collected from finds made all over Northern Germany, and not necessarily from the local parish area. Nevertheless, he maintained his theory but was never able to advance it in the absence of further evidence.

Having studied Mommsen's theory Major Clunn had noted from information provided him by Professor Schluter that a very old road know as the "Old Military Road" (Heerstrasse) ran through the area. He therefore centred his main point of reference on a small crossroads in the middle of the Parish area, and it was from here that his investigations began in earnest.

By June of 1987, Major Clunn had made an intensive recce of the complete area of the Military road running through the Kalkriese area, and had made a careful evaluation of the best and first line of investigations and surveys using metal detectors. At this early stage he had identified and marked what he considered to be three key areas of rising ground, one either side of the military road, and a small knoll lying proud of the northern extremities of the hills some 1,000 metres away to the south.

However, at this stage, and from a number of possible old find sites, he selected one that had all the hallmarks of success, a lone Roman coin found in 1963 by a youngster playing in a field in the near vicinity of the military crossroads. Having found the family concerned, identified the field, and decided on his search pattern, he made his first survey on 5th July 1987. On that weekend he recovered three Roman denarius. With the Professor away on holiday, he continued his search the following weekend, whereupon he recovered a further concentration of some 90 Roman silver coins. The following week he delivered them to Professor Schluter, obviously astounded, and greatly impressed at this success.

Once the coins had all been re-packaged by the Museum assistants, Professor Schluter opened up the first line of communication with the `Munz Kabinet', a department of the Kestner museum in Hanover. This was managed by one of the world's leading experts on Roman and early coinage, Dr Frank Berger, a relatively young but vastly experienced scholar and the resident official at the coin museum.

Dr Berger had always had an avid interest in the coins that had been recovered, particularly from the Osnabruck area during 17 and 1800's, and had written a thesis on those early finds.

Dr Berger had always had an avid interest in the coins that had been recovered, particularly from the Osnabruck area during 17 and 1800's, and had written a thesis on those early finds.

During that time many of those coins had been collected by the 'Von Bar' family. As the oldest land-owning family in the Kalkriese area they could trace their lineage as far back as far as 900 AD, and they still maintained large tracks of land in the district. Strangely enough, my first own large find had now also been found on their lands.

It had always been considered that the greater majority of the coins recovered during the 18th and 19th Centuries had been accumulated over a long period either by the family buying individual small lots of coins from all over Germany, or taking in odd coins from their own farms and farm workers found during the harvesting and ploughing seasons.

By 1939 their Roman coin collection had become fairly impressive, certainly for the northern regions of Germany, and was comprised of many silver and copper coins, and a few gold Aureus. Up until 1945 the collection had been maintained and kept in the newer of the two family Schlosses (Castles) in Kalkriese, know as Gut Barenau, (the older original family Schloss at Alte (old) Barenau, a little over 1 kilometre distance away, dated back to 1305). Regrettably however, the whole collection was stolen during the final months of the war, apparently by occupying Allied forces. No trace had been found of any of the collection until much later in 1990, when Dr Berger uncovered some startling revelations concerning come of the missing coins. (See Chapter 10). However, until its theft, all of the collection had been carefully listed and cross-referenced, enabling experts, including Theodore Mommsen, to debate the real source of the coins and the reason for their deposition in Kalkriese.

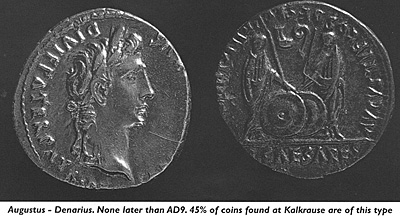

As a result of these lists there emerged the first remarkable clue that something far greater was afoot then just the find of a singular coin cache. In Hanover Dr Berger quickly went back to all his reference books to re-check the original lists of the Von Bar collection, and noted that there was an uncanny similarity between that accumulation and the cache that I had just recovered. It was not so much the comparison between alike coins, but more the clear similarity in the spread of the age of the minting eras, in particular that found evident in the mass of silver denarii. The more he looked at the graphs of the age spread of this coinage the more convinced he became that the Von Bar collection could never have been an accumulation made over many years from many districts in Germany but was unequivocally a collection that had been made in the immediate area of the Von Bar estates in Kalkriese.

The situation was that two very similar caches had been registered in the same area, and both from the same era. In neither collection were there coins that had been minted later than AD 14, and of those minted AD I-14, the greater majority were in pristine condition, as if they had been issued and lost a very short time after minting. The mint marks on these coins shoed them to have been made in 2BC-AD I in Lyon (Lugdunum) and issued immediately after 2BC.

Dr Frank Berger quickly diverted his attentions to another interesting source of information on the movement of Roman troops during their invasion and occupation of Germany, and to study again the other coin finds that had been made over the preceding centuries. One of the main Roman Lagers (Forts) that had been positively identified and excavated during the late I 800's was the key fort of Haltern. It was one of many main Lagers established by the Romans on the east-west axis through the German heartland centred on the River Lippe.

From archaeological excavations of this camp, a few thousand coins had been recovered. Although there was a marked ratio increase in the number of copper coins found there in comparison with the original Von Bar collection, and Major Clunn's new cache find, it would be natural for a Lager camp to use and retain more base copper coinage. But, once again, the denarius coin graphs shoed a remarkable similarity in the era, age spread and condition of all three accumulations; in the original Von Bar collection, and now the new cache.

Once Dr Berger had completed the initial and absorbing studies into the remarkable coincidence of age and condition between all three accumulations, he found himself confronted with an unassailable fact; undoubtedly some of the Roman troops occupying Haltern during that period had somehow, and possibly for some good reason, most certainly moved through the area of Kalkriese during the same year, and judging by the comparable condition of the Augustan coins, in the same season.

The very clear and concise Roman historical archives as written by Tacitus, the Roman historian, and Cassius Dio, had highlighted in their records thatVarus had spent the early part of AD9 in Haltern (indeed Varus' own personal mint marked coins had been found there during the excavations of the 1800's). These records also described how he then deployed to summer quarters, possibly out along the Lagers on the Lippe towards the German Highlands and ultimately to his summer camp, most likely at Minden, where he remained until the end of the season. Both he and his Legions, the 17th, 18th and 19th eagles of Rome never returned.

It was always believed that the Legions moving back west to the Rivers Ems and Rhine from the central northern plains bounded by the River Weser had done so on a military road/marchline along the northern edge of the hill feature running from Minden, to the north of Osnabruck and on to the west. Further research into this Theory tended to support such an idea, mainly due to the recovery of scattered coin finds and artefacts along the lien of hills itself, and other German historians from the 19th Century (Hartmann ad Von Altenasche for example), strongly advocated the existence of two main routes between the rivers Ems and Weser. Nevertheless, the fact remained, that coin finds had been made in fairly large quantities in the Osnabruck area, particularly to the immediate north of the city. The recovery of yet another cache only strengthened the supposition that there had been a strong Roman military movement into and through the area, but from which direction into Kalkriese if not due east from the Weser?

During the autumn months Major Clunn spent many hours in the museum with Professor Schluter and his staff, pouring over old records and maps of the areas surrounding and find site, and also spent a great deal of spare time searching the Kalkriese fields. Even at this early stage it was obvious that the first main task was to ascertain where people and troops might have moved through the area in former times, and to identify the routes they had taken. Although the old military road cutting across the moorlands initially seemed the obvious answer, Major Clunn was already getting a different picture. He had marked old coin find sites of times gone by onto more modern maps. The result was an interesting form of scatter effect between the Kalkriese Berg and the old military road.

Old maps were studied carefully to locate field names of common interest; The Roman Wall, the Gold Field, Silver Corner, Bikks Camp, and many more with a high degree of interest value from Mommsen's notes. He joined those from the central area and those that linked into the military road, transposing the information through a natural line of march to the east. An interesting feature resulting from these exercises; the finds further afield in the lands lying to the south and south-east, some 30-40 miles from the main site of interest at Kalkriese, indicated a possible line of march during Roman times well up from the accepted areas of concentration of main Roman activity lying to the south, and the River Lippe.

Over the next six months, well into the start of Spring 1988, the officer produced countless bags of unusual finds of various artefacts, including more scattered silver denarius from the areas immediately surrounding the original coin find site; each time museum staff enthusiastically examining these bags of finds.

During the spring and summer he maintained his efforts on the large fields, even moving over the canal into the area some 500 yards short of the crossways. Slowly but surely a cohesive pattern began to emerge from the recurring coin and artefact finds. Lines began to appear linking the road running east-west around the Berg through the knoll to the military road also running eastwest through the moor about 1500 yards away to the NW The picture was somewhat reminiscent to that of a small start burst, with the stars all bursting out in one direction. There was every indication that a large contingent of people had splayed out from the area at the apex to the field and the knoll, fanning out a in a 90 degree arc north and north-west down to the cross-ways, the military road, and the lands beyond, perhaps fleeing from an unknown horror.

On 12th July 1989, on his son's birthday, exactly two years after he had made the first major coin find in Kalkriese, Major Clunn returned to the apex of the woods which feel away from the large knoll on the edge of the Kalkriese Berg Here he recovered the first copper coin to be found outside those registered from the Lager at Haltern which bore the rare mint mark of Imperial Augustus Caesar.

The half As coin was inspected and catalogued by Dr Berger in the Munz (Coin) Kabinett in Hanover, and was stated to be one of the most important coin finds ever to be made in Northern Germany. The mintmark stamped into the coin was one of the rarest Imperial varieties.

From some 1,100 copper coins recovered from Haltern during the archaeological excavations of the 1800's and 1900's only 11 had been found with Varus' personal mint mark stamped on the, even though it was known that he and his Legion had lodged there for some considerable time during the years leading up to 9AD. None had been found along camps on the Lippe, no one had been found in the Detmold area where the Statue of Arminius stands today, one had been found anywhere else in the North German plains and Teutoburger Wald, except now, in Kalkriese. They were soon to be found in numbers telling a different story........

The find of the half As was the key that finally started to open the door. After it has been inspected and catalogued by Dr. Berger, he confirmed it was a rare copy with the Imperial stamp mark of Augustus Caesar. Encouraged by his information, the archaeological team in Osnabruck went into overdrive to further Major Clunn's searches in Kalkriese.

From 1988 Dr Schluter had permanently employed two of his staff armed with Fisher detectors in a continuous day in day out survey of all the outlying fields and areas that Major Clunn had previously researched and surveyed, but always keeping clear of his immediate work areas around the knoll of the Kalkriese Berg. Now, with the recovery of such an important find, the Professor decided that more intensive searches had to be carried out in the immediate area of the single coin site itself.

Armed with the knowledge that Major Clunn had already pinpointed many deep metal source readings on the far side of the wooded knoll in the open ploughed field, Professor Schluter then decided to initiate a new programme for his archaeological team. This programme was linked to Major Clunn's original surveys. Professor Schluter had now realised that major archaeological works in the Kalkriese area were justified.

Major Clunn had done much cartography work of the area during the preceding years, drawing lines of thought onto the maps, presenting ideas as to possible lines of march, carefully linking up both old and new coin find sites, and always the same starburst effect presented itself, bursting out to the west and north-west. These lines all emanated from the bottom of the Kalkriese Berg knoll, and were now supported by the find of an Imperial coin of Augustus.

In liaison with members of the Museum team and the officer, Professor Schluter formulated a comprehensive plan. It would combine the implementation of exploratory archaeological slit trenches starting up in woods on the bottom reaches of the western side of the knoll, moving through the woods up over the rise and ultimately to the open ploughed field on the other side. Further detector surveys on sites in the woods surrounding the knoll, previously recede by Major Clunn the year before, were to be re-visited by both he and the now highly expert and active museum search team under command of Herr Klaus Fehrs.

The search was now on in earnest. A full ground investigation of the wooded knoll area was to be carried out before the onset of winter, starting with a series of small slit trenches to be dug in the apex area of the knoll. A full dig ream was employed, but due to the difficult nature of the terrain, with trees and heavy undergrowth in abundance, heavy-duty machinery would initially be unable to get in to the epicentre of the excavations. Manual labour with shovels and the

like was therefore to be the main methods for the task. Having given the necessary instructions for the outline work to commence, Professor Schluter now had to secure further authority for the incursions to be made into the Kalkriese fields and woodlands.

After a month of exploratory digs on the wooded knoll, Professor Schluter's team made their first real find, a full perfect As of the Emperor Augustus Caesar with a full stamp mark of Publius Quinctilius Varus. With Major Clunn's find of the Imperial coin, the team now felt positive they were on the right track. Over the next few months they continued their slit trench excavations through the wooded knoll, finding many Roman bronze fibular, further copper coins, including more with Varus' personal stamp mark.

The series of excavations had now proceeded to the very eastern edge of the wood, and it was here that after a final slit trench was dug the team found what looked like the profile of a sunken earth wall. Professor Schluter decided it was time to move out into the field where Major Clunn had made his first deep trace tests the year before. A large excavation was made, initially 150 metres long by 5 metres wide. The Professor did now know what to expect, but hoped to continue the link up with the start of the earth wall in the woods. In the late winter and early spring of 1990 as the team dug deeper and deeper, they detected many metallic signals becoming stronger and stronger as they dug down through the earth to the sand bed below. The oxidised clump of iron that came out of the ground proved to be a ceremonial parade mask, resembling the profile of the Emperor, Augustus Caesar. It awoke the imagination of every learned archaeologist and school of historical interest in the whole of Germany. Headlines now proclaimed the finding of the battle site of the Lost Legions of Varus as the most important historical find in German history. Much to his amusement one journalist compared Major Clunn's achievements with those of Schlieman when discovering Troy (although in retrospect the comparison with ill conceived, as Schlieman had driven through seven or eight layers of important historical strata to get to the treasures he found!) However, the true visionary was obviously Professor Schluter, who had seen and realised the greater potential of the site.

Since various archaeologists and historians had scoffed at Professor Schluter's expert supposition that place actually this was the true battle site, and had retained their own theories as to the location of the "actual" battle, this find somewhat spoiled their own ideas, professional aspirations and written journals.

Regardless of all the publicity both for and against the establishment of Kalkriese as the lost battle site, Professor Schluter's team went into overdrive in their work in the field on the edge of the knoll. As a prolific mass of artefacts continued to be recovered from the main dig area, extra staff was drafted in, including in June of that year another archaeologist, Dr Susanne Wilbers-Rost.

A huge pioneers axe was recovered, and many bronze pieces, both small and large. Some were from Roman uniform fittings. They were carefully picked out of the soil bed, using a combination of heavy tractor shovel scrapes to take the soil layers down inch by inch and Fisher detectors deployed at each scrape stage to ensure even the smallest metal piece was recovered. Major Clunn had convinced Professor Schluter that the Fisher detectors he used, both the 1265's and later 1266's, including the Gemini models were an invaluable asset to both the excavations and the field work. In view of Major Clunn's success with these instruments, Professor Schluter had asked to buy some for the team. Within a few days the team were armed with new specialist equipment.

On Kalkriese in the spring of 1990, a few months after the mask and other important artefacts had been recovered; the archaeological team had nearly completed a full survey of the excavations showing the earthen wall, which straddled the northern contours of the hill. Combined with the nature of the objects and their age, established by use of dating techniques, the site had all the requirements to support the premise that a battle between Roman ad German forces had taken place during the period theVarus legions and disappeared in the German forests.

Soon after her appointment Dr Wilbers-Rost reported to Professor Schluter that in her estimation there could be no doubt that an earthen wall had been erected through the cut of the hill, which at the most eastern edge had been supported by a serial of timber posts, their remains shown as post holes in the sand base of the excavations. That linked to my own theories of the general layout of the site, confirmed that it had all the landmarks of a very effective ambush position. But was this whereVarus had lost three legions and all his support troops and echelons, some 20,000 men? I thought most likely not.

The area was far too small to squeeze that number of men through. Most likely the site was the final, and devastating part of the whole battle that had taken place during the day or days leading up to Kalkriese.

Major Clunn had already made many forays into the highlands to the south-east during 1988 and 1989, but, in April of 1990 he began a series of intensive surveys which took him to over sixty different find sites throughout the highlands laying between the River Lippe and the Weser to the east and north east of it. Nearly all of these finds Dr Berger had written up sites from older records, and it was his reference documents and books that were proving invaluable in the officer's research work. He concentrated his efforts on the two highland wooded features to the north of the Lippe. One, and by far the most important, called the Teutoburger Wald, (Wald - forested highlands) running north-west up to Osnabruck and on to the Kalkriese Berg, and other called the Wiehengebirge (Ridge), running eastwards from Minden and the River Weser, also to join up with the northern edge of the Kalkriese Berg.

Major Clunn now believed the site of the battle had indeed been north of the River Lippe, ad east of the River Ems in the highland feature known now as the Teutoburger Wald; professor Schluter was later to highlight that the former "Osning" (mentioned in old literature), is the Teutoburger Wald as it is know today.

This "Wald", or ridge, runs up from the lands directly to the north of the Lippe, due northwest and then curving away to the underbelly of Osnabruck. Here it becomes a scattering of hills then falling away further to the north, Kalkriese being the northern extremity. Beyond that were the large wet moorlands of the Dieven Wiesen, (Moorland Basin). Historians believed the Roman route to run from the RiverWeser in the central plains across to the River Ems in the east and to cut across this northern most point of the juncture of the Wiehengebirge and the Teutoburger Wald. But did it? The officer thought not, and for a variety of good reasons. His reasoning in support of Kalkriese as the site of the Varusschlacht was that the Legions had come up from the Teutoburger Wald, from their original route leading to the Lippe, and, lured on by Arminius, had changed direction to move north-west up towards Kalkriese.

His belief was that the Legions were cut to pieces by a series of guerrilla skirmishes from the flanks and rear by the German tribes as they moved up through the Teutoburger Highlands their final end at the Kalkriese gap.

By the late Spring of 1990 the full extent of the archaeological digs in Kalkriese was enormous and laid bare for all to see. The digs had come well out of the woodline from the knoll and were moving inexorably across the open field. There were now 200 x 200 yards of excavations, two metres deep in the main, and continuing cuts were being made as the archaeologists pursued the discovery of the Battle of the Teutoburger Wald.

In April 1990, three years after his arrival in Osnabruck and the start of his involvement with Kalkriese, Major Clunn established a link with a Professor Schoppe from the Institute of Hamburg, also a keen amateur Roman historian interested in theVarus project. He had links with the German Luftwaffe and offered his assistance to secure some aerial photographs. The aim was to carry out a series of such photographs of the complete region, including the first main pass areas 10 kilometres due east of Kalkriese. The overflights began during the early summer when Major Clunn began other extensive recces of the highlands of the Teutoburger Wald. After the overflights, the resulting large photographs were handed to Professor Schluter to be examined over the coming months.

Professor Schoppe and the British Officer continued to pursue their photographic interests up until the end of that year, by which time more and more information was being gleaned from the dig site and surrounding areas.

During the following years, much work was done, with a series of large excavations made across the main central area of the battlefield. Many wonderful and impressive finds were made, some indicating the absolute certainty that this place was undoubtedly the site of the last vestiges of the Varus Battle.

In 1994, an amazing discovery hit the headlines. In excavations on the eastern side of the `Oberesche Field' (the central site), a large concentration of bones was discovered. The strange part about this concentration (later dated to approximately 2000 years of age), had been placed in the ground, not thrown or fallen down. Human bones had been interred, a form of spacing, possibly earth or grass sods, and then some horses bones. A mass grave had been found.

It had always intrigued Prof Schluter and the team that no bones or human remains had been found across the length and breadth of the forgoing excavations. The belief was that the chemical content of the subsoil in the area was such that human bones did not survive the 2000 yeas since the battle. However, here was a large accumulation laid out much in the form of a graveyard! This was not as much a surprise to Major Clunn who had previously surmised in discussions with Prof Schluter that the German earthen wall ramparts on the eastern side of the Oberesche Field would most likely have borne the brunt of the mass of Romans pouring into the ambush site as the Germans carried out their devastating attacks on the concentrated mass of Legionaries. Many hundreds of Romans would have been slaughtered in this area as the `Pass' between Berg and Moor became ever narrower.

But it was Tacitus who had recorded his description of Germanicus' visit to the Battlefield in AD 15, and "where he had gathered all the remains together and made a grave for all their fallen comrade" that created a sense of unimaginable excitement for Prof Schluter and his team. This was undoubtedly part of the concentration of human remains that Tacitus had referred to. Two historical events from two different dates circa the time of Christ in the same archaeological excavation area was a staggering revelation. Historical dating and proof of site activity is something all archaeologists seek, but do not always find. To reveal two in one place was a revelation.

Since the, Kalkriese and the ongoing work continues to amaze with its bountiful amount of artefacts, now well in excess of 4,000 finds, and still growing. From 1993 to date Major Clunn continued to seek the outer peripheries of the scope of the battle, particularly interested in the route taken by the Romans when approaching from the east/south-east. Subsequently, by a series of surveys made well outside Kalkriese, he made a number of further finds some 9 kilometres to the south east, in the vicinity of the main passes at Ostercappeln, and Felsen Field. He believes this area to be the actual site of Varus' last battle lager where it was reported by Tacitus that Varus had committed suicide, the remnants of the Roman army possibly breaking out to their final demise at Kalkriese. He also made other finds some 3 kilometres to the west, after which there were no more traces. Here, the last Legionaries had finally fallen to the German tribesmen.

In 1996 a further series of exciting finds in and around the Kalkriese Battlefield. were made. Besides locating many further coin accumulations, recovery was made of one of the most impressive artefacts of the whole twelve years since Major Clunn's first finds. It was the silver remains of a high ranking officers sword scabbard, one of the cross stays bearing an embossed figure of a Roman lady studying herself in a hand mirror.

With the finds of the Mask, the large Pioneers Axe, many pieces and heads of weapons, the sword scabbard pieces, many Varus stamped coins, bronze shoulder clasps inscribed with the name of a Legionary serving in the 1st Cohort of Fabricius, and no coins younger than that of AD9, and much more, Kalkriese is now firmly established as the true site of the last part of the Varus Battle. What is truly amazing about this momentous discovery is that which the archaeological team recover is only that which was not found and plundered by the victorious German tribesmen after the battle, nor found by the Kalkriese farming community during the 1700 - 1900's. And yet, no more than a minor percentage of the whole area has been fully excavated. The tireless efforts of the on-site surveyor, Klaus Fehrs, surveying field by field across the length and breadth of Kalkriese, and Major Clunn's ongoing activities on the approach routes to the central site continue to produce numerous positive results, but essentially there remains so much work to do, so many fields to search, so many excavations to dig, and many years of surveys and fieldwork yet to be done.

In June 2000 the central site became a Battlefield Museum's Park, of walks and pavilions, of graves and quiet places, and most importantly, a monument to victory and defeat, to passion and bloodlust, to trial and tribulation, and to the first and greatest influence on Northern European history from the times of the Romans and the early Germanic tribes. An onsite museum is' also being established, not only to show all the Roman artefacts found, but will portray many other eras of history found throughout the Kalkriese area, from Stone Age, Bronze, Iron and Dark Ages, leading up to the Middle ages to modern times. A 40-metre observation tower is also being erected.

Prof Dr Schluter is now the Resident Archaeologist for the County of Osnabruck, Major Clunn now lives on the battlefield next to the Felsen Field at Ostercappeln, and continues his investigations and surveys seeking the Roman route in to the battle. The archaeological team, led by the site archaeologists Dr Harnecker and Dr Wilbers-Rost have their own agenda for at least the next ten years. Dr Georgia Franzius, on the team from the very beginning as the resident specialist for Roman artefacts has a life times work ahead of herThe search for the truth goes on, and will for many years to come.

(As this was being written, yet another large accumulation of human remains has been uncovered in the central area of the main battle site, including a complete skull, and the cleanly severed half of a man's skull ...cleaved down the middle).

"Varus, Varus, give me back my Legions!" cried Augustus Caesar when he heard of the loss of the Varus Legions.

The Varus Battle In Quest of the Lost Roman Legions

- Background and Battle

Modern Research

Map (slow: 173K)

Jumbo Map (extremely slow: 435K)

More Artifact Photos (slow: 189K)

Back to Battlefields Vol. 2 Issue 1 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com