[Something a little bit different with this one: our battlefield is in coastal waters rather than on dry land and the participants are ships of the Royal Navy and a hijacked ironclad! What prompted me to include it was a recent game of ACW riverine warfare that Southend (late Shoeburyness) Wargames Club members thoroughly enjoyed. Peter's offering also allows the participants a touch of role-playing - Ed.]

At right: The painting "Shah and Huascar" by Ian Marshall. HMS Shah firing while HMS Amethyst, (back), approaches in an attempt to cut off the Huascar.

At right: The painting "Shah and Huascar" by Ian Marshall. HMS Shah firing while HMS Amethyst, (back), approaches in an attempt to cut off the Huascar.

On 6 May 1877 two Peruvian Navy lieutenants were persuaded by exPresident Nicolas de Peirola to mutiny. Together they seized the Peruvian turret ship the Huascar and embarked on a piratical cruise intended to embarrass and topple the Peruvian government. She patrolled the coastline, demanding tolls and goods from the ports and merchant ships encountered.

News of her movements was difficult to obtain as recent earthquakes had damaged the telegraph cables along the coast. Even had they known more, the Peruvian government would still have been reluctant to intervene as the Huascar was the most powerful ship in their navy. It requested that Peru's neighbours should hold the Huascar if she visited their ports for coal or other supplies, while slowly preparing a squadron to put to sea.

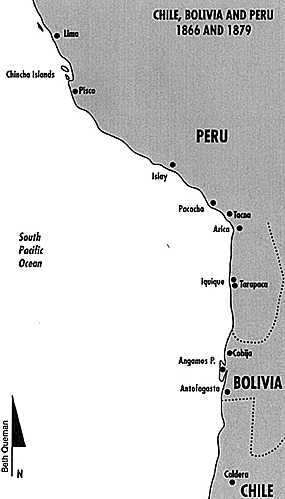

Jumbo Map of Chile, Bolivia, and Peru 1866/79 (62K)

Jumbo Map of Chile, Bolivia, and Peru 1866/79 (62K)

The British C-in-C of the Pacific Station, Rear Admiral Algernon Frederick Rous de Horsey, learnt of this rebellion on the following day, but was content to comment and watch until he received reports of Britishowned ships being held and delayed against their will. Out of touch with the Admiralty, he had to use his initiative. He placed copies of a letter to the Huascar on merchant ships that were possible prey, warning the rebels that he would not tolerate further interference with British shipping.

A bullish reply was received. De Horsey was exhorted to remain neutral, with the rebels claiming that they had not transgressed international law, but also warning that they would defend themselves vigorously, if necessary.

The Huascar's continuing operations, plus a plea from the British Charge d'Affairs in Lima reporting a fear that the Huascar may endanger British operty there, forced de Horsey into action. Thus, the only two Royal Navy ships in the area - unarmoured cruising ships - were tasked to end her career.

The twenty years after the launch of the first true ironclad warship, in 1860, was a period of considerable change in most navies. Ships were being made of iron, many of them armoured with several sheets of inch thick metal backed by up to two feet of teak. To counter this, there was also a revolution in armament. Smoothbore guns firing solid shot or spherical shell were being phased out in favour of rifled guns firing conically-ended cylindrical projectiles. Some were still muzzle-loaded, though the more adventurous nations were installing breech-loading guns.

Most ships were still masted, with the dirty steam engines reluctantly being used by captains to supplement or replace wind power. Thus battle tactics had become new and unfamiliar to a generation which looked to the Napoleonic Wars for its inspiration, and the Royal Navy's last experience of a fleet engagement. Guns were now capable of far longer ranges, though armoured ships were almost invulnerable to them. Now all warships were able to manoeuvre as they liked, no longer having to depend upon the wind.

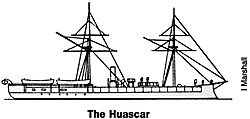

The Huascar was one of these

new ships - a small coast defence

monitor. This type was modelled on

the eponymous vessel of the

American Civil War, the design having

been adapted by European nations for

sea-going operation. They were made

more seaworthy by the addition of breastworks

which increased the freeboard when

cruising, but could be lowered to

operate the guns in battle. Fitted with

two masts, the Huascar had been

built in Scotland and was equipped

with the latest Armstrong guns. Her

machinery and magazines were

behind a 4sqinch iron belt and she

could steam at over twelve knots. Two

ten-inch muzzle-loading rifled (MLR)

guns fired 300 pound shells and were

protected by up to eight inches of iron

in the turret. Muzzle-loading rifled

guns, despite being powerful,

obviously had a slow rate of fire. No

longer could the smooth-bore's

windage and wadding be tolerated,

which had permitted a relatively rapid

reloading. The heavy cylindrical

projectile had studs, required to

engage the thread in the barrel. A

crane was sometimes needed to lift

the shell to the muzzle where it then

was pushed, spiralling down the

rifling, to the base.

The Huascar was one of these

new ships - a small coast defence

monitor. This type was modelled on

the eponymous vessel of the

American Civil War, the design having

been adapted by European nations for

sea-going operation. They were made

more seaworthy by the addition of breastworks

which increased the freeboard when

cruising, but could be lowered to

operate the guns in battle. Fitted with

two masts, the Huascar had been

built in Scotland and was equipped

with the latest Armstrong guns. Her

machinery and magazines were

behind a 4sqinch iron belt and she

could steam at over twelve knots. Two

ten-inch muzzle-loading rifled (MLR)

guns fired 300 pound shells and were

protected by up to eight inches of iron

in the turret. Muzzle-loading rifled

guns, despite being powerful,

obviously had a slow rate of fire. No

longer could the smooth-bore's

windage and wadding be tolerated,

which had permitted a relatively rapid

reloading. The heavy cylindrical

projectile had studs, required to

engage the thread in the barrel. A

crane was sometimes needed to lift

the shell to the muzzle where it then

was pushed, spiralling down the

rifling, to the base.

The British commander, Rear- Admiral de Horsey, with his two unarmoured ships, would have to exploit the enemy's slow rate of fire if he was to avoid having his ships destroyed.

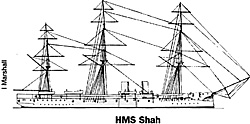

His flagship, the frigate

HMS Shah, was a sister to HMS

Inconstant, the fastest warship then

afloat. Iron-hulled and ship-rigged,

she could manage over thirteen knots

under sail alone, and up to sixteen

knots when steam driven. Her

armament consisted of two 9-inch

MLRs (250 pound shell), fourteen 7-

inch MILRs (112-pounders) and eight

64-pounder MLRs. Under trial

conditions, the 9-inch gun had

penetrated 9sq inches of armour at

1000 yards range, and the 7-inch had

penetrated 7sq inches.

His flagship, the frigate

HMS Shah, was a sister to HMS

Inconstant, the fastest warship then

afloat. Iron-hulled and ship-rigged,

she could manage over thirteen knots

under sail alone, and up to sixteen

knots when steam driven. Her

armament consisted of two 9-inch

MLRs (250 pound shell), fourteen 7-

inch MILRs (112-pounders) and eight

64-pounder MLRs. Under trial

conditions, the 9-inch gun had

penetrated 9sq inches of armour at

1000 yards range, and the 7-inch had

penetrated 7sq inches.

The smaller Amethyst was commanded by Captain Chatfield (father of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Ernie Chatfield, Beatty's Flag Captain at Jutland) and armed with six 64 pdr MLRs on each broadside. She was capable of one knot faster than the Huascar, under steam or sail. Full details of the three ships are given in table 1.

At first sight, a comparison of the ships may indicate a very unequal competition in favour of the Royal Navy, but previous experience of action between armoured and unarmoured ships showed the opposite. Even when armoured ships had been unable to fire, they had been able to resort to their ram bow, which would cut through a lighter ship with little damage to the ironclad.

Coastal or river actions in the American Civil War had shown that armour was often impenetrable and ramming or mines could decide an action. The Battle of Lissa, between Italian and AustroHungarian fleets in 1866, misleadingly re-inforced the importance of the ram. (There followed a generation of ships designed with ram bows and as many forward- bearing guns as possible. The need for these vessels was quickly superseded, however, by breech loading guns which were able to penetrate armour at battle ranges.)

The main advantage that the British had was their superior speed and training. The speed would allow them to choose the range of engagement, but this in itself was a dilemma. If they were too close they would risk being rammed, but only at short ranges could they hope to hit and penetrate the armour of this very low freeboard target. At longer ranges, the turret ship would score fewer hits, but their own hits would merely bounce off it.

In the action itself, the two British ships separated and the Huascar fired at each in turn. Owing to the slow rate of fire, each British ship could expect to be shot at by only about ten 10" projectiles each hour, but any one of them could cause immense damage. In return, their combined broadsides greatly outnumbered the rebels', but each shot was unlikely to penetrate her armour.

THE ACTION

The British found the Huascar on May 29, near Ylo, and Admiral de Horsey demanded her surrender. He sent a letter stating that he had 'come to take possession of that ship in the name of Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain', adding mention of 'the Shah's undoubted

superiority of force, and her high speed.'

The British found the Huascar on May 29, near Ylo, and Admiral de Horsey demanded her surrender. He sent a letter stating that he had 'come to take possession of that ship in the name of Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain', adding mention of 'the Shah's undoubted

superiority of force, and her high speed.'

The Huascar refused to surrender, and fire was opened at 3:06 pm when the range was about 1,900 yards. The Huascar's first two rounds were one ten-inch shell and one 40-pounder. The former passed just behind the Shah's foretop and the latter behind the mainmast, cutting away royal and topgallant yard ropes. Whenever possible, though, the unprotected 40-pounder guns were made unusable by the fire from the Shah's machine guns and the Amethyst's marines.

The Huascar, both de Horsey and Chatfield report, was 'beautifully handled'. She tried several ruses, some times turning to ram, though the superior speed of the British kept them safe, and at other times making for shallow coastal waters, both to entice the British ships to run themselves aground, and to prevent them from firing in case they hit the town behind.

The Huascar, both de Horsey and Chatfield report, was 'beautifully handled'. She tried several ruses, some times turning to ram, though the superior speed of the British kept them safe, and at other times making for shallow coastal waters, both to entice the British ships to run themselves aground, and to prevent them from firing in case they hit the town behind.

At times this succeeded as both ships had to cease fire for fear of damaging civilian property, and Patrick Riley, an Able Seaman on the Amethyst remembers: 'During the afternoon, a crowd of Peruvians mounted on horse-back were watching the fight from the top of some hills to the right of the town...

The Shah then fired a broadside from her port guns, but the shells passed over the Huascar and struck the water midway between her and the shore, ricocheting up the hillside, and throwing up clouds of earth. It was very amusing to see the way those horsemen scattered in all directions to take cover!'

After about two hours of inconclusive action, mainly between the Huascar and the Shah, the turret ship tried again to ram, and the Shah launched the first ever Whitehead torpedo used in action. The Captain's log reports: 'At 5.35 after receiving the fire from Huascar's turret, closed to 400 yds and fired a broadside and Whitehead torpedo - Torpedo missed Huascar, increased distance to 2000 yds.' In those days, the torpedo would have been slower than her target, therefore despite the close range, it could be out-manoeuvred if the target was aware of the launch.

The action ended when the Huascar got so close to the town, and the merchant shipping there, that the Shah was unable to fire. That night the Shah despatched a steam launch, equipped with both spar and Whitehead (or 'fish') torpedoes, looking for the Huascar among the merchant ships at anchor, but the Huascar had steamed away in the dark and on the next day she surrendered to the Peruvian government.

Neither of the British ships was hit though despite his threats to the Huascar, de Horsey was under no illusions as to the danger of the action. Afterwards he wrote to the Admiralty: 'Had the 300 pounder shell which cut away the main sail tackle struck the mainmast of the "Shah", its explosion would probably have brought the iron mast down at great risk of disabling the engines through the engine room skylight immediately abaft it. - Had the shell which passed close, almost touching, under the Shah's counter struck her rudder - Had the "Huascar" succeeded in her attempts to ram the "Shah", and more especially entice her into shallow water at high speed. Had only a hot bearing necessitated stopping, their Lordships will readily appreciate that the result might have been very different.'

He followed this with comments about the poor layout of the guns on his ship, such that only one 9-inch could ever bear on the target at any one time, and seemed to have become a convert to the use of turrets.

The Huascar had been struck sixty times, with one 9-inch shell penetrating her armoured belt at a point where it was 3sq inches thick. This did not affect her performance despite killing one and wounding three others. The funnel casing and funnel had been struck about twelve times, and the turret hit once, by a 7-inch shell penetrating three inches. Riley later visited the ship and reported: 'The mast and funnels were riddled with shot, the funnel casing, engine hatches, and everything above decks being shattered to pieces. The turret was marked all over where shells had struck it, but there was no part where one had penetrated through it, neither had any projectile gone through the armoured sides of the ship. It was found, on going below, that several fragments of shell had worked their way down between the deck and the turret, thereby jamming it and preventing it from revolving.'

It appears likely that Chatfield's plan for boarding her would have led to disaster, as provision had been made for spraying boiling water onto any boarders, and the hatches had been covered by two inch thick iron plates.

The first England was to hear of the action, or even of the rebellion, was in a telegram from Lima received six days later which read 'British Admiral has attacked rebel ironclad. That vessel afterward capitulated to Peruvian squadron. Great excitement here.'

More IronClad Pirate

-

Ironclad Pirate Huascar: Historical Overview

Ironclad Pirate Huascar: Ship Specifications

Ironclad Pirate Huascar: Wargaming the Battle

Ironclad Pirate Huascar: Preserved Ship in Chile

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 7 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com