Another "what-if' battle from the Peninsular War but, this time, taking an actual small-scale combat and looking at what might have occurred if the rearguard action by Lord Paget had been the full-scale field battle which Sir John Moore considered seriously at the time. Caught in the depths of a fierce winter in one of Spain's most inaccessible regions, the British were itching for the fight which would have restored their disintegrating morale but would have risked their very existence, their commander's reputation and the whole outcome of the War...

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Spanish Armies were defeated and scattered; Madrid was in the hands of Napoleon and Sir John Moore's small expeditionary force found itself effectively alone and isolated - how had this occurred?With high hopes, the British had set out to lend support and military assistance to their new allies. Refused entry into Spain, they had acted to oust Marshal Junot from Portugal under the able command of Sir Arthur Wellesley. The brilliantly successful campaign had been marred by the infamous Convention of Cintra which allowed Junot's army to return to France with much of its booty and the facility to return later and to fight again - which, indeed, it did.

Wellesley had returned home to clear his name and Sir John Moore was appointed to the command of his country's only field army. On arrival in Portugal, on 9th October 1808, Sir John discovered that there was transport facility; the distribution of the troops to mount an expedition into Spain, which he had requested, had not been undertaken and there was little, if any, mapping or even surveying of the roads over which he would need to march. The delays which these neglects engendered went a considerable way to placing Sir John in the dilemma in which he found himself soon after his expedition set out, between 11th and 26th October.

Having entered Spain along three separate roads, with his artillery and cavalry separated unnecessarily from his main force as a result of the poor reconnaissance, he learned, on 22nd November, that the Spanish armies of Blake and Belvedere had been defeated in the battles of Espinosa and Gamonal.

Since his orders were to cooperate with these armies and that of Castanos, for the purpose of halting Napoleon's march to Madrid, he faced a daunting prospect. Castanos did not, in Moore's opinion, stand much chance of halting the Emperor on his own; Moore could not sensibly continue his march until his artillery and cavalry caught up and the 12,000 British reinforcements he was expecting had been refused permission to enter Spain by the Galician Junta. They were, in fact, held up in La Coruna harbour for almost a fortnight and, by 22nd, had been on the march for 18 days.

Then came the news that almost resolved Moore's dilemma on what he could do.

The rout of Castanos' Army of the Centre at Tudela meant that there was not a single, effective Spanish Army with which Moore might cooperate. Worse, French cavalry had been sighted at Valladolid and Napoleon must soon be at the gates of Madrid. Retreat to Lisbon seemed the only sensible option. The Spaniards, however, were desperate: the British force was the only serious opposition which might be mounted. It would, undoubtedly, be crushed but the Central Junta implored the British general to march to the capital. Once again, Moore was faced with a dilemma.

Should he risk the march on Madrid, which would lead to certain destruction but would at least preserve some reputation for Britain in the eyes of their ally, or should I preserve his precious army and make for the coast?

He determined on the latter course and sent instructions to Sir David Baird, commanding the reinforcements, to retire on La Coruna whilst he, himself, now with his own force concentrated around Salamanca, would return to Lisbon whither Baird might sail to join him. Suddenly, a glint of sunlight penetrated the gloom: the French cavalry at Valladolid appeared ignorant of Moore's very existence! They made no attempt to approach Salamanca and moved away to the south.

At last, the British general could think seriously about making a contribution to the struggle. Rescinding the retirement order to Baird, Sir John determined to attempt to cut French communications by a movement on Valladolid or Burgos, thereby distracting their attention from Madrid and giving the Spaniards much needed time to re-group.

On 30th November, a despatch from the Marques de La Romana, the Spanish general who had commanded the contingent Napoleon sent to Denmark - whilst subverting Spain's government and who had returned to Spain with several of his battalions, advised that he had succeeded Gen. Blake and that his now rallied men would cooperate with the British. By 10th December, the preparations had been made; the sick (about 4,000) and the baggage were sent back to Lisbon. On 11th, the army marched and the divisions of Gen. Edward Paget and Gen. Fraser achieved a junction with Baird's cavalry, under Lord Henry Paget, at Toro.

It was at this point that Moore learned of the fall of Madrid. It might have been expected to throw him back into his earlier mood to "...give the thing up. "1 but, having made the decision to act aggressively, Moore held to his plan. He had learned that La Romana had some 20,000 men but only 7,000 or 8,000 were properly clothed and armed; however, the Spaniard would cooperate with Baird on the British left flank with these troops.

On 21st December, the 10th and 15th Hussars attacked a French cavalry detachment of Chasseurs and Dragoons at Sahagun. The latter British unit destroyed the former French one and this caused the Dragoons to rout.

They fell back on the main body of Marshal Soult's Corps, thus warning him of the presence of Moore's army. Once the French became aware of the British force, Napoleon immediately ordered their destruction and sent the Corps of both Soult and Ney, supported by Junot (who had, by now returned to Spain) to carry out the task. He intended to join them with part of Victor's Corps, some of the Reserve at Madrid, much of the Cavalry Reserve and the Imperial Guard. Thus' some 80,000 men were diverted from consolidating the conquest of Spain to deal with a British army of around 25,000.

At first, the Emperor could gain little intelligence of Moore's whereabouts and the British general, much to the incredulity of his troops, commenced a hurried retreat towards the Galician coast, gaining a considerable lead over his pursuers. It had been his intention to surprise and defeat Soult but, once news of the other French movements against him was received, he lost no time in making himself scarce.

The British retreat to La Coruna bears passing resemblance to that of the French Grande Armee from Russia in 1812; the weather was atrocious, the terrain rugged in the extreme and the pursuit dogged. However, the numbers involved were much smaller and the casualty rates far lower. Nonetheless, for both pursuer and pursued, it was a nightmare.

Once the French discovered what had happened, the pursuit was engaged in earnest. Some remarkable small actions between the British rearguard and the French advanced guard (many cavalry vs. cavalry actions) were fought - almost always to the ultimate British advantage - and both sides showed skill and bravery in their efforts. Craufurd's Light Brigade and Gen. Edward Paget's Reserve Division were frequently involved and, thanks to them, the main body successfully eluded the French. This threw the pursuers on to the road taken by La Romana's force and the Spanish were caught and defeated at the Bridge of Mansilla.

Eventually, with Moore having eluded him for the rest of December, Napoleon left the pursuit to his subordinates, Ney and Souit and, with his Guard, returned to France. The retreat had severely affected the morale of the British army. Those units engaged in rearguard actions were still well disciplined and in good spirits but those not so engaged fell to drunkenness, rape and murder at every town and village. Not all the units misbehaved but there were all too many who did. It was clear that, for these troops, the only solution was to fight.

Moore considered standing at various places - he had indicated to La Romana that he would do so at Astorga, for example but he abandoned the idea quite quickly. After detaching Craufurd's and Alten's Flank Brigades to march towards Vigo, he considered both Bembibre and Villafranca but was fearful of being out-flanked. Also, at both these places, awful scenes of drunkenness and indiscipline occurred; inebriated soldiers, frost-bitten women camp-followers and pathetic infants strewed the villages and roads between the two towns. Eventually, Moore was forced to take draconian measures against the troops as punishment. During these regrettable scenes, the rearguard reached the town of Cacabellos which presented one of the most formidable defensive positions on the route to the coast.

Moore, by now being quite set on the retreat had not seriously considered offering battle with his entire army at Cacabellos, despite the excellence of the position. Edward Paget's reserve division, had taken over rearguard duties from Lord Henry Paget's cavalry, the terrain being unsuitable for the mounted arm, and it was to them that the action at Cacabellos fell.

TERRAIN

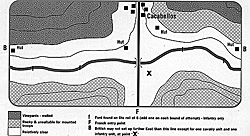

A bridge carrying the high road from Madrid to La Coruna crosses the winding River Cua which runs roughly north/south just below the town of Cacabellos. On the west side of the river are vineyards which run parallel to the river and are bordered by stone walls . The road on the East side of the river forms something of a defile and, once the bridge is crossed, it rises fairly steeply towards the town, flanked on either side, by the vineyard walls. The land is very rocky on the west side and highly unsuitable for cavalry. The river may not be crossed easily except by the bridge, although it is fordable at various points by infantry.

Larger map - very slow (84K)

Jumbo map - very slow (286K)

COMBAT OF CACABELLOS

The historical action took place between, on the British side, the five battalions of the Reserve division and the 15th Hussars plus one RHA battery of six guns and, on the French side, Colbert's cavalry brigade, Lahoussaye's dragoon division and, later, Merle's infantry division. It would form an interesting "one night" wargame and so a brief description follows:Paget deployed one Hussar squadron and two companies of 1/95th Rifles on the West side of the bridge to observe the enemy approach. The rest of the 15th Hussars were withdrawn to the other side of the river, where the artillery battery, supported by 1/28th Foot was deployed across the road, covering the bridge. The other battalions of the Reserve division were hidden in the vineyards, protected by the walls.

Gen. de Brigade Colbert, commanding Ney's Corps cavalry (15e Chasseurs a Cheval and 3e Hussards), charged the British cavalry squadron who beat a hasty retreat across the bridge, disordering the two rifle companies who had not had time to cross. The French cavalry captured 48 riflemen and halted before crossing whilst their commander assessed the situation before him. Seeing only the artillery and its supporting infantry battalion and making no attempt at further reconnaissance, the handsome and dashing young brigadier formed one of his two regiments across the road in four files and resolved to carry the bridge in a famous and furious charge. In this, he was completely and utterly foiled as projectiles from the guns of the horse battery ripped through his leading ranks. Disordered but still in motion, the French cavalry moved towards the 28th. Suddenly, from either side of the road, fire from 95th and 52nd belched forth and the horsemen turned and pelted for the bridge, leaving many prone figures behind them, including the brave but foolhardy Colbert, a bullet from Rifleman Tom Plunkett's Baker having passed through his skull.

Lahoussaye's dragoons arrived shortly after and, fording the river in a number of places on foot, bickered with the men of the 52nd. They were no match for the infantry in a small arms contest and it was not until Merle's voltigeurs could be brought against the Reserve division that they gave any ground. Whenever a formed column of infantry attempted cross the bridge the horse artillery caused numerous casualties and the attempts were given up. It was only after nightfall that the Reserve division retreated through the town in good order, covered by their cavalry.

Although the losses were about even - 200 on each side - the Reserve division achieved the objective of allowing Moore time to destroy surplus provisions in Villafranca before the army marched out.

WHAT IF...?

The postulation for this article is that Moore decided to fight at Cacabellos with his entire army and achieve a victory over his pursuers. One of the problems is to decide what might constitute or result from a victory. But more of that later.The only information we lack is the details of what troops could have fought and some idea of the characters and abilities of the generals who might have been involved.

WARGAMING CACABELLOS

NOTE: For the purposes of this article, a figure is considered equivalent to 50 men.C.-i.-C. Le Marechal "Nicolas" Jean-de-Dieu Soult, The first consideration when deciding how to play a wargame of this scenario is what Moore would have achieved by fighting a field battle. He has been criticised for failing to make stands at various places and, indeed, when he did offer battle at Lugo, Soult refused to fight, waiting for Ney and the reinforcements to come up. Obviously, Moore did not wait to be outnumbered. Moore could not afford a defeat. He commanded Britain's only field army and was under strict instructions not to allow its destruction. If he had tempted Soult to battle and beaten him, what then?

His best hope was a sufficiently comprehensive victory to send Soult back on his supports (Ney and the two Vlil Corps divisions) and give himself adequate time to quit Spain for England. He achieved exactly this two weeks later at La Coruna, although Soult was not routed and remained in position. He certainly could not take the offensive after a victory being so heavily out-numbered.

Consequently, the situation must be looked at almost as a campaign scenario covering the three days it would take the reinforcements to reach Soult's Corps, i.e. January 3rd to 5th. This will certainly mean a game spread over more than one session. My suggestion is to allow the British to set up the Reserve division and one cavalry regiment, actually placing only those forces on the table which the French could realistically have seen from their arrival point just East of the bridge and get the battle under way with French troops having pre-written an order of march (Colbert's cavalry in the van). Hidden units are only revealed when an enemy would become aware of them (sighting or receiving fire).

The first "day" of the battle should be telescoped into a relatively small number of bounds (ten, perhaps) representing the lulls in fighting occasioned by reconnaissance and the arrival and deployment of successive French units. This will almost certainly not provide a final result and, from the commencement of "day 2" (bound 11), French reinforcements can start arriving. This is regulated by rolling a 20-sided die, Heudelet's division appearing on the bound equal to 11 plus the die score. Delaborde will arrive a number of bounds later, equal to the score on a 10-sided die. On each bound after no. 30, an ordinary die is rolled and Ney's Corps will appear on the bound after a 6 is rolled.

The British score one point for each bound in which they still have at least one brigade on the table and one point for each unit they exit in good order (you must judge what that means on the basis of the rules you use) from the base line behind Cacabellos. There are 45 British units.

The French reduce the British score by one for every figure casualty and by 5 for every British unit routed. If Soult's Corps suffers more than 25% casualties before any reinforcements arrive, the British win automatically. Otherwise they need 50 pts for a decisive victory, 40 for a tactical victory and 30 for a Pyrrhic victory. Anything else is a disaster!

All this presents both commanders with some knotty problems and gives the British an incentive to remain on the field attempting to amass bound-points whilst risking attrition points losses as they do so. The French must be fairly aggressive to prevent the British from piling up too many points but can not afford to suffer heavy casualties themselves in the earlier stages.

You may find that your rules necessitate an adjustment to the victory levels but this should not be too difficult to manage.

NOTES

1 Moore to Hope - Salamanca 28th November.2 Park, S.J. & Nafziger, G.F. (The British Military, its System & Organisation 1803-1815 Rafm Co. Inc. 1983).

3 There were, in addition to those divisionally allocated, or in the Reserve, five Foot Co.'s "in the Penninsula" (Paul & Nafziger - op cit. pp111-117) at this time: 10th Co., 5th Bn. (E. Wilmot transferred, F. Glubb succeeded); 2nd Co., 4th Bn. (G. Skyring); 6th Co., 7th Bn. (C. Sillery); 7th Co., 8th Bn. (R. Lawson). Drummond's last recorded command was in 1804 with 10th Co., 8th Bn.

4 Oman (op cit, Vol 1p646) & Napier (op cit. Vol 1p624) indicate that he was a Lt. Gen. whilst Lachouque, H., Tranie, J. and Carmigniani J-C. (Napoleon's war in Spain - Arms & Armour Press 1982) say he was a Maj.-Gen.

5 Armed with the Baker Rifle.

6 These are all listed by Park & Nafziger (op cit. pp111-117) as at the battle of La Coruna (Jan. 16th) as opposed to simply present "in the Peninsula". See also footnote 3. Napioer (op cit.) shows 5 "brigades" of foot artillery in the park plus the six which were allocated to divsions but does not give the names of their commanders.

7 I can find no reference which gives me brigade allocations for this time. I have made some (probably unwarranted) assumptions to provide a usable orbat.

8 There is coknsiderable confusion on Oman's (op cit. Vol 1) data on Soult's two divisions. For example, he shows 1st Div on p640 as containing three btns. of 2eLeg. on Nov. '08; on p562 he says that Junot's corps was broken up to supply extra men for Soult & Ney comprising"...many third battalions belonging to regiments already in Spain: they were directed to rejoin their respective head quaters." For La Coruna, in Jan. '09, he still shows (p585 footnote) 1st Div with 3 Bns. of 2eLeg., was "drafted to join its regiment in Merle's Div., 2nd Corps." - this in Dec. '08. A similar but oppisite situation arises for 31e Leg. Our orbat is, therefore something of a compromise.

9 In line with note 8, I have assumed this brigade to be composed of the units from Junot's Corps.

10 I have used brigade commanders' names from the return of VI Corps in Oct. 1809 while Ney was on leave and Marchand commanded. This id obviously speculative in view of the time elasped.

FURTHER READING

Sir Charles Oman,"A History of the Peninsular War"

Greenhill

Sir W.E.P. Napier

" History of the War in the Penninsula"

Constable & Co.

Lachouque, Tranie, Carmiginani

"Napoleaon's War in Spain"

Arms and Armour Press

P.J. Haythornthwaite

"The Napoleonic Sourcebook"

Guild Publishing

Sir Peter Hayman

"SOULT Napoleon's Maligned Marshal"

Arms & Armour Press

Rev. G.N. Wright, M.A.

"Life & Campaigns of Arthur, Duke of Wellington"

Fisher Son & Co.

S.J. Park & G.F. Nafziger

"The British Military - its System and Organisation 1803-1815"

Rafm Co. Inc.

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 6 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com