Headquarters Plan

Headquarters Plan

Before marching out on campaign, an army commander in the early Seventeenth century would decide upon a plan for the deployment of his army for battle. He might discuss the alternatives beforehand with his senior subordinates or he may impose his own preference. Once the decision had been made, a plan would be drawn out on paper by the General or his Sergeant Major General. I would describe this as a "Headquarters Plan".

The Sieur du Praissac described this process in his famous work Discours Militaires, which was largely based on the new Dutch practice, as:

"The Sergeant major Generall receiveth from the Generall a plat of the form which he will give to his Armie, the disposition and placing of the members of it, Cavallrie, Infanterie, Artillerie; the order which they should observe in fight, with commission signed by the Generall to dispose it in that manner.

To this commission the whole Armie must yeeld obedience, and the Sergeant major Generall with the Marshals of the field shall dispose thereof, according to the form and place which the Generall shall have prescribed" (1).

Several copies would be made, sometimes by an engineer officer on the staff. There would be a final discussion and the senior commanders would receive copies of the plan. Officers down to brigade level (brigades of either cavalry or infantry) would receive one personally if they attended the meeting or from the Sergeant Major General if they did not. An army marching where it might meet enemy forces would use an order of march which would enable it to deploy directly into battle formation. In order to achieve this each brigade had to be in the correct order when the army left camp and each brigade commander had to know the correct place for his brigade. The brigade commanders should already have trained their men in various styles of deployment but, ideally, the whole army would also practise their commander's chosen plan or plans before marching out on campaign. The Dutch leader Prince Maurice of Nassau and his successor, Prince Henry, and Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, were noted for carrying out these practise manoeuvres before a campaign. Sometimes practise deployments would be conducted during a campaign.

Commander's Choice

The commander's choice of battle plan would be limited to the range of formations currently in use and, for a commander with experience in Protestant armies, this would be based upon one of four main models. Variations upon these four models would made for a particular campaign and would depend upon the personal preferences of the commander, the ground over which he would fight, the number of troops available, the ratio of cavalry to infantry and the type of training which his own and any allied troops had received.

The leading commanders of the day, and those who admired or sought to emulate them, maintained collections of such plans. Some of these plans were based on examples from the classical past, some were formations previously used by the general himself or by famous contemporaries and others were speculative for experiments or future use.

Prince Maurice of Nassau saw his collection as essential to his military practice and onE of his officer's recorded that the Prince "was wont to say That whosoever wrote not downe the passages of the warres (both his owne and other mens) would never have the honour to Command in chiefe well. To this purpose also, he would show mee many of his owne papers; saying this to mee. It male be you maie think it strange that I keepe such poore papers by mee. To which he often made his owne Answere: That if hee should not have donne so, or should now loose those his papers: He should be to seeke often times. Affirming those withall that a Soldiour might learne by his own errors, as well as by his enemys" This was that he usually called his Experience' (2).

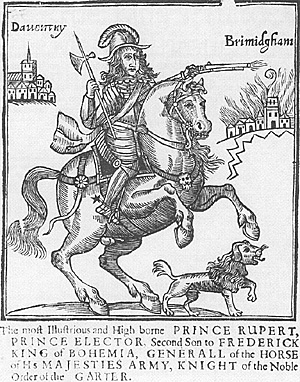

Several of these collections survive but only that of Sir Bernard de Gomme records battle plans used in the English Civil War. This collection contains four plans used by de Gomme's patron, Prince Rupert, for the battles of Edgehill (23 October 1642), Marston Moor (2 July 1644), and Naseby (14 June 1645) and the deployment of the Royalist Army for the relief of Donnington Castle (9 November 1644) (3).

Plans of this type may show the General's original intentions for battle deployment during the campaign or include some modifications to take account of major changes in the army strength such as a large detachment sent away on some special service or a significant allied force joining. The commander may also make some revisions once he had chosen the ground he intended to fight on or received advice from his scouts of the position he would have to attack. Of the four Civil War plans in de Gomme's collection one, Edgehill, shows the plan introduced by Prince Rupert to replace the Earl of Lindsey's original Headquarters Plan for the Royalist Army and another, Marston Moor, shows a plan based on his original Headquarters Plan but with amendments to take account of the junction with the Earl of Newcastle's Northern Army. In any event the plans show the General's intentions and were drawn up before the battle, they were not drawn up afterwards as a record of the battle itself. As such they provide a useful starting point for any study of an actual battle but they must be used with care.

Headquarters Plans also provide a valuable indication of the influences on a particular General's tactical style as they can be compared with similar plans in European collections and contemporary works on military theory and practice. An examination of the four Civil War plans in de Gomme's collection shows that Prince Rupert's tactical style had changed by November 1644 as he became more strongly influenced by styles used in Germany during the 30 Years War. This was the last stage in the development of his battle plans. The plan recorded for November 1644 was not tested because the Parliament armies made no effort to counter the relief of Donnington Castle and essentially the same plan was used for Naseby, some seven months later. The infantry deployment used at Donnington Castle and Naseby is based on a German model rather than Dutch or Swedish and the cavalry deployment is based on the latest German style.

Figure I shows three battle plans, the first is the Imperialist General Albrecht von Wallenstein's "Headquarters Plan" for the campaign which ended in the battle of Lutzen (16 November 1632) (4). This is the best surviving example of a plan actually issued to subordinate Generals and was found on the body of Gottfried Heinrich, Count Pappenheim after the battle; bloodstains obscure the centre of the original and this redrawn version shows the plan as it would have appeared originally.

The key to this plan shows infantry as a plain block and cavalry as a block with vertical lines. This form of notation is found in use in Dutch plans at the turn of the Seventeenth century and was in general use by West European armies by the Thirty Years War; Sergeant Major General Sir James Lumsden's plan of the Parliamentary and Scots armies for the battle of Marston Moor uses the same keys (5). The second and third plans are from de Gomme's collection and illustrate Prince Rupert's plans for the relief of Donnington Castle and the battle of Naseby. De Gomme drew these from the the original battlefield orders and the surviving plans use a colour key for the unit type. The illustations here, by Derek Stone, uses the style of notation which would have been appeared on the original "Headquarters Plans". The infantry deployment in all three plans follows the same basic model.

Figure II shows the right wing of cavalry from all four of Prince Rupert's surviving plans, Edgehill, Marston Moor, Donnington Castle and Naseby. The first two show cavalry formations in the Dutch style which deployed cavalry on a draughts board pattern with the units in the second line facing the intervals in the first, although the second plan (Marston Moor) adds the Swedish innovation of "commanded" sections of musketeers for firepower support. The last two show plans in the latest German style which placed the second line cavalry units directly behind the first and retained the use of "commanded" musketeers. The rationale behind this change was that whereas broken or exhausted infantry formations could retreat straight back by an about turn or simply turning around and running for their lives, cavalry had to wheel and if deployed in a draughts board pattern they would wheel directly into their supporting second line. By drawing up bodies of horse one directly behind the other, this German system reduced the risk of a shattered first line breaking up its own supporting second line (6).

Comparisons

The following points can be drawn from this comparison:

- 1 Prince Rupert's tactical theory continued to develop as a result of his practical experience during the Civil War, reaching its final stage in November 1644.

2 After experiments with Swedish and Dutch styles, Prince Rupert's final battle plans were based on the latest German styles used during the 30 Years War.

3 In their final version the plans show Prince Rupert to be a leading Commander on a European scale, comparable in terms of technical ability with the best of those who had fought in the Thirty Years War.

4 The deployment used at Naseby had been in use by the main Royalist "Oxford Army" for seven months prior to the battle of Naseby, ample time to practise deployment. This counters the popular criticism that these plans are theoretical rather than practical. They are, in fact, as much a part of practical military life in the Seventeenth century as weapons training, mutiny or plundering.

NOTES

(1) Sieur Du Praissac: Discours Militaires (Paris, 1612). This was a very popular, pocket-sized book with at least five French editions and later translations in English and German. The English translation, from which this quote is taken, was translated by John Cruse and published in Cambridge in 1639, p.139. Cockle's Bibliography of Military Works up to 1642 refers to another edition of the English translation published in 1642.

(2) Lord Wimbledon: Demonstration of Divers Parts of War. British Library Royal 18 CXXIII f13/13v. The author, Edward, Lord Wimbledon, had served in the Dutch army under Prince Maurice and his comment here records his personal recollection of discussions with the Dutch leader.

(3) Three of these plans, for Marston Moor, Donnington Castle and Naseby are to be found in the British Library under the references British Library Add MSS 16370 folios 64v/65, 60v/61 and 62v/63. The fourth, Edgehill, is in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle and has been reproduced in Peter Young Edgehill 1642, The Campaign and the Battle (Roundwood Press, 1976). All four of these plans are carefully redrawn versions of the original "Headquarters Plans" and the different units are distinguished by different colours for musketeers. pikemen and cavalry rather than the presence or absence of shading.

(4) Heeresgesichtes Museum, Vienna. Reference: Kat. Erben/John 1903 nr75/3. This is the Headquarters plan for the later stage of the campaign. It could not be used in this form at Lutzen because Gustavus Adolphus attacked the Imperialist army after it had dispersed for winter quarters. Pappenheim's contingent joined the army on the battlefield. However, it does show the state of Wallenstein's tactical theory at the time and his army would have been deployed in a similar style for Lutzen.

(5) Lumsden's plan is reproduced in Peter Young Marston Moor 1644 (Roundwood Press, 1970).

(6) Raimondo Montecuccoli discusses the comparative advantages of this style of cavalry deployment in his Sulle Battaglie - Concerning Battle. This is accessible in an English translation, Thomas Barker The Military Intellectual and Battle, Raimondo Montecuccoli and the Thirty Years War (State University of New York Press, 1975); the section on this style of cavalry formation appears on pp 95/96.

The manuscript Sulle Battaglie is thought to have been written between 1639 and 1642 while its author, then a Cavalry Colonel in Imperial service, was a prisoner of war. It provides a valuable insight into the developing military theory and practice of professional officers serving in the Imperial army. This is the same period that Prince Rupert was a prisoner of the Imperialists and he is likely to have discussed military theory with the Imperial officers who guarded him and, more importantly, those he met at the Imperial court at Vienna prior to his release.

Those with a broader interest in Montecuccoli's career and the later impact of his military thought will find an interesting chapter in A Gat: The Origins of Military Thought from the Enlightenment to Clausewitz (Clarendon Press, Oxford 1989). Both Barker and Gat give detailed references to European articles on Montecuccoli, the most notable being Piero Pieri, "Raimondo Montecuccoli. Teorico delta guerra", Guerre e politica negli scrittori italiani (Milan, 1954).

ECW Battle Plans 17th C. Deployments by Keith Roberts.

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 1 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com