This issue we take a look at one of our oldest military institutions,

the United States Marines. While some may quibble about their place in

the "Guards" section, nobody can say that they are not an elite force,

acting on more than one occasion as "palace guard" in numerous places

around the globe. Last issue, we discussed a nation's military potential

ratio, or the degree to which a country is militarized. Until the Second

World War, our ratio was very low, at times nearly non-existent. We rely

on the concept of the citizen soldier in times of crisis, which is why

today reserves make up such a large portion of wartime strength.

This issue we take a look at one of our oldest military institutions,

the United States Marines. While some may quibble about their place in

the "Guards" section, nobody can say that they are not an elite force,

acting on more than one occasion as "palace guard" in numerous places

around the globe. Last issue, we discussed a nation's military potential

ratio, or the degree to which a country is militarized. Until the Second

World War, our ratio was very low, at times nearly non-existent. We rely

on the concept of the citizen soldier in times of crisis, which is why

today reserves make up such a large portion of wartime strength.

The Marine Corps was formed in 1775, based on the British model of naval infantry able to conduct landings and engage other ships with small arms or boarding. After the Revolution, due to domestic budgetary considerations, they were disbanded, only to be recalled during the Quasi War with France and the war against the Barbary Pirates. Their mission remains essentially unchanged after two hundred twenty years. They provide security in high-risk areas, and support naval operations by providing amphibious forces capable of taking and holding land targets.

Marine forces have participated in every major war and have been the spear point in all minor ones. Famed for rigid discipline and arduous training, the United States Marine is the symbol of bravery, loyalty, and endurance. Their motto, Semper Fidelis, "always faithful" remains the simple summation for a tradition of excellence in the history of this country's military.

For the first time since the fall of Rome, a group of elite troops took an oath of loyalty, not to a sovereign or despot, but to an ideal, a piece of parchment called the Constitution, to uphold the truths found within. As the Marines increased from a handful of men in 1775, to hundreds of thousands during the Second World War, it might seem that their elitism was diluted by conscription and lowered standards. However, true to the nature of Guard-type units, they maintained a higher standard than all other arms, a standard which persists today.

The training scandals of the 1950s were overcome by improvements in the way drill instructors treated recruits; striking recruits and the carrying of swagger sticks were frowned upon. Morale rose from post-Korea lows until by the time of the deployment to Vietnam, the Marines were once more a confident fighting force.

The mission of the Marines in Vietnam was an extension of their past missions. At the beginning of US involvement of ground forces in Indochina, the Marines were just emerging from a tumultuous period of reorganization following the Korean War. Lessons learned in the freezing cold of the Korean peninsula were being added to the experiences in the jungles of the Pacific during World War II.

The end of the Korean War saw a slow erosion of Marine Corps manpower, falling from 248,000 in 1953 to 170, 621 by 1960. Congress and President Eisenhower constantly battled over the Marine Corps budget. There were a few bright spots, however. The Commandant of the Marine Corps was elevated to a separate seat on the joint Chiefs of Staff, and aggressive planning managed to keep the ratio of fighting troops to support troops extremely high, so that budget experts could see that the Corps remained an aggressive, trim force.

Cold War

The Cold War and the increasing sizes of Communist armies prompted planners to add more tactical nuclear weapons to Marine units in an effort to give the appearance of "more bang for the buck" after manpower cuts. However, Marine missions had nothing to do with the possible nuclear battlefields of Europe. They continued to act as quick strike forces in the Caribbean, and remained ready to help civilian and political elements from Lebanon to Central America.

During this interwar period, experiences helped to prepare Marine units to fight future wars. Marine Corps leaders were among the most visionary thinkers in the military establishment, which always meant an increased war fighting capacity over foes. The M-1 Garand of WWII and Korea was replaced by the M-14. While the M-14 used the standard NATO 7.62 cartridge, it experienced production problems and did not see general use until 1962. The Colt M1911 remained the standard sidearm, and the M-60 machine gun replaced the aging Browning Automatic Rifle, though photographs of the Marines landing at Da Nang in 1965 still show this venerable weapon in Marine hands.

Rather than the traditional corps or brigades, the Marines deploy as forces or units. These terms can be somewhat nebulous and even interchangeable depending on circumstances. This was true in Vietnam as well. When it became clear that the Army of the Republic of Vietnam was unable to defeat the insurgency of the Viet Cong and their allies of the Peoples Army of Vietnam, Marine and other units took an increasing role in the defense of South Vietnam, divided from its communist northern neighbor after peace talks following the French defeat at Dien Ben Phu.

From the first official deployment in April 1962 to the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident, Marines held a supporting, though increasingly aggressive, role. President Johnson's planners decided that the Marine Corps would establish their headquarters at the northern port of Da Nang, part of the I Corps area of control. I Corps, being the northern- most area that would be supported by US troops, was seething with 150,000 Viet Cong, and lay along the Demilitarized Zone that separated the country, making incursions by the PAVN and their Chinese advisors another frequent headache.

3 MAF

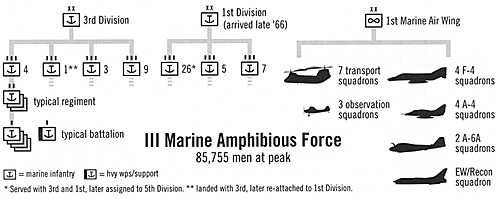

It was into this climate that the III Marine Expeditionary Force, renamed as the III Marine Amphibious Force to sound less colonialist, arrived in force on March 8, 1965. The initial landing at Da Nang consisted of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, a unit of two battalions plus attendant Hawk Anti-Aircraft missiles and other heavy weapons and transport. The numbers swiftly grew to twelve battalions before the end of the year. The III MAF was commanded by Major General William Collins, later succeeded by Major General Lewis Walt, who also commanded the 3rd Marine Division, which came ashore in stages after Naval shore facilities prepared the port of Da Nang for military use, or as the Joint Chiefs gloomily foretold, quick evacuation.

III MAF established units in several towns under their Tactical Area of Responsibility. In the town of Phu Bai, south of the provincial capital of Hue, one or two battalions based there to secure Army radio/intelligence groups. Most of the 3rd Marine Division was at Da Nang, plus the 1st Marine Air Wing. The 3rd Marine Amphibious Brigade, which consisted of a regiment and one air group, headquartered at Chu Lai in Quang Tin province. By July of that year a battalion and a helicopter squadron were also based at Qui Nhon. Other Marines units were based at Okinawa, or at sea as Special Landing forces, usually in company strength with supporting helicopters.

Marine "Forces" were considered self-contained units, like Army corps. The next lowest segment below a full-blown "Force", was the Division, then the Brigade, which was usually a reinforced regiment, then the Unit, usually in battalion strength. Divisions were typically four regiments in strength, each regiment having two battalions of 2 companies. Each company had four platoons. They were augmented by support units such as artillery batteries of six 105mm howitzers, and tank platoons, usually 3 squadrons of either M-48 or later M-60 tanks. They used the Hawk Anti-Aircraft missile for base defense.

Each Marine platoon had one M-60 machine gun and one M79 grenade launcher per squad. Marine Air Wings usually consisted of four or five air groups. At its height, the 1st Marine Air Wing had 2 helicopter groups, MAG 16, and MAG 36, which had seven transport and 3 observation squadrons, and two to three fixed wing groups, which had four squadrons of F4 Phantoms, four squadrons of A4s, 2 squadrons of A-6a's, and one electronic warfare/reconnaissance squadron. In 1969, the Bell AH1-G "Cobra" joined the 1st MAW's inventory.

Various Marine Regiments served in III MAF over the next three years, including the 1st, 9th, 3rd and 7th. The 4th and 26th regiments served under the 1st Marine Division, which joined III MAF in late 1966 and operated in Quang Tin and Quanag Ngai provinces. By the start of 1966, 38,000 Marines were ashore in the I corps area. Two regiments moved to Quang Tri and Thua Thin provinces. At the end of that year, their numbers swelled to 70,000, which caused a severe manpower shortage in the Corps. For the first time, conscripts were accepted. 19,000 were called up, tarnishing the Marines' all volunteer image.

Other changes were in store for the Corps. In order to simplify equipping units, the longer range, more powerful M-14 was replaced by the lightweight M-16, an assault rifle with a higher rate of fire. The "McNamara gun", named after the Secretary of Defense who was its most ardent supporter, was disliked by the men because it jammed frequently and did not have the stopping power of their old rifle. Refinements were made, however, and this weapon went on to become the standard US weapon for a generation. Teething problems plagued other equipment. The CH-46 helicopter was a high maintenance Marine item, suffering from engine breakdowns and tail section problems. Still, by the end of 1966, Marines had managed to kill 11,000 VC and PAVN soldiers, while losing only 1700 killed in action, and 9000 wounded, most of the later returning to duty.

1968

1968 was notable for the battle of Khe Sanh, in which 6000 men, including the 26th Marine regiment held off two PAVN divisions until relieved. During the Tet offensive, Marine units battled the length of I corps area in conjunction with XXIV Corps units such as the 101st Airborne and the 1st Cavalry Division. Total losses for the Viet Cong and PAVN troops for the Tet offensive exceeded 80,000, the majority lost in the III MAFs TAOR. III MAF losses were 4500 killed in action.

Other forces went to work on the Corps during this period. They maintained good control of their TAOR until 1969, when the new Nixon administration began the withdrawal process and initiated "Vietnamization." III MAF reached its peak numbers during 1968, with 85, 755 men ashore. The withdrawals began among a host of problems. The intense involvement of the Corps in Vietnam caused a crisis in its total structure. Base and Amphibious ship construction were at standstills. Media slants, anti-war sentiments, and inflation eroded morale and effectiveness.

The stigma of elitism was again trotted out before a public eager to believe that the military and government leaders were closet fascists. The Corps tried to gain strength of 243,000 men and 1004 aircraft of all types. They were dogged by high turnovers. In 1972 alone, 78% of personnel either joined or left the Corps. Separation due to drug abuse climbed from 94 in 1967 to 1700 in 1972. Racial tensions also grew, as well as incidents of the notorious "fragging", or the killing of officers by their own men. The Marine Corps had a much lower ratio of this heinous act that did the Army.

The Marines, which had gone ashore with high morale at Da Nang and enjoyed great success over their more numerous opponents, were but a shadow of themselves by 1971. Only a few security detachments, gun fire teams, and advisors remained. In 1975, five Marine helicopter squadrons and two battalions for security helped the evacuation of Vietnamese and foreigners as the victorious PAVN advanced, sealing the fate of the Republic of Vietnam. 9th MAB was the last Marine unit to depart. The Marines went home, not to parades, but to protesters and an indifferent country, too glad that the war was over.

Morale of the armed forces continued to sink, including the Marines. In a final footnote of that era, the Marines were called out one more time to attempt rescue of the crew of the USS Mayaguez in 1975, but coordination was so inept, that they landed under hostile fire after the crew had been released. 14 Marines and 4 Air Force and Navy personnel were killed, another 41 wounded.

A malaise began that would take years to erase. Marines went from the polished "The Few, The Proud, the Marines", to being considered a haven for misfits and minorities unable to make it in the real world. Fifteen years would pass before their stock would rise to pre-Vietnam heights and America would again honor its elite units.

Wargame Models

Finally, there is the matter of modeling the Marines for wargaming. A glance at their organization shows that their ratio of fighting men to the number of men it took to support them is very high. Also, four regiment divisions will be stronger than equivalent US Army Divisions. Amphibious Brigades will be more powerful that Army regiments because support units were incorporated into the MAF structure. Amphibious Units will be mere battalions, but again, due to the higher levels of training, ratios of combat/support troops, and the fact that in the first two years the Marines were all volunteer, their combat numbers would be 20-30% higher than equivalent Army units.

As a late veteran friend of mine summed up his experience as a Marine in Vietnam: "The Cong wouldn't attack Korean units at less than 10-1. They wouldn't attack Marines at less than 5-1. But regular Army, they'd attack at even odds."

The Marines' mobility is based on helicopter transport and amphibious capabilities. If carefully planned, an entire Division could be landed, but on short notice, probably no greater than a regiment could amphibious assault. Once ashore, their mobility was probably lower than the more motorized Army units. Their helicopter units were not especially powerful in assaults, because they were slow to adopt the Huey Cobra gunship. On a tactical level, the pre-M- 16 units would have a longer range, but lower rate of fire than opposing communist forces armed with AK assault rifles.

Their morale, melee, and initiative scores would probably be the highest of any units in the action. Even during the Nixon years, they would be superior units to regular US Army and ARVN units. Morale post 1970, however, would probably be either thirded or halved, and coordination would be seriously degraded. Games in which commands have to be given to units would also have to reflect the growing contempt of officers in the later years, though this should not degrade as much as morale overall. All in all, modeling Marines during the Vietnam era should reflect a tough, flexible and aggressive unit capable of dealing with an enemy on any terrain.

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 2

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.