Editor: The folloling article is an excerpt from Battleground: South Carolina in the Revolution and covers a little-known battle near Charleston, SC.

The battle of Stono Ferry lasted about an hour, but was far

from Charleston's finest. Consequently, it has been virtually forgotten

by South Carolinians who through the years have seen little reason to

celebrate the June 20, 1779 British victory.

The battle of Stono Ferry lasted about an hour, but was far

from Charleston's finest. Consequently, it has been virtually forgotten

by South Carolinians who through the years have seen little reason to

celebrate the June 20, 1779 British victory.

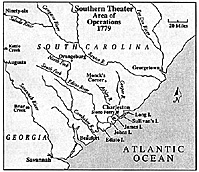

Large Map of Southern Theater of Operations (115K)

General Augustine Prevost [1] , after failing to capture

Charleston the preceding May 11-12 [2], had led his

red-coated warriors to James Island then across the Stono River to Johns Island.

The troops marched across the island to what was then Stow Ferry, in the vicinity of modern Church Flats, two miles or so southeast of Rantowles.

Their boats followed the Stono in its slow bend around the

northern end of John's Island. At the ferry, Prevost used his boats to

form a bridge across the river. Then, to hold the bridgehead on the

northern or mainland side, he set his men to building fortifications.

The works consisted of a circular redoubt on the east and two square

redoubts at center and on the western end. Redoubts were small,

enclosed forts from which the defenders could pour musket fire on the attacker.

Protecting the rear of the work was the river. To guard the front, the British built an abatis, a wall of felled trees, their branches pointed toward the enemy. The obstacle was designed to delay the attacker while the defenders kept him under fire from the redoubts.

Often these smal1 forts were armed with cannon, but contemporary sketches of the Stono Ferry position show artillery pieces on the ground just outside the walls of the redoubts, aimed to fire over, or through the abatis.

The entire Stono Ferry fortification stretched about 800 yards

along the river bank and was flanked on the right by virtually

impenetrable marsh and on the left by open space and then woods.

Initially, Prevost seems to have stationed a ship armed with cannon at

either end of the work as additional defense, but the vessels had been

removed by the time of the battle.

In addition to protecting the bridge of boats, the work furnished

a haven to Redcoats foraging on the mainland. Even more important,

it guarded the river retreat for the British through Wadmalaw Sound

to the North Edisto River and the sea. When General Prevost

returned to Savannah not long after the British occuppied lohn's

Island, he left his brother, Colonel J.M. Prevost [3] in command of some 1,500 men to defend the Stono Ferry post.

American Major General Benjamin Lincoln, who had returned

to Charleston after his foray into Georgia, planned to attack the work

on May 31st, but a reconnaissance showed the fortification far too

strong to risk assaulting and the plans were cancelled. During the

next two weeks, both sides accomplished little. Then on June 15,

Lincoln and Governor John Rutledge discussed new plans for an

attack. It would be made by the general's troops aided by a strong detachment from the city, which was to cross by boat to James Island to be ready to cooperate with him.

Weakened Defenses

Large Map of Charleston and Environs (95K)

The apparent plan was to evacuate the post and Lt. Colonel John Maitland was left with about 500 effectives to accomplish this chore, a maneuver which could prove dangerous without the boats for transportation and protection. Maitland had a single, armed flatboat capable of carrying 20 men.

With this, he spent June l7-l9 ferrying the sick and wounded, Negroes, Indians, horses and baggage to the southwestern tip of John's Island from where they could island hop down the coast

toward Savannah.

Determined to Attack

Informed that the post had been weakened by Prevost's

withdrawal, Lincoln determined to attack although his own force had

dwindled through desertions and expiration of enlistments. On the

16th, he ordered General William Moultrie to be ready to move a

detachment from the city at a moment's notice, an order that involved

collecting sufficient boats to transport the force.

Three days later, the 19th of June, Lincoln ordered Moultrie to

move these troops across the Ashley River to James Island and show

his strength to the British on adjacent John's Island if opportunity

offered. Theoretically, he would then be in position to cooperate with

Lincoln's attack or pursue the enemy on John's Island at the first

signs of retreat. However, Moultrie failed to collect sufficient boats.

Only half his men had crossed to James Island when he heard

Lincoln's guns beginning the attack on June 20 and the battle was

entirely over by the time he reached the Stono end of Wapoo Creek.

Lincoln, with about 1,400 men, had moved out of his camp a

few miles from Stono Ferry at midnight, June l9, and arrived before

the enemy works about an hour after daylight of the 20th. He knew

that the British senior unit, the 71st Regiment of Highlanders

[4], would, according to military custom, be at the post of honor on the right. Consequently, Lincoln switched his own regulars, the

Continentals, from their traditional post on the right to the left -- to

face the Highlanders [5].

The American right was composed of a brigade of North and South Carolina militia and two field pieces [6] . Behind them was a small reserve of Virginia militia [7], also with two field pieces. Both flanks were protected by light infantry and the cavalry [8] was posted a little to the right and rear of the reserve.

On the British side, about 40 Highlanders occupied the circular redoubt, and the major pan of the regiment was encamped between the circular and the central redoubts. The North and South Carolina [9] provincial troops manned the central redoubt and a German Hessian [10] regiment held the left redoubt.

Alerted Garrison

British pickets alerted the garrison about 7 am, and Maitland

sent out two companies of the Highlanders to feel out the attackers.

This was a normal reaction as small units of American light infantry

had harassed the fortification on several occaisions in the past. This

time, the Highlanders met more than they could handle. They were

badly mauled by the Continentals, but fought stubbornly, refusing to

retreat until all of their officers were dead or wounded Only 11 men

of the two companies made it back to the British lines.

Large Map: Tactical Battle (95K)

On the British left, the American militia pressed the attack and

the Hessians gave way. Seeing this, Maitland withdrew part of the

Highlanders from the right, where they were easily holding the

Continentals who were stopped by the marsh, and shifted them to the

left. They doubled-timed almost the length of the fontification and arrived in time to reinforce the Hessians who raIlied and returned to battle.

Lincoln finally succeeded in stopping the fire of the Continentals

and tried to get his men to charge. But enthusiasm of the moment had

passed and the troops refused. They simply renewed firing and the

battle continued until British reinforcements were spotted coming on

the run for the ferry. Lincoln, realizing he could not capture the work,

ordered a retreat. This caused a certain amount of confusion in the American line and Maitland immediately took advantage of it. He ordered a general advance.

Cavalry to the Rescue

Lincoln threw in the cavalry to stop this new threat. But the

British were old hands at handling a cavalry charge. They formed

two lines, closed ranks and halted. The first line dropped to one knee,

set the butts of their muskets on the ground, and presented a solid

row of bayonets to the charging horses. The second line remained

standing, then when the cavalry got close, gave it a full volley. This

stopped the charge. The front rank of infantry now rose and delivered

another volley while the rear rank reloaded. By this time, what was

left of the cavalry was in full retreat.

The Virginia militia of the American reserve was sent into action and managed to hold the British long enough for Lincoln to extricate his army in fairly good order. This ended the Battle of Stono Ferry, a clear-cut British victory and one of the toughest fought

battles on South Carolina soil during the Revolution.

The entire engagement last about 56 minutes. British casualties were 129 - 26 of them dead. American losses were a bit higher, about 165 of whom 50 were killed and the rest wounded. The British resumed their briefly interrupted withdrawal and by the night of June 24th had abandoned the Stono Ferry fortification. They moved down to the southwest corner of John's Island then, by various creeks and islands to Beaufort [11] where a strong British post was established under Colonel Maitland, who proved his reputation as a first class

fighter. Maitland's action in shifting his Highlanders under fire and later stopping the American cavalry charge stand out against relatively poor leadership on the American side.

Moultrie has taken most of the blame for the loss of the battle

much of it deserved. Certainly he was negligent in not collecting

sufficient boats to move all his 700 men at one time. Moultrie was an

extremely courageous man, but not a particularly successful officer.

He procrastinated and on more than one occaison failed to take

elementary precautions, even in defiance of orders.

Blame All Around

But to blame his failure to support Lincoln for loss of this battle

is carrying things too far. Even with sufficient boats to cross the

Stono River at Wapoo Creek, the distance across John's Island is too

great for Moultrie's force to have arrived in time to influence the

battle. Moreover, the British bridge of boats at Stono Ferry was

gone. Had Moultrie reached the ferry, he would have been stranded

across the river from the battle.

He could have fought the British reinforcements, but Lincoln's

fear of these is illusionary -- Maitland had been left with one 20-man

flat boat. Reinforcements, 20 men at a time, could scarcely have

affected the battle and if Moultrie had fought them on the John's

Island side, it would hew made no difference whatsoever to Lincoln,

who was on the mainland. If Moultrie had gone by boat, the distance

is more than 10 miles by water. He would never have arrived in time

to land in the rear of the British position.

Lincoln, on the other hand, deserves much more of the blame

than he generally has received. He had ample time, weeks in fact, to

thoroughly reconnoiter the position. Yet he ordered his Continentals

to assault a fortification completely unaware that they couldn't even

get to it across the marsh and creek. He also ordered them to go in

with the bayonet, yet the element of surprise, so necessary to such an

attack, was totally lacking. Assuming the position was approachable

in the first place, he should have had his troops in position for the

bayonet assault at first light, not still in the approach pbase an hour after daylight.

Although the battle had already been lost, Lincoln's apparent

fear of British reinforcements from John's Island would have been

eliminated by proper reconnaissance. He would have known that only

a small number could be crossed and been able to safely discount this threat.

Retreat before an alert, trained enemy is always a chancy business, particularly by relatively untrained troops such as the American militia, but Lincoln could do nothing less.

His disengagement under the circumstances was well-handled. He threw

in the cavalry, likely knowing this was a necessary sacrifice to gain

time. The few minutes they bought with their lives probably gave the

Virginia militia time to get into position to fight a rearguard action and

permit the rest of the army to withdraw with little further damage.

Without these moves, there is a good chance confusion would have

turn,ed to rout and the battle might have come down to us as the

"Massacre at Stono Ferry."

[1] General Augustine Prevost, formerly the commander of British Florida and the St. Augustine garrison, assumed command of all Crown forces in Georgia on January 15, 1779. By this time, the British controlled the principal settlements in Georgia: Augusta, Savannah and Sunbury.

More Battle of Stono Ferry

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. The following day, Colonel Prevost unintentionally paved the

way for this attack by drastically weakening the Stono defenses. The

colonel left for Savannah and took with him not only a large portion

of the troops, but all the vessels which formed the bridge between

John's Island and the fortification.

The following day, Colonel Prevost unintentionally paved the

way for this attack by drastically weakening the Stono defenses. The

colonel left for Savannah and took with him not only a large portion

of the troops, but all the vessels which formed the bridge between

John's Island and the fortification.

Lincoln had ordered the Continentals to hold their fire and

assault with the bayonet. However, near the abatis they found marsh

and a small creek barring their way. They also received a

concentrated blast from British artillery and infantry. Despite orders,

the Continentals returned the fire. The advance bogged down in the

marsh and the battle on this end of the line degenerated into a fire fight.

Lincoln had ordered the Continentals to hold their fire and

assault with the bayonet. However, near the abatis they found marsh

and a small creek barring their way. They also received a

concentrated blast from British artillery and infantry. Despite orders,

the Continentals returned the fire. The advance bogged down in the

marsh and the battle on this end of the line degenerated into a fire fight.

Footnotes

[2] On April 23, 1779 General Benjamin Lincoln led his American army from Charleston towards Augusta. To counter-act this initiative, Prevost advanced towards Charleston with his 2,500 man army. The American General William Moultrie, with a 1,000 man army positioned at Purysburg, just outside of Savannah, was obliged to fall back to Charleston in the face of Prevost's advance. On May l0, 1779, the British reached Ashley Ferry, about 7 miles up the Ashley River from Charleston. On May llth, the British defeated

a small force of American cavalry commanded by Casimir Pulaski.

This small action delayed Prevost's advance by a day. In order to gain additional time, South Carolina governor John Rutledge proposed negotiations with Prevost on May 12th, but both men were aware that this was merely a stall for time to enable Lincoln's army to return to Charleston from Augusta. Also on the 12th, Prevost commenced his withdrawal to Beaufort, South Carolina and Savannah, heading southwest from Charleston, via John's 1sland to

avoid Lincoln's approaching army.

[3] Lt. Colonel Mark Prevost of the 60th Foot.

[4] This was the first battalion with about 400 effectives. The

second battalion of the 71st Regiment had withdrawn with General Prevost.

[5] The American left was comprised of Henderson's battalion of light infantry (120 men) and Armstrong's North Carolina brigade consisting of the 4th and 5th North Carolina regiments - 250 men each.

[6] The American right consisted of Butler's North Carolina Militia brigade (610 men) and Brigadier General Isaac Huger's Brigade of South Carolina infantry (776 men), plus Malmedy's battalion of light infantry.

[7] The reserve consisted of Mason's Virginia militia, about 400 men.

[8] Pulaski's Legion cavalry (100 troopers) and Davie's North Carolina Horse (50 troopers).

[9] According to Greg Novak's Rise and Fight Again, A

Guide to the Armies of the American War of Independence in the Southern Campaigns, these were all North Carolina Loyalists numbering 150 men.

[10] The Hessian regiment von Trumbach, with 300 effectives.

[11] Maitland's force arrived at Beaufort on July 8, 1779. The majority of General Prevost's army returned to Savannah by ship. Maitland would remain in Beaufort with 900 men until September 12th, when he was summoned back to Savannah during the Franco-American siege of Savannah.

Historical Analysis

Large Map: Southern Theater of Operations (115K)

Large Map: Charleston and Environs (95K)

Large Map: Tactical Battle (95K)

Order of Battle

Back to American Revolution Journal Vol. I No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by James E. Purky

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com