The Need to Create a Myth

Whatever the reality of what happened, Lodi is notable for the 'spin' placed upon it by Bonaparte. The myth of the glorious military success has overshadowed both the actual events and the earlier part of the 1796 campaign. At what was in reality a rearguard action, there were political and military imperatives, which prompted Bonaparte both to fight the battle and then drove the creation of the myth.

Whatever the reality of what happened, Lodi is notable for the 'spin' placed upon it by Bonaparte. The myth of the glorious military success has overshadowed both the actual events and the earlier part of the 1796 campaign. At what was in reality a rearguard action, there were political and military imperatives, which prompted Bonaparte both to fight the battle and then drove the creation of the myth.

The events at Lodi have to be set against the background of inactivity on the German front prior to June, following on from relatively little fighting anywhere during 1795. Comparing the force sizes with those in Germany illustrates the importance placed by both sides on this theatre - and hence on their commanders' actions. Bonaparte's real success was in decisively out-manoeuvring the Austrians, thereby clearing the road to Milan. One factor particularly drove Bonaparte's advance onwards: Any new victory for the French Revolutionary army meant a political setback to Austria's interests and influence in Italy. Sardinia had been forced to seek terms and just before Lodi, the Duke of Parma.

In his Histoire des guerres des Francals en Italic (1805), Servan, the former French Minister of War wrote: "While the Austrians, who had been beaten in two battles, were obliged to retire on the Adda river, the rulers of Italy were forced to negotiate peace with Bonaparte. However, as today, it was battles and victories, not skilful strategy, which made the greatest news impact, so the campaign had to be capped by some glorious feat of arms, supposedly forcing a result that had already been decided.

The military theorist Jomini wrote: "Battles have been stated by some writers to be the chief and deciding factors of war. This assertion is not strictly true, as armies have been destroyed by strategic operations without the occurrence of pitched battles, merely by a succession of inconsiderable affairs ... But it is the morale of armies, as well as of nations, which more than anything else makes victories and their results decisive." Lodi marked a turning point for the French Army of Italy, giving them confidence in their capabilities and more importantly, in their leader's ability to march them to victory against the major regional power. Throughout April, about 50% of the French troops were hospitalised and many returned to their units in poor morale. Relaxing in Milan a few days after the battle of Lodi, the French troops must have felt that they had earned better times there by virtue of having won a battle. It was also - at least so the Napoleonic legend would have it - on the evening after Lodi, that these French soldiers nicknamed Bonaparte 'Le petit caporal'. Victory at Lodi had certainlv improved morale and confidence amongst his men, but Bonaparte also had to deal with his political masters.

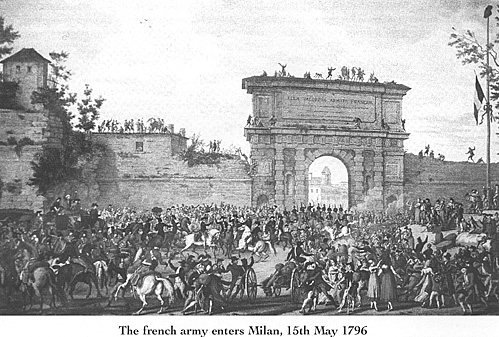

Bonaparte's achievement was considerable: Two months after his appointment in March 1796, he would be celebrating a triumphal entry into Milan, the wealthy capital of Lombardy. In just a few weeks, he had established his reputation as a militarly genius. However, this had come about by crushing the Sardinians and taking a key citv. More than anything else, a major victory over the Austrians would have the desired impact, ensuring the Sardinians would remain passive and enhancing the reputation of both Bonaparte and the French army,. The truth was that he had failed to destroy the Austrian army and would be unable to fulfil his prediction made just two weeks before. The Austrians had lost the battle, but it had not been the decisive one with Beaulieu. Like his Austrian opponent, Bonaparte would need more troops and supplies to sustain long-term operations.

The political pressure was still on the young French commander. Three years short of seizing control of the French government, Bonaparte was still subject to the instructions of the Directory, who had other plans in mind for him, designed not least to cut him down to size. The Directory viewed Bonaparte as a successful, but nevertheless, junior General. On 13th May 1796, he received the Directory's plans for subsequent operations: Kellerman was to command an observation force in Lombardy, while Bonaparte was to direct operations against Leghorn, Rome and Naples. The only way Bonaparte could resist this relegation to a minor side campaign would be to command the necessary support in Paris: if he won a major victory, he would have it - a simple rearguard action would not be enough.

Bonaparte had already claimed in his letter of 9th May to Carnot that he would pursue Beaulieu on the 10th. Noting the necessity of victory to keep the Sardinians out of the war and the political possibility of rewarding their neutrality with Lombardy, Carnot's response of the 17th

urged Bonaparte: "Do not lose sight of him: your activity and the utmost speed in your marches can alone annihilate the Austrian army, which must be destroved" [16]

(Carnot more than Bonaparte appears to have the originator of the change from 18th century aims of limited warfare to the concept of complete victory). Bonaparte had already moved to establish his version of events in a letter to Carnot of the day following the action, the 11th: "Beaulieu was positioned at Lodi with his troops in full battle order ... Beaulieu's battleline was smashed through ... Beaulieu fled with the wreckage of his army," The Bulletin repeats this as does the Government Commissar, Salicetti. The letter continued: "The battle of Lodi, my dear Director, gives the Republic all Lombardy. The enemy left 2000 in the citadel of Milan, which I shall immediately invest. You may reckon, in your calculations, as if I were in Milan: I shall not go there tomorrow, because I wish to pursue Beaulieu and to take advantage of his delirium to beat him again." [17]

For whatever reason, there was in fact no pursuit, but the claims and the despatch of a large convoy of plunder did the trick - having received Bonaparte's letter of the 11th, the Directory changed their response in a letter of 21st Ma y: "Immortal glory to the conqueror of Lodi; your plan is the only one to follow." [18]

Far from pursuing, Bonaparte marched to Milan, only resuming his pursuit of Beaulieu on the 22nd. As part of the process of consolidating his new Empire after his Coronation in December 1804, the growth of many myths was encouraged. Up to 1805, the now Emperor Napoleon had fought all his battles in Italy and even staged a fictional re-enactment of Marengo in June 1805. The heroic crossing of the Adda was treated no differently: That same year, Servan related the French strategy after crossing Po at Piacenza: "The route to Milan was open to the French, but it could not be secured for them until they had chased the Austrians firom the banks of the Adda". Aside from ignoring the fact that General Colli had already been ordered to move further east, leaving just a small garrison in Milan, the former French Minister of War's argument rests on a false premise, which has been regularly repeated by historians ever since. One is Steven T. Ross, who in his Quest for Victory. French Military Strategy 1792-1799 (1973) argues that after the French crossed the river Po, the Austrians sent a substantial force to Lodi, so as to defend Milan and the most important bridge over the Adda: "Although Bonaparte failed to crush the Austrian army, he did dislodge them from the Adda and opened the way to Milan." Clausewitz similarly indulges the myth: "no-one could have imagined that the reputation of the Austrian army would be so badly mauled. There were 7,000 men and 14 guns to defend a 300-pace long bridge over an unfordable river - under any conditions, a near impregnable position."

Bridges played a major role in 1796, both at Lodi and Arcole. Looking back over his career in his Memorial de Sainte Helene', the Emperor of Battles had to designate a military success over a major opponent as the start of his career. Napoleon took the view that: "The battles of Vendemiaire and even Montenotte did not bring me to believe that t was an exceptional person. Only after Lodi did the idea come to me that I could be a decisive player on our political stage. Only then was the first spark of great ambition born." His immediate entourage were happy to reinforce this assessment: Count Montholon wrote in his report on Napoleon's musings during his captivity: "Only on the evening of Lodi -- so Napoleon quite freely acknowledged -- did I believe myself to be an exceptional person and the ambition arose in me to achieve greatness, which had previously only occupied my thoughts like a fantastic dream."

The effect has lasted to the present day, but on that evening after Lodi, Bonaparte hadn't yet thought the future through: By then, he must have been informed from prisoner interrogations that he had only engaged Sebottendorl's rearguard. The campaign was still to be won and one of Bonaparte's main priorities would be to rest his men in Milan, before pressing on over the Adda. He was candid in assessing the day's events in a conversation with the Bishop of Lodi at dinner that evening : "Pero non fu gran cosa!" (After- all, it wasn't a major event!).

Several important battles would follow over the next year, but Lodi had given notice of the French determination to take on the Austrians in Italy The effect on the troops was probably more important. They had engaged and defeated the Austrians, numbers and commanders' long-term plans being unimportant, following which they could take Milan.

The French historian Stephane Beraud, who has recently written an exceptional study of the 1796-7 Italian campaign [19] succinctly places this battle in the overall scheme of events: "The Battle of Lodi was an action of only secondary importance, not to be compared with the actions at Castiglione, Arcole or Rivoli. Nevertheless, it holds a similar position in the opinions of contemporaries. Above all, it gave rise to the myth of General Bonaparte, who took the bridge at the head of his troops. In fact, he would only perform this feat of arms some months later at the bridge of Arcole. This legend was created by Bonaparte's soldiers, who honoured him with the title The Little Corporal'. At that moment, myth was already supplanting history."

[7] Published 1995

Sources as per Part 1 with the additional sources specified in the text.

Brilliant Strategy or Unnecessary Battle?

NOTES

[8] Kriege gegen die Franzosiche Revolution (1896). Vol. 1 p.436

[9] Phillips: Roots of Strategy }3001; 1 (rep. 1985), pp 417-418

[10] See for example: Semek: Die Artillerie im Jahre 1809: Mitteilungen des kuk Kriegsarchivs, Third Series, Vol.7 p.75).

[11] Anon. officer of IR42: Osterreichisches Soldatenfreund No. 52: 1st May 1851

[12] Phillips: Roots of Strategy Book 2 (rep. 1985), p.494

[13] 13) The Bonaparte Letters, V01.1 p.72

[14] Ditto, p.83

[15] Ditto, p.85

[16] Ditto, p.86

[17] Ditto, p.92

[18] Chandler: Campaigns of Napoleon (rep.1993) p.85

[19] S. Beraud: Bonaparte en Italie - Naissance d'un Strategie (1996)

Back to Table of Contents -- Age of Napoleon #37

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com