The 14th of the Line by Royer (1890s). This depiction is purely dramatic and did not occur.

Around him, soldiers of Legrand's division were already ripping up the village for firewood against the bitter cold. They had once been ordinary men, but this winter in Poland had destroyed their humanity. There was no pity in their eyes for the few remaining families who watched in disbelief. Their homes collapsed before them and the broken timbers in the fires sent showers of sparks into the freezing black night above their heads.

The temperature dropped lower and the swirling snow silently drew covers over the corpses. The survivors were grateful for the shelter afforded by the more solid buildings, and by the ugly stone church on its little hill. The Army had thrown itself without orders at the obscure Polish village all afternoon. They had fought savagely Into the dusk to win this shelter rather than face another night in the frozen wastes and icy north wind of this God forsaken country in the back of beyond. But of the hundreds that huddled in blankets and greatcoats that night on the cold floor of Eylau Church, nearly half would be dead or, wounded by the following evening.

Ensconced in the Post-Master' s old armchair, the Emperor Napoleon considered his situation. This storming of Eylau had upset his plans. The Russians, lighting their campfires barely a thousand yards away in the wintry gloom, were so close that battle next morning could not now be avoided. With only 45,000 tired men against perhaps 60,000 or more Russians, he would have preferred not to offer battle at all until the arrival on his right of Marshal Davout with 15,000 men. But now he had no choice but to hang on in the face of a substantially superior army until help could arrive. And with over 400 guns to oppose his 270 or so, hanging on would test both his own nerve and his soldiers' courage to the very limit ... or beyond.

He made mental calculations of distances and marching speeds, rising quickly from his chair, pacing up and down the room. His staff listened in silence to the tread of his boots, the creakin

of the floorboards. Davout MUST be in action by noon, or the Emperor might lose not just an army, but the fragile Empire. They waited for the architect of miracles to set his machinery in motion...

To M. le Marechal Davout, Duc d'Auerstadt... A secretary leapt to his pens.

The divisions of Friant, Morand, Gudin preceded by your light cavalry, to be on the march two hours before dawn on the village of Serpallen, to fall on the enemy's left flank.. The pen scratched away, while in a corner of the room, an ADC waited grimly to bear the message off into the night.

Since the early campaigns of Italy, where General Bonaparte's brilliance had first caught Europe's attention, Napoleon's ambition had grown upon him like a cancer. Self-declared Emperor, and Dictator of France by 1804, he had turned inevitably to the conquest of Europe, hammering

Austria and Russia in 1805, and annihilating the antiquated Prussian Army the following year. The

next target was Poland, already restless under her tottering Russian and Prussian Overlords, and

bewitched by Napoleon's offers of freedom and independence.

While diplomacy and whispered intrigue contintied unabated in the perfumed courts of old Europe, Napoleon's mounting successes on the battlefield scared the Tsar of Russia for the moment at least, into supporting the weak King of Prussia against the Napoleonic threat. The subsequent campaign in Poland soon ground to a halt due to the terrible roads and arctic weather, and the

army went gratefully into winter quarters, Napoleon in Warsaw spent the nights with his new mistress, the beautiful Maria Walewska.

Surprise Offensive

When the Russians turned to face the French at Eylau, the Master was, for the first time in his Imperial career, caught off-balance. Bennigsen, the Russian Commander-in-Chief, (at right) was suddenly given the chance of sweeping the whole glittering Napoleonic Empire into oblivion.

A pale and withered-looking man of 62, the scarred and wily Hannoverian was not without military skill, but he lacked resolve. He sat among his maps, stroking his forehead gently with his fingers. He considered his moves all evening and gnawed at his lips.

When he finally turned in for the night on bed of straw in a peasant's hovel at Anklappen, the wind howled outside and rattled the little wooden shutters of the windows. In his few brief hours of rest, did he dream of Victory, or face nightmare visions of defeat?

In the house at Eylau, meanwhile, the Emperor made his plans. Soult's 4th Corps to take the left, nailing itself to the ground at Eylau. Napoleon had called him the Premier Tactician of Europe. His troops called him "Iron Hand." Tomorrow, there would be no need of tactics--just the Iron Hand. Augereau's 7th Corps to the right. Crippled with rheumatism and barely able to mount a horse, Augereau had asked to be excused from duties in the coming battle. Request refused. One more day in the saddle, Augereau, one more day.

The Guard, to be placed as usual in reserve, at the Emperor's personal disposal. Better-paid, higher-ranked, prized and pampered by its master, it was a standing joke that even the Guard's transport mules were to be addressed as donkeys in deference to their superior rank. Moreover, they hadn't seen action since the creation of the Empire in 1804. Fierce looking in their tall bearskins and martial bearing, would they really fight if the time came?

On the left again, and guarding Soult's flank from any Russian move to get round him, the dashing Lasalle with his light cavalry. A painting of the time shows him in fashionable baggy trousers and sleek, waxed moustaches, puffing away with gusto at a huge Meer schaum pipe.

'Any hussar not dead at thirty is just fortune-hunting', he'd once blurted out with a sneer and a toss of his head. In two years' time, at 34, he would fall stone-dead from his horse at the head of his men, a bullet between the eyes.

It was not really enough, the Emperor thought, but it would have to do. He considered. Ney. Marshal Ney had 10,000 men. He was several miles distant, but he COULD be called to the battlefield. But Ney was in action against the Prussian Lestocq, hounding the tired Germans and swallow them up little by little. If Ney were to give up the pursuit, Lestocq, too, would be freed to regroup and march to join the Russians. Napoleon hesitated. No. Later, he would regret ft.

Amid the deepening snow, cavalrymen scoured the empty barns for fodder, while their mounts snorted and shivered the freezing night air. Some of the army found shelter in the wretched

Polish hovels. Milhaud's cavalry slept with their horses at Rothenen. But most of the men, freezing, hungry, exhausted, spent the night of the 7th huddled on open ground around their campfires, large or small. Baron Larrey, the Chief Surgeon, recorded 30 degrees of frost shortly before dawn on the 8th. The soldliers talked, dozed, grumbled or lit their pipes. They may have sat and stared at the thim crackling flames under the vast indifferent sky till the smoke, or their silent thoughts brought tears to the corners of their eyes. Legrand's men in Eylau were the luckiest. Across the valley, the Russians bore their suffering with the quiet stoicism which has always mystified the West. They were on the move by 5 a.m. the next morning.

On the Move

In the gloom before the dawn, Davout's light cavalry scouts had already brushed briefly with the Russian picketts posted beyond Serpallen. A shadow inthe dark, a horse' snort, or a man's curse was enough to take aim and shoot at ghosts. A few scattered shots from the saddle and the silence fell again like a thick blanket. The Frenchmen were gone to report their findings. As

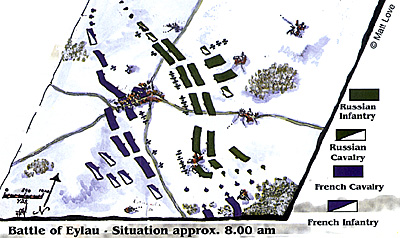

the dawn came up, barely distinguishable from the night, Bennigsen prepared his final dispositions.

Three divisions in a great column in reserve behind his centre, together with sixty cannon. Snow settled every second on the gleaming brass barrels: the draught-horses shook themselves noisily while the gunners waited, banging arms together or blowing into their red raw hands. The divisions of Tuchkov, Essen, Sacken and Ostermann made up the main battle-line, two battalions of each of the twenty or so regiments deployed in three-rank lines, while the third battalions waited behind. On the Russian right, Markov' s cavalry, and beyond them the bearded Cossacks roamed free on their little horses, each armed with a long lance and a brace of pistols. Semi-irregular troops, at best unreliable in a pitched battle, the French regarded these marauders as barbarians from a bygone age. They would suffer cruelly at their hands in 1812.

In and around Serpallen were the regiments of Baggovut, supported by the tattered remains of Barclay's command, defeated by the advancing French two days before at Hof. Kamensky's division and the rest of the cavalry were held in reserve. But what made Napoleon catch his breath as he swept the Russian position with his spyglass from the top of Eylau Church, were the GUNS. Three massed batteries, of sixty, forty and seventy cannon respectively, waited silently ready to roar, spit out fire and death at the French. And between the massed batteries, the divisional batteries waited too, gunners swinging their port fires, poised for the word of command.

At 8a.m., the Russign line erupted. The cannon leapt back wild animals with the sudden recoil. As the smoke blossomed upwards and the gunners rolled their pieces forward again, the men of Soult's Corps heard the iron balls whizzing overhead. 'No point ducking' said a sergeant of cavalry to a terrified conscript as he visibly flinched. 'They're cannonballs, not turds. You'll never hear the one that hits you.'

The Russian gunners were already swabbing out the smoking barrels and preparing another

salvo. Soon, the bombardment became a continual roar, the Russian guns loading and firing and draging the guns forward with methodical efficiency. Soult's regiments took it mostly in silence. An occasional cough or a curse, even a laugh at a private joke. Soon enough the Russian artillery began to find the range; Casualties began to occur, in ones and twos at first, more, and the soldiers had to bear the screams of their comrades. The officiers walked slowly along the line,

searching for signs of weakening. There were none.

The French artillery, for their part, refused to be swamped. Firing faster with more accuracy and at more exposed targets. For the moment, they gave as good as they got.

Still in the Eylau church tower, Napoleon now estimated nearer 70,000 than 60,000 Russians. Visible only fleetingly between snow flurries and dark blotches of thickening smoke, they stood deployed in their mute compact masses. Retreat was out of the question, attack would be suicidal.

Yet against the growing storm of artillery fire, the Emperor could not expect his little army to stand inactive for long. As the battered heaps of dead and badly woulnded were being dragged away steadily from Soult's grim battleline, Napoleon turned his glass southeast towards Serpallen. He could see elements of Davout's first division coming up, and Baggavut's troops, outflanked, recoiling easily from the little hamlet.

What of the rest of the Corps? Would the attack be sufficiently developed in time before the remainder of the army withered away in the face of this relentless Russian bombardment? Suddenly, he was dictating an order.

'M. le Marechal Ney, with the whole of the Sixth Corps, to abandon pursuit of Lestocq, and march by Althof and Schloditten to join the left of the army.'

Napoleon was rattled.

More Eylau

Broken bodies and rubble were being cleared away from the Post-Master's house at Eylau when the Emperor galloped up in a flurry of plumed and braided horsemen to establish Headquarters there for the night.

Broken bodies and rubble were being cleared away from the Post-Master's house at Eylau when the Emperor galloped up in a flurry of plumed and braided horsemen to establish Headquarters there for the night.

Antoine-Charles-Louis Lasalle and Louis-Nicoloas Davout

Antoine-Charles-Louis Lasalle and Louis-Nicoloas Davout

But in January 1807, the Russians launched a surprise offensive which had the Emperor hurrying back to his army. Surprised in their turn, the Russians were driven back. But his long lines of communication necessitated large deployments of troops and stretched the horse-drawn supply trains beyon dtheir limits.

But in January 1807, the Russians launched a surprise offensive which had the Emperor hurrying back to his army. Surprised in their turn, the Russians were driven back. But his long lines of communication necessitated large deployments of troops and stretched the horse-drawn supply trains beyon dtheir limits.

The Reserve cavalry under the flamboyant and posturing Prince Murat (at right holding trademark horsewhip in Jirbal's painting 'Murat at Eylau') to be positioned behind Augereau, to act as circumstances might dictate. No great general or tactician, the tall, handsome Murat owed his pre-eminence among the Marshalate to his having married into the Bonaparte family. Backed by his dandyism and bravura, he nevertheless lead one of the most extraordinary and spectacular cavalry charges in history in the battle of 8th February.

The Reserve cavalry under the flamboyant and posturing Prince Murat (at right holding trademark horsewhip in Jirbal's painting 'Murat at Eylau') to be positioned behind Augereau, to act as circumstances might dictate. No great general or tactician, the tall, handsome Murat owed his pre-eminence among the Marshalate to his having married into the Bonaparte family. Backed by his dandyism and bravura, he nevertheless lead one of the most extraordinary and spectacular cavalry charges in history in the battle of 8th February.

8am

8am

Introduction

10am

Charge of Murat

12 Noon

11pm

Eylau Order of Battle

Eylau Map Large (very slow: 245K)

Eylau Map Jumbo (extremely slow: 406K)

Back to Age of Napoleon 29 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com