Robert Craufurd: The Final Assault Part 1

Lieutenant Gurwood was given command of the Light Division Forlorn Hope and Lieutenant Mackie of the 3rd Division party. As far as the Forlorn Hope was concerned, Subalterns who survived the prospect of certain death could hope for brevet promotion, but there were no campaign medals or reward for any of the rank and file, officers and NCOs. For them survival would mean status during their military career, and the prospect of many a free drink at their hostelries during retirement, but that was all. Despite this there was no shortage of volunteers - in the case of the Light Division 'nearly half the division'.

George Napier had already volunteered to lead the

storming party, and this, supported by Colonel Colborne,

was confirmed by Craufurd as the Division neared La

Caridad. Craufurd instructed him to get the necessary

volunteers 100 from each regiment. In Napier's words he

went to the three regiments, viz, the 43rd, 52nd and Rifle

Corps and said 'Soldiers, I have the honour to be appointed

to the command of the storming party which is to lead the

Light Division to the assault of the small breach. I want 100

volunteers from each Regiment - those who will go with me

come forward. [21]

Chosen volunteers shook hands with each other,

inwardly weighing up their chances and relishing the

thought of plunder - should they survive.

Storming Plans

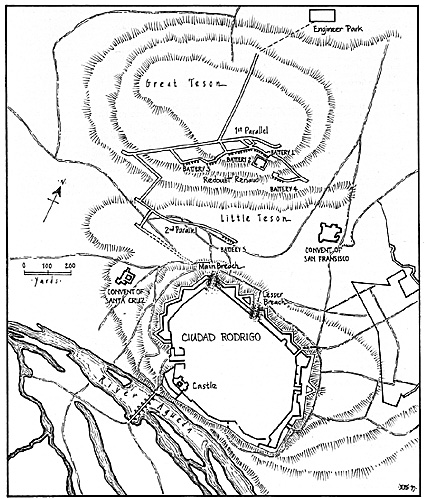

The main breach was to be stormed by General Picton

and the Third Division. Craufurd expressed an interest in

storming it - shades of the old rivalry - but the Light Division

was ordered to the Lesser Breach. Picton's division were to

issue from the First Parallel. Campbell's brigade was to

advance from behind the Santa Cruz Convent in two columns.

The 5th Regiment was to effect an entrance into the outer

ditch at the gateway north of the Castle Gate.

After mounting the wall of the faussebraie by means of

the 25-foot ladders they were carrying, they were to sweep

along it to the left to the main breach. The light company of

the 83rd Regiment and the 2nd Cacadores were to cross the

Agueda by the bridge from the suburb. They would then

escalade and capture a small outwork below the Castle from

whence the fire of the guns might interfere with the attack of

the 5th.

The other column, the 94th Regiment, also advancing

from the Santa Cruz Convent was to descend into the outer

ditch by means of 12-foot ladders at a point between the

gateway and the main breach. It would sweep along it to its

left and clear it; both the 5th and 94th thus eventually joining

the right of the attack on the main breach. This was to be

made by Mackinnon's Brigade moving out straight from the

Second Parallel. His advance was to be covered by the fire

of the 83rd Regiment which would remain in the Parallel. It

would be preceded by 180 sappers carrying haybags to

throw into the ditch in order to break the fall of the men as

they descended into it. Companies from the Light Division

would protect its left flank.

Craufurd was to form up his division in the rear of the San

Francisco Convent, ready to storm the Lesser Breach. Three

companies of the 95th Rifles, provided with three 12-foot

ladders, would descend into the ditch midway between the

two breaches. These companies were to carry ten axes with

which to destroy any defences or obstacles and working to

their right were to clear the ditch up to Mackinnon's left at the

main breach.

Vandeleur's Brigade was to approach the San Francisco

Convent from the right with the ladders and to descend into

the ditch to the right of the small breach, passing to the left

of the small ravelin and from there to make for the top of the

breach. On reaching the fausse-braie they were to detach five

companies to the right and assist Mackinnon's attack.

The main body, on reaching the summit of the main

walls, was to do the same. Barnard's Brigade was to form

up behind the San Francisco convent in support. All the

columns were to detail parties to keep down the fire of the

enemy and Wellington particularly ordered that "The men

with the ladders, and axes, and bags must have arms,

those who storm must not fire." [22]

Finally, there were to be feint attacks by Pack's

Portuguese Brigade on the San Pelayo Gate. [23]

Last Orders

Craufurd's last orders to his Division were as follows:

Four companies of the 1st Battalion 95th Rifles under

Major Cameron to line the crest of the glacis and fire on

the rampart;

One hundred and sixty men of the 3rd Caadores, carrying

hay and straw bags, twelve 1 2-foot ladders and some

axes.

The " Forlorn Hope" consisting of an officer and twenty-

five volunteers under Lieutenant Gurwood of the 52nd;

The storming party; three officers and a hundred volun-

teers from the 43rd, 52nd and 95th Rifles under Major

George Napier of the 52nd;

The main body of the division under Craufurd consisting of

the remainder of Vandeleur's Brigade, namely the two bat-

talions of the 52nd and some companies of the 95th

Rifles;

Barnard's Brigade, consisting of the 43rd, some compa-

nies of the 95th Rifles and the 1 st Ca,cadores to remain in

reserve and to close on Vandeleur's Brigade when it

reached the breach.

Barnard was to detail four companies of the 95th Rifles

to man the Second Parallel at 180 yards from the walls and

keep up a sharp fire on the defenders.

The Light Division formed up north of the walls of the San Francisco Convent at nightfall and whilst waiting for orders to advance, Harry Smith, Brigade Major to Craufurd came up to some of the Rifle officers and said "One of you must come and take charge of some ladders if required." George Simmons at once volunteered and taking some men sent to the Engineers' camp where he was given some ladders as ordered by Wellington, of 12 feet in length.

On his return Craufurd, realising Wellington's mistake,

ungraciously scolded poor Simmons, as he realised that the

ladders needed to be 25 feet. Simmons, crestfallen, went

back to the Engineers' camp and handed the task to a

Portuguese captain who supplied ladders of the necessary

length.

Immediately it became dark, General Picton formed the

3rd Division in the First Parallel and approaches, and lined

the parapet of the Second Parallel with the 83rd Regiment,

in readiness to open on the defences. In the meantime

General Craufurd formed the Light Division in the rear of the

San Francisco convent.

Before the Division moved into position, Craufurd

addressed his soldiers in a voice described by Costello as

"more than usually clear and distinct: Soldiers, the eyes of

your country are upon you. Be steady, be cool, be firm in the

assault. the town must be yours this night. Once masters of

the wall, let your first duty be to clear the ramparts, and in

doing this, keep together.

Then he called as they started to move

off: "And now lads for the breach." [24]

Signal

The Light Division waited for the signal. Costello wrote:

I could not help thinking at this awful crisis when all most

probably were on the brink of being dashed into eternity, a

certain solemnity and silence among the men, deeper than I

had ever witnessed before. With hearts beating, each was

eagerly watching for the expected signal of the rocket, when

up it went from one of our batteries. [25]

The Light Division crossed 300 yards of open ground

from the convent, towards the breach. The stormers, not

waiting for the Portuguese who were detailed to carry the

haybags, and who arrived late, raced up the glacis, jumped

12 feet down the counterscarp into the ditch and surged up

the exterior slope of the fausse-braie. The attackers suffered

little loss, their first advance not having been spotted by the

defenders, but once they reached the ditch they were met by

furious fire of grape-shot and musketry.

The Forlorn Hope, going too far to the left, escaladed a

damaged earth traverse [26]

and had to descend, with the result that the first troops

actually into the breach were the stormers under Napier.

Such confusion in the heat of battle was understandable,

amid the noise, smoke and battered fortifications.

George Simmons describes it vividly: The breaches were

made in the curtain, before which a traverse was fixed in the

ditch to protect and strengthen it. In my hurry, after

descending into the ditch I mistook the traverse for the top of

the breach, and as the ladders were laid against it, I

ascended as well as many others, and soon found our

mistake. We crossed it and slid down directly opposite the

breach, which was soon carried.

He continues: A faint ray of light shone upon the battlements of the fortress and presented to our view the glittering of the enemy's bayonets as their soldiers stood arrayed upon the ramparts, and the breach, awaiting our attack; yet nevertheless, their batteries were silent, and might warrant the supposition to an unobservant spectator that the defence would be but feeble. .. [Later] A cloud that had for some time before obscured the moon, which was at its full disappeared altogether and the countenances of the soldiers Ishowedl .. a look of severity bordering on ferocity.

Access was easy once the Light Bobs had located the

breach, for it was only blocked by a gun jammed across it

and not retrenched. The gun was fired, and Napier was

struck down at close quarters. Colborne and other officers

were wounded, but the survivors pushed on, led by Captain

Uniacke and Lieutenants Johnston and Kincaid of the 95th

who gained the top and "with a furious shout, the breach was

carried and our men swept into the place."

While the Light Division columns were advancing to the

assault, Craufurd had kept to their left and reached the edge

of the glacis about sixty yards to the left of the point where they

had descended into the ditch. Here he remained giving

instructions "at the highest pitch of his voice."

Craufurd's End

Colborne wrote: "I remember hearing Robert Craufurd's

squeaking voice [presumably hoarse with the excitement of

the battlefield! crying out, "Move on will you 95th, or we will get

some who will." Shortly afterwards there came in his direction

an intense fire of musketry from the parapets of the fausse-

braie and ramparts opposite and at very close range, for the

ditches both of the fausse-braie and ramparts opposite and

at very close range, for the ditches of both were very narrow

at this point, and the place had no covered way. [27]

He was struck by a musket-ball which passed through

his arm, broke through his ribs, passed through part of his

lungs and lodged in or at his spine. The shock was so great

that on falling he rolled over down the glacis. [28]

Shaw-Kennedy, his ADC, half dragged and half carried

him to a spot "where an inequality of ground protected him

from the direct fire from the place."

Colborne continued: After Iying for a few minutes in this

situation, he said to me that he was mortally wounded and

that he felt he was dying. I expressed my grief that he had

such a feeling and a hope that he was mistaken, in answer

to which he reiterated his opinion that he was dying. I then

asked him if I could do anything for him. To this he replied

that I could not as all his affairs were perfectly settled.

I then asked him if he had anything to communicate to

Lord Wellington. After considering a little, he said that he did

not recollect anything that he had to communicate to Lord

Wellington, and that there was only one thing I could do for

him, which was to say to Mrs. Craufurd that he was quite

sure that they would meet in Heaven.

After this, he lay for some time quiet and without

speaking. Recovering himself in some measure from this

quiet, he said that he felt a little better. I then proposed to

attempt to raise him and if possible he should proceed to the

suburb. To this he agreed, and leaning heavily upon me, he

succeeded in getting to the Convent of San Francisco. On our

approach to this, he met a medical officer of the Rifles who

made enquiries as to the wound and thought that the arm

alone was injured, and he pointed out the place in the San

Francisco where General Craufurd should be taken for

examination. [29]

While Craufurd was awaiting medical attention in the

San Francisco suburb his ADC found a house where he

was eventually moved. On his return, the General's

diagnosis was confirmed, that there was no hope of

recovery.

Wellington had no idea of the seriousness of Craufurd's

wound and wrote to the Secretary of State: [30] Major General

Craufurd likewise received a severe wound while he was

leading on the Light Division to the storm, and I am

apprehensive that I shall be deprived for some time of his

assistance.

Wellington met Shaw-Kennedy within the city walls and

learned that this was a vain hope. [31]

By chance I met Lord Wellington at the Salamanca gate

on the morning of the 20th, and he asked most anxiously for

Craufurd. I gave him an unfavourable report of his state. His

Lordship called afterwards and saw Craufurd and they

conversed together for some time. Craufurd congratulated

Lord Wellington on the great advantage he had gained by

taking Ciudad Rodrigo, to which his Lordship [Perhaps

realising that the patient's days were numbered! replied

something in these words, 'Yes, a blow, a great blow indeed.'

[32]

Robert Craufurd was a loner, with few personal friends.

One of them was Brevet Major Campbell, who, together with

Shaw Kennedy hardly left his side, as his life ebbed to its

close, while General Charles Stewart, who had been a family

friend for many years, looked in.

Gone

On the 22nd, Craufurd seemed a little better and

conversed for a long time with Stewart about matters

military, enquiring about the assault and the movements of

the enemy. He was in much pain, and sent apologies to

George Napier, in the room below, for keeping him awake

with cries resulting from his wound, and wishing him a

swift recovery.

At 2 o'clock on the morning of the 24th, Campbell wrote a

more cheerful account of his condition to Charles Stewart.

But shortly afterwards, having bidden Campbell tell his wife

how much both she and the children meant to him, he fell

into what those about him imagined to be a comfortable

sleep from which he never woke. Charles Stewart,

presumably briefed by William Campbell, wrote to Fanny

Craufurd:

His pulse gradually ceased to beat, his breath grew

shorter and his spirit fled before those near to him were

conscious he was no more, so easy was his passport to

heaven.

The life which he had described to Fanny as a kind of

storm was now at peace. Wellington decided that he should

be buried within the Lesser Breach, stormed by his Division a

few days earlier. A young subaltern named Gleig, later to

become Chaplain general to the Army joined Wellington's

forces on the day of Craufurd's death and has left us with a

well documented description of the funeral.

As soon as the fatal issue of his illness became

apparent, directions were given to the artificers to prepare his

coffin, and he was laid in that on the evening of the day he

died. In the meanwhile, orders were issued directing the

forms to be used in committing his body to the earth and it

was in obedience to these orders that his own favourite

division appeared this morning under arms. Having

advanced to the house where his body lay, the Division

proceeded on, with arms reversed, between a double row of

soldiers of the 5th Division, who with their muskets likewise

pointing to the ground, lined the road on each side. This

done, so as that the rearmost company of the Division should

line with the house itself, the troops halted till the coffin, borne

by his sergeant majors, and having six field officers as

supporters, came forth.

The word was given to march, the several bands striking up slow mournful airs, and the coffin was followed, first by General Stewart and the aides de camp of the deceased as chief mourners, and then by Lord Wellington, Marshal Beresford and a long train of staff and general officers. In this manner we proceeded along the road until we gained the very breach, in assaulting which the brave subject of our procession met his fate, where we found that a grave had been dug for him and that he was destined to lie on the spot where his career of earthly glory had come to a close. The regiments being formed into close columns of battalions, took post as best they could, about the grave towards which the coffin, headed by a chaplain advanced Arrived at the brink of the sepulchre the procession paused, and the shell was rested upon the ground; and then I could distinctly perceive that among the six rugged veterans who had borne it, there was not a dry eye, and that even of the privates who looked on, there were few who manifested not signs of sorrow such as men are accustomed to exhibit only when they lose a parent or a child. [33]

Tribute

On returning from the funeral Craufurd's soldiers paid a

spontaneous tribute to his training which had made them

so special.

For as the Light Division returned from the grave of their

late commander, there lay in its way deep slush and mud,

and as this was approached there passed down the ranks a

low buzz. The men drew themselves together and plunged

into the mire. Not another sound was heard, it was the last

voiceless tribute of these gallant fellows to the memory of

their lost chief. [34]

Wellington himself paid further tribute to Craufurd's

memory in a public letter to the Earl of Liverpool:

Although the conduct of Major General Craufurd on the

occasion on which these wounds were received, and the

circumstances which occurred, have excited the admiration of

every officer in the Army, I cannot report his death to Your

Lordship without expressing my sorrow and regret that His

Majesty has been deprived of the services, and I of the

assistance of an officer of tried talents and experience, who

was an ornament to his profession, and was calculated to

render the most important services to the country. [35]

In the House of Commons a humble address was unanimously presented to the Prince Regent directing that he will be graciously pleased to give directions that a monument be erected in the cathedral church of St Paul, London, to the memory of Major General Robert Craufurd, who died in consequence of a wound he received on the 19th day of January 1812, while he was gloriously leading on the Light Division to the storm of Ciudad Rodrigo, by which that fortress was wrested from the possession of the enemy. [36]

During this short motion, Perceval referred to the fact that the country had lost a most able, skilful and gallant officer. In seconding the motion, Lord Castlereagh (half brother of Charles Stewart) said:

The character of the late lamented Robert Craufurd

rested on its own merits and was but to be appreciated by

the testimonials of the gallant division of which he bore

command; that the division on his return from leave had

recorded his merits by an involuntary burst of applause when he just appeared on parade, the testimony and admiration of his conduct which the illustrious Army had shown would serve as a remembrance of his departed worth. [37]

The Light Division themselves were sad, for trained by Sir

John Moore as many of its officers and men may have been, it

was to Craufurd and his leadership that they owed their

nickname of The Division. He made them feel "they were

something greater than themselves." Rifleman Harris, the

cobbler was one of his greatest fans, and his memories of

his General remained undimmed for many years. Charles

MacLeod of the 43rd detested him, but nevertheless in

describing the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo in a contemporary

letter to his father, he could stili write:

You will have heard of the death of poor Craufurd. I regret

it very much, for although I was not on the terms one would

wish to be with one's General, he was nevertheless always

particularly civil to me, and liked the regiment. [38]

Kincaid probably spoke for many when he said - "Like

many a gem of purer ray, his value was scarcely known until

lost." Charles Stewart took charge of the disposal of his

personal effects, sending papers, writing case, books etc,

back to England, but selling his horses and campaign

furniture by public auction in Spain, the proceeds of £

3,000 being sent to Fanny. [39]

He wrote sadly to Robert's brother Charles on

26th January

Alas! My friend, of our small party of five, who were

headed by you and first knew each other in '96, how many are

gone, and how cruelly others have suffered, poor Anstruther

ldied at Corunna], and Robert and yourself who have gone

through so much! Proby and myself alone remain.

Such is the sadness of War.

The most conservative estimates on our part were that it would take at least three weeks for the city to fall. But General Dorsenne, who was responsible for this place had appointed General Barrie to command this garrison, a detestable officer, indecisive and a poor leader. General Dorsenne left the garrison with second-rate troops not even two thousand strong. and he neglected this vital frontier town, and was not concerned that he had had no reports from Rodrigo for two months, and did not make it his business to find out what was going on.

[41]

Even a small detachment of 300 cavalry would have

improved matters. General Barrie once attacked seemed

incapable of making any useful dispositions with his troops.

The fortified convent, which the Spaniards used so effectively,

making a powerful contribution to the defence of the town,

was not even occupied, and the enemy entered it unopposed.

The redoubt fell after a lively battle, but with no loss, the day

the city was invested. The artillery only began firing from the

16th. The walls were breached on the 18th: the assault took

place at night. The breach was defended with a certain

amount of success, but a feint attack by escalade succeeded

and the town was lost to us.

Never has such an operation been carried out with so

little difficulty. Thus in eight days from time of the English

investment they had obtained their objective. With such a

miserable defence, bearing so little resemblance to our

plans, we had no chance of arriving in time to save the city

from the English.

to: M C Spurrier, Ian Fletcher, John Hoyle and Michael Howard (Royal

Green Jackets ret'd)

EPILOGUE

The recapture by Wellington of Ciudad Rodrigo [40]

was not only one of the most important turning points of the

Peninsular war but one of Wellington's finest achievements

resulting, inter alia, from lessons learned from the early

sieges of Badajoz, and careful planning over many months.

Wellington reckoned that he could retake the city in 25 days

(Ney's timetable) but in fact completed the operation in

twelve. So Robert Crauford did not die in vain.

40Let Marshal Marmont, understandably bitter, but grudgingly

generous in defeat, have the last word; The town of Rodrigo

which was defended by the Spaniards and attacked by the 6th

Corps, commanded by Marshal Ney, resisted us for 25 days

from the date of the investment and cost us great loss of men

and armaments. The defences of this place were sound,

augmented by an outwork, a redoubt on the Great Teson,

looking down on the town which the enemy needed to capture

before attacking the main garrison. I set up, as a fortified

support to this redoubt, a big convent in the suburbs.

Acknowledgements and Notes

[1] Wellington was not in a position to promote Major

Dickson after this exercise: such matters were controlled by the Master

General of the Ordnance.

[2] For the Portuguese and Spaniards to supply bullock carts to the English was dangerous - the French would have regarded such transactions as treachery.

[3] A fever caught on the Walcheren expedition in 1809. More British troops were killed by the fever than by enemy action.

[4] Glacis - The downward slope of a rampart of a covered way, extending gradually into the sunounding tenain within a distance of about 200 feet.

[5] Enceinte - A wall of earth, ten to fiDeen feet high, generally lined with stone or brick, sunounding a fortified place and forming its main defence.

[6] Fausse-braie - A hwer wall buih several yards outside the main fortress wall providing shelter for riflemen or artillerymen firing apinst the besiegers before they entered the ditch. Once captured, it served as a means to scale the

fortress walls. It might also have to provide additional protection for the main

wall in a bombardment to force the besiegers to pound a breach in both walls.

[7] Ravelin - A detached work composed of two faces, forming a salient angle and raised before the counterscarp (the outer slope or side of a ditch, opposite the fortress wall, usually faced with stone or brick to make the besiegers'

descent into the ditch more difficult).

[8] "Journal des Sieges fait ou soutenus par les francais dans le Peninsule de 1807-1814" by Colonel Belmas.

[9] Chevaux de frise - portable barriers equipped with sword bbdes etc. and used for blocking breaches.

[10] Wellington was lucky. The Marialva trestle bridge was washed away by floods on 2 February - two weeks aher Ciudad Rodrigo was recaptured.

[11] "Il suppose vrai tout ce qu'il voudrait trouver existent." Marmont's observations on the Imperial Correspondence of February 1812 Memoires,

iv, p 512

[12] Memoires du Duc de Raguse

[13] Marmont to Berthier, Valladolid, 13th January 1812.

[14] "History of the 52nd Light Infantry" by Moorsom, p 156, (2nd edition)

[15] Wellington's Despatches, Wellington to the Earl of Liverpool, 9 January 1812, vol 8, page 518

[16] Craufurd to his wife, 8th January 1812

[17] The consensus among the besiegers would seem to agree with this view. Tomkinson says in "Diary of a Cavalry Officer", p 124, that the governor at the time they stormed was going to dinner, and had not made his appearance for the last two days in the ramparts. Tomkinson considers that he behaved very well, but with his weak garrison could not have held out until Marmont's arrival. Kincaid's view CRough Sketches", p 251) was that "The governor directed much more of his attention to keeping an unremitting fire of shot and shells at the working parties in the trenches during the whole of the siege, than to a judicious defence of the breaches "

[18] Belmaa writes: "Lord Wellington reckoned that the breach would soon be operational and called on the governor to surrender. General Barrie

replied that he and his garrison would rather be buried beneath the ruins of the

city than do any such thing. He posted his troops on the ramparts and on the

fausse-braie, at the same time organising frequent patrols in the trenches."

[19] Belmas writes: "They worked furiously at the interior defences including the area at the foot of the breach. Beams were placed on the parapets which could be thrown on to the besiegers if they attempted to escalade." I have not yet found any reference to beams in English sources.

[20] Barrie's report in the Appendix to Belmas's "Sieges", p 299.

[21] Napier - "Early Military Life of General Sir George T Napier", p 179

[22] Supplementary Despatches, vol vii, pp 253-55

[23] Called "Santiago Gate" in the Orders.

[24] Costello - Adventures, p 96

[25] Ibid

[26] Traverse - A parapet eight to ten feet in thickness, built of earth to cover an entrance or breach as well as part of a fort against enfilade or

reverse fire.

[27] Covered way - a path round the outside of the ditch usually with a banquette (a ledge from which soldiers stood to fire over a wall or parapet) and parapet on the outside. Sometimes used to describe a communication trench.

[28] Willoughby Verner, "History of the Rifle Brigade", p 344

[29] General Sir James Shaw Kennedy to Sir William Fraser, Bart, Bath, 13 June 1861. Although this account was written many years later, it was

something that he never forgot, even after nearly 40 years.

[30] Dispatches, Vol 8, p 528 (April 1837 edition)

[31] General Sir James Shaw Kennedy to Sir William Fraser Bart, Bath, 13 June 1861.

[32] "Words on Wellington " by Sir William Fraser Bt, 1889, p 181, has the following dramatic description of Wellington paying his last respects to

General Craufurd. The technology in question seems years ahead of its time.

One of the most striking pictures I have ever seen was shown at the Gallery

of Illustration. Among a series of dissolving views was one of the Duke (sic)

before the High Altar, in the cathedral of Ciudad Rodrigo, looking at the coffin

of General Craufurd, which was placed on a bier immediately in front of it.

[33] The Funeral of General Craufurd by G R Gleig, the Gem, (London) 1829.

[34] History and Campaigns of the Rifle Brigade, Part II, 1809 1813, by W Verner (London) 1919, pp 353-354

[35] Wellington to the Earl of Liverpool, Gallegos, 29 January 1812.

[36] House of Commons Report, 22 February 1812.

[37] House of Commons Report, 22 February 1812

[38] OBLI Journal, Vol IV 1895, p 105

[39] This may seem an enormous sum, but Captain John Mills wrote in his diary for 28 January 1812, "General Crauford's effects were sold. The produce of the sale could not amount to less than 3000. There was a complete service of plate

for 16." For King & Country - The letters and diaries of John Mills, edited by Ian

Fletcher, Spellmount, p.109.

[40] Memoires du Duc de Raguse, Tome 4, livre XV, p 79

[41] The accusation that he was not told of English troop movements in the Ciudad area was unfair. Thiebalt, the Salamanca governor, had been warning

him for some weeks of English activity, but so entrenched were the views of Marmont and the Emperor that these warnings were treated as Cassandra-like "wild and whirling words" and ignored. For example, Thiebalt wrote to Dorsenne on 1 January, based on information from a Spanish spy that the Anglo Portuguese army had crossed the Agueda, but no action was taken. (Memoires du Duc de Raguse, iv, pp 342-3)

Robert Craufurd: The Final Assault Part 1

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 25 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com