When did Zieten inform Wellington of the Commencement of the French Offensive?

This, in turn, was the cause of the Duke of Wellington's failure to concentrate his army and move it as rapidly as the circumstances required.

This version of events would appear to have originated from the Duke of Wellington himself. In his 'Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo', written in the third person and dated 24

September 1842, he claimed that (1)

'The first account received by the Duke of Wellington was from the Prince of Orange, who had come in from the out-posts of the army of the Netherlands to dine with the Duke at three o'clock in the afternoon. He reported that the enemy had attacked the Prussians at Thuin . . .'

Napier, the famous Peninsular War historian, in his Waterloo Letter dated 28 November 1842, mentioned a similar story coming 'from the Duke's mouth'. This was that 'Blucher picked the

fattest man in his army' i.e. Muffling, to ride with an express to me, Wellington, and that he took thirty hours to go thirty miles'. (2)

According to this version of the events, Wellington first

heard of the outbreak of hostilities at the Duke of Richmond's ball late

in the evening of 15 June, apparently shortly after 11.00 p.m.

Gleig had served with Wellington in the Peninsula and was an

admirer of the Duke. In his work on the Waterloo Campaign, first

published in 1847, he at first followed the line given by the Duke in

1842. (3)

Gleig later went on to translate Brialmont's biography of

Wellington with the tacit approval of the Duke. Gleig elaborated this

story in this Life of Wellington, where he wrote: 'An orderly dragoon,

it appeared, whom General Ziethen had early sent off to announce to

the Duke the commencement of hostilities, had lost his way . . .'

(4)

Gleig gives no reference for whom this dragoon might have

been, or where this version of the events might have originated, but

one could describe him as a 'source close to the Prime Minister'.

Other Opinions

Lady Longford preferred the first version, writing in her Life of Wellington that: 'About 3.00 p.m., nine hours after Napoleon's start, the Duke received his first report. A Prussian officer covered with dirt and sweat galloped into Brussels with a much delayed despatch

sent by General Zieten from Charleroi at 8 or 9 A.M.' (5)

Uffindell, in his recent work on the Battle of Ligny, while stating that the Prussian messages '. . .came between 4.00 and 6.00 p.m.', also gives credence to Napier's version. (6)

Schom, in his work on the One Hundred Days, following the

lead given by Longford, takes this myth to extremes. He claims that: '.

. . Ziethen refused to inform Wellington of the large French

encampment at Beaumont on 13 and 14 June, or to send him a

message post-haste regarding the initial French attack early on the

fifteenth . . .'

(7)

It is interesting to note how each successive writer

appears to have embellished the Duke's original story. However,

none of them has given any clear indication of the basis in

documented fact for their particular version of these events.

In 1848, in the third edition of his History, the great classic on

the Waterloo Campaign, the elder Siborne, having investigated the

issue in some detail, took the trouble of refuting the accusation that

Zieten had failed in his duty to communicate the news of the

outbreak of hostilities to the Duke. (8)

So which version of these events is correct, the two

different versions, one certainly coming from Wellington, and one

apparently originating from him, or was Siborne justified in defending

Zieten against his accusers?

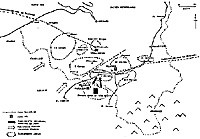

In June 1815, the Allied forces in the Low Countries were

deployed across a wide front. There were two main reasons for this.

Firstly, there were several lines of advance towards Brussels,

Napoleon's immediate objective in the campaign, that he could take,

and each needed to be covered.

Secondly, as there were difficulties in supplying the large

concentration of Allied troops in a relatively small area in the

Netherlands, the Allies were forced to spread out their men

somewhat more thinly than they wished.

The net result of this necessary deployment was that the two

wings of the Allied forces, under the command of the Duke of

Wellington and Field Marshal Blucher, would have to march farther to

concentrate than the French would to capture Brussels. Any delay in

this concentration had potentially disastrous consequences, so

speed was of the essence.

The Allied plan as drawn up at the conference at T rlemont on 3

May 1815 required the Prussians, if attacked first, to delay the French

for as long as necessary. This would enable Wellington to bring up

his forces, which he would have to do with haste.

The Allied armies were like a coiled spring waiting for

the pressure to be released. Once this happened, they would

move into action rapidly. It only needed for the two senior Allied

commanders to give the go ahead for everything that had been

planned and prepared over recent weeks, and particularly in

the preceding days, to fall into place.

Tension

In the second week of June 1815, tension in the Allied

outposts, both the Dutch and the Prussian, along the frontier

between the Netherlands and France mounted. Reports of the

concentration of the French 'ArmEe du Nord' together with news of

Napoleon's departure from Paris for the front come in from

numerous sources. There was little news other than such reports.

The commanders of the outposts reacted by putting their troops

on alarm. The Netherlanders assembled by battalion every morning,

remaining under arms until dusk. This way, they expected to be able

to react to any French offensive with a minimum of delay. (9)

The Prussians too had taken what measures they could in the circumstances. From 12 June, the outposts were placed on full alert and the detachments were moved into so-called alarm houses at

night. The two brigades (in 1815, a Prussian brigade was the equivalent of a division in other armies) deployed along the threatened sector of the border were instructed, in the event of a

French attack, to assemble at their rendezvous rapidly.

(10)

All the local commanders were convinced that the French offensive was imminent, and that its immediate target was going to be the Prussians. They reported the situation to their relevant

headquarters who assured them of appropriate action once the French attack commenced.

Commanders of formations to the rear of the outposts were also aware of the situation. For instance, Lord Hill, commander of Wellington's II Corps: '. . .was in the constant receipt of information respecting the movements of the enemy, which he communicated to the Duke of Wellington at Brussels. On the 13th of June he was informed that, at one o'clock in the morning, the French outposts and pickets all fell back towards Maubeuge, and that it was generally

believed that an attack was intended on the 15th. (11)

Preparations had been made to get the troops in a position to

be able.to move off rapidly once hostilities commenced. For example,

the Royal Horse Artillery had been issued with biscuit, campaign

rations, on 10 June. (12)

A Plan

The Duke of Wellington and Prince Blucher had agreed a plan

of action to deal with such an event at their meeting at Tirlemont on 3

May 1815. Were the French to attack the Prussians first, the latter

were to delay the French as much as possible through a rearguard

action before moving part of their army to the Sombreffe position,

where they would stage a major holding action allowing both the

Prussians and Wellington to complete their concentration.

Once both armies were assembled, they would, having

together, but not individually, the superiority of numbers, then go over

to the offensive. In any case, a battle would have to be fought before

Brussels as it was judged inappropriate for Napoleon to be allowed

to take this prize. On receipt of the news from his outposts of the

likely French offensive,

Blucher sought from Wellington an assurance that the latter

would give his support. On 14 June, Wellington, through

MajorGeneral von Muffling, the Prussian liaison officer in his

headquarters in Brussels, confirmed his intention to concentrate his

army at Nivelles. (13)

From here, he would not only be in a position to move in support

of the Prussians, but would also be able to counter any French

movement via Mons, another possible line of advance on Brussels.

As far as the troops at the front and the Prussian

headquarters were concerned, the situation was clear. A French

movement would result in their finger being taken off a coiled spring,

and the plans long agreed on would be implemented. On the surface,

Wellington's headquarters was giving the same message.

In the flush of victory on the morning of 19 June 1815, the Duke of Wellington wrote his official report on the events of the Waterloo campaign, his first communication to his political masters since the outbreak of hostilities. (14)

In this report, addressed to Bathurst, the Secretary for War, when

mentioning the outbreak of hostilities and the French attack on the

Prussian positions at Charleroi, Wellington stated: 'I did not hear of

these events till the evening of the 15th'. (15)

Four days earlier, at 10 p.m. on 15 June, Wellington had

written a letter to the Duke of Feltre at the French court-in-exile in

Ghent outlining developments that day. This letter contained the

paragraph: (16)

'I received news that the enemy attacked the Prussian posts

this morning at Thuin on the Sambre, and appeared to be menacing

Charleroi. I have heard nothing from Charleroi [headquarters of

Prussian I Corps] since nine o'clock this morning'.

The implication here is that Wellington had in fact

received news of the French attack early that morning. A letter

from Zieten, commander of the Prussian I Corps, brought to him

by 'Kolonnenjager' Merinsky, indeed contained the news that the

French had attacked Zieten's outposts. (17)

In his 'Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo' dated 24

September 1842 in which Wellington replied to criticisms made by

Clausewitz of his handling of the Campaign of 1815, the Duke was

insistent of the time at which he first heard of the events or the

Franco-Belgian frontier. His statements, written in the third

person, included the following: (18)

'It appears by the statement of the historian IClausewitzl that

the posts of the Prussian corps of General Zieten were attacked at

Thuin at four o'clock on the morning of the 1 5th; and that General

Zieten himself, with a part of his corps, retreated and was at

Charleroi at about ten o'clock on that day; yet the report thereof was

not received at Bruxelles till three o'clock in the afternoon.'

The inconsistencies in Wellington's versions of these events

are self-evident, particularly the great variance in the times

given in two documents written within four days of each other,

namely those of 15 and 19 June 1815. So just when did Wellington

first hear of the commencement of the French offensive; by 9 a.m.,

at 3 p.m., or in the evening? What could explain these

inconsistencies in the Duke's statements on the issue?

The Allies, and particularly the Duke of

Wellington, had a well organised

system of information gathering that they

used to observe developments. The Duke

had an extensive network of agents

throughout France, and, thanks to the time

he had spent as Ambassador in Paris,

good contacts in royalist and government

circles. Furthermore, he was protector of

Louis XVIII and the French court-in-exile in

Ghent.

Wellington did not suffer from a lack

of information; he received news daily

from his spies in Paris who made use of

the express post that ran from Paris to

Belgium. In contrast, Blucher's system

was apparently badly organised. (19)

The hub of Wellington's

information gathering operation was at

Mons, on the main road from Paris to

Brussels, and close to the border

between France and the Low Countries.

In charge of this operation was the experienced Hanoverian officer, Major General Freiherr von Dornberg, a Peninsula veteran. He obtained information from spies, scouts, farmers,

travellers and the large number of French crossing the border, sending frequent reports to Wellington's headquarters in Brussels. (20)

These reports were sent via the headquarters of the Prince of Orange, commander of the I Corps of Wellington's army, which were further along the road to Brussels at Braine-le-Comte: here, the Prince usually noted the contents of tha information received for his own use

before passing it on to Wellington's own headquarters.

In Brussels, FitzRoy Somerset, the Duke's Military Secretary, took receipt of

these reports. The divisional and brigade commanders along the front also

collected and shared information received from their outposts and other sources. These commanders included Major-General Behr, commandant of Mons, Major-General van Merlen, commander of the 3rd Brigade of Dutch cavalry in St. Symphorien and Major-General von Steinmetz, commander

of the Prussian 1st Brigade in Fontaine l'Eveque. Zieten, commander of Prussian I Corps reported directly both to Wellington in Brussels and Blucherin Namur. It was considered that these arrangements would cover all eventualities.

Volume X of Wellington's 'Supplementary Despatches' contain

the following messages sent from Dornberg to the headquarters in

Brussels in the days prior to the commencement of hostilities: (21)

When, from 12 June, it was clear that a French offensive

was imminent, Zieten considered changes in his dispositions at the

front. However, all that was done was to recommend the outposts to

be more alert. Various detachments were moved into so-called alarm

houses at night, and the brigades were ordered, in the event of an

attack by superior numbers, to assemble rapidly at their rendezvous.

(22)

Netherland Measures

The Netherlanders too had undertaken measures so as not

be surprised by any French offensive. Major-General Baron de

Constant Rebeque had, on 9 June, ordered his 2nd and 3rd Divisions

to be prepared to march off from their assembly points at

short notice.

This resulted in the troops' daily routine consisting of getting

up at 3.30 a.m. every day, gathering at the battalion assembly points

by 5 a.m., and remaining there under arms until 7 p.m., when they

returned to their quarters for the night. The cavalry and artillery

received similar orders. (23)

From the quantity and consistency of the information coming

into Wellington's headquarters, it would seem almost certain that the

French were indeed on the point of launching an offensive. In fact,

Colonel Sir William Howe de Lancey, Deputy Quartermaster General,

had drafted orders for such an event. Lt.-Colonel Sir George Scovell,

an Assistant Quartermaster-General, witnessed this. His account

reads as follows: (24)

'On the 13th June I went about 6 a.m. to his [De Lancey's]

Office for some papers I wanted, and to my astonishment found him

writing - he told me he had been employed all the night preparing the

Duke's Orders for all the Divisions to move to a certain point; but that

these orders were not to be sent off before Napoleon had committed

himself to a certain line of operations.'

A copy of these orders can be found in Hudson

Lowe's papers. (25)

At 8 a.m. that morning, Lord Hill sent the following message

to De Lancey: (26)

'I forward to you three Reports of the Intelligence containing in these Reports of the Enemy's assembling in great Force near Maubeuge, which have reached Hd. Quarters before you

receive this. With respect to Col. Estorff's request to send infantry to St. Ghislain, I have desired Sir Henry Clinton to keep in view the Instructions he has received, directing him to collect his Divn. at Ath in case the Enemy sd. attack, consequently he will not send Infantry to St. Ghislain, or further in advance than they are at present'.

A further report from an unnamed source sent at the

same time that day reads as follows. (27)

'I have the honour to acquaint Your lillegiblel that Yesterday

on my return from Gand, and last night, I received several Reports

from the Frontier stations that the Enemy have assembled a very

large Force near Maubeuge, for which purpose Troops have been

marching from Valenciennes, Laon & Mezieres. It appears that

Buonaparte has not joined the Army, but Soult is certainly with it'.

At 9.30 a.m., Dornberg sent his first report of the day. This

read as follows: (28)

'It appears that the troops have only been concentrated near

Maubeuge to be reviewed. They began yesterday to march in

different directions, some to Beaumont, and some to Pont sur

Sambre, where it is said a camp will be formed. About 48 pieces of

ordnance shall have taken that route.

'A regiment of the line, the 51st, coming from Lille, has passed the day before yesterday Valenciennes, and marched in the direction of Avesnes. A great number of waggons have been

put in requisition on the frontier to carry provisions, it is said, for eight days'.

At 3 p.m., Dornberg forwarded the following information to

Brussels immediately on receiving it:

(29)

'I have just now got the following intelligence, which I copy

literally:

"Le quartier general du ler. corps d'observation est a route

sur Sambre depuis trier. Le General d'Erlon y etoit attendu. La

traitterie de cuisine de Buonaparte etait trier a Avesnes a quatre

heures et demie, mais il n'y etait pas lui meme.

"Toutes les troupes se concentrent sur Maubeuge et

Beaumont. On suppose l'armee de 80,000 hommes jusqu'a

Beaumont, et de 100,000 hommes jusqu'a Philippeville. Chaque

division a six ou huit pieces de campagne.

"Les trots regiments de cavalerie appartenant au ler. corps

d'observation qui 'talent entre Cambrai et Valenciennes ont passe

trier derriere Avesnes, sans entrer dans la ville, se portent

aussi sur Maubeuge.

"Toutes les troupes qui Etoient dans les environs se dirigent

sur ce point.

"II n'y a que 100 hommes a Bavay".

Piquets

'The cavalry piquets in front of Valenciennes at

Quivrain are withdrawn. A man coming from Lille saw the

garrison of that place march out, and also that of Dunkerque

passing Lille: they shall both have passed Valenciennes, crying

"dive l'Empereur! "'

The above intelligence indicates that the French

army was moving east, thus away from the Dutch positions and

towards those of the Prussians, and, as Bonaparte was

present, were likely to launch an offensive.

At 5 p.m., the Prince of Orange sent the following

information to Wellington: (30)

'I am just returned from the front, where all is quiet, and

where no change has taken place. I received the "Gazette de

France" of the 12th, which I enclose herewith, in which it is said that

Buonaparte left Paris to come down to this frontier on the 11th at

night'.

Napoleon at the Front

This report confirms that there was no longer any

French activity in the Mons area, and that Napoleon was at

the front. This would indicate that the French were likely to

launch an assault on the Prussian positions.

Muffling heard from Zieten that the French were

concentrating in front of his outposts and that he expected their

offensive to be against his I Corps. (31) Zieten's information on the French intentions came from Merlen in St. Symphorien. (32)

Major-General von Pirch II, commander of the 2nd Brigade in

Zieten's Corps, reported that the French had closed the border. (33) Until then, there had been a

constant flow of persons and information from France to Belgium.

Such an action on the part of the French was an indication of an

intention to invade Belgium shortly.

Indeed, the sum of information received by the Prussian

headquarters in the last few days led Lt.-Colonel Sir Henry Hardinge,

Wellington's representative there, to report to the Duke on the

evening of 14 June that: 'The prevalent opinion here seems to be that

Buonaparte intends to commence offensive operations'. (34)

Wellington's response was to assure the Prussians that he

had taken all measures to ensure that his army would be able to

concentrate either at Nivelles or Quatre Bras twenty-two hours after

the first cannon shot. (35)

The correctness of the Prussian assessment of the situation

was confirmed by a report sent by Dornberg at 9.30 p.m. to Blucher's

headquarters at Namur in which he stated: 'according to the French,

the attack will be early tomorrow morning'. (36) This message arrived in Namur at

1 a.m. on 15 June.

The scene was now set for the commencement of hostilities.

It seemed certain to the Allied outposts along the border, both the

Anglo-Dutch-German and the Prussian, that the French were going to

attack the next morning. The Prussian headquarters expected this,

and Wellington had indicated he was prepared to come to their aid

both quickly and in force.

The French troops assembled for their offensive before dawn

that morning. Pajol's Cavalry Corps moved off towards the frontier at

2.30 a.m., preceded by the cavalry division of Vandamme's Corps. At

3 a.m., Reille's Corps set off in the direction of the Prussian outpost

at Thuin, followed by d'Erlon's Corps. (37)

The French assault on Thuin began shortly after sunrise, at

about 4 a.m., when a battery of Reille's Corps opened fire on

the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr Regiment,

which, expecting the French attack, was already under arms.

(38)

The noise of this bombardment could be heard at Zieten's

headquarters in Charleroi, about 15 km away. Anticipating that the

French offensive would commence that morning, Zieten had tried to

snatch a few hour's sleep. He went to bed fully clothed, expecting to

have to react quickly to events. The cannon fire at 4 a.m. woke him.

Zieten noted: (39)

'I sprang out of bed, fully clothed, woke all officers, ordered 'Kolonnenjager' Merinsky, Captain von Felden, Major Count Westphal to ride to me immediately, dictated one letter in German, one in French, that hostilities had begun and sent Westphal with the first to Namur to

Field Marshal Blucher, Merinsky with the second to Brussels to the Duke of Wellington.'

As the message to Blucher contained the information that

musketry was also to be heard, then the use of cannon and small

arms fire by the French, together with previous reports of the

concentration of large numbers of their forces with the presence of

their Emperor, then this was taken to indicate French intentions.

These messages were sent off before 5 a.m., (40) that to Blucher arriving at around

8.30 a.m., (41) and that to

Wellington by 9 a.m. (42) Blucher

ordered the concentration of his remaining three corps. (43)

Wellington Fails to React

Wellington did not react, apparently believing the French

assault to be a feint covering their withdrawal into the interior of

France, and appears to have kept Zieten's news to himself, or at

least amongst his close associates. (44) Certainly, Muffling was not informed of this news; he

evidently first heard of the news when a messenger sent to him

personally from Zieten arrived in Brussels about 3 p.m. (45)

News of the outbreak of hostilities appears to have reached

Mons just before 9.30 a.m. (46)

Although it may seem surprising that the Allied post nearest

where the French offensive began should be the last to hear of it,

atmospheric conditions had prevented the sound of the French

cannonade from reaching even the right wing of Steinmetz's

Brigade.

Thus Major von Arnauld, the officer Steinmetz sent to

communicate the news to his nearest Allies at St. Symphorien, had to

spend time spreading the alarm amongst the more westerly Prussian

outposts he met on his way. Arnauld arrived at the headquarters of

Merlen's cavalry brigade at 8 a.m. (47)

From here, the news was passed on to Mons, where it

arrived at 9.30 a.m.; and Dornberg forwarded it to Wellington via

corps headquarters at Braine-le-Comte, where it arrived about

midday. From Braine, the news of these hostilities was sent on to

Brussels two hours later by Sir George Berkeley, who had waited for

the arrival of other news before sending a communication to

Wellington. (48)

His despatch would have arrived at Wellington's

headquarters by about 5 p.m. Fortunately, at 10.30 a.m., Behr,

at Mons, had written to the Prince of Orange in Brussels. (49)

This news of the French attack reached Braine-leComte

about midday, (50) and from

there, it was forwarded to Brussels immediately, being

delivered to the Prince there shortly before 3 p.m. (51)

News Travels

News of the outbreak of hostilities had so far reached

Brussels directly from Charleroi, this report arriving by 9 a.m.; from

Behr via Mons and Braine-le-Comte, arriving in Brussels about 3

p.m., and from D^rnberg via Braine-le-Comte, arriving about 5 p.m.

The news circulated throughout Brussels on the morning of 15 June.

Lt. Basil Jackson, an officer on Wellington's staff, related: (52)

'Early on the 15th June 1815, we learned that the French

were crossing the frontier at Charieroi'.

An officer of Picton's Division present in Brussels noted:

(53)

'About three o'clock of the afternoon of that day. our officers were sitting at Dinner at

the Hotel de Triemont, where we had our mess, when we heard of a commotion, or greater stir

than usual, having arisen in the city; presently some Belgian gentleman came in and told us, that there had been an "affair of posts" on the frontier, and that the French had suffered a repulse.'

Throughout the morning of 15 June, Zieten kept both Brussels and Namur informed of

developments on his section of the front. About 8.15 a.m., he sent a report to Bluchers (54) indicating that his outposts were falling back. The next significant item of news he reported was the fall of Charleroi, which occurred about 11 a.m.

This time, instead of sending this news to Wellington in Brussels, he sent it to Muffling, who received it about 3 p.m. Muffling immediately passed this information on to Wellington, evidently just before the Prince of Orange received his news from Mons. (55)

The fall of Charleroi was surely an indication that the French movements were more

than a bluff.

Until 3 p.m., Wellington had believed that the French offensive was merely a feint, covering Napoleon's withdrawal into the interior of France; but now, within a short space of time, he had a fresh report from Zieten brought by Muffling with the news of the fall of Charleroi together

with the Prince of Orange disturbing his dinner with confirmation of the news the Duke had received that morning from Zieten.

Even this news did not elicit a reaction from Wellington, who, it would appear, continued to regard the French offensive to be a bluff. It would take news from Namur to make him begin to

change his mind.

Zieten's message of 5 a.m. arrived at the Prussian headquarters

in Namur about 8.30 a.m., (56)

confirming the Prussians'view that the French offensive was going

to commence that morning and be directed against their positions.

Half an hour later, Blucher sent Zieten a message informing him that

the army was going to move towards the front. (57)

Orders had been issued for that on receipt of the news

from Zieten, which was seen as confirmation of what the reports of

the previous day had indicated, that is that the French were going to

invade the Low Countries, first attacking the Prussians at Charleroi.

At 11 a.m., Blucher wrote to Zieten again, informing him that his

headquarters were moving to Sombreffe, (58) where Blucher, in accordance

with the plan agreed with Wellington at their meeting at Tirlemont on 3

May, had planned to stage a major rearguard action in the event of a

French offensive on Charleroi.

At noon, Blucher sent a message to Muffling in Brussels updating

him on the situation and the measures he was taking. (59) This despatch would have arrived

in Brussels before 6 p.m., about the same time as the report from

Berkeley. At last, Wellington reacted. His first orders of the day were

issued almost half a day after the Prussian command had sent out

theirs.

On the basis of information received on 14 June, the Prussians

considered the outbreak of hostilities imminent. Indeed, the news of

the first gunfire at the front was enough for Blucher to order a

concentration of this army. Wellington was privy to the same

information, yet did not react in the same way when he had given

several indications that he would.

The popular version of the events of the morning of 15 June 1815 as given in several English language accounts of the campaign is that the Prussians were tardy in informing their British allies of the French assault on their section of the front in the Netherlands, and the resulting commencement of hostilities.

The popular version of the events of the morning of 15 June 1815 as given in several English language accounts of the campaign is that the Prussians were tardy in informing their British allies of the French assault on their section of the front in the Netherlands, and the resulting commencement of hostilities.

The Coiled Spring

Wellington's

Reports

Allied Espionage

In the preceding weeks, rumours

of an impending French invasion of the

Low Countries came and went along with

news of royalist uprisings throughout

France, creating a confused situation. It

was unclear whether Napoleon was at

last going to start his attack, or whether

he intended withdrawing into the interior.

In the preceding weeks, rumours

of an impending French invasion of the

Low Countries came and went along with

news of royalist uprisings throughout

France, creating a confused situation. It

was unclear whether Napoleon was at

last going to start his attack, or whether

he intended withdrawing into the interior.

14 June

1815

June 14 was a busy day in the various Allied

headquarters, as rumours of Napoleon's appearance at the

front grew. Some dismissed this talk as just another false alarm,

while others took the situation more seriously.

June 14 was a busy day in the various Allied

headquarters, as rumours of Napoleon's appearance at the

front grew. Some dismissed this talk as just another false alarm,

while others took the situation more seriously.

The Morning of 15 June

Brussels & the Outbreak of Hostilities

The Fall of Charleroi

Namur - The Prussian Reactions

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 22 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com