On the 11 December 1845, the Sikh army, fortified by the knowledge that it was an astrologically fortuitous day, moved across the Sutlej towards the British. Gough immediately began to move his 13,000 men from Ambala towards Ferozepore, held by another 10,500. The Ludhiana force of 7,000 men left the fort and moved to meet Gough. The 16th Lancers were stationed at Meerut, some 280 miles from Ferozepore, part of a force of 10,000 men under Sir John Grey. They thus missed the two opening battles of the campaign, Mudki (18 December 1845) and Ferozeshah (21-22 December 1845). These two battles had cost the British regiments dear, but had resulted in pushing the Sikhs back over the Sutlej. Grey's units left Meerut in elements between the 10th and 16th December, and reached the main army at Ferozepore on 6 January 1846.

One of Gough's divisional commanders was Sir Harry Smith, late of the Rifle Brigade and the Light Division (there, that got Stephen Petty interested). On 16 January he was ordered to take one of his brigades together with some cavalry and force the surrender of the small forts of Fatehgarh and Dharmkot. The Sikhs were using these posts to cover foraging expeditions south of the Sutlej. By 2:00 p.m. the following day, he had succeeded in his mission, and on the 19th he was reinforced with the 16th Lancers and additional guns. With his increased force he was to cover the advance of the approaching battering train, and communicate with the garrison of Ludhiana, which was being threatened by a Sikh force at Phillaur. Picking up H.M.53rd Foot on the way, Smith advanced towards Ludhiana.

On the way he received intelligence that the Sikhs had crossed the Sutlej and occupied the fort at Badowal as well as one a little further south at Gangrana. He had no wish to present his flanks to these two forces and determined to move from Jagraon to Ludhiana by marching between Badowal and the Sutlej. Nearing Badowal at dawn on 21 January he was disconcerted to hear that a Sikh army of some 10,000 men with 40 guns under Ranjur Singh was within two miles of him. Since he only had three cavalry regiments, four infantry battalions and eighteen guns, Smith decided to try to pass Ranjur Singh by swinging off the road and moving South of Badowal. Although he fired on the British column, Ranjur Singh made no attempt to close, contenting himself with picking up stragglers and capturing the baggage.

Reaching Ludhiana, Smith took command of Godby's brigade, there as a garrison, and after resting the tired troops prepared to attack Ranjur Singh. The Sikhs had no wish to cross bayonets with the British just then, and withdrew northwards towards the Sutlej, where they were reinforced. Smith marched back to Badowal where he was joined by the other brigade in his division, more cavalry and extra guns. By the 26 January, Smith's force now numbered 12,000 men with 32 guns.

Allowing his men a day's rest, at dawn on 28 January the army marched north-westwards to cut off Ranjur Singh who with 20,000 men and 67 guns, was reported to be contemplating a move on Jagraon: '...(M)y order of advance was - the Cavalry in front, in contiguous columns of squadrons of regiments, two troops of horse artillery in the intervals of brigades; the infantry in contiguous columns of brigades at intervals of deploying distance; artillery in the intervals, followed by two 8-inch howitzers on travelling carriages....' Wargamers might like to note the precision and system by which Smith obviously deployed his units, and did not just 'get 'em out the box and plonk 'em on the table!'

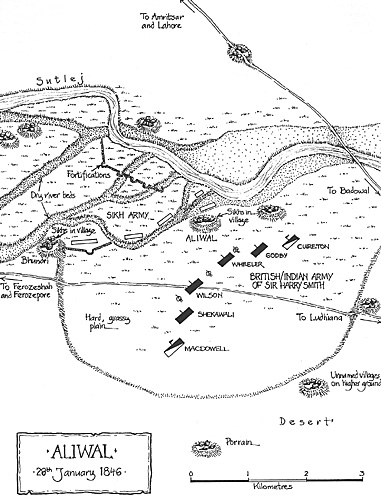

For some 10 miles, the march was over sandy semi-desert. At roughly 8:30, as Smith was approaching Aliwal, a spy came in and reported that the Sikhs had indeed vacated their entrenchments and were marching on Jagraon. If true, they had not got very far. As the British army drew nearer, and Smith reached the top of the sand ridge near Porrain, the Sikhs were seen to be taking up a lightly entrenched position above a dry river bed. Their left rested on the hastily fortified Aliwal village and their right on Bhundri, which was screened by a thin grove of trees. The ridge sloped gently down to a hard grassy plain, totally unobstructed, and thus eminently suitable for all arms.

'I immediately deployed the cavalry into line and moved on. As I neared the enemy I ordered the cavalry to take ground to the right and left by brigades; thus displaying the heads of the infantry columns, and, as they reached the hard ground I directed them to deploy into line. After deployment, I observed the enemy's left to outflank me, I therefore broke into open column and took ground to my right. When I had gained sufficient ground, the troops wheeled into line. These manoeuvres were performed with the celerity and precision of the most correct field day.'

Pearman was attached to Alexander's 3rd Troop of the 2nd Brigade of Bengal Horse Artillery to replace casualties suffered at Badowal. The Troop was assigned to support MacDowell's cavalry on the left. In Pearman's descriptive phrase 'We came to a halt, and the infantry and foot artillery began to get into a line, spreading out like a lady's fan.'

The British position was thus: In front rank, Hick's brigade on the right, Wheeler's in the centre and Wilson's on the left, and the artillery deployed along the front. Echeloned behind were Godby's brigade on the right and the Shekawali brigade on the left; whilst at the rear were Stedman's cavalry echeloned to the right and MacDowell's to the left. The whole formation was thus an inverted and flattened 'V' with the point towards the Sikhs and the cavalry as the bottom of the two strokes. At about 10:00, when the line had got to within 700 yards of the entrenchments, the Sikh guns opened up and Smith halted. He carried out a final reconnaissance, especially trying to pick out the artillery.

The prime weakness of the Sikh position should be readily apparent. By taking up a position with their backs to the river, crossable only by a bridge of boats and a nearby ford, a disruption of their front anywhere would push them back into it. Smith therefore extended his right by bringing up Godby. After some thirty minutes, whilst the British artillery advanced and unlimbered, Godby and Hicks were launched into an attack against Aliwal. It would appear that this village was defended by irregulars from amongst the hill tribes, for the two brigades cleared it at the rush capturing two heavy guns in the process.

Seeing the success, Smith ordered Wheeler and Wilson to attack the Sikh centre and left, and the horse artillery pushed forward until they were firing canister at 200 yards. This suppressed the defence sufficiently for Wheeler to get into the entrenchments and capture the guns. With his left also pushed back behind Aliwal, Ranjur Singh appreciated that he was in danger of being cut off from the Sutlej, so he ordered up a large body of cavalry. This arm was never one of the Sikh's strong points, being mostly irregular, and Stedman was able to break it up with little difficulty.

With Godby sweeping along the river bank, Ranjur Singh tried to hold Bhundri and attempt to wheel his left back. To cover this another body of Sikh cavalry was called forward. MacDowell countered this by ordering two squadrons, one of the 3rd Light Cavalry and the other Captain Bere's of the 16th Lancers, to disperse them. The Light Cavalry hesitated, but the 16th charged, broke the Sikh horse and pursued them towards the river. When the Lancers tried to rally back however, they found their way blocked by squares or triangles formed by units of Sikh regular infantry.

Supported by another squadron under Captain Fyler charging in from the outside, they rode over and through the mass, but suffered close to 30% casualties whilst doing so. The fighting was hand to hand and savage. Once the Sikhs had fired their only volley, they dropped their muskets and took up their shields and tulwars. If they could not get at the riders, they would attempt to bring down the horse. Once a lancer was on the ground, '...they rushed at him and never ceased hacking at them, till they had literally severed them all to pieces with their tulwars, which were like razors.'

Meanwhile, the right wing of the regiment, two squadrons under Major Smyth were sent to charge an entrenched battery. It was at roughly this time that Pearman '...looked to our left and saw the 16th Lancers coming on at a trot, then a gallop. I took of my cap and hollered out: "The first charge of British Lancers!"'. Smyth's two squadrons charged 'a battalion of the enemy's infantry and a battery of 9 and 12 pounder guns At the trumpet note to trot, off we went. "Now,", said Major Smyth, "I am going to give the word to charge, three cheers for the Queen." There was a terrific burst of cheering in reply and down we swept upon the guns. Very soon they were in our possession.

A more exciting job followed. We had to charge a square of infantry. At them we went, the bullets flying round like a hailstorm. Right in front of us was a big sergeant, Harry Newsome. He was mounted on a grey charger, and with a shout of "Hullo boys, here goes for death or a commission", forced his horse right over the front rank of kneeling men, bristling with bayonet. As Newsome dashed forward he leant over and grasped one of the enemy's standards but fell from his horse pierced by 19 bayonet wounds.

Into the gap made by Newsome we dashed, but they made fearful havoc among us. When we got out on the other side of the square our troop had lost both lieutenants, the cornet, troop-sergeant major, and two sergeants. I was the only sergeant left. Some of the men shouted, "Bill, you've got command, they're all down". Back we went through the disorganised square, the Sikhs peppering us from all directions. We retired to our own line. As we passed the General he shouted "Well done, 16th. You have covered yourselves with glory." Then noticing that no officers were with C Troop, Sir Harry Smith enquired, "Where are your officers?" "All down", I replied. "Then", said the General, "go and join the left wing, under Major (sic) Bere."'

Bere launched another charge which broke open another square, then the whole regiment pushed forward to allow H.M. 53rd Foot to clear Bhundri. Behind the village was a dry watercourse into which some thousand Sikhs had fallen back, threatening to be an obstacle to any further advance. A flanking charge by the 30th Bengal Native Infantry dislodged them and forced them out into the open where twelve guns mowed them down at a range of 300 yards. With the last resistance shattered, the Sikhs began withdrawing towards their bridge of boats over the Sutlej. The retreat soon degenerated into a rout, helped by the two 8 inch howitzers bringing fire down on the bridge. Of the 67 guns that the Sikhs deployed, only six reached the river. Two stuck in the mud and were spiked, two went down in quicksand and only the last two reached the far bank, only to be spiked by pursuing troops. For some two hours, the Sikhs tried to re-organise on the north bank, continually under fire from the British batteries, until at about 5:20 they withdrew out of range.

The battle had cost the British 589 men, of whom 245 were cavalry. Of this total 141 were from the 16th Lancers, i.e. just over 25% of the casualties were from one unit, which itself had suffered 25% casualties. The Sikhs had suffered some 3,000 casualties, all their stores and camp, as well as 67 guns, the disposal of which was to perplex Sir Harry Smith, which he solved by convoying them to Ludhiana. For the 16th Lancers, Aliwal was to give birth to a regimental tradition.

Too exhausted to do much more than rest their horses and feed themselves, the Scarlet Lancers left their lances stacked overnight. In the morning, the blood with which the lance pennons had been saturated had dried them rigid, so that it became a tradition to crimp the pennons in memory of the battle. Even today (I believe), the lances that stand outside the regimental headquarters are crimped.

At first glance, it would seem that the decision to form British Lancer regiments had been vindicated, even at a high cost, but an examination needs to be made. The tasks given to the 16th were not those that would ordinarily be given to light cavalry. Attacking positions would ordinarily be the province of heavy cavalry. It is worth remembering that British heavy cavalry would not be employed in India until the Sepoy Rebellion. It is perhaps understandable therefore that the European-horsed British light cavalry was called upon to carry out attacks that would not be considered on a Continental battlefield.

Equally, when the series of wars broke out on 1864 that was to lead to German unification, the Uhlan regiments were considered to be heavy battle cavalry and put in kuwassier formations. '• also appears that the lance was not found to be such an efficient weapon after all, for Pearman reported seeing '...such cutting and stabbing I never saw before or since.', which indicates that some Lancers at least dropped their main weapon and used their sabres.

Indeed, Captain Nolan went so far as to write that it was 'well known that, in battle, lancers generally throw them away, and take to their swords. I never spoke with an English lancer who had been engaged in the late Sikh wars that did not declare the lance to be a useless tool, and a great encumbrance in close conflict.' If this is so, it would tend to validate the changes observed in Polish Lancer regiments during the Napoleonic War, when it was urged that the second echelon be sabre armed. (Wargamers might like to consider the idea that lancers only count as lancers for the first melee in which they are involved.)

That said however, the Battle of Aliwal has been justly described as 'the battle without a mistake.' Sir Harry Smith was justly proud of his victory. When he was awarded his baronetcy, he took it as 'of Aliwal'. Just as there are the towns of Harrismith and Ladysmith in South Africa, named in honour of both him and his wife, so there is an Aliwal in commemoration of his most impressive victory.

The Battle of Aliwal 28th January, 1846

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 15 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1994 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com