This stereotype is misleading,

however, since Napoleon was actually very

interested in fortresses and siegecraft. As a

gunner and the victor of Toulon, after all,

he was fully conversant with the scientific

aspects. In his 'classic' campaigns of

invasion such as Austerlitz or Jena,

moreover, he made it a rule never to move

anywhere without having a strong

fortification at least once in every four

days' march along his line of

communication (or Route de l'Armee.

These fortifications had many roles: as

centres to control conquered areas or to

collect supplies and convoys and defend

them against enemy raids. They would also

be rallying points for reinforcements

moving up to the front, who would

themselves normally provide the garrisons

without taking soldiers directly out of the

front line. And if the worst should happen,

these forts would provide rallying points

and depots for Napoleon's retreating army

if it were defeated.

In the case of Wellington, however,

the general impression is that he was still

an eighteenth century type of commander --

taking everything very slowly and

carefully, and placing great importance on

siege warfare - but actually this too is very

far from the truth. Wellington was in reality

a very mobile and aggressive commander,

and often a gambler (as Michael Glover,

among others, has ably argued in his

numerous Peninsular histories [1]

), Wellington was excellent at seizing

fleeting opportunities to make an attack,

which was an art he had learned in his

Indian battles at Assaye and Argaum, and

then carried forward to Oporto (1809),

Salamanca (1812) and Vittoria (1813).

It was only in the period between

Oporto and Salamanca -- or more

accurately from Talavera, which was a

failed offensive that followed soon after

Oporto - that he was forced to adopt a

more defensive posture for the security of

Portugal, which has been called

Wellington's 'Cautious System'. It is this

period of almost three years in 1809-11

which has branded him as a defensive

general in many people's eyes.

In fact, however, even during this

'cautious' phase he made several attacks on

the French fortresses covering the exits

from Portugal -- usually Badajoz -- but it

was largely because he failed to win these

sieges before 1812 that he was unable to

burst out into the Spanish plains for more

adventurous manoeuvres.

The trouble was that Wellington

was really not much good at siege warfare.

It was perhaps his greatest weakness as a

commander. Just as he had learned the

power of a sudden offensive in the field, in India, he had also found in that theatre -- at

the sieges of Dummul, Arrakerry,

Armednuggur and Gawilghur -- that any

Indian fortress could be carried very

quickly by a sudden storming.

Unfortunately the same was not

true against the scientific French, and these

'colonial style' assaults often bounced off

carefully-prepared defences manned by

determined troops with knowledgeable commanders.

In the Peninsula there were always

grave difficulties of logistics and these

became acute whenever it was necessary to

collect the vast mass of materiel, artillery

and ammunition required for a siege. The

navy might quibble over the release of its

guns for land service; the roads would be

exceptionally tested by the exceptional

demands of the siege train, and considerable

powers of foresight would be required to

predict the probable need for such items as

shovels, gabions, scaling ladders or building

timber. There was also a sorry shortage

of trained engineers, with the Corps of

Sappers and Miners being created only

towards the end of the war, after the Royal

Military Artificers had been shown to be

inadequate in both numbers and skills

during the important earlier sieges. Engineer

officers had a distressing habit of being hit

by enemy fire at the very start of digging

operations or, in the case of the great

Badajoz storming, at the start of the assault

they were intended to direct throughout its

duration.

[2]

In these circumstances Wellington

often found that his strategic needs were

too pressing to wait for the realistic speed

of these siege operations, so he would be

tempted to insist on dangerous haste. This

in turn implied a willingness to expend the

lives of his troops in the interests of a

quick success, and there were some horrible

scenes of carnage in the ditches at the base

of ill-prepared breaches.

Against this, it may perhaps be

argued that Wellington made constant

subconscious calculations about just how

many lives he could afford to gamble, in

order to win an important fortress in good

time. No one can deny that he was a

numerate general, just as he was certainly

an experienced one.

Thus although he wept openly at

the horrific scale of casualties in the

eventual capture of Badajoz, he surely also

realised in that moment that the plains of

Leon lay open to him as a direct result of

the sacrifice. The capture of Badajoz

opened the road to Madrid for the first

time since the strategic defeat of the

Talavera campaign almost three years

earlier, and although the victory of

Salamanca would cost a further 5.200 allied

casualties, it surely more than made up for

the relative balance of losses as between

the allies and the French.

If it is true that Wellington really

did base his gambles in siegecraft upon

some basis of subconsciously-perceived

'vital statistics', then it would surely be

interesting to find out just what those

statistics might have been.

In an attempt to find out, I looked

up the classic Journal of Sieges in Spain by

Sir John T Jones.' Within its pages there

are details of all the British sieges between

1811 and 1814, although not quite all of

them were Wellington's. Jones' selection

includes Bergen op Zoom in the

Netherlands, one in southern Italy and a

couple on Walcheren island, as well as the

French attack on Tarifa, near Gibraltar,

which was the only Peninsular siege where

the British (as opposed to their Spanish

allies) were the defenders. However, I don't

think it is illegitimate to include these 'non

Wellington' cases, since their general

conditions seem to have been very

consistent with what Wellington himself

was doing in his attacks on fortresses.

From these statistics we can see

just how attractive it must have been to lay

siege to a fortress, insofar as almost 40% of

the forts attacked were pretty small and

weak, and of these almost 80% surrendered

before they were stormed at all.(See Table

1) Of the remaining forts that were 'big', a

third was attacked by an army which seems

to have been of adequate strength and fully

prepared.' Apart from their superior

artillery and engineer assets, these could

normally mount three or four assault

columns in the final storming, which was

enough to swamp the defences in 80% of

cases.

The real problem comes when we

turn to the 9 cases when big fortresses were

attacked by small armies. Wellington is

shown in his worst light whenever this

happened, and in the first attempt against

Badajoz in May 1811 he was so slow to

develop a convincing attack that Soult's

relieving army was able to arrive before a

storming could even be mounted. At

Pampluna in July 1813 Wellington decided

on a blockade rather than any sort of siege,

although he betrayed his frustration by

issuing the most blood-curdling instructions

that his Spanish allies should hang the

entire garrison if they should ever manage

to catch 'em.

Soon after this Wellington's

frustration came to boiling point when

Graham's ill-prepared first effort to storm

San Sebastian ended ignominiously, just at

the moment when Marshal Soult (once

again!) was dealing a shrewd surprise blow

across the inland mountains.

Overall, only in 22% of the 'Small

Army vs Big Fort' attacks was the fort

finally captured, which is an almost

diametrically opposite to the result from

the 80% success of 'Adequate Army vs Big

Fort' attacks. The need for numerous attack

fronts is certainly confirmed (See Table 2)

when we analyse the stormings in terms of

the number of assault columns used in each

case.

Thus we only have 2 examples of

stormings against small forts but, it is

notable that one (at Almaraz) was

successful when it used 3 columns -

thereby splitting the defender's attention

and fire while the other (at Tarifa) failed in

a single column. The same is true with the

'big forts attacked by adequate armies',

where 80% of the assaults were in 3 or 4

columns - although admittedly the one

attack in a single column (at San Sebastian)

was also a success. Equally the generally unsuccessful cases of 'big

forts attacked by small armies' were all in

only one or two columns, and showed a

poor record of success.

Let us consider the success of each

individual column .(See Table 3: Success of

each Column): The very difficult nature of

actual stormings is shown by the fact that

over half of them ended in total failure, and

less than 30% of the assaults were

'completely' successful against big forts.

Even in multiple assaults which together

led to the capture of the fort, the majority

of the columns might fail and even, as

'Feints', may have been excpected to fail.

Finally, let's look at the casualties

suffered within each of the storming

columns. Contrary to our expectations, we

find that the least successful assaults

tended to suffer relatively light casualties,

whereas the more effective attacks were

often by far the bloodiest. Perhaps this

shows that a failed attack tended to be over

quickly although in several cases, such as

the second siege of Badajoz, the storming

party stayed in the ditch for a full hour,

trying to find a viable escalade, before it

retired. It was certainly the most

determined troops who pressed on into

danger and paid the price, and particularly

in the case of 'partial' successes, which

tended to be bloodier than 'complete' ones.

Storming Through the Peninsula

Siege warfare is a rather

neglected part of Napoleonic studies, since

it is generally assumed that the great

Emperor had 'revolutionised' the art of war

to the extent that sieges were no longer

important. In 1800 he had scornfully by-passed Fort Bard, on the Italian frontier, in

order to strike deep into the heart of the

country and fight a decisive battle at

Marengo. If the campaign had been fought

by some of his eighteenth century

predecessors, it would doubtless have

settled down into a long siege on the

frontier, and stayed there.

Siege warfare is a rather

neglected part of Napoleonic studies, since

it is generally assumed that the great

Emperor had 'revolutionised' the art of war

to the extent that sieges were no longer

important. In 1800 he had scornfully by-passed Fort Bard, on the Italian frontier, in

order to strike deep into the heart of the

country and fight a decisive battle at

Marengo. If the campaign had been fought

by some of his eighteenth century

predecessors, it would doubtless have

settled down into a long siege on the

frontier, and stayed there.

The Role of Siege in Napoleonic Warfare The MYTH The REALITY Napoleon's deep invasions removed the need for fortresses. Napoleon always cemented his L of C with fortresses. The 'mobile' French didn't need to run sieges in either attack or defence.

They often did run them, and were very good at them. The British had a "plodding 18th century-style" army, ie were good at sieges.

Wellington, at least, was poor in siege warfare (= more like the French image!).

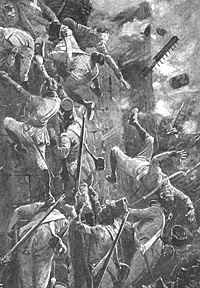

The French used the column but the British used the line (in tactics). Wellington used big columns repeatedly in his sieges, but the French engineered in lines.  The third Badajoz siege in April 1812,

in particular, is notorious less for the very

heavy toll of 1,300 casualties lost during its

preliminary engineering phase than for the

3,700 casualties suffered in the final

storming. This total of 5,000 men -- the

equivalent to an entire Division -- is the

type of loss to be expected in a major

battle; and after Talavera it was in fact the

second longest butcher's bill that

Wellington had ever suffered up to that

point. [3]

The third Badajoz siege in April 1812,

in particular, is notorious less for the very

heavy toll of 1,300 casualties lost during its

preliminary engineering phase than for the

3,700 casualties suffered in the final

storming. This total of 5,000 men -- the

equivalent to an entire Division -- is the

type of loss to be expected in a major

battle; and after Talavera it was in fact the

second longest butcher's bill that

Wellington had ever suffered up to that

point. [3]

Hence the British can scarcely be

faulted in the cases of attacks against small

forts, or against big forts attacked by

adequate armies - i.e. slightly more than

a half of the total - and in fact the only 'big'

fortress which ultimately survived attack

by what I have called an 'adequate' army

was Bergen op Zoom (ie Not one of

Wellington's sieges); whereas the only

'small' fortress which survived attack was

Tarifa (when it was the French attacking a

British garrison). So far so good the

casualties in these assaults may have been

horrific, and far more than Vauban would

have been happy to accept - but the final

strategic success represented by the

capture of the fort surely goes a long way

to absolve Wellington of serious blame.

Hence the British can scarcely be

faulted in the cases of attacks against small

forts, or against big forts attacked by

adequate armies - i.e. slightly more than

a half of the total - and in fact the only 'big'

fortress which ultimately survived attack

by what I have called an 'adequate' army

was Bergen op Zoom (ie Not one of

Wellington's sieges); whereas the only

'small' fortress which survived attack was

Tarifa (when it was the French attacking a

British garrison). So far so good the

casualties in these assaults may have been

horrific, and far more than Vauban would

have been happy to accept - but the final

strategic success represented by the

capture of the fort surely goes a long way

to absolve Wellington of serious blame.

NOTES

[1] e.g. his

Wellington as a Military Commander

(Batsford, London 1968).

[2] The

Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo, and the three sieges of

Badajoz, are covered in Oman's History of the

Peninsular War, Vol IV, pp.247, 315, 404.,,

and Vol V, pp. 157, 244.

[3] See the

table of losses in all Wellington's battles

presented in the Appendix of Paddy Griffith, ed.,

Wellington - Commander (Bird and the

V&A, London 1984).

[4] First

published 1813, but soon updated to

include the end of the war in 1814.

My own analysis of the statistics that can be

extracted from Jones first appeared in Empires,

Eagles & Lions magazine #97, Nov-Dec

1986, and the present article is based largely on that.

[5] I have

found no scientific definition for what constitutes

an 'adequate' army for the attack of a large fortress,

since any army with a strength over around

30,000 men will probably have enough troops.

More important for the army's adequacy must be

less easily-quantifiable aspects such as adequate

engineer and artillery resources. I have been able

to assess these only an a subjective basis,

although I am reassured to find that my

assessment generally seems consistent with the

number of assault columns finally used.

Siege Operations in the Napoleonic Wars

Table 1: Small Forts are Easy Prey and Big Forts Can Be Taken

Table 2: Number of Columns in Each Attack

Table 3: Success of Each Column Against a Big Fort

Peninsula Storming The Game

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 14 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1994 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com