When I first began writing this article in early 1992, the fighting in Croatia had almost ended and the slaughter in Bosnia was about to start. Already to those who knew the history of the area, it was quite clear that the failure to stop the war in Croatia would only encourage the ancient rivalries of the area. It was only with the Bosnian crisis that the world finally realised that the roots of all the fighting in the area go back further than the Second World War. In particular, events during the Napoleonic period have many echoes in the current situation. The political interests of surrounding nations and the network of allegiances which threatens to engulf the whole area in war have changed very little in the intervening 200 years and neither has the warlike disposition of the peoples of the area. The Napoleonic period also marks the consolidation of perhaps the most obvious line of fracture: the southern borders of Croatia, scene of much of the the preBosnia fighting between Serbs and Croats. As Lord Owen acknowledged, maintaining the ancient borders of Croatia would have done much to stop the land-grab which followed in Bosnia.

The Historical Background

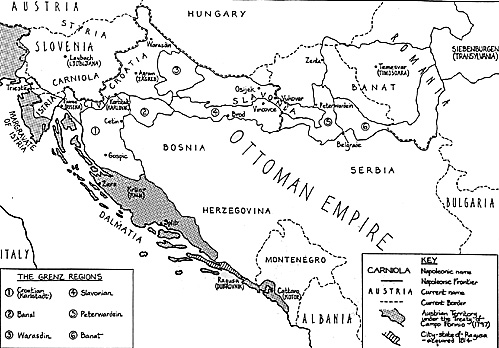

Historic Croatia was originally centred in what is now western Bosnia and suffered severely at the hands of the l4th century Venetians (to whom they lost Dalmatia), and the Turks, who swept across the Balkans as far as the gates of Vienna in the 16th century. By various successful marriage agreements, the Habsburgs had acquired Carniola and the County of Istria in the 14th century, and in 1526, large areas of central Europe -Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia and Croatia. However, by this time, only a fragment of Hungary and Croatia was not under Turkish rule - thus these acquisitions brought the Habsburgs right up against the Turks along a line running from western Croatia across northeastern Hungary to Silesia,(I). Having itself been established as a bulwark against marauding Magyars and Slavs, Austria found itself acting as the frontier of Christendom against the infidel Turk and the rudiments of an organised defended frontier began to take shape along this line under direct military control. After 150 years, the defences were breached by the Turks, who in 1683 laid siege to Vienna for the second time, but they had overstretched themselves. Saved by the forces of the Holy League, the Habsburgs drove out across the Hungarian plain - to the south, all the area up to the rivers Danube and Save was cleared as far as the Carpathian mountains in modern-day central Romania.

With the advance to the Save, it was possible to demilitarise much of the old military frontier area, although the Crown retained southern Croatia and the new border areas as far as the Danube/Save junction,(the eastern end of Peterwardein) - the other reconquered lands were placed under the civilian control of the noble assemblies of Croatia (the Sabor), and Hungary (the Diet). The original Habsburg Croatia was thus the former southern end of the old frontier, (Warasdin and Karlstadt Districts), plus the later-named Civil Croatia.

Habsburg conquest of these areas and Siebenburgen (Transylvania), was recognised by the Turks at the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The area of the Banat of Temesvar (now the Vojvodina part of Serbia and eastern Romania), was overrun in 1718 and briefly, areas of northern Serbia were taken (Peace of Passarowitz 1718).

Shortly before the accession of Empress Maria Theresa (1740 - 1780), the territories in Serbia were re-ceded to the Turks and the frontier with the Ottoman Empire came to rest along the line which now separates northern Croatia and the Vojvodina from the rest of former Jugoslavia. Along the Adriatic coast, the Venetians continued to hold Dalmatia and the Turks held on to the area around the great fortress of Cetin until 179 1, when the Austrians captured it in the last great clash with the Ottomans - this area continues to have a large Moslem population (2).

As compensation for the non-recovery of much of historic Croatia, Slavonia (3), was joined to Croatia under the rule of the Ban (Viceroy) of Croatia. Croatia/Slavonia and the border area,(now formally known as the Military Frontier or 'Grenz'), now extended eastwards to the Theiss river, where it met the western border of the Banat. The Banat of Temesvar (4), was initially wholly under the military control of the Crown under another Ban, but in 1777, Maria Theresa agreed to the liquidation of the military establishment in most of the province, so that only the southern and eastern parts became part of the Grenz system.

Beyond the Banat in what is now central Romania was Siebenburgen - this rugged mountainous area, which had enjoyed some autonomy under the Turks, had always existed in a semi-paramilitary state and whilst part of the frontier, was not therefore part of the true Grenz (and is therefore beyond this article's scope).

Thereafter, Imperial policy seems to have been based on Maria Theresa's maxim that she was not interested in expansion into "a lot of barren mountains and feverish swamps inhabited by unreliable Greeks" (that is Orthodox Christians - ie:Serbs) (5).

The Demographic Background

The devastation wrought by the wars with the Turks had virtually emptied large areas of the reconquered lands, such that space was available for new settlers. However, the Balkans had long been an area of mass migration and the consequent admixture of population. The Serbs and Croats had their original roots in what has later become known as the 'southern Slavs',but the division between them appears to date from the separation of the Orthodox Church from the Catholics in the 11th century. By the early 17th century, as a rule of thumb the Croats were the Catholics and the Serbs were the Orthodox.

Closely connected to Catholic Hungary, the Croats had been pushed out of Bosnia into what was now 'rump Croatia' around Agram,(now Zagreb) and the western end of the Grenz - there were gradually scarcer outposts further east in Slavonia and Bosnia, but by 1700, the Croats were mostly inside the Habsburg Empire. The Serbs however had largely remained in place. Many, especially in Bosnia, converted to Islam to preserve their land and goods, while others had remained Orthodox; some had also migrated north into Slavonia and the Banat under Turkish pressure(6) and a sizeable group, which converted to Catholicism, reached the southern part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The mainly Magyar population of Hungary also extended south into the Banat itself. Refugees from the eastern Balkans and the area which is now southern Romania had found their way into the eastern Banat - largely Bulgars and Romanians, they were collectively known as the Vlach,(later Wallachians).

After the reconquest, large scale immigration from both Germany and the Christian, (ie: mainly Orthodox), parts of the Balkans was encouraged, with the extra incentives of freedom from serfdom and land for those coming to the Frontier. The Germans were particularly encouraged to settle in the Banat to counter-balance the northward movement of Serbs and Vlach, the bulk of whose compatriots were always outside the Austrian Empire.

The areas of Carniola and southern Styria were largely Slovene, with the population of Istria being a mixture of Italians and Slovenes.

By 1780, by these measures, the population of the Grenz had been raised to about 700,000, of whom 360,000 were Croat, 240,000 Serb, 30,000 German and about 80,000 Romanians and others. Within Civilian Croatia and Slavonia, there were 465,000 Croats, 165,000 Serbs, 5,000 Germans and a few thousand Italians, Magyars and Slovenes.

More importantly, the distribution of population along the Grenz was not even. Civilian Croatia was almost solidly Croat, with most of the Germans in the towns, whereas civilian Slavonia was mostly Serb. Within the Grenz area, the Croats dominated the Karlstadt District, although the southernmost area, the Licca, on the Dalmatian border, was almost all Serb. Slavonia was predominantly Serb and a large Serb minority was mixed with the majority Croat population of Warasdin. Within the Banal region (7),there was about a 50:50 split, and as above, the Banat was a mixture of a number of groups.

Economic Conditions

The economy of the Grenz was based on subsistence farming usually of cattle,and basic crops, with some cereals in the better areas - mainly in the central Grenz, as the soil in the Banat and more mountainous west was poor to variable. Its population of almost all free farmers in farms based on the traditional Slav 'Zadruga', a multifamily household of near-relatives was thinly spread out in a patchwork of small settlements mixed up between Serbs and Croats -a situation which remained the same until the recent troubles. Imperial policy was to encourage closer groupings to improve the defences against marauding Bosnian bands and Turks, but few settlements were larger than a hamlet. The few towns of the area were mainly in the Civilian divisions or close thereto.

The average Grenzer's home was little more than a shack, many without chimneys and windows, even in the more prosperous areas. The peasant soldier had to be a tough self-reliant character to survive in an area of very poor communications and medical provision of about 7 doctors per 100,000 of population. Frequent famines were a particular problem, both for the maintenance of the population and the morale of Grenzers on field service. Their wretched conditions are perhaps best summed up by a French soldier at Austerlitz, who remarked that the Grenzer could be heard "intoning one of those dirge-like and melancholy songs of theirs"(8).

Only in the Banat were conditions generally better, as German colonists had brought some industry and commerce. The Germans also tended to dominate the towns right across the area,where there were small groups of artisans, clergy and craftsmen's Guilds, together with the homes of senior Grenzer officers (9).

The Organisation of the Grenz

As the Crown owned all the Grenz land, the farmers held it in return for military service to the Emperor - as a result, Grenzer officers were amongst the most loyal subjects of the Crown. Initially organised as a militia keeping a watchful eye on the border, the possibilities for using these cheap and readily available troops in the Empire's other wars did not go unnoticed for long.

Aside from a short period from 1782 to 1800, when there was partial civilian rule, the Grenz was always under military administration. It was divided into the Karlstadt, Banal, Warasdin, Slavonian (inc. Peterwardein), and Banat Districts, within which the administrative unit was the Regiment (this was not the tactical unit, which was the battalion).

All males in the Grenz were added to the Regiment's muster-roll at birth and were actually liable for military service between the ages of 16 and 60. Each Zadruga (officially 'Hauscommunion'), had to supply at least one suitable male (according to its size), and inheritance of the tenancy was dependent on fulfilment of this obligation(IO). The Grenz system supplied the Crown with a cheap source of manpower, estimated by Major-General Klein in 1803 to cost only 20% of the equivalent regular troops (11) and large quantities of it "This (Zadruga) system is the cornerstone on which the military force rests. Without this system, in a region, which in its population would, by comparison with the Hereditary German provinces, hardly raise three regiments, it would not be possible to put seventeen regiments into the field" (Stapfer, Commentary on the 1807 Basic Law) (12).

Within the Regiments, the military commander was responsible for the military and civilian administration and each regiment had a staff of about 230 at headquarters, responsible for civilian work. The whole area was administered for the Crown by the military-political body,the Hofkriegsrat (in conjunction with the Ban of Croatia in the Banal District).

The number of Regiments within a District varied with the population, although battalion sizes were standardised under Maria Theresa. By 1790,the division was as follows (bases in brackets):

- Karlstadt: 4: Liccaner (Gospic), Ottocaner (Ottocac), Oguliner (Ogulin),Szluiner (Karlstadt);

Warasdin: 2: Warasdiner-Creuzer (St. Belovar), WarasdinerSt.Georger (St. Belovar);(13)

Slavonia: 3: Broder (Vincovce), Gradiscaner (Neugradisca), Peterwardeiner(Mitrowitz);

Banal: 2: 1st Banal (Glina), 2nd Banal (Petrinia);

Banat: 2: Deutschbanater (Pancsova), Wallachisch-Illyrisches (Karansebes).

The Karlstadt and Warasdin Districts had already been been joined together as the 'Croatian General Command' with its HQ in Agram.

Unlike the regular army, each regiment retained its regional name and didn't change with the colonel (Inhaber). The position in the Banat was only differentiated by a policy of recruiting separately among the German,(mainly Catholic), settlers and the Romanian/Serb (mainly Orthodox), population ('Illyrian'was an alternative name for Serbian).

The system was also used in Siebenburgen region, which provided 4 regiments - 2 from the Saxon-Szeckler community and 2 from the Vlach.

Under Joseph II, (1780-1790), the available peasant-farmers were divided into 'enrolled' and 'supernumerary' - the latter not serving with the colours the exact proportion depending on military requirements, although obviously the more fit and able were in the former group. Imperial policy was always juggling with the conflicting demands of providing the maximum number of troops, while maintaining sufficient manpower in the Grenz to ensure sufficient agricultural production to support the population.

Of the enrolled men, peacetime operations necessitated dividing them into three groups of approximately equal size for the functions of

- a) guarding the frontier

b) providing a ready reserve, and

c) local defence of each group of settlements.

In wartime, the first two categories would provide the field battalions , while the third provided the local defence - the Landes-Defences Divisions and the Cordon troops (the latter, just keeping watch on the border, consisted of troops unfit for field service).

In order to maintain a level of training without damaging the agricultural economy, the Grenzer were called in on a rota basis for training and guard duties, although demands were kept to a minimum during sowing and harvesting.

Peacetime tasks did not just mean keeping watch for Turkish and Bosnian incursions - troops had to check cross-border trade, control refugee entry, and even in 1770, had to maintain a Sanitatskordon to protect Europe against the threatened spread of bubonic plague. In this last emergency, the entire Grenz force was called out to erect blockhouses along more than 1,000 miles of frontier, even into the inhospitable Carpathian mountains.

Other Pressures

The constant worry for the Catholic Habsburgs was the steady growth of Orthodox populations of Serbs and Vlach within the Empire's boundaries, especially as the ravages of war and famine required measures to maintain the Grenz population. The Croats, despite their differences with the Serbs, had close links to the Slav population across the border - above all of trade and ethnic grouping. Naturally, political events in the Ottoman Empire were of great interest - not least because of potential pressure on land from refugees.

Nonetheless, the Habsburgs periodically engaged in policies aimed at converting Serbs to Catholicism. Their greatest worry was the natural inclination of the Serbs to look to the Orthodox Russians as their true protectors. Consequently, there was discrimination against Serb officers, who were not permitted command above battalion level. Only briefly, under Leopold 11 (179092), did the Serbs come near to a separate identity under the Habsburgs, when an 'Illyrian Chancellry' (Regional Affairs office within the central government in Vienna), existed between 1791 and 1792. It was however only a counterweight to Croat and Hungarian demands for greater autonomy once that subsided, the Chancellry was abolished.

Right from the inception of the Grenz, the noble assemblies of Hungary and Croatia had attempted to gain control of these areas. The threat to the Grenzer of a return to near-serf status was obvious - and the central government exploited these fears to the full.

Notes

1) The Kingdom of Hungary was almost 50% larger than today's state and reached as far as Slavonia and the Grenz;

2) An important fortress, which featured in the recent fighting in Croatia. It is adjacent to the Bosnian Moslem enclave around Bihac;

3) Never part of historic Croatia, this area had a large Serb majority and its central area around Osijek/Vukovar/Vincovce saw the worst fighting in 1991, being right on the Serbia/Croatia border;

4) Now known as Timosoara, this is the centre of the Hungarian minority in modem Romania and was the seat of the 1989 rebellion against Caucescu;

5) CA Macartney, 'The Habsburg Empire 1790-1918'(1969) p.117 -the standard work in English on the history and conditions of the empire;

6) A Turkish counter-stroke around Belgrade in 1693 caused a massive exodus north;

7) 'Banal' means ruled by the Ban, (of Croatia), who retained control of civilian affairs in the area and nominal command of the regiments;

8) C. Duffy, 'Austerlitz 1805' (1977) p. 146;

9) Town residents were generally exempt from Grenzer obligations as they didn't hold land, although many officers had residences there. A 'Daily Telegraph' report of 2.1.1992 commented that 80% of those doing the fighting in Croatia were farmers.

10) J. Zimmerman 'Militarverwaltung und Heeresaufbringung in Oesterreich his 1806' p.39;

11) G. Rothenberg 'The Military Border in Croatia 1740-1881(1966) - the fundamental history of the Grenz - p.95

12) Zimmerman, p.44;

13) Something of an anomaly, the Warasdin District was a remnant of the old frontier, where it turned north across Hungary. Warasdin itself was outside the District, as part had been demilitarised. The retention of the name demonstrates the lack of sizeable settlements in the area.

More Jugoslavia

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #11 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1992 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com