The men, traveling so many months in their ships, with so little to do, must by now be filled with the excitement of anticipation for the next power maneuver: they must slow down when at the proper location and distance from Mars; failing to do this, they would simply sweep through a hyperbolic arc and continue outwards into interplanetary space.

The very large spherical tanks that provided the fuel for earth escape are now discarded in preparation for the slowing down maneuver. It is necessary to reduce the weight of the ships before each power maneuver in order to maintain as close to an ideal mass ratio as possible, in order to squeeze the most velocity change available from their nitric acid and hydrazine- especially considering, again, the low total impulse of these fuels.

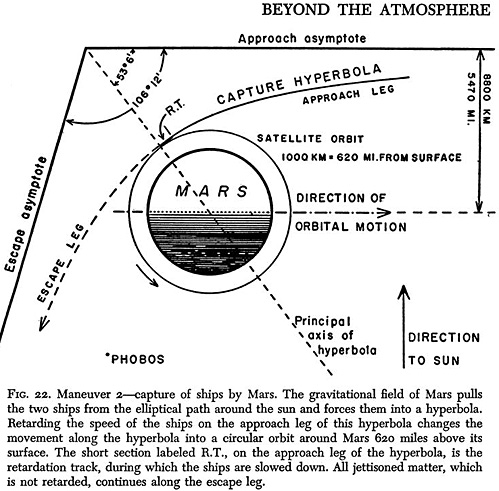

Then, 64 minutes before the retardation power maneuver, the distance of the ships from the center of the planet is only 8,500 miles. Mars is has actually been overtaking the ships- but for quite some time now, as the ships have been approaching Mars, the planet's gravity has been influencing the ships' speed and location in space very significantly, and is speeding them up and pulling them inwards; nevertheless, the ships, even should they fail to execute the powered retardation maneuver, would not fall onto the surface of Mars, but only sweep through the vertex of their hyperbolic approach to Mars and slip out into deep space again. They have faith, however, in their thoroughly tested rocket engines and know that they will start at exactly the correct moment, and run for the correct length of time.

Illustration from: "Rockets, Jets, Guided Missiles and Space Ships" by Jack Coggins and Fletcher Pratt (Random House: New York, 1951)

Illustration from: "Rockets, Jets, Guided Missiles and Space Ships" by Jack Coggins and Fletcher Pratt (Random House: New York, 1951)

All of the propellant contained in the four remaining external, cylindrical fuel tanks of both ships will be used up during the retardation power maneuver (two of the tanks for the deep space ship have already been drained and discarded). The ships are only about 64 minutes away from ignition of the engines for the power maneuver and have already been attitude positioned for this maneuver.

When the engines begin their run the acceleration is only one third G. Only six of the original rocket engines for each ship make the run; the other six engines (rigid, non gimballing engines) do not run, but rather, have been disconnected, and slip loose from their moorings at the moment of ignition of the remaining engines. The discarded engines will continue to sweep along the hyperbolic capture maneuver track and escape from Mars, sweeping out into space again, never to return, but rather circle the sun in an eccentric orbit. Jettisoning six of the engines helps bring the mass ratio of the ships back up again to a more nearly ideal figure, again, helping to conserve fuel. Why not just throttle back all the remaining engines, instead of jettisoning six of them? Because, the engines must never be allowed to operate at a fractional rate of fuel consumption; this will result in a reduction of the velocity of their exhaust, something that is forbidden.

The six engines run for a grand total of 530 seconds: almost nine minutes! All of this for only a modest reduction in velocity; the ships will have slowed down from 3.2 miles per second to 1.95 seconds- the engines will shut off at an altitude of 620 miles above Mars- the precisely desired altitude for their circular orbit above Mars, as originally planned for the expedition.

After preliminary housekeeping operations the men will make a very thorough survey of the surface of Mars with the deep space ship's telescopes. It is right here where they will probably set the stage for the catastrophic disaster that would very likely befall the expedition.

With the next installment we will discuss the weakest links in the planning of the expedition, and how these mistakes in planning and the conclusions and decisions made by the crew at Mars as a result of their surface survey would have likely caused the destruction of the landing craft in its attempt to land on Mars.

We will also point out the design faults in the landing craft/ascent stage as it is depicted in the illustrations. The design flaws would almost certainly not have actually been incorporated into the design of the landing craft; the aeronautical engineers would almost certainly have known how to get the design of the landing craft right; it is only the popular depiction of its design in the illustrations that is faulty.

The 1956 Mars Expedition Proposed by Von Braun and Ley

- Part 1: Mission Introduction

Part 1: Mars Departure: 10,075 Miles Above Earth

Part 1: Power Maneuver for Martian Orbit

Back to Table of Contents -- Aerospace History and Technology # 3

Back to Aerospace History and Technology List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Lt. Col. William J. Welker, USAF (ret)

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com