The Action Begins

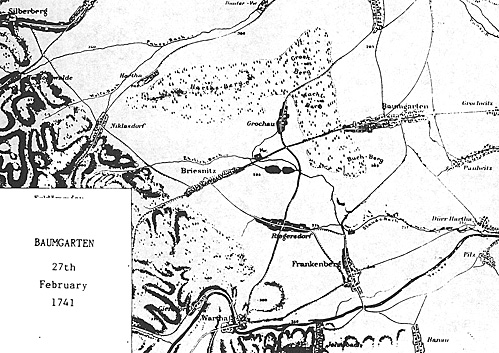

That morning, Frederick left Frankenstein where he had arrived just after the departure of the Austrians. Accompanied only by a squadron of Horse Grenadier Regiment von de Schulenburg (DR3), he rode southwest to visit the two companies of Infantry Regiment von Derschau (IR 18) posted at Silberberg. His escort then returned to Frankenstein and was replaced by another of the same regiment under Lt. Colonel von Diersfort. Frederick then continued his tour by riding southeast to the village of Frankenberg where his elite bodyguard Gensdarmes Squadron (CR11) under Lt. Colonel von der Asseburg was expected. The king now only had the post at Wartha to inspect before returning to Frankenstein and continuing his journey to see Schwerin.

Diersfort was sent back to Baumgarten on the Wartha-Frankenstein road to secure the way back. Asseburg and half of his squadron remained at Frankenberg, while Frederick and the remainder pushed on to Wartha itself. There he made a few adjustments to the deployment of the outpost: an additional company of Derschau Infantry (only 50 strong) and forty hussars [2].

He had been there barely fifteen minutes when an urgent message arrived from Asseberg that a party of enemy hussars had appeared from the mountains by Briesnitz and were riding hard for Baumgarten and Frankenberg. Realizing the danger, Frederick hurriedly set out with the entire force at his disposal. Then more Austrians suddenly appeared close by. Shots rang out from the houses across the river at Johnsbach. This was Trips' party. The net was closing.

The Prussian hussars were left to drive off their Austrian counterparts, while the rest of the party hurried on to the relative safety of Frankenberg. From there, Frederick sent his Aide-de -Camp, Count Wartensleben, to Diersdorf who was at Baumgarten, instructing him to join them so that the whole force could cut its way out.

Diersdorfs squadron (6 officers and 73 men) set out along the road to Frankenberg. They considered themselves members of an elite unit that dated back to 1704. They were distinguished from the ordinary dragoons by their title, Grenadiere zu Pferde , and their muchprized black leather fusilier-style hats which bore the cross of the prestigious Black Eagle Order on their polished copper front plates. Resplendent in their white coats trimmed with red, they rode unsuspectingly through the snow-covered landscape.

Suddenly, the Austrians burst out from the hills and swooped down the slope towards them. Wild cries and pistol shots filled the air. Unused to this style of fighting, the Prussians were taken by surprise and thrown into confusion. Hastilly, the riders turned their horses and sped back towards Baumgarten. The swifter mounts of their opponents soon closed the gap. Then, to the Prussians' horror, they discovered a marshy ditch to their front. Horses stumbled and riders were thrown and the Austrians closed in for the kill. The remaining riders desperately jumped the ditch and fled towards Frankenstein. Encumbered by the flag, the squadron standard bearer stumbled and fell into the ditch, leaving the brilliant, gold embroidered banner as a trophy to the enemy [3]. Frederick learned of the disaster from Wartensleben, who had hastened back to Frankenberg. Immediately, he set out for Baumgarten before that road could be completely blocked. Fortunately, that village was now securely held by six companies of Infantry Regiment von Jeetze (IR 30 with 300 men) who had hurried up from Frankenstein. Diersfort was also busily reforming his squadron nearby, while the Austrians had disappeared.

Frederick had had a narrow escape and he knew it. The experience left him considerably rattled and irritated at his own lack of caution. He vented his feelings on poor General Schulenburg, the elderly colonel of the Horse Grenadiers, who was severely chastized for his men's poor performance, despite being miles away at the time. Efforts were made to prevent the news of the rout leaking out to the public. General Derschau was ordered to begin an investigation, and a new standard was made " so that this does not give people a chance to gossip " [4]. The unfortunate Horse Grenadiers went on to compound their poor performance by routing at Mollwitz six weeks later, for which they were deprived of their distinctive headgear and relagated to dragoon status.

Meanwhile, Frederick extracted maximum propaganda value from the affair which Prussian ministers portrayed as a dastardly plot and further evidence of Austrian perfidy. Secretly, however, instructions were sent to Minister Podewils, in charge of Prussian civil government, for the event of a similar Austrian attempt being more successful in the future. In particular, Podewils was ordered not to make any dangerous concessions to secure the king's release, but to prosecute the war with even greater vigour.

Comments

The Prussian monarch had been very lucky indeed. Not only did he escape capture at Frankenstein on the 26th and at Baumgarten, but he also missed the Austrians as he rode through Briesnitz early on the 27th. Briesnitz was the rendevous of the two Austrian hussar detachments sent by Trips to cut the Wartha-Frankenstein road. As he passed through Briesnitz, the king was only accompanied by Diersfort's squadron of Horse Grenadiers, who would have been out-numbered two-to one by the Austrians.

Furthermore, if Trips' own party at Johnsbach had been larger, Frederick would have had more trouble escaping from Wartha to Frankenberg. Frederick's official bodyguard, Asseburg's squadron of Gensdarmes, had a paper strength of 148, but was probably below 100 men, and the king had only half of those with him at Wartha. With the 50 Derschau infantry and 40 hussars, he probably had no more than 140 men with him when Trips' thirty troopers opened fire.

Dierfort's squadron was routed by the first of the two Austrian detachments from Briesnitz. This totalled seven officers and 60 men and was led by Rittmeister Komaromy, who had mistaken the Horse Grenadiers for the royal escort. Although he had attacked the wrong troops, Komaromy's rout of Dierfort's squadron left Frederick with only the 190 men at Frankenberg. The nearest other Prussian troops were the 300 Jeetze Infantry who were still over 5 km away on the other side of Baumgarten. Luckily for Frederick, the second Austrian detachment never made an attack. Yet the king did not know this at the time, and, more to the point, had no idea how many more Austrians might be lurking about in the hills and villages between him and safety.

Notes

[1] Count Friedrich Heinrich von Seckendorff (1673-1763). Seckendorff had been ambassador to Prussia between 1726 and 1737. He had a high military reputation, though the beginning of 1740 found him in prison following the Austrian defeat by the Turks for which the Viennese court held him responsible. Freed by the new Queen Maria Theresa, Seckendorff rather ingraciously resigned his post after Mollwitz and joined her enemies as commander-in-chief of the Bavarian forces.

[2] Almost certainly from the Leibkorps Husaren (later HR2).

[3] This clash cost the Horse Grenadiers 11 dead, 8 wounded, including one officer, and 16 captured. In addition to their standard, they lost their pair of kettledrums and 35 horses. The Austrians lost 4 killed and 5 wounded.

[4] Quoted in the Generalstabwerk, 1320. Nothing is known of the outcome of the investigation.

Bibliography

Prussian General Staff, Der Erste Schlesische Krieg 1740-42 , (3 volumes, Berlin, 1890-93, vol. 1, esp. pp. 313-320.

C. von Jany, Geschichte der Koniglich Preussischen Armee,(4 volumes, Berlin, 1928-29) vols. I & II.

R.B. Asprey, Frederick the Great: The Magnificant Enigma, (New York, 1986).

Alte Fritz's Narrow Escape At Baumgarten February 27, 1741

- Introduction

The Action Begins

Appendix: Position of the Opposing Forces on February 20, 1741

Jumbo Baumgarten Map (very slow: 237K)

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VIII No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1996 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com