Of Hochkirch and Rex Pils

Frederick had been the agressor in 1756 with the invasion of Saxony, and in 1757 in Bohemia, but in 1758 it was the Austrians who were on the strategic offensive, trying to wrest Saxony away from the "Bad Guys", i.e. the Prussians, (Professor Duffy maintains that throughout history, the bad guys generally wore blue uniforms while the good guys wore white. Draw your own conclusions here.) The 1758 campaign would culminate in the battle of Hochkirch, which was one of Frederick's worst military defeats.

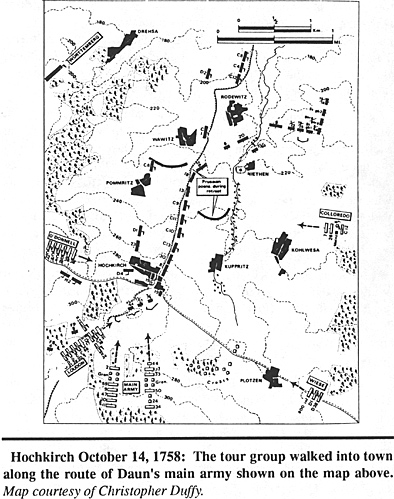

Hochkirch October 14, 1758: The tour group walked into town along the route of Daun's main army shown on the map above. Map courtesy of Christopher Duffy.

Essentially, the Prussians were strung out in a large camp and were outnumbered by the Austrians by a factor of three to one. Here, the Austrian general Daun conceived a new tactic: his forces would form into large attack columns (brigade or division strength) and converge on Frederick's position from every possible angle. Daun realized that Austria's superiority in manpower was not put to good use when the army deployed into long, clumsy linear battle lines that might stretch four or five miles in length. Frederick could mount a local attack with all of his strength and defeat the opponent before the rest of the Austrian army could move and get into action. However, by dividing his army into smaller task forces, he could manouver around and behind the Prussians and overwhelm them. The tactics of Hochkirch could negate the tactics of Leuthen. Hochkirch was the first test of this tactic of converging columns and it proved to be highly effective.

Again, the weather cooperated with us as we traveled to Hochkirch via Bautzen, a Napoleonic battlefield. We also passed the Moritzburg Castle, a famous hunting lodge placed on an island in the middle of a lake. The castle was owned by Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau ("the Old Dessauer"). Professor Duffy delighted us with some humorous stories about the Old Dessauer, particularly with his experiment in raising childeren. One child, Prince Moritz, was not taught to speak, read, or write because the Old Dessauer wanted to see how much the lad could learn on his own.

Meanwhile, near Hochkirch, we departed our bus at the town of Wuischke and followed on foot the line of the main Austrian attack from that village to Hochkirch. A series of wooded areas and ridge lines shielded us from the village of Hochkirch, so one can imagine how easy it was for the Austrians to sneak up on the Prussians and overwhelm them.

Professor Duffy courageously led the assault of the Good Guys into Hochkirch, and we stormed the town with nary a casualty. As the only Prusso-phile I was sorely tempted to sprint ahead of the pack and warn the Bad Guys of the pending attack. Alas, I was much too busy loading and shooting my camera at the double quick; it seems as if I am always at the end of a roll of film whenever we are about to approach a new battle site.

The town of Hochkirch is particularly interesting because a majority of its buildings date back to 1758 and before. Substitute dirt roads for the modern-day asphalt and you can get a fairly good idea of what a Saxon town might have looked like in the 18th Century.

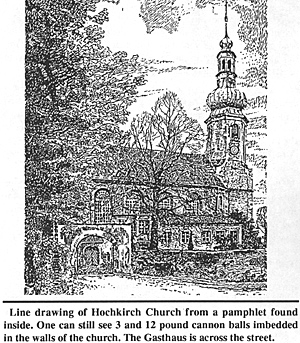

Line drawing of Hochkirch Church from a pamphlet found inside. One can still see 3 and 12 pound cannon balls imbedded in the walls of the church. The Gasthaus is across the street.

Line drawing of Hochkirch Church from a pamphlet found inside. One can still see 3 and 12 pound cannon balls imbedded in the walls of the church. The Gasthaus is across the street.

We ate our lunch at the Gasthaus Alte Fritz , just a few steps from the famous churchyard and the Blutgasse (trans. blood alley). I ate a hearty meal of Weiner Schnitzel and pommes frites, washed down by a few glasses of Rex Pils beer. The Rex Pils bottles have a picture of Frederick the Great on the label as do the Rex Pils beer glasses and beer mats. I offered to purchase one from the owner, but he declined, saying that he only had a few glasses; however, he did allow me to keep one of the bottles and to take a couple of beer mats bearing Alte Fritz's face.

After lunch we all took turns posing in front of Hochkirch Church with a life-sized cardboard soldier that the tavern owner had acquired as a promotional aid for the beer. I managed to snap a picture of Professor Duffy standing next to the mannequin. He held one hand above the figure with the old Roman "thumbs down" gesture, so I snuck up behind him and gave ye olde "thumbs up" signal in the interests of fairness and equal time for the Prussians. What fun!

Hochkirch was the most enjoyable site of the tour for me, even though my hero, Frederick, took a good beating there. Perhaps the combination of the nice weather, the morning walk into the town, a well-preserved and pristine battle site, and lunch at the Alte Fritz Gasthaus were enough to make me overcome my grief for this Prussian defeat. Then again, maybe a few glasses of Rex Pils had something to do with it.

Following our visit to Hochkirch, we stopped in Dresden to see the Saxon Army Museum. I mention this because the museum contains some excellent examples of Prussian SYW-era miter caps, uniforms and small arms; plus a nice collection of 1806-era Prussian uniforms (another favorite period of mine). The museum also contains numerous diaramas using zinnfiguren flats that depict a complete Prussian regiment of two battalions (10 companies) at a 2:1 figure scale. It is very impressive to see so many miniatures representing a single regiment. One display depicted two battalions marching in column, while another had them deployed in a battle line, complete with regimental guns and file closers, about to receive a charge from a regiment of Austrian cuirassiers and a regiment of Saxon cheveau-legers. Now I've long been an advocate of large scale wargame units (i.e. 20 to 40 figures), but I believe that even those who prefer much smaller units would have to admit that these displays were a visual spectacle that would be hard to beat.

Maxen and Freiburg

This was to be our last extensive day of battlefield tours. It was interesting in that each winner employed Daun's tactics of converging columns instead of the more traditional linear tactics. Freiburg was fought between Prince Henry's Prussian army and the Reicharmee ( a collection of German states under the auspices of the Holy Roman Empire, plus a stiffening force of Austrians). Freiburg was an important crossroads town in Saxony in that every important road in Saxony eventually ran through the town. Prince Henry had lost it to the Reicharmee in 1763 and he was detrmined to win it back.

The rough, wooded terrain and hills that concealed the approach marches made Daun's converging columns tactic ideal for the occaision, and Prince Henry was not loath to borrow a good idea. Henry's attack succeeded and Freiburg returned to Prussian hands. Even more importantly, the Austrians realized that they could not evict the Prussians from Saxony in 1763, so, tired of war, they agreed to go to the peace table. Freiburg does not offer a visually appealing battle site in that much of the ground has been consumed by urban sprawl; accordingly, we did not spend much time there.

Maxen, on the other hand, is in an isolated area southeast of Dresden and is very well preserved. Here, Daun trapped a detached corps of 15,000 Prussians under the command of General Fincke, who was forced to surrender after a short, but disgraceful fight in which the majority of Prussians chose to run rather than fight. Frederick never forgave Fincke for losing so many men and forever contemptuously referred to all Prussian foot and cavalry units involved as "those Maxen regiments". Again Daun used the converging attack columns to great effect.

The battle had three distinct phases. The first was a long-range cannonade of fifty Austrian guns versus eleven Prussian guns, in front of the town of Maxen. An Austrian attack and the fight inside the town marked the second phase of the battle, and finally, there was a cavalry action on the far side of the town.

I was particularly impressed by the strong defensive position that Maxen affored the Prussians. The town is situated on top of a hill, with a deep ravine between it and the Austrian position on a facing hill. A narrow ridge or causeway connects the two positions. The battle was fought in the winter, so the slopes in front of the Prussian lines were treacherous and slippery. It looked like a very good position.

Daun occupied two hills facing Maxen and proceeded to open up a long-range artillery bombardment on the Prussian infantry deployed in front of the town. I cannot begin to guess the range between the respective lines and batteries, but I would have guessed that the Prussians were out of range. Au contraire! Not only were they within range, but the overshots landed among a second line of hussars and dragoons, scattering them. Austrian artillery rounds even flew over the town and into the Prussian baggage train, with good effect.

I had always been under the impression that long-range artillery bombardment was discouraged during the 18th Century, but the results of Maxen seem to defy the conventional wisdom. Likewise, there is evidence of long-range artillery fire at Kolin and Lobositz.

Torgau - A Prussian Victory?

Professor Duffy finally allowed us to visit the site of a Frederician victory; however, after walking the field of Torgau, I was left with the impression that Frederick was perhaps more lucky than he was great .

Torgau guarded one of the Elbe River crossings in Northern Saxony and the low ridge to the west of the town provided one of the last defensible pieces of ground between Saxony and Berlin. The rolling hills of Saxony flatten out into the great north German plain, which stretches across northern Europe from the North Sea to the Ukraine. Beyond Torgau, the terrain is flat, flatter and more flat.

In 1762 the Austrian general Daun occupied the Torgau plateau and Frederick resolved to attack him. In typical Frederician fashion, Alte Fritz conducted a grueling march around the flank and rear of the Austrian position, only to find that the enemy was in a stronger position than anticipated. Frederick seems again and again to run into this problem of exhausting his men with a hard march around the flank of the enemy only to find that the new point of attack is directed towards a defensive position that is stronger than the one he faced prior to the march. He attacks anyway and his tired men get slaughtered.

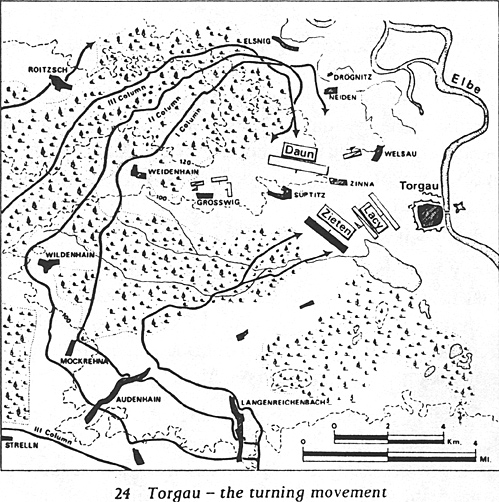

To compound the problem, Alte Fritz had divided his forces into two parts. The King commanded the main army while his lieutenant, General von Zieten, took the other half. Zieten presumably had orders to attack the Torgau plateau from the south while Frederick attacked from the north. His plan for Torgau was sort of an 18th Century version of Chancel lorsville (1863), only imagine what would have happened to Lee had not Jackson launched his attack. This gives you a general appreciation of what happened at Torgau.

Professor Duffy explained how the Torgau plateau determined the events of the battle. Apparently, sounds originating from south of the plateau, near Suptitz village and the fish ponds, are amplified and are easily heard by anyone standing on the north side of the plateau. Conversely, noises eminating north of the plateau are muffled and can not be heard by anyone standing near Suptitz on the south side.

24 Torgau - the turning movement

24 Torgau - the turning movement

So along come Fritz with his half of the army on the north side of the ridge. They are exhausted from a long night march around the flank of the Austrian army and they have had to literally chop their way through a thick woods to get there. They emerge from the woods only to find that the Torgau plateau is packed full of Austrian white coats and their deadly 12 pound cannons. Frederick hears the amplified sound of an artillery duel coming from the vicinity of Suptitz, south of the plateau, and he assumes that Zieten has attacked the Austrian positions prematurely. Zieten must be saved!

The Prussians emerged from the woods in columns and Frederick threw the ten leading grenadier battalions against Daun's fortified position. Two-thirds of the attackers were cut down within thirty minutes, primarily from Austrian cannon fire. Frederick and his subordinate, von Hulsen, hurl anther sixteen battalions against the Austrians in a second attack, with similar results. A third attack, this time with Holstein-Gottorp's cavalry, gains a foothold on the plateau, but they are forced back when O'Donnell Austrian cavalry counterattacks.

Frederick is lightly grazed by a spent musket ball, and he retires to the nearby village of Elsnig to cry and pout. [Haven't we seen this before?]. Fritz believes that the battle is lost as dusk sets in. Marshal Daun likewise believes that he has won a great victory over the Prussians, and since it is dark, he believes the fighting to be over. He sends a messenger off to Vienna to deliver the good news. Daun then retires to his quarters to tend to his wounded leg. He has no idea what has happened to Frederick.

To this day nobody knows what happened to Zieten, nor do we know what his orders were. He was engaged in heavy fighting at Suptitz, south of the Torgau plateau. All efforts to break into the Austrian rear have failed and Zieten considers calling off his attack, unaware of what has happened to Frederick.

Then a Prussian lieutenant reports that he has found a causeway across the fish ponds, that, until now, have barred Zieten's way. His brigadiers urge Zieten on to one more attack, and in the darkness they fall upon the rear of the Austrian position astride the Torgau plateau. Simultaneously, Hulsen gathers up 1,000 stragglers and two reserve regiments and makes one final push from the north.

There is much confusion in the Austrian camp and many are taken prisoner. Daun is still in Torgau resting from his wounds when he hears the disasterous news. He cannot believe it, but Lacy and O'Donnell confirm all. The order to retreat is given to the Austrians, who file across the Elbe at Torgau. In one final bit of drama, Daun sends another courrier off to Vienna to try and catch up with the first messenger before he can give the false news to the empress in Vienna. My recollection is that he slapped leather for several days on end, and just missed catching up with the first messenger.

It was a costly battle for both sides, with the Prussians losing over 16,000 killed and wounded; while the Austrians lost 7,000 killed and wounded plus 9,000 prisoners. The results were indecisive for both sides in that no strategic advantage was gained by either belligerent.

Today, one can still find the Torgau plateau and the Suptitz causeway and fish ponds. There are signs of a former Soviet military base on the plateau, but it has now been abandoned. Professor Duffy affirmed that it had been a "beehive of activity" only two years before and that prior to the trip, he was not sure if we would be allowed to visit the site: "If we see lines of bullets splashing before us then we know that we have made a terrible mistake, " said Duffy, when asked if we could climb up to the top of the plateau.

Afterwords, we visited the church at Elsnig to see where Frederick hid during the battle. Again it occurred to me that Alte Fritz had his bacon saved by one of his subordinates at the last minute.

The Last Day

This was the last day of the tour for many people, though most remained in Potsdam on Sunday for a tour of Frederick's palace of Sans Souci. Saturday night a raiding party of fifteen SYW enthusiasts infiltrated Berlin and sacked the Zinnfiguren store with a vengeance. It was a literary feeding frenzy as people dashed from one aisle to the next with piles of books in their hands. I was able to restrain myself on book purchases, but I could not pass up the opportunity to buy a reproduction Prussian Guard flag (IR 6) and a brass flag finial for a rediculous sum of money. Herr Bookmeister was undoubtedly pleased with the evening's business and he supplied us with free beer and/or Coca Cola as a gesture of appreciation.

Later that evening, after returning to the hotel in Potsdam from the book raid, I ordered up one last glass of pilsener at the bar. The barkeeper drew a long foamy glass of Rex Pils , slapped a beer mat in front of me, and gently set the glass with Alte Fritz's face on it before me. I looked back on the week's travels, on the places I had seen, the friends I had made, and concluded that the Duffy Tour was well worth it at any price. Then I picked up my glass of Rex Pils, saluted the picture of Alte Fritz and exclaimed, "HERE'S TO THE BAD GUYS!"

Following In The Footsteps of Alte Fritz

- Tour Introduction

The Tour Begins

Battles: Lobositz, Meissen, and Others

Battles: Hochkirch, Torgau, and Last Day

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VIII No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com